Chapter 22 Lipoabdominoplasty with previous flap resection

• Lipoabdominoplasty with previous flap resection is a complete method for the correction of esthetic abdominal deformities by removing excess skin and subcutaneous fat whilst also repairing the rectus diastasis and tissue laxity.

• Abdominal surgery has been extensively revised and published since Dermars and Marx in 1890 and Kelly1 in 1899.

• It is important to note the following:

Introduction

Surgeons such as Callia,2 Pitanguy,3 Pontes,4 Baroudi,5 Avelar,6 Matarasso,7 Lockwood,8 Guerrero Santos,9 and many others around the world have contributed to the development of surgery in the abdominal area.

Concerning vascularization studies, contributions from El Mrakbey,10 Boyd and Taylor11 and others have highlighted the associated morbidity related to the extension of the undermining in these procedures.

The classifications of the pathology, according to Pitanguy12 and Bozola,13 allowed more precise and correct surgical indication by choosing the technical options and the extension of each procedure.

Baroudi’s5 stitch technique greatly diminished the occurrence of seroma formation by plicating the abdominal flap to the aponeurosis. Seroma formation, together with infection and skin necrosis, are the major complications of this procedure in the postoperative period.

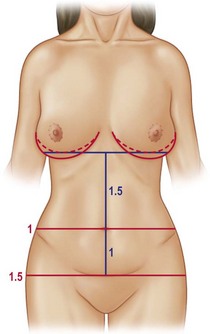

Bozola13 described the umbilical position, which can be measured in a geometric proportion of 1 for the infraumbilical portion and 1.5 for the supraumbilical area, giving a harmonic relationship to the abdomen (Fig. 22.1). The umbilical position will be the parameter for our assessment concerning the removal of the infraumbilical flap, so we must be extremely careful with those patients having a high umbilical scar position.

However, the greatest advancement in the evolution of abdominoplasty was the use of liposuction. The liposuction studies by Illouz,14 Avelar,6 Saldanha,15 Hunstad16 and Klein17 highlighted the safety of this procedure in regular association with traditional abdominoplasty. Liposuction decreases fat thickness and reduces the undermining required. This results in both harmonious and satisfactory outcomes for the patients and their respective surgeons.

In our clinical practice we are in favor of the previous resection of the abdominal flap as proposed by Pontes4 since 1964. The ease of the resection, the absolute control of bleeding, scar symmetry, and improved speed and efficiency of the procedure are our critical points to advocate the abdominoplasty with previous flap resection as our routine technique. In addition, improved flap handling is another distinct advantage and further emphasizes our preference for this procedure.

Preoperative Preparation

Patient Selection

Type I: Abdominal lipodystrophy without skin flaccidity, absence of diastasis or hernia, umbilical scar in normal anatomical position.

Type II: Infraumbilical abdominal lipodystrophy with discrete cutaneous flaccidity, presence or absence of diastasis, umbilical scar in normal anatomical position.

Type III: Generalized abdominal lipodystrophy with moderate cutaneous flaccidity, and presence or absence of diastasis.

Type IIIA: Umbilical scar in normal anatomical position.

Type IIIB: Umbilical scar in excessively high anatomical position.

Type IV: Abdominal lipodystrophy with marked cutaneous flaccidity, the presence of muscular diastasis or eventrations with or without associated umbilical scar in a normal anatomical position.

Type V: Marked abdominal cutaneous flaccidity with or without lipodystrophy; presence of scar at the midline of the abdomen. The umbilical position is in a normal or altered anatomical position.

Type VI: Marked generalized abdominal lipodystrophy and flaccidity. These patients are generally not considered good candidates for an esthetic surgical procedure. Patients in this group should undergo a strict clinical treatment to lose weight, frequently needing the attention of a multidisciplinary team (e.g., endocrinologist, physiotherapist, nutritionist, physiologist, etc.).

So, with precise analysis we can choose the exact surgery type for each case.

Surgical Technique

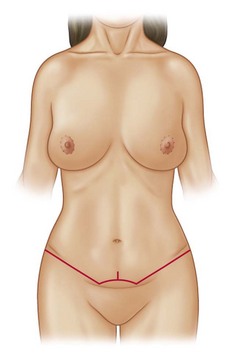

In a standing position we draw an area corresponding to a bikini shape (Fig. 22.2). The lateral lines are parallel to the inguinal crease, reaching a point demarcated on the natural crease of the abdomen on the hips (Figs 22.3 and 22.4).

The opposite side will be drawn in the same way and confirmed with a ruler and a compass.

In sequence we draw a semicircle bordering the inferior pole of the umbilical scar, and another one passing the superior border, creating a safety area (Fig. 22.5).

If there is too much skin tension we can change our surgical plan, closing the umbilical scar and stretching it to the suprapubic region, leaving a small 2–3 cm longer vertical scar as a release tension maneuver (Fig. 22.6).

All the measurements are checked and tattooed in the key points with methylene blue ink.

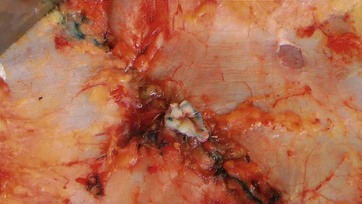

Following this, the skin and fat will be cut inferiorly and in the superior line below the umbilical scar, forming a flap that will be removed as a block, preserving the safety area (Fig. 22.7).

The umbilical scar is incised in its border. The undermining of the central portion of superior abdomen reaches the xiphoid, making a tunnel (Fig. 22.8).

The umbilical flap will be fixed in the aponeurosis in a triangular superior base shape (Fig. 22.9).

The flap will be sutured to the inferior border with temporary stitches and the incision for a new umbilical placement will be pointed using Pitanguy’s demarcator (Fig. 22.10).

Baroudi’s quilting sutures are performed with absorbable sutures, fixing the entire flap to the aponeurosis (Fig. 22.11).

Finally the umbilical skin, already fixed to the aponeurosis, is sutured to the abdominal skin.

Baroudi’s quilting sutures are finished, the remaining skin will be resected or not, depending on the level of tension (Fig. 22.12).

The flap will be sutured in three anatomical levels, finishing with a nonabsorbable intracutaneous tread, which stays in place for 20 or 30 days (Fig. 22.13). The use of a vacuum drain is routine although the liquid volume has been negligible. The sutures are covered with adhesive strips, the umbilical scar is filled with gauze and special foam is applied under a close fitting compression garment (Fig. 22.14).

Comments and Conclusion

The use of adequate postoperative garments, special foam, and compression stockings, together with lymphatic drainage and ultrasound therapy, makes the recovery time fast and comfortable. See Figs 22.15–22.20 for outcomes.

1 Kelly HA. Report of gynecological cases. Johns Hopkins Hosp Bull. 1899;10:197.

2 Callia WEP. Contribuição para o estudo da correção cirúrgica do abdome pêndulo e globoso – técnica original. São Paulo: Tese de Doutoramento apresentada à Faculdade de Medicina da USP; 1963.

3 Pitanguy I. Evaluation of body contouring surgery today: a 30 year perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1499.

4 Pontes R. Abdominoplastia, 1st ed. Revinter: Rio de Janeiro; 2004.

5 Baroudi R, Ferreira CAA. Seroma: how to avoid it and how to treat it. Aesth Surg J. 1988;18:439.

6 Avelar JM. Abdominoplasty: A new technique without undermining and fat layer removal. Arq Catarin Med. 2000;29:147–149.

7 Matarasso A, Swift RW, Rankin M. Abdominoplasty and abdominal contour surgery: a national plastic surgery survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;47:1797–1808.

8 Lockwood TE. Lower body lift with superficial fascial system suspension. Aesth Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:112.

9 Guerrero Santos J. Some problems and solutions in abdominoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 1980;4:227.

10 El-Mrakby HH, Milner RH. The vascular anatomy of the lower anterior abdominal wall: A micro dissection study on the deep inferior epigastric vessels and the perforator branches. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:539–547.

11 Boyd JB, Taylor GI, Corlett RJ. The vascular territories of the superior epigastric and the deep inferior epigastric systems. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:1–14.

12 Pitanguy I, Salgado F, Murakami R, et al. Abdominoplasty: classification and surgical techniques. Rev Bras Cir. 1995;85(1):23.

13 Bozola AR. Abdominoplasty: same classification and a new treatment concept 20 years later. Aesth Plast Surg. 2010;34(2):181–192.

14 Illouz YG. Une nouvelle technique pour les lipodystrophies localisées. Rev Chir Esthét Lang Franç. 1980;6:19.

15 Saldanha OR, Souza Pinto EB, Matos WM, et al. Lipoabdominoplasty with selective and safe undermining. Aesth Plast Surg. 2003;27:322–327.

16 Hunstad JP, Repta R. Atlas of abdominoplasty. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

17 Klein JA. Tumescent technique for liposuction surgery. Am J Cosmetic Surg. 1987;4:263.