Chapter 31 Liposuction of the abdomen and trunk

• Liposuction is one of the most common esthetic procedures performed and the incidence of complications is low.

• Liposuction is more of an art than a surgical procedure.

• Liposuction entails a practical application of scientific knowledge with precision and craftsmanship and is a skill attained with clinical experience.

• In this chapter the technique, the pearls and the pitfalls of liposuction are described in detail. A series of patients who underwent liposuction of abdomen and trunk are presented.

• The long-term results of liposuction depend on the preoperative condition of the patient’s skin, the patient’s overall health and expectations, and the ability of the patient to maintain a healthy weight and lifestyle postoperatively.

Introduction

Concepts of beauty have been continuously evolving throughout the history of mankind. The voluptuous figures that were idealized by artists in the past have been substituted by slimmer forms. In many countries, liposuction is the most frequently performed esthetic procedure.1,2 Liposuction has evolved tremendously over the past three decades. Since its introduction, it has progressed into one of the most popular procedures in plastic surgery.3,4 The “Illouz Method” featured a technique of suction-assisted lipolysis after infusing fluid into tissues using blunt cannulas and high-vacuum suction and demonstrated both reproducible good results and low morbidity. Liposuction is more of an art than a surgical procedure. It entails a practical application of scientific knowledge with precision and craftsmanship and is a skill attained with clinical experience. The development of liposuction provided plastic surgeons with a safe and effective way to sculpt the human figure.5 It brings as much contentment and joy to the person undergoing it, as to the surgeon practicing the intimidating task of delivering that eventual result. The goal of liposuction is the reduction of localized fatty tissue to produce well-proportioned body contours. Although liposuction has been considered a safe surgical procedure for the last 30 years, to maximally avoid complications, one should be mindful of all the factors that could predispose to them.6

Preoperative Preparation

• Significant medical conditions that may be aggravated by surgery or anesthesia, and use of all medications, vitamins and herbs must be documented.

• Local conditions of skin or subcutaneous tissue that make liposuction hazardous.

• Psychological contraindications such as mood disorders, thought disorders, severe anxiety, or unrealistic expectations.

Appropriate indications should be recorded in the clinical record which may include:

Surgical Technique

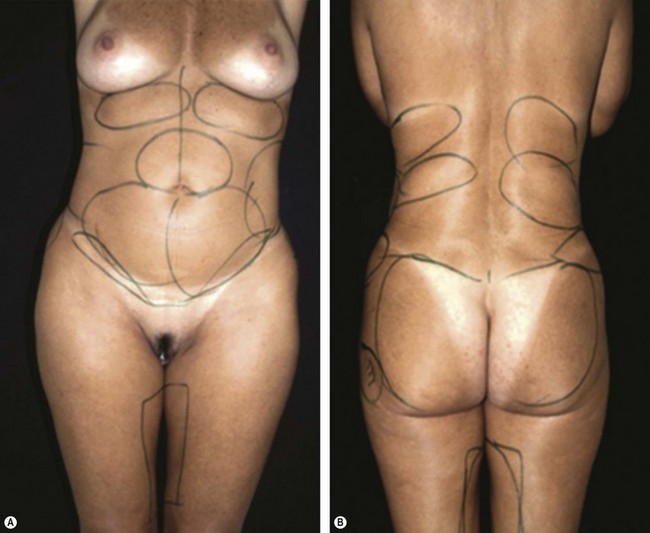

1. Markings of the areas to be liposuctioned and fat grafted are made while the patient is in the standing position (Fig. 31.1A, B).

2. Preoperative sedation in the surgical suite is administered. Anesthesia consists of an epidural block and intravenous sedation. The patient is placed in supine position.

3. After the injection of normal saline wetting solution containing 1 : 500 000 of epinephrine (adrenaline) by a small-bore cannula and waiting 15 minutes, a 60 ml syringe attached to a 4 mm blunt cannula is inserted through two small incisions in the area to be liposuctioned.

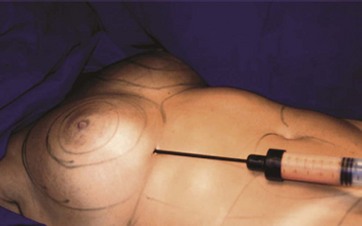

4. Fat is aspirated using the syringe method in the dorsum and the flanks (Fig. 31.2).

5. If autologous fat transfer is being considered, the aspirated fatty tissue is treated in the following manner: With the syringe held vertically with the open end down, the fat and fluid are separated. Isotonic saline is added to the syringe, the fat and saline are separated and the exudate discarded. The procedure is repeated until the fat becomes yellow in color, free of blood and triglyceride oil. Our experience with autologous fat transplantation in treating various tissue defects has been published previously.7–9

6. When gluteal augmentation is scheduled, a deep plane to the gluteal muscles is created by the 4 mm cannula. Then other planes are created by the same cannula in different trajectories, always from the deeper aspect to the gluteal surface. The fat is inserted into these tunnels beginning at the deep layer and working up into the intermediate fat compartments. The fat is injected as the cannula is withdrawn. Care should be taken to avoid injection of more fat in the superficial fat compartment. Separate incisions, if necessary can be used to treat the whole gluteal region (Fig. 31.3).

7. When needed, fat grafting to the female breast (Fig. 31.4) and liposuction to the abdomen is then performed (Fig. 31.5). When indicated, lipoabdominoplasty is performed. The combination of circumferential liposuction, fat grafting of the buttocks and lower limbs, and modified transverse abdominoplasty has been described as composite body contouring in the literature.10

8. The patient remains hospitalized for 24 hours. Antibiotics, analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications are prescribed during the following 7 postoperative days.

A video demonstrating the technique is presented.

Nine illustrative cases are presented.

Case 1

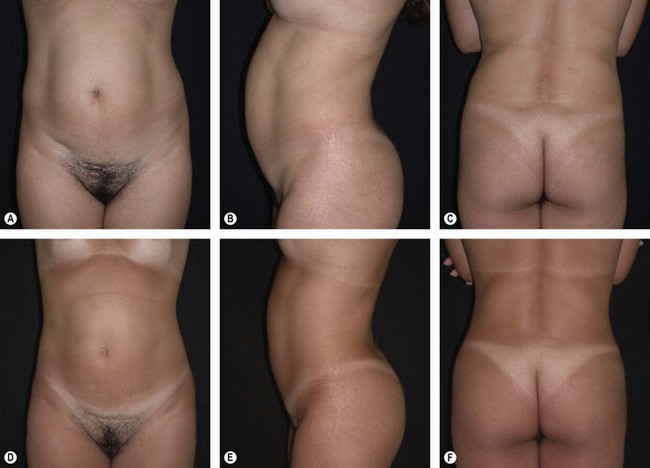

This 24-year-old lady presented complaining of “extra fat” which made her “unattractive” (Fig. 31.6A–C). Liposuction of the back, flanks, and abdomen and autologous gluteal lipograft was performed. Photos were taken 3 years after the procedure (Fig. 31.6D–F). Breast augmentation by silicone implant was also performed.

Case 2

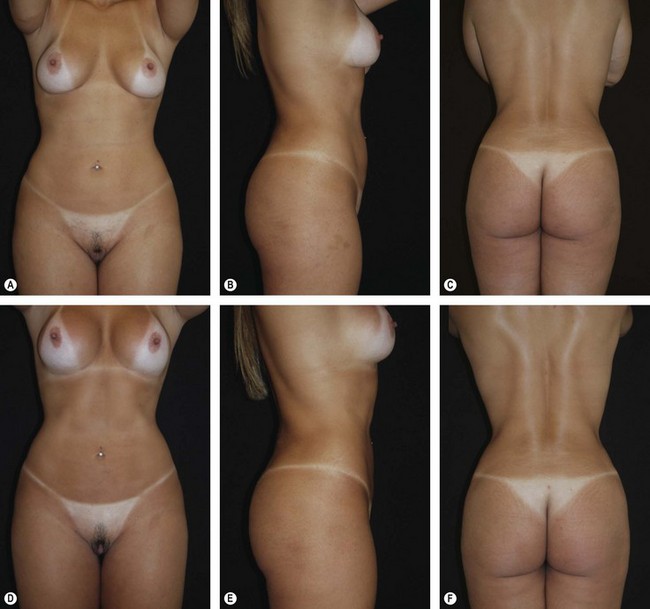

This 41-year-old woman presented for liposuction and moderate buttock enhancement (Fig. 31.7A–C). Liposuction of the back, flanks, and abdomen and autologous gluteal lipograft was performed. Photos were taken 4 years after the procedure (Fig. 31.7D–F).

Case 3

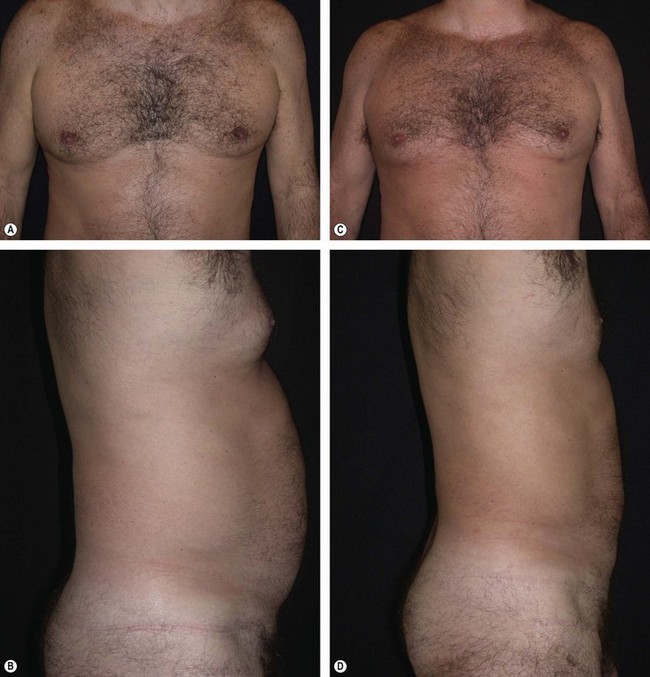

A 40-year-old man requested a better definition of his trunk (Fig. 31.8A–C). He underwent liposuction. Photos were taken 4 years after the procedure (Fig. 31.8D–F).

Optimizing Outcomes

The shape, volume, and size of the body contour vary greatly. These variations can be observed in the same person during his/her lifespan. Ethnic background, sex, genetics, hormones, physical exercise, and diet are some of the factors that influence body contour. True body sculpting demands a three-dimensional understanding of the anatomic and surgical adipose layers of the abdomen and the trunk when performing liposuction.11 Although liposuction is not a technically difficult procedure, it requires thoughtful planning and an artistic eye to achieve esthetically pleasing results.

• Thorough clinical examination should include a detailed evaluation of the regions to be lipocontoured, including a notation of hernias, scars, asymmetries, cellulite, and stretch marks.

• The safety of the liposuction technique relates not only to the amount of tissue removed but to the patient’s overall health. It is ideal for the patient to be as fit as possible before the procedure and not to have smoked for several months.

• Standardized photo documentation is required. Contour lines are drawn about the fat to be extracted and the areas that need to be lipografted.

• Liposuction is performed by three plastic surgeons simultaneously, coordinated by the chief surgeon, with a significant saving of surgical time.

• Appropriate measurements of the extracted fat of each region must be recorded and the contralateral side must be treated in a similar manner.

• In the back all the fibrous bands separating the rolls are aggressively lysed with the Mercedes tip cannula.

• Improvement of the gluteal contour can be attained through augmentation of the gluteal region by means of autologous fat transplantation.

• Fat deposits may extend above the rib margin, and the cannula must be torque to get above the ribs. Using the flat of the hand to press the ribs downward allows free passage of cannulas from several directions. The opposite hand is also needed to judge how much fatty tissue is left in place.

According to a recently published article, there is a growing contingent of nonsurgery trained physicians providing liposuction.12 Physicians practicing liposuction surgery should have adequate training and experience in the field.13,14 This training and experience may be obtained in residency training, cosmetic surgery fellowship training, CME-accredited postgraduate didactic and live surgical programs, or via proctorship with trained credentialed surgeons experienced in liposuction techniques. With the overall acceptance of esthetic surgery increasing, and the number of patients undergoing liposuction increasing, it is likely that plastic surgeons will see more patients requesting secondary liposuction procedures in the future.15 The abdominal area is a difficult region for liposuction and can be responsible for serious local sequelae that are difficult to correct and generally require fat grafts to correct contour issues.16

• The flat-bladed cannula should always be used with the suction hole facing downward and never upwards, in order to prevent contour irregularities.

• One of the most important factors for surgeons to consider when performing liposuction is whether the procedure can be performed during a single surgical session, or whether it will require several sessions. The overall amount of fat removed should not exceed 7% of the total body weight.

• The greater the fibrous content of a fat compartment, the more resistance to penetration by a cannula, and the more difficult it is to achieve a satisfactory degree of liposuction. The use of the smallest diameter cannulas (3 mm) greatly facilitates liposuction in areas that are especially fibrous, such as the midlateral back.

• The skin on the back is especially susceptible to hyperpigmentation of scars from incisions for liposuction. The number of scars should be minimized and care taken to avoid unnecessary trauma to the epidermis near incision sites on the back. Trauma to the dermal-epidermal junction predisposes to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

• Any alteration to the natural look of the gluteal fold may result in a cosmetically disturbing complication. Liposuction corrects the fat bulging, but not the skin laxity. A useful test is done when the patient is lying in the prone position. If the “banana” fold of the infragluteal region disappears, there is excess of skin and lipografting or more complex procedures should be performed. If the “banana” fold continues to be present, there is residual adipose tissue that needs to be corrected by liposuction.

• Irregularities ranging from “oversuctioning” to bumpy skin (Fig. 31.10) and asymmetries result from inadequate experience of the surgeon.17,18

• An overaggressive approach to liposuction of the flanks can injure the subdermal vascular plexus and produce chronic erythema.

• Postoperative fluid collection and hematoma require active intervention by draining of fluid collection using a syringe (Fig. 31.11).

• To enhance patient satisfaction, minor complications related to surgical trauma need to be addressed aggressively.

• No statistical differences in adipocyte viability have been demonstrated among abdominal fat, thigh fat, flank fat, or knee fat donor sites.19 The donor site can be chosen according to the preference of the surgeon and the patient.

• Recent reports have shown that mechanical centrifugation does not appear to enhance immediate fat tissue viability before implantation.20 An important consideration for harvesting and refinement in preparation for grafting is to respect and maintain the tissue architecture of living fat. Any mechanical or chemical insult that damages the fragile tissue architecture of fat will result in eventual necrosis of the injected fat.

• The transplanted fat must have access to blood supply. The creation of multiple tunnels ensures adequate blood supply to the grafted fat. Intramuscular fat grafting should be done in tunnels also and retrograde injection should be performed, in order to avoid intravascular fat injection.

• For predictable results, the surgeon should refine the fat into relatively pure living tissue, using sterile conditions and avoiding external contact, thus preventing contamination. Transplanting a high percentage of nonviable components such as blood and triglyceride oil reduces the potential for accurate volume estimation.21

• Surgeons have come to realize that transplanted fat can create not only satisfying changes in contour, but also long-lasting results.22,23

Lipoaspirate, an otherwise disposable byproduct of cosmetic surgery, has been shown to contain a putative population of stem cells, termed adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) that share many similarities to marrow stromal cells (MSCs) from bone marrow.24 ADSCs reside within the stromal-vascular fraction (SVF) in fat tissue, which is thought to harbor cells that display extensive proliferative capacity and multilineage potential.25 Recently, approaches based on ‘ADSCs enriched lipograft’ have been published.26 ADSCs have a great potential for use in tissue repair and regeneration in the field of plastic and reconstructive surgery. Although the currently applied strategies for adipose tissue engineering have advanced in recent years, complete understanding of the mechanisms of interactions among adipose stem cells, growth factors, and biomaterials in tissue engineering is needed in order to advance the end goal of developing ‘off-the-shelf’ tissue engineering products.

Complications and Their Management

• Edema, ecchymosis, dysesthesia, fatigue, soreness, scarring, asymmetry, and contour imperfections are expected sequelae after liposuction.

• Persistent edema, long-term dysesthesia, hyperpigmentation, pruritus, hematoma and seroma are occasional side effects after liposuction.

• Skin necrosis, severe hematomas, recurrent seromas, nerve damage, systemic infection, hypovolemic shock, intraperitoneal or intrathoracic perforation, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism (ARDS) and loss of life are uncommon sequelae after liposuction.

Although plastic surgeons have developed safety measures to perform the technique, there are serious risks, including death at a rate of 1/5000 procedures. Major surgical complications can be avoided by following well-known safety guidelines.27

1 Sterodimas A, Huanquipaco JC, de Souza Filho S, et al. Autologous fat transplantation for the treatment of Parry-Romberg syndrome. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(11):e424–e426. Epub 2008 Aug 15

2 Haeck PC, Swanson JA, Gutowski KA, et al. Evidence-based patient safety advisory: liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(4 Suppl):28S–44S. Review

3 Pereira LH, Sterodimas A. Treatment of iatrogenic abdominal contour irregularities. Aesth Plast Surg. 2010;34(2):129–135. Epub 2008 Aug 28

4 Jewell ML, Fodor PB, de Souza Pinto EB, et al. Clinical application of VASER–assisted lipoplasty: a pilot clinical study. Aesth Surg J. 2002;22(2):131–146.

5 Triana L, Triana C, Barbato C, et al. Liposuction: 25 years of experience in 26,259 patients using different devices. Aesth Surg J. 2009;29(6):509–512.

6 Pitanguy I. Evaluation of body contouring surgery today: a 30-year perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(4):1499–1514. discussion 1515–26

7 Pereira LH, Radwanski HN. Fat grafting of the buttocks and lower limbs. Aesth Plast Surg. 1996;20(5):409–416.

8 Pereira LH, Sterodimas A. Free fat transplantation for the aesthetic correction of mild pectus excavatum. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32(2):393–396.

9 Haroldo Pereira L, Sterodimas A. Aesthetic restoration of axillary contour deformity after lymph node dissection. J Plast Reconstr Aesth Surg. 2008;61(2):231–232. Epub 2007 Nov 19

10 Pereira LH, Sterodimas A. Composite body contouring. Aesth Plast Surg. 2009;33(4):616–624. Epub 2009 May 12

11 Rohrich RJ, Smith PD, Marcantonio DR, et al. The zones of adherence: role in minimizing and preventing contour deformities in liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(6):1562–1569.

12 Camp MC, Wong WW, Wong RY, et al. Who is providing aesthetic surgery? A detailed examination of the geographic distribution and training backgrounds of cosmetic practitioners in Southern California. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(4):1257–1262.

13 Sterodimas A, Radwanski HN, Pitanguy I. Aesthetic plastic surgery: junior plastic surgeons’ confidence in a training program. Aesth Plast Surg. 2009;33(1):131–132. Epub 2008 Dec 31

14 Sterodimas A, Boriani F, Bogetti P, et al. Junior plastic surgeon’s confidence in aesthetic surgery practice: a comparison of two didactic systems. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(8):1335–1337.

15 Matarasso A, Wallach SG, Rankin M, et al. Secondary abdominal contour surgery: a review of early and late reoperative surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(2):627–632.

16 Illouz YG. Complications of liposuction. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(1):129–163. viii

17 Pereira LH, Sterodimas A. Correction for the iatrogenic form of banana fold and sensuous triangle deformity. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32(6):923–927. Epub 2008 Jul 29

18 Pereira LH, Sterodimas A. Treatment of iatrogenic abdominal contour irregularities. Aesth Plast Surg. 2010;34(2):129–135. Epub 2008 Aug 28

19 Ullmann Y, Shoshani O, Fodor A, et al. Searching for the favorable donor site for fat injection: in vivo study using the nude mice model. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(10):1304–1307.

20 Rohrich RJ, Sorokin ES, Brown SA. In search of improved fat transfer viability: a quantitative analysis of the role of centrifugation and harvest site. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(1):391–395. discussion 396–7

21 Nicareta B, Pereira LH, Sterodimas A, et al. Autologous gluteal lipograft. Aesth Plast Surg. 2010;35(2):216–224.

22 Pereira LH, Sterodimas A. Macroscopic and microscopic proof of long-term survival of gluteal fat transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(4):162e–163e.

23 Pereira LH, Sterodimas A. Long-term fate of transplanted autologous fat in the face. J Plast Reconstr Aesth Surg. 2010;63(1):e68–e69. Epub 2009 Mar 12

24 Sterodimas A, de Faria J, Nicaretta B, et al. Tissue engineering with adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs): current and future applications. . J Plast Reconstr Aesth Surg. 2009;63(11):1886–1892.

25 Sterodimas A, de Faria J, Nicaretta B, et al. Cell assisted lipotransfer. Aesth Surg J. 2010 Jan-Feb;30(1):94–100. Rubin JP, Marra KG. Commentary. Cell-assisted lipotransfer (CAL). Aesth Surg J. 30(1): 82, 2010

26 Sterodimas A, de Faria J, Nicaretta B, et al. Autologous fat transplantation versus adipose derived stem cells enriched lipograft: a study. Aesth Surg J. 2011;31(6):682–693.

27 Toledo LS, Mauad R. Complications of body sculpture: prevention and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(1):1–11. v