10 Liquid injectable silicone

Summary and Key Features

• Two forms of highly purified injectable liquid silicone (Silikon-1000 and Adatosil-5000) are FDA-approved for intraocular tamponade of retinal detachment.

• Both products may be legally injected off-label for skin augmentation, according to the 1997 FDA Modernization Act

• Industrial liquid silicone, including ‘medical grade’ industrial liquid silicone, may contain contaminants that cause granulomatous reactions

• Industrial grade liquid silicone should never be injected into the human body

• Three rules should always be followed when using liquid injectable silicone for skin augmentation, as follows.

• Rule 1: Inject only FDA-approved highly purified liquid silicone

• Rule 2: Employ only microdroplet technique

• Rule 3: Inject limited amounts of volume at monthly intervals or longer

• There is much evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of liquid injectable silicone for HIV-associated lipoatrophy

• With proper protocol, serious adverse events are rare and are usually treatable

Indications and patient selection

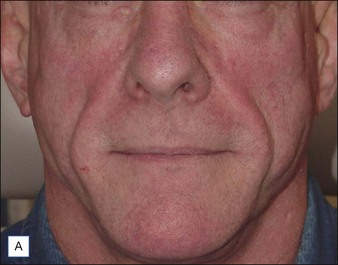

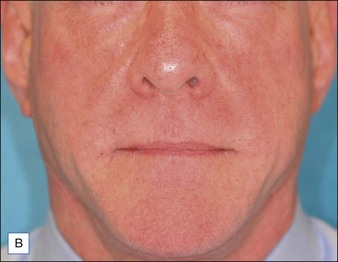

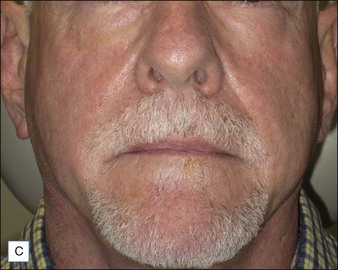

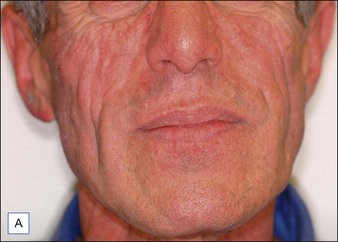

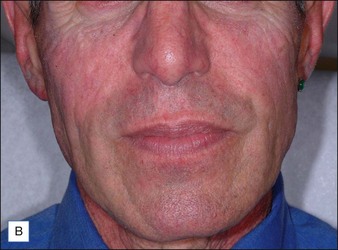

Although there are currently no FDA-approved cosmetic indications for HPLIS, it may be legally injected off-label for the augmentation of HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy, nasolabial folds, labiomental folds, mid-malar depressions, lip atrophy, hemifacial atrophy, acne scarring, other atrophic scarring, age-related atrophy of the hands, corns and calluses of the feet, and healed diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers (see the studies by Orentreich, Balkin, and Fulton et al) (Figs 10.1–10.4). HPLIS is specifically contraindicated for injection into the breast, eyelids, or bound-down scars or injection into an actively inflamed site. Its safety has not been studied in pregnant women. It should not be injected into patients with chronic bacterial sinusitis, dental caries, other active bacterial infection, or in those who may be predisposed to trauma in the treated area. Additionally, HPLIS is not a substitute for surgical lifting, chemical or laser resurfacing, dermabrasion, or treatment of dynamic rhytides with botulinum toxin. The ideal patient is one with appropriate insight into the permanent and off-label nature of LIS, a realistic attitude regarding achievable results, in good physical health, and compliant with recommendations. Patients seeking immediate correction or temporary augmentation should be treated with temporary fillers. Serious consideration by both the patient and physician must be given to the longevity of results obtained with HPLIS. Although permanent fillers may be preferred to temporary fillers owing to their longevity, one must consider the possibility that personal and societal aesthetic goals may change over time. Furthermore, an undesirable result will be unlikely to diminish with time and may be difficult to correct.

Materials

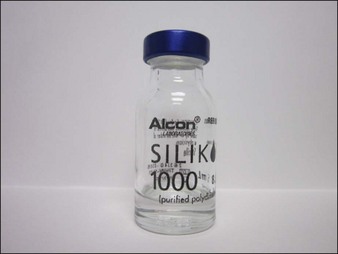

The most appropriate HPLIS for off-label soft tissue augmentation is Silikon-1000 (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) (Fig. 10.5); 5000 cs Adatosil (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY) may also be used off-label, but is too viscous to inject through small-gauge needles. A 0.5 mL of LIS is drawn through a 16-gauge Nokor needle into a 1 mL Becton Dickinson (BD) Luer-Lok® syringe (Fig. 10.6) using sterile technique. As molecules from the rubber stopper of the syringe could theoretically contaminate the HPLIS after a long exposure period, it should be drawn into the injecting syringe immediately prior to treatment, and should never be stored in the syringe. HPLIS is most easily injected through a 27-gauge 0.5-inch (6 mm) Kendall Monoject aluminum-hubbed needle. Plastic-hubbed needles tend to pop off with the higher injection pressures needed for injection through smaller gauge needles. To increase injector comfort, 0.5-inch inner diameter rubber electrical bushings purchased from a hardware store may be autoclaved and placed over the barrel of the syringe to cushion the physician’s second and third fingers during injection.

Patient preparation

Pearl 4

Areas to be treated should be carefully marked pre-treatment using a fine tipped marking pen

appearance when the patient smiles. A topical anesthetic such as lidocaine or other topical amide mixture is then placed on the treatment area and wiped off after 30 minutes with clean gauze.

Side effects and managing complications

al. Ultimately, however, granulomas that fail to resolve may require surgical removal.

Balkin SW. Injectable silicone and the foot: a 41-year clinical and histologic history. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(11 pt 2):1555–1559.

Barnett JG, Barnett CR. Treatment of acne scars with liquid silicone injections: 30-year perspective. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(11 Pt 2):1542–1549.

Baselga E, Pujol R. Indurated plaques and persistent ulcers in an HIV-1 seropositive man. Archives of Dermatology. 1994;130(6):785–789.

Baumann LS, Halem ML. Lip silicone granulomatous foreign body reaction treated with aldara (imiquimod 5%). Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29:429–432.

Benedetto AV, Lewis AT. Injecting 1000 centistoke liquid silicone with ease and precision. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29(3):211–214.

Christensen L. Normal and pathologic tissue reactions to soft tissue gel fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:S168–S175.

Delage C, Shane JJ, Johnson FB. Mammary silicone granuloma: migration of silicone fluid to abdominal wall and inguinal region. Archives of Dermatology. 1973;108(1):105–107.

Desai AM, Browning J, Rosen T. Etanercept therapy for silicone granuloma. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2006;5(9):894–896.

Diamond B, Hulka B, Kerkvliet N, et al. Summary of report of National Science Panel: silicone breast implants in relation to connective tissue diseases and immunologic dysfunction. Online. Available http://www.fjc.gov/BREIMLIT/SCIENCE/summary.htm, 1998. 31 January 2009

Duffy DM. Tissue injectable liquid silicone: new perspectives. In: Klein AW, ed. Augmentation in clinical practice: procedures and techniques. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1998:237–263.

Duffy DM. The silicone conundrum: a battle of anecdotes. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28:590.

Duffy DM. Liquid silicone for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(11 Pt 2):1530–1541.

Duffy DM. Liquid silicone for soft tissue augmentation: histological, clinical, and molecular perspectives. In: Klein A, ed. Tissue augmentation in clinical practice. 2nd edn. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006:141–237.

Fulton JE, Jr., Porumb S, Caruso JC, et al. Lip augmentation with liquid silicone. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(11 pt 2):1577–1586.

Hevia O. Six-year experience using 1,000-centistoke silicone oil in 916 patients for soft-tissue augmentation in a private practice setting. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35:1646–1652.

Jones DH. Injectable silicone for facial lipoatrophy. Cosmetic Dermatology. 2002;15:13–15.

Jones D. HIV facial lipoatrophy: causes and treatment options. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(11 pt 2):1519–1529.

Jones D. Semi-permanent and permanent injectable fillers. Dermatologic Clinics. 2009;27(4):433–444.

Jones D. A report of 135 patients with 5 year and beyond follow up after treatment with highly purified liquid injectable silicone (LIS) for HIV associated facial lipoatrophy (HIV FLA). Chicago, IL: American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Annual Meeting; 2010. 24 October

Jones DH, Carruthers A, Orentreich D, et al. Highly purified 1000-cSt silicone oil for treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-associated facial lipoatrophy: an open pilot trial. Dermatologic Surgery. 2004;30:1279–1286.

Lloret P, Espana A, Leache A, et al. Successful treatment of granulomatous reactions secondary to injection of esthetic implants. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(4):486–490.

Orentreich DS. Liquid injectable silicone: techniques for soft tissue augmentation. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 2000;27:595–612.

Orentreich DS, Jones DH. Liquid injectable silicone. In: Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Soft tissue augmentation. New York: Elsevier; 2006:77–91.

Orentreich D, Leone AS. A case of HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy treated with 1000-cs liquid injectable silicone. Dermatologic Surgery. 2004;30:548–551.

Parel JM. Silicone oils: physiochemical properties. In: Glaser BM, Michels RG, eds. Retina, vol 3. St Louis: Mosby; 1989:261–277.

Pasternack FR, Fox LP, Engler DE. Silicone granulomas treated with etanercept. Archives of Dermatology. 2005;141(1):13–15.

Price EA, Schueler H, Perper JA. Massive systemic silicone embolism: a case report and review of literature. American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 2006;27(2):97–102.

Rapaport MR. Silicone injections revisited. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28:594–595.

Rapaport MJ, Vinnik C, Zarem H. Injectable silicone: cause of facial nodules, cellulitis, ulceration, and migration. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 1996;20:267–276.

Selmanowitz VJ, Orentreich N. Medical grade fluid silicone: a monographic review. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1977;3:597–611.

Spanoudis S, Koski G. Sci.polymers. Online. Available http://www.plasnet.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=89:polymer-faq&catid=118:FAQ&Itemid=258, 2009. 31 January 2009

Turekian KK, Wedepohl KH. Distribution of the elements in some major units of the earth’s crust. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. 1961;72(2):175–192.

Wallace WD, Balkin SW, Kaplan L, et al. The histological host response of liquid silicone injections for prevention of pressure-related ulcers of the foot: a 38-year study. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2004;94:550–557.