CHAPTER 31 Liposuction

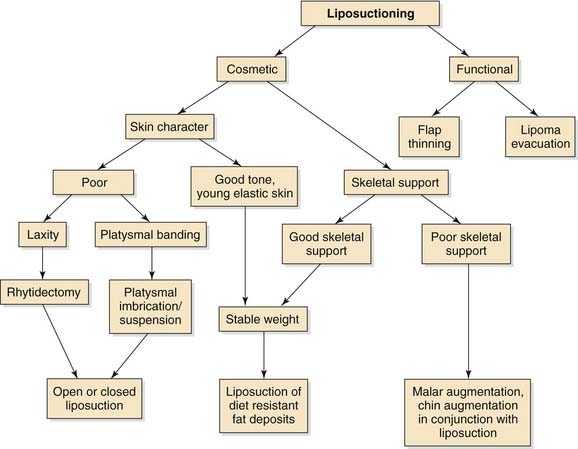

Suction lipectomy is an effective means of recontouring the face that has been popularized and refined over the past 30 years.1–5 As with all cosmetic surgery, understanding the anatomy, physiology, and changes that result from the aging process is imperative. On the basis of these changes, a logical approach to the integration of suction-assisted lipocontouring into the practice of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery is possible (Fig. 31-1).

The distribution of body fat is a consequence of genetics and is influenced by hormones, diet, exercise, medications, and patient age. It has become apparent through tissue culture studies that, after a critical mass within an adipocyte has been reached, hyperplasia can occur.6 Although the mechanism of adipocyte hyperplasia has not yet been determined, the consensus remains that any significant change in fat deposition occurs through the enlargement rather than the addition of cells.7 Diet-resistant localized fat deposits, which are ideal for lipocontouring, may represent localized adipocyte hyperplasia. Liposuction reduces the number of adipocytes regardless of their size and therefore should yield a lasting result, unless excessive weight gain occurs. The liposuctioned regions of hypertrophy should respond to weight gain in a fashion that is similar to adipocytes in other regions of the body and, therefore, should be resistant to significant contour changes that are out of proportion with overall weight fluctuation.

Liposhaving has recently been advocated as an alternative to liposuction. In this technique, a soft tissue shaver is used with minimal suction to gently shave adipocytes.2 The safety of this technique is of concern, and further investigation is under way. With liposuction and liposhaving, preserving important structures and maintaining bridges of uninterrupted tissue between the deep and superficial layers in an effort to maintain a healthier skin flap are the principles to be followed. Ultrasonic liposuction adds the mechanical agitation of the cannula to assist in the dissection and release of adipocytes and is usually done in conjunction with tumescent infiltration.8 Recently the use of ultrasonography has been used both internally and externally to assist with liposuction. The ultrasonic energy is transferred into mechanical vibrations that cause the microcavities in the adipocytes to implode, thereby resulting in the liquefaction of the fat.9 Multiple studies have shown potential complications with the use of subcutaneous ultrasonic energy resulting from heat generated at the cutaneous incision site and the more distal subdermal sites.8–10 To date there are no controlled studies that demonstrate any added benefit from ultrasonic-assisted liposuction in the face and neck as compared with the standard technique.

Patient Selection

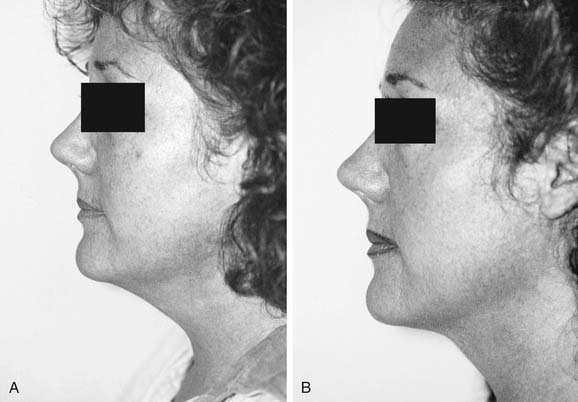

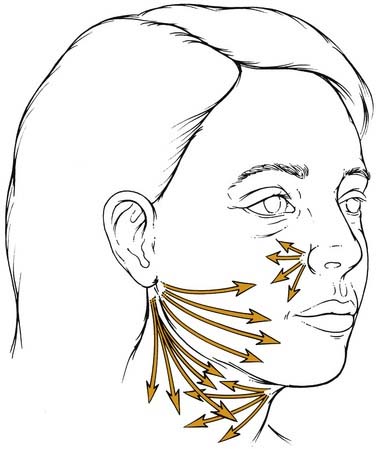

One of the greatest challenges with facial plastic surgery is the art of proper patient selection, and lipocontouring is no exception. Patient selection begins with an informal interview to get a sense of the patient’s motivation, expectation, and cooperation. The patient’s motivation for pursuing a cosmetic procedure should be investigated. Some patients expect a change in external appearance to have a significant impact on their personal or professional lives (e.g., to get a promotion at work, to dissuade a spouse’s infidelity); these patients are bound to be disappointed. A patient’s expectations should be precise and realistic. Lipocontouring allows for the removal of a particular area of subcutaneous fullness; although it will not have a direct impact on other areas, the change in contour may create the illusion of affecting surrounding areas and thereby influence the overall balance of the face. For example, a submental lipectomy may appear to enhance chin projection (Fig. 31-2), shorten the vertical height of the face, and create a wider and more cherubic-appearing face. Likewise, facial and jaw lipocontouring may create a more angular facial contour (Fig. 31-3) but will not increase malar projection and could create a wasted appearance. The patient’s expectations should be communicated preoperatively. Computer imaging can aid in communication, but it can also be misleading if not used prudently. Cooperation is imperative during the postoperative phase. A patient who cannot avoid the sun or continue with a pressure dressing postoperatively is a poor candidate for lipocontouring and should be dissuaded from pursuing surgery.

The ideal patient is not particularly overweight and has a localized fullness that is the result of an isolated pocket of subcutaneous adipose tissue refractory to weight loss. A patient who reports a familial pattern or who has had a double chin since childhood is a good candidate. The submental, melolabial, submandibular, and buccal areas lend themselves well to lipocontouring. Younger patients tend to have greater skin elasticity, which contracts better on the new subcutaneous contour; these candidates are ideal for isolated lipocontouring. Conversely, the loss of skin elasticity and turgor in older patients will necessitate a skin-tightening procedure (see Fig. 31-17). Obese patients have excess adipose tissue in multiple layers and do not respond well to lipocontouring. Moreover, this procedure is not intended to replace general weight control.

Common Pitfalls

Patient evaluation may yield common pitfalls that lead to untoward effects:

Instrumentation

The instrumentation for lipocontouring the face and neck remains uncomplicated: a vacuum generator with the capability of reaching 1 atmosphere of negative pressure, a disposable canister to function as a trap for the aspirated fat, sterile tubing, and relatively few liposuction cannulas. The cannulas are available from multiple manufacturers. Some surgeons prefer the round over the spatulated tip, and some prefer the cannulas in which the distal 1.5 to 2 cm is slightly angulated. Angulation of the distal portion allows the positioning of the aspiration port (on the deep surface away from the skin) to be determined on palpation. Cannulas that are 3 to 6 mm are most useful for liposuction. For liposuction. a soft tissue shaver is used (Fig. 31-5), such as the endoscopic soft tissue shaver or the cartilage shaver used in joint surgery. Cannula size varies from 2.9 to 4.8 mm for liposhaving.

Technique

Patient Preparation

Preoperatively, the patient is given routine instructions, such as to take nothing by mouth after midnight, to avoid any medications that alter platelet function, and to avoid the consumption of alcohol. Patients are instructed to wash their face and hair with an antiseptic soap and to remove all makeup and hair-care products. Prescriptions for antibiotics and pain medicine are given to the patient preoperatively to fill before the surgical procedure. When the patient arrives for surgery, an intravenous line is started and preoperative antibiotics are administered. The patient is marked in the upright position, with the areas to be suctioned circumscribed and the zones of feathering indicated (Fig. 31-6). Anatomic landmarks (e.g., the angle of the mandible, the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the hyoid bone and thyroid notch) may also be marked (see Fig. 31-6). After marking has been completed, the patient is taken to the operative suite, where sedation and infiltration are carried out before preparing and draping the patient. This approach allows additional time for vasoconstriction to occur before surgery.

Surgery

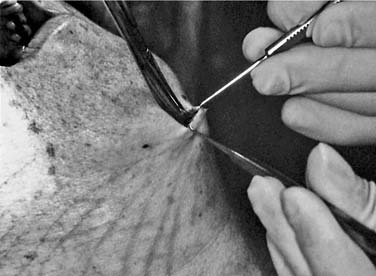

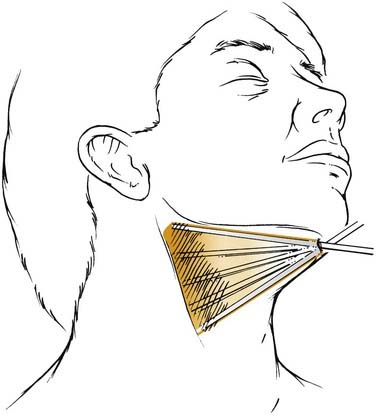

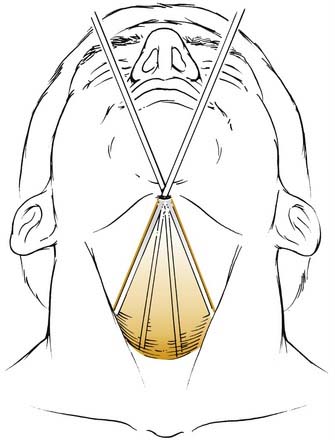

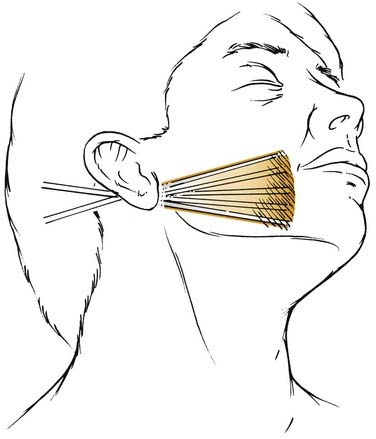

A nonaspirative cannula is used to make multiple interconnecting tunnels throughout the region to be aspirated. During the nonaspirative phase of flap elevation, it is important to follow the same technique that would be followed when aspirating. The aspiration port should be kept on the deep surface. The skin incision is stabilized with countertraction using a skin hook, and the correct plane is identified with scissors (Fig. 31-7). Graduating cannula sizes are used to develop the tunneling after the cannula is in the correct plane (Fig. 31-8). The free hand is used to palpate the cannula tip and determine the depth of dissection (Fig. 31-9). Dissection is carried out in a spokelike fashion from the incision; multiple distal pseudopods from each spoke are used to ensure that lateral aspiration with feathering is executed thoroughly (Fig. 31-10). Additionally, nonaspiration tunneling is performed beyond the margins of the area to be aspirated to allow for complete redraping. The surgeon should concentrate on distal aspiration, because each repetitive motion (Fig. 31-11) of the cannula crosses over the proximal adipose tissue in the region adjacent to the original insertion, possibly resulting in a hollowed appearance at that point. Hollowing and inconsistent flap elevation can also be avoided by palpating the cannula tip and preserving some fat on the undersurface of the flap.

Figure 31-8. Use of the suction cannula to develop subcutaneous tunnels while stabilizing the skin with a skin hook.

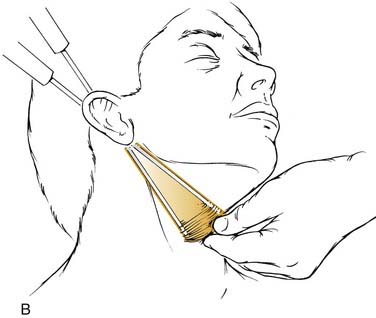

After complete nonaspiration elevation has been accomplished, the suction is applied at one atmosphere of negative pressure, and multiple passes are re-executed. The assessment of evacuated fat may require the release of the vacuum so that any fat in the cannula and tube may be drawn into the canister; this approach may be necessary when the volume removed is small. Aspiration from the postauricular incision includes the jowl, posterior cervical, and submandibular regions (Fig. 31-12).

Cross-hatching occurs with the submandibular portions aspirated from the submental incision. In aspiration of the jowl, it is imperative to release suction when withdrawing the cannula over the posterior facial soft tissue and masseter because this area may not require aspiration, and a groove may be created in the posterior face. The margins can be tapered with a smaller cannula or with fewer passes. Liposuction of the melolabial fold or, more appropriately, of the superior border of the fold is performed with a small cannula through an incision in the nasal vestibule (Fig. 31-13).

Figure 31-13. Sites that can be approached through the submental, postauricular, and vestibular incisions.

With liposhaving (Fig. 31-14), flap elevation is done in a similar fashion. The cannula is inserted with the blade inactive. After the blade is activated, extreme care should be taken at the incision to avoid damage to the skin margins. The cannula is passed in a more delicate fashion and at a slower rate than it is with liposuction, because shaving—rather than avulsion—is occurring. Minimal amounts of suction are applied, and the cannula must remain in motion when the blade is active, because it will shave progressively deeper, thereby jeopardizing other structures.

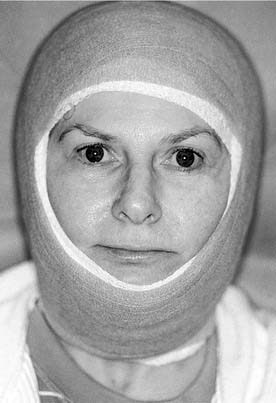

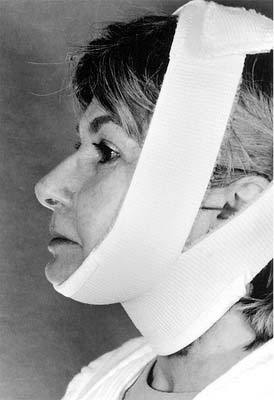

Dressing

Postoperatively, all patients require a pressure dressing circumferentially around the head and neck. Antibiotic ointment is first applied to the incision and then covered with a nonadhesive dressing. Fluffs are then placed over the region that has been aspirated, and a rolled cotton gauze is used to hold these fluffs in place. Coban R (3M; St Paul, Minn) dressing is applied using light but continuous pressure (Fig. 31-15). The dressing is left undisturbed for 2 to 3 days and then removed. After this, an elastic dressing is used at night and when indoors, and is changed by the patient as needed (Fig. 31-16). Antibiotics are used in all elective surgeries; drains are not routinely used. Liposuction is usually not painful, but the circumferential dressing can be uncomfortable and produces anxiety in some patients. For this reason, mild analgesics are helpful. Elevation of the head and the continuous use of ice packs minimize swelling.

Summary

Lipocontouring is a necessary adjunct to a facial plastic and reconstructive practice. Multiple tools are available and should be judged individually. Patient selection and education are paramount to achieving satisfaction. The judicious use of liposuction in conjunction with other cosmetic procedures will enhance the results and the satisfaction of both the patient and the surgeon (Fig. 31-17).

Adamson PA, Cornier R, Tropper GJ, et al. Cervical facial liposuction results and controversies. J Otolaryngol. 1990;19:267-273.

Becker D, Park SS, Gross CW. Results from Current Investigation. University of Virginia; 1995.

Coleman S. Structural Fat Grafting. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2004.

Cueva R, Thomas JR, Davidson M. Liposuction to debulk the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. J Otolaryngol. 1988;9:106.

Markman B. Anatomy and physiology of adipose tissue. Clin Plast Surg. 1989;16:235.

Obagi S. Autologous fat augmentation: a perfect fit in new and emerging technologies. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2007;15:221-228.

Schrudde J. Lipexeresis as a means of eliminating local adiposity. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1980;4:215.

Shiffman MA, Giuseppe AD, editors. Liposuction Principles and Practices. Germany: Springer-Verlag, 2006.

1. Fournier PF. Why the syringe and not the suction machine? J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:1062.

2. Gross CW, Becker DG, Lindsey WH, et al. The soft-tissue shaving procedure for removal of adipose tissue: a new, less traumatic approach than liposuction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1117.

3. Illouz YG. Body contouring by lipolysis: a 5 year experience with over 3000 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72:591.

4. Kesselring UK, Meyer R. A suction curette for removal of excessive local deposits of subcutaneous fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;63:305.

5. Mladick RA. Lipoplasty: an ideal adjunctive procedure for the face lift. Clin Plast Surg. 1989;16:333.

6. Van R. The adipocyte precursor cell. In: Cryer A, Van R, editors. New Perspectives in Adipose Tissue. London: Butterworths, 1985.

7. Kridel RWH, Pacella BL. Complications of liposuction. In: Eisele D, editor. Complications of Head and Neck Surgery. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1992:791.

8. Igra H, Satur NM. Tumescent liposuction versus internal ultrasonic-assisted tumescent liposuction: a side to side comparison. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:1213.

9. Kloehn RA. Commentary on ultrasound-assisted lipoplasty: task force July 1966 report to membership. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1198.

10. Setliff RC. The hummer. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1996;29:93.