Chapter 38 Liposuction and circumferential lower truncal dermatolipectomy

• The procedure of circumferential lower truncal dermatolipectomy is described and compared to alternative techniques.

• Main technical aspects and refinements are highlighted and described in the clinical context.

• The prevention, reduction and management of complications is demonstrated for this specific procedure.

• The different intraoperative steps are explained and how these enable procedure enhancement.

• The combination of liposuction and lower body contouring procedures has to be performed cautiously and restricted. Therefore, limitations are emphasized.

Introduction

The worldwide population of obese and morbidly obese individuals is growing faster than any other group. Consequently, we have a rapid increase in patients after weight loss, some of them through diet and exercise, and others who undergo a bariatric procedure with more or less irreversible gastrointestinal changes. Therefore, this new subfield of plastic surgery is gaining worldwide acceptance and there are many participating surgeons around the world. Following the establishment of modern body lift procedures by Ted Lockwood in the early 1990s1–5 and the progress in this surgical field, we nowadays benefit from different innovative approaches, which are all based on Lockwood’s philosophy. The main technical aspect, similar to modern face-lifting procedures, is the reconstruction of the superficial and deep connective tissue layers comparable to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) of the face. Nevertheless, it is essential to perform large-area tissue undermining and separation to allow a sufficient tissue mobilization and tightening of the affected areas with respect to an optimal result.

Preoperative Preparation

A precise physical examination and assessment of the medical history is mandatory in every patient. The examination of the lower body should include the upper and lower abdomen, the umbilical region, the midline region in standing and supine position, the flank and hip region with lateral thigh, the inner thigh, and additionally, the entire lower back region. For grading we recommend the Pittsburgh Rating Scale, published by Song et al.6

The ideal patient for circumferential reconstructive surgery meets the following criteria:

• Non-smoker or to quit smoking 6 weeks prior to surgery

• Weight stabilized for at least 6 months prior to surgery

• Highly motivated, athletically and socially stable

• Weight loss through diet and exercise

• Physically and mentally stable

• Circumferential tissue excess

• Maximal deflation of adipose tissue

The first consultation should further include a thorough and detailed explanation of the entire procedure, preferably on PowerPoint® presentations. It is essential to demonstrate complications on images to visualize and emphasize possibilities such as wound separation and impaired scarring. The translation-test by Aly has proven to be worthwhile in clinical practice. The patient is instructed to grasp his tissue surplus at the height of his waist and pull the excess tissue firmly upwards. The visible skin lift and body contour improvement obtained in this way reliably forecasts the outcome of the thigh appearance after lower body lift operations. Optimal results can be achieved with a normal BMI < 25. With a higher preoperative BMI the patient must be informed about an exponentially limited postoperative result. The upper limit for massive weight loss surgery should not exceed a current BMI of 32.7

Further, we endeavor to enhance the patient’s understanding of impaired skin quality due to weight loss and bariatric surgery. In this context, we cite the latest article on this issue and inform every patient about secondary skin relaxation in this specific patient group. Therefore it is not uncommon to perform a secondary tightening procedure in particular cases.8

Markings

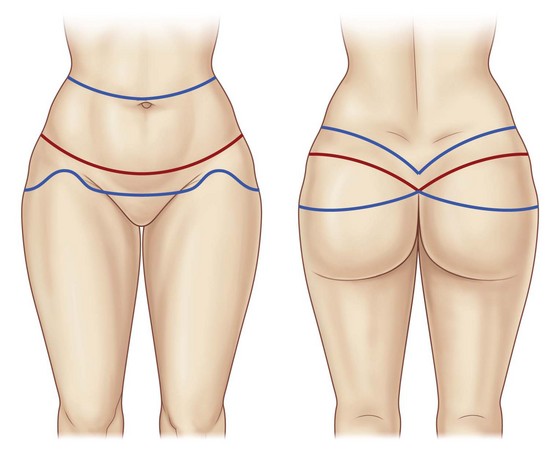

Initially, the boundaries of the patient’s preferred undergarment are marked in the standing position. The desired scar course is marked in red and double-checked by the patient. Dorsal markings are performed first. The posterior upper incision line runs about two to three finger breadths above the desired scar line and is marked in blue. The blue line, along its entire length, is then pulled caudally using the surgeon’s palm and is checked to make sure that it will reach the proposed red line of closure. In general, it should be at the lateral height of the umbilicus. The inferior proposed line of excision is estimated by strongly pinching the skin cranially, ensuring that approximately a quarter of the total resection height lies superior to the red scar line while the lower three quarters are inferior to it. The proposed inferior line of excision is an estimate that may need to be adjusted at the time of surgery. If avoidable, the anal cleft should not be elevated, since an elongation may result in patient dissatisfaction. It has been worthwhile to allow the upper incision line to run at a sharper angle into the anal cleft, in order to achieve an optical accentuation of the buttock form (Fig. 38.1).

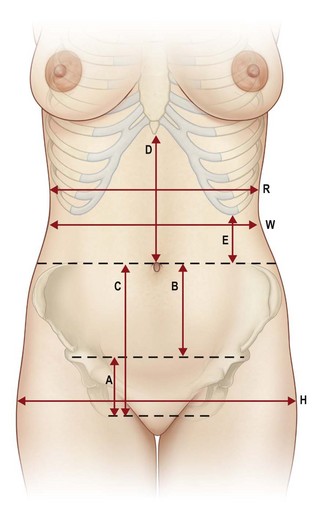

Next, the anterior markings are performed based on the frontal red line previously marked (Fig. 38.2). We routinely instruct the patient to firmly and symmetrically pull up the entire abdominal tissue, while we initially mark the midline, a minimal distance of 6 cm from the vulvar commissure (or base of the penis), and next the lower incision line from the midline point laterally, where they are connected to the lower dorsal line. Often the resulting scar line is placed too far cranially due to a lower incision line marked in the abdominal skinfold. Consequently, the mons pubis, which is often sagged and slackened, is not lifted. In more severe cases the lower incision line can be extended caudally in an elliptical or triangle shape into the mons pubis region for an effective local skin tightening. Nevertheless, it is essential to leave a distance of 6 cm to the upper vulvar commissure (or base of the penis) (Fig. 38.3). The upper incision line is then continued from the lateral aspect of the dorsal upper line medially to the height of the umbilicus. In cases of distinct tissue surplus in the upper abdomen we routinely inform the patient about the option of a fleur-de-lis incision pattern during the first consultation. If the patient agrees to this additional scar line, we draw the midline cranially to the xiphoid. The vertical incision line is then evaluated by pinching and marked in an elliptical shape, starting two finger breadths below the xiphoid. This is mandatory to avoid a further cranial scar ending. Also, it is advisable to mark the vertical incision lines in standing position, since the tissue tends to drop laterally and backwards in supine position. The upper horizontal incision line is then marked approximately one finger breadth below the height of the umbilicus.

FIG. 38.2 Anatomical landmarks.

(from Richter DF, Stoff A. Abdominoplasty procedures. In: Plastic Surgery 3rd edition (Neligan P ed.) Elsevier, Saunders, St. Louis, 2012, with permission from Elsevier).

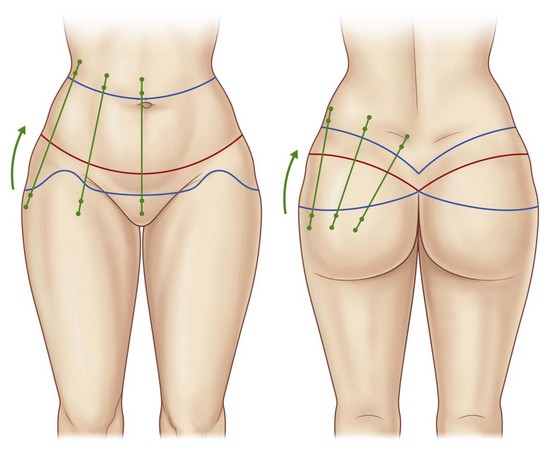

Importantly, dorsal vector lines are marked to allow a mediocranial rotation of the gluteal and thigh region and a consequent sculpturing of the waist (Figs 38.3 and 38.4). A final check of the markings should be performed in the patient’s supine and prone positions.

FIG. 38.4 Intraoperative marking of vectors and intraoperative positioning in prone position (with permission from Elsevier).9

For additional liposculpturing of the flank, back or lateral thigh regions, the markings are made in the typical manner. We advise refraining from excessive liposuction in the undermined gluteal area, since any additional impairment of microcirculation in this area may result in skin necrosis. Patients after massive weight loss frequently present with significant adipose tissue redundancy in the area of the circumferential thighs, we routinely perform widespread tissue reduction by vibration-assisted liposuction in this area during the initial circumferential lower truncal dermatolipectomy.9

General Considerations

Accurate patient positioning is essential for avoidance of scar asymmetry and impairment of tissue perfusion in the areas of maximal pressure. The entire team, including anesthesiologists, surgical nurses and surgeons must constantly and conscientiously check the patient’s positioning. Pressure necrosis can arise around the periorbital regions and at the breasts, particularly in the prone position.10

We routinely install a urinary catheter and wrap the lower legs with compression bandages for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prevention. Further, we administer a single-shot antibiotic to every patient. In specific cases the postoperative continuation of antibiotic prophylaxis may be considered.11

Surgical Technique

Dorsal Preparation

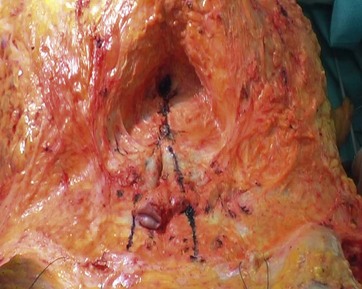

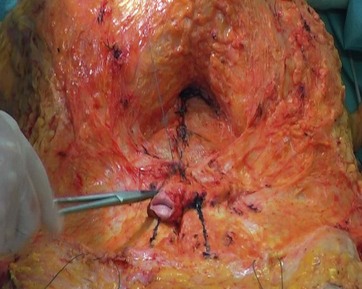

The initial skin incision (utilizing the cold blade or alternatively the Colorado® Microdissection needle) is made along the superior marking line and is carried out down to the level of the underlying superficial fascia, which is exposed using the Colorado® Microdissection needle or alternatively the Harmonic™ ultrasound scalpel, both of which easily separate the superficial lamellar from the subfascial lobular fat. Next, the dissection is continued inferiorly just above the robust white superficial fascia. The dissection level above the superficial fascia differs considerably from the original technique by Lockwood, who dissected subfascially. The preservation of fascia to the deep gluteal fat as the “gluteal SMAS” is conceptionally similar to the “facial SMAS” used in face-lifts. The superficial fascia is dissected at the height of the inferior resection line, before flap mobilization is continued caudally. Further, this allows a reconstruction of superficial fascia upon wound closure. Lateral gluteal adhesions are released caudally up to the gluteal fold height, before dissection is continued to the lateral thigh, where the preparation level is above the aponeurosis of the tensor fascia lata muscle. Further distal mobilization of the lateral thigh can be carried out bluntly using the Lockwood underminer. With completion of dissection, the waist and gluteal fatty tissue is widely mobilized and covered with robust superficial fascia. This is particularly suited for autologous gluteal augmentations, since patients after massive weight loss frequently suffer from flattened buttocks. For this purpose, two to three 1×0 Ethibond threads (Ethicon, USA) are sutured from lateral to medial, grasping the stable fascia and consequently displacing the gluteal fatty tissue to the middle of the buttock. For cranial repositioning, three to four 1×0 Ethibond threads (Ethicon, USA) are sutured from caudal to cranial at the medial aspect of the buttocks. By reconstruction and tightening of the gluteal adipose tissue, the gluteal flaps are lifted cranially with a consequent final skin closure under less tension. Further, this maneuver is able to improve the shape of the waist (Fig. 38.5).

The detachment in the zones of adherence combined with an extended mobilization allow an enormous tightening of the skin. The stage of resection should always be supervised by the “leading” surgeon in terms of symmetrical resection. We advise to utilize bullet forceps for determination of the amount of resection. The marked vector lines (Fig. 38.4) are incised from medial to lateral and adjusted for maximum tension. The redundant medial, central and lateral gluteal flaps arising in this way are measured precisely in tensed condition for symmetrical resection, which is subsequently carried out between the clamps (Figs 38.6 and 38.7).

FIG. 38.6 Intraoperative demonstration of flap dissection to ensure symmetrical resection (with permission from Elsevier).9

FIG. 38.7 Each flap should be measured in comparison to the contralateral side (with permission from Elsevier).9

Before patients are turned into the supine position we perform a temporary closure of the lateral skin surplus utilizing a stapler and occlusive Opsite® foil.9

Anterior Preparation

Standard Technique

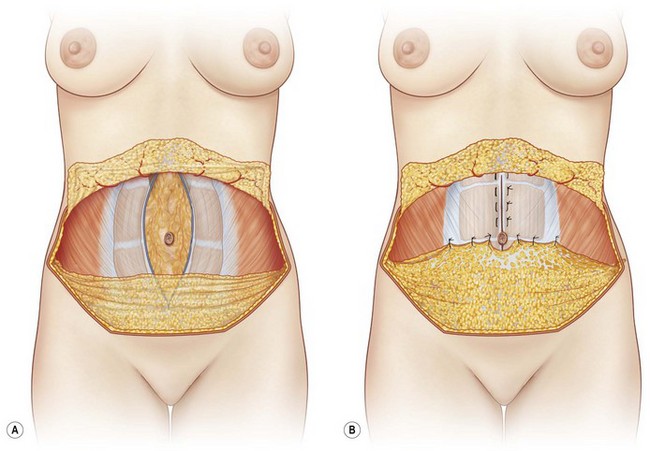

With all techniques the dissection level is performed above Scarpa’s fascia (Figs 38.8–38.10), entailing a number of key advantages: long-lasting swellings can be prevented because the underlying lymphatic vessels are preserved, and the stretching of the SFS craniomedially provides an additional “inner traction” on the deep penetrating fascia system of the thigh. The SFS may then be fixated with 1/0 Ethibond sutures (Ethicon, USA) to the anterior rectus fascia (Fig. 38.11). Approximately three finger breadths below the umbilicus, Scarpa’s fascia is dissected and further mobilization of the abdominal flap is performed cranially on the anterior rectus fascia (Fig. 38.12). The central supraumbilical adhesion zone is sharply dissected between both rectus muscles, preserving the laterally incoming perforator vessels (Fig. 38.13).

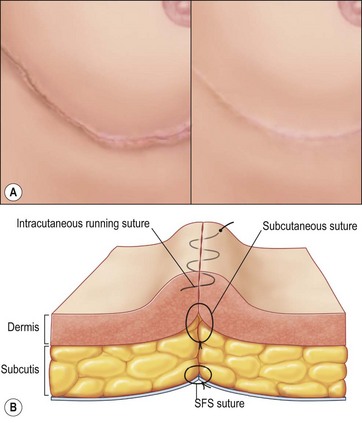

Rectus diastasis and/or abdominal fascial laxity are corrected by vertical anterior rectus fascia plication (Figs 38.13 and 38.14). In simple cases, midline plication is sufficient; in more pronounced cases of fascial laxity additional oblique infraumbilical plications may be indicated. Lateral extended release of the abdominal flap may be necessary to prevent tissue bulging in the midline. Since the umbilicus is often prolonged in patients after massive weight loss, we shorten the entire umbilical stalk with a remaining 2–3 cm deep umbilical tunnel. The umbilicus base is now fixated at 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock to the anterior rectus fascia. The new position of the umbilicus is marked on the abdominal flap and a small distally based triangular or U-shaped pedicular flap is incised, followed by an extensive periumbilical fat removal, and continued cranially in the midline for accentuation of a “Champagne groove”. Temporary wound closure is performed with bullet forceps, followed by reconstruction of the SFS with PDS® 2×0 (Ethicon, USA). A multilayer wound closure with 2-0 and 3-0 Monocryl® (Ethicon, USA) follows prior to intracuticular suturing. Because of the wound length, 2-0 Monocryl® (Ethicon, USA) is advisable (Fig. 38.15). Finally, Steri-strips are applied as described later. Alternatively, wound closure at the subdermal level may be performed with a single resorbable barbed suture (PDO 3-0, Quill®) in running manner. Skin closure may then be performed with an intracuticular monofil or barbed suture and alternatively with a two component skin closure system (refer to section Operation Time).

Fleur-de-lis Technique

In patients with extreme weight loss (>120 kg) and consecutive skin redundancy the abdominal tissue tightening mostly requires fleur-de-lis resections, which significantly reduce the lower abdominal circumference. In the thigh area these patients additionally present extensive circumferential tissue redundancies, which we prefer to remove by a medial scar approach, beginning from the lower abdominal scar at the mons pubis and descending caudally to the medial thigh region. In this regard, we recommend performing the closure of the abdominal region while shifting the lower lateral and anterior thigh tissue medially. This allows a circumferential tightening of the entire thigh circumference. Immediately and in the first weeks postoperatively, patients have to deal with a significant skin surplus at the lateral mons pubis region, which will be eliminated by the following inner thighplasty. Taking this maneuver into account, this modification allows an optimal tightening of the entire thigh simply by two procedures. Representative case studies are shown in Figs 38.16–38.27.

FIG. 38.19 Six-months postoperative anterior view after circumferential lower truncal dermatolipectomy.

FIG. 38.20 Six-months postoperative lateral view after circumferential lower truncal dermatolipectomy.

FIG. 38.21 Six-months postoperative posterior view after circumferential lower truncal dermatolipectomy.

Optimizing Outcomes

Operation Time

We perform the procedure with only two turns, starting in the prone position and completing in the supine position. This enables a considerable decrease in operation time and allows one team to operate simultaneously on each half of the patient’s body. However, one surgeon has to take the leading position, controlling for an equal resection and standard operative performance. Further, the application of running barbed sutures for subdermal closure and the two component wound closure systems, including an adhesive mesh tape and a next generation cyanoacrylate (PRINEO™ Skin Closure System), may decrease the operation time markedly.12

Symmetry

• Patient positioning has to be checked precisely after each position change. Redundant tissue resection and umbilical insertion should be performed prior to bending patients for wound closure.

• Formerly, with three positions, including three patient turns, we observed asymmetric scar courses, since the lateral positioning inhibited effective control of symmetry during the operation.

• In prone/supine positioning we advise a “leading” surgeon ensures simultaneous and comparable resection and wound closure tension. In this regard it has proved to be useful to divide operation areas into precisely defined sectors using suitable vector lines (Fig. 38.4).

Wound Healing Disorders

For this reason we advise respecting the following instructions:

• Supraumbilical mobilization should include the entire midline up to the xiphoid and should not extend to the costal margin. Perforators should be preserved to the maximal tension, especially in smokers. With adequate reconstruction of the SFS, wound closure on skin level should be performed tension free with respect to the flap perfusion.13 In thicker abdominal flaps, the distal portion of the sub-Scarpal fatty tissue (inferior to the new umbilicus) can be resected with ease.14

• In fleur-de-lis resection we refrain from lateral undermining of both abdominal flaps. Again, the distal sub-Scarpal fatty tissue of abdominal flaps can be resected. We recommend avoiding any mobilization inferior to the lower incision line.

• Profound knowledge of the gluteal and thigh perfusion is very important for a complication-free outcome, since discontinuous undermining may be carried out all the way caudally to the knee area. If necessary, the upper lateral and anterior thigh can be mobilized from the muscle layer without significant consequences, and dissected precisely by preserving the subcutaneous vascular plexus. If patients present with excessive adipose tissue redundancy in the lateral thigh area, we recommend liposuction of the deep fat layer prior to the gluteal dissection. In these particular cases we constrain lateral and gluteal dissection.9,15

Suture granulomas due to the large number of resorbable sutures occur frequently and may cause local infections with wound openings. In patients with bariatric surgery we endeavor to monitor proteins, vitamin C, zinc, blood glucose, as well as hemoglobin levels.10,16

Scarring

Publications on the superficial fascial system by Lockwood in the early 1990s have brought a new understanding, including with respect to scar formation.1–3 Dissection on the level of the superficial fascia in the buttock area preserves a stable layer for reconstruction and tissue transposition of the gluteal fatty tissue. Further, the reconstruction of the SFS enables a tension free closure on skin level, in addition to an everting skin closure for optimal scar formation (Fig. 38.15).

Seroma

Because of the large area of the wounds, accumulations of wound fluid (seromas) may cause postoperative problems. Particularly at the lateral thigh, seroma may occur down to the knee region due to gravity. Seroma formation cannot be prevented with any degree of certainty.17–19 Suction-assisted drains in the area of the lateral outer thigh are left until drainage is less than 30 ml within 24 hours. Progressive tension sutures are helpful tools for the reduction of dead space and may limit accumulation of fluids.20 The potential of the ultrasonically activated Harmonic™ scalpel for reducing seroma formation in circumferential body lift procedures has been demonstrated in studies.21

Buttock and Waist Formation

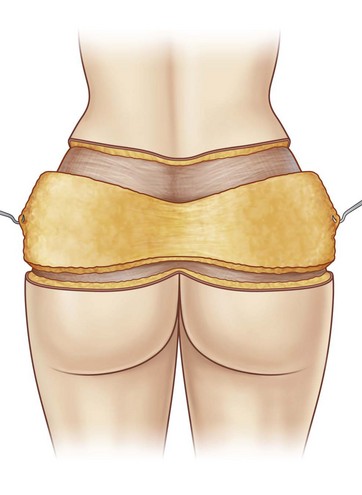

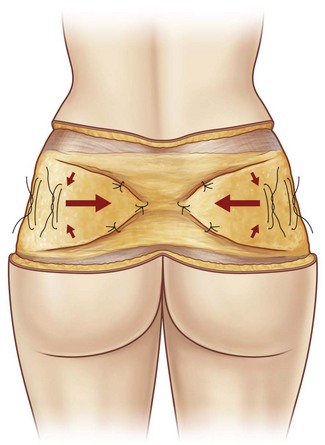

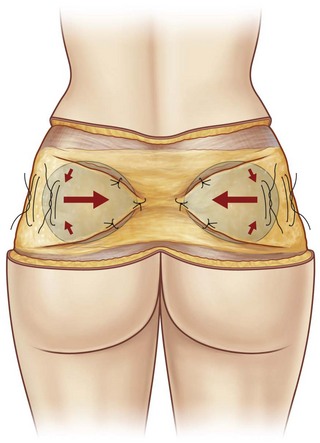

After massive weight loss patients often present with a flattened buttock. Circumferential lower body contouring procedures remove redundant skin and adipose tissue, which may prohibit any contour improvement in the gluteal region. For this reason, it is of huge importance in certain cases to restore gluteal adipose tissue for gluteal enhancement with autologous tissue transpositioning (transposition-gluteoplasty) during circumferential lower truncal dermatolipectomy. This maneuver enables an enhancement of gluteal projection, gluteal shape and waist formation22 (Figs 38.28–38.36).

FIG. 38.28 Schematic demonstration of gluteal adipose tissue preservation during dorsal preparation (with permission from Elsevier).9

FIG. 38.29 Schematic demonstration of gluteal adipose tissue preservation followed by suture placement in vertical and horizontal directions (with permission from Elsevier).9

FIG. 38.30 Vertical and horizontal suturing for maximal tissue accumulation in the medial and cranial direction (with permission from Elsevier).9

Complications and Their Management

For prevention and risk minimization of seromas we recommend the following:

• Preparation with a Colorado® microdissection needle

• Alternative preparation with an ultrasonic scalpel (Harmonic™)

• Intraoperative tissue cooling and dampening with wet compresses and initial infiltration

• Reduced operation time and minimal heat development

• Preservation of Scarpa’s fascia

• Meticulous coagulation for minimal bleeding, ligation of arterial perforators

• Anesthesiological-induced increase of blood pressure during hemostasis

• Early revision of postoperative hemorrhage

• Insertion of 5–7 drains in lower circumferential procedures

• Drain removal with drainage volume of maximum 30 ml per 24 hours

• Perioperative protein, zinc and vitamin substitution for wound healing enhancement

• Individually adapted compression garments to reduce shearing forces postoperatively.

We recommend weekly wound inspections per manual and ultrasonic examination within the first 4 weeks postoperatively. The sooner a seroma is detected, the earlier it can be evacuated. If patients are inadequately guided during the postoperative phase, they might present with an unexpected wound separations with deflation of an undetected seroma. Once a seroma has been detected it should be evacuated under sterile conditions and checked at least twice a week. For persisting seroma we recommend the intracavitary injection of 200 mg doxycycline.9

1 Lockwood TE. Superficial fascial system (SFS) of the trunk and extremities: a new concept. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(6):1009–1018.

2 Lockwood TE. Transverse flank-thigh-buttock lift with superficial fascial suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(6):1019–1027.

3 Lockwood TE. Lower body lift with superficial fascial system suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92(6):1112–2112. Nov

4 Lockwood TE. The role of excisional lifting in body contour surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23(4):695–712.

5 Lockwood TE. Maximizing aesthetics in lateral-tension abdominoplasty and body lifts. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31(4):523–537.

6 Song AY, Jean RD, Hurwitz DJ, et al. A classification of contour deformities after bariatric weight loss: the Pittsburgh Rating Scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;116(5):1535–1544.

7 Aly AS. Body Contouring after Massive Weight Loss. St.Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2006.

8 Orpheu SC, Coltro PS, Scopel GP, et al. Collagen and elastic content of abdominal skin after surgical weight loss. Obes Surg. 2010;20(4):480–486.

9 Richter DF, Stoff A, Velasco FJ, et al. Circumferential lower truncal dermato-lipectomy. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35(1):53–71.

10 Rubin JP, Nguyen V, Schwentker A. Perioperative management of the post-gastric-bypass patient presenting for body contour surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31(4):601–610. vi. Review

11 Richter DF, Stoff A. Lower body contouring procedures. Chirurg. 2011;82(9):797–800. 802–806, [German]

12 Richter DF, Stoff A, Blondeel PN, et al. A comparison of a new skin closure device and intradermal sutures in the closure of full thickness surgical incisions. Plast Reconstr Surg, in press.

13 Huger WE, Jr. The anatomic rationale for abdominal lipectomy. Am Surg. 1979;45(9):612–617.

14 Hunstad JP, Repta R. Atlas of Abdominoplasty. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

15 Richter DF, Stoff A, Uckunkaya E, et al. Perils and pitfalls in lower body lifts. Int J Adipose Tissue. 2007;1(1):12–16.

16 Agha-Mohammadi S, Hurwitz DJ. Enhanced recovery after body-contouring surgery: reducing surgical complication rates by optimizing nutrition. Aesth Plast Surg. 2010;34(5):617–625.

17 Aly AS, Cram AE, Chao M, et al. Belt lipectomy for circumferential truncal excess: The University of Iowa experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:398.

18 Kenkel JM. Body contouring surgery after massive weight loss. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;Suppl 117:1–86.

19 Rohrich RJ, Gosman AA, Conrad MH, et al. Simplifying circumferential body contouring: the central body lift evolution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(2):525–535. discussion 536–538

20 Baroudi R, Moraes M. Philosophy, technical principles, selection, and indications in body contouring surgery. Aesth Plast Surg. 1991;15:1–18.

21 Stoff A, Reichenberger M, Richter DF. Comparing the ultrasonically-activated scalpel (HarmonicTM) versus high-frequency electrocautery on postoperative serous drainage in massive-weight-loss surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(4):1092–1093.

22 Richter DF, Stoff A. Autoaugmentation of the buttocks during circumferential body lift without flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. in preparation.

Gonzales-Ulloa M. Belt lipectomy. Br J Plast Surg. 1961;13:179.

Hurwitz DJ. Single-staged total body lift after massive weight loss. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52(5):435–441. discussion 441

Richter DF, Stoff A. The Scarpa-Lift – a novel technique for minimal invasive medial thigh lifts. Obes Surg. 2011;21(12):1975–1980.

Malinowski SS. Nutritional and metabolic complications of bariatric surgery. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(4):219–225.

Nemerofsky RB, Oliak DA, Capella JF. Body lift: an account of 200 consecutive cases in the massive weight loss patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(2):414–430.

Song AY, Rubin JP, Thomas V, et al. Body image and quality of life in post massive weight loss body contouring patients. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(9):1626–1636.

Strauch B, Herman C, Rohde C, et al. Mid-body contouring in the post-bariatric surgery patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7):2200–2211.

Xanthakos SA, Inge TH. Nutritional consequences of bariatric surgery. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9(4):489–496.