Ligneous Conjunctivitis

Introduction

The first description of ligneous conjunctivitis appeared in 1847, with Bouisson1 describing a 46-year-old man with bilateral pseudomembranous conjunctivitis. In 1933, the term ‘ligneous,’ meaning ‘woody,’ was introduced by Borel2 to describe the characteristic wood-like consistency of the pseudomembranes. However, the link between ligneous conjunctivitis and plasminogen deficiency was not established until 1997 by Mingers et al.3 As many patients develop similar pseudomembranes in other mucous membranes of the body, Mingers et al.3 suggested the term ‘pseudomembranous disease’ to describe the systemic nature of this disease. Although the lesions have been referred to as pseudomembranous in the literature, the lesions are actually true membranes, as they bleed upon removal. It is characterized by multiple recurrences after local excision, and management involves the adjunctive use of topical and systemic replacement of plasminogen.

Epidemiology

Ligneous conjunctivitis is rare, and the prevalence of this disorder has not been firmly established. Ligneous conjunctivitis, associated with plasminogen deficiency is typically an autosomal recessive disorder that results from a homozygous or compound heterozygous defect. A study of 9611 blood donors in Scotland revealed a prevalence of 2.9 per 1000 heterozygous type I plasminogen deficiency subjects.4 The theoretical prevalence of homozygotes or compound heterozygotes has been calculated in the range of 1.6 per 1 million people.5 Females appear to be affected more than males, with a ratio of 1.27 : 1 to 1.39 : 1.5,6

The largest study of patients with severe type I plasminogen deficiency included 50 patients.6 The median age of clinical presentation was 9.75 months (range, 3 days to 61 years), demonstrating that ligneous conjunctivitis can occur in older individuals, despite it being classically associated with infants and children. The most common manifestation in this group was ligneous conjunctivitis (80%), followed by ligneous gingivitis (34%), with 14% of patients suffering from both. Less common extraocular manifestations included involvement of the ears, upper and lower respiratory tract (sinus, larynx, bronchi, lungs; 30%), the female genital tract (8%), the gastrointestinal tract (duodenal ulcer; 2%), congenital occlusive hydrocephalus (8%), and juvenile colloid milium of the skin (2%). Two of the patients with congenital occlusive hydrocephalus had Dandy–Walker malformation. Several studies have shown extraocular manifestations of severe plasminogen deficiency without ocular involvement.5,6

Etiology

There has been definitive evidence to support that ligneous conjunctivitis is the result of plasminogen deficiency.7–10 The case of ligneous conjunctivitis reported by Mingers et al. was also the first report of plasminogen deficiency in humans.3 There are two types of plasminogen deficiency: type I (hypoplasminogenemia) is a quantitative deficiency and type II (dysplasminogenemia) is a qualitative deficiency. Type I deficiency is the type most associated with ligneous conjunctivitis. Development of ligneous lesions is most commonly caused by sporadic mutations in the plasminogen gene; however, compound-heterozygous or homozygous mutations have been reported.3,5,6,9,10 Tefs et al. found the K19E mutation to be the most common genetic cause of type I plasminogen deficiency (34%) in a series of 50 patients.6 Knowledge of the genetics of the disease allows for prenatal diagnosis in known carrier families, which can be crucial in cases of obstructive congenital hydrocephalus.11

Plasmin is a serine protease and is the predominant fibrinolytic enzyme in the human circulation, it is also found in the extracellular matrix.12 Plasminogen is converted to plasmin by plasminogen activators in the blood.

Plasmin plays an important role in hemostasis as well as being an integral component of wound healing in its role in degrading fibrin. The gene for plasminogen is located on chromosome 6, and is produced predominantly by the liver. With plasminogen deficiency, wound-healing capability is diminished and is most pronounced in mucous membranes, such as the conjunctiva.12 The impaired wound-healing capacity causes an arrest at the stage of granulation tissue formation and excessive fibrin deposition. Thus, fibrin-rich membranes or mucus strands accumulate, stimulating inflammatory cells and fibroblasts, while desiccation of the fibrin leads to the ligneous consistency of the conjunctival lesions. Similar pathophysiologic mechanisms occur in extraocular manifestations of plasminogen deficiency.

While in extravascular spaces, fibrinolysis with low to nonexistent levels of plasminogen activity is impaired. However, intravascularly this is not the case, as can be inferred from the fact that thrombotic phenomena are absent in patients with ligneous conjunctivitis and plasminogen deficiency. It has been suggested that nonplasmin-induced fibrinolysis is intensified in patients with plasminogen deficiency and ligneous conjunctivitis, through elevated polymorphonuclear elastase levels, among other factors.10

Due to the appearance, histopathology, clinical course, and response to treatment, the authors also believe that ligneous conjunctivitis results from an exaggerated inflammatory response to tissue injury. This injury may arise from infection or physical trauma, including surgery. These factors may incite a genetic predisposition, such as plasminogen deficiency to develop this response. Schuster and Seregard also postulated that conjunctivitis is the most common manifestation of plasminogen deficiency, due to frequent exposure to ocular irritants.5 These irritants may start or perpetuate local inflammation and create ligneous membranes. Many cases of antecedent viral or bacterial infections have been described in the literature, including staphylococcal, streptococcal, and Haemophilus conjunctivitis.13–15 In these cases, it appears that ligneous conjunctivitis in genetically susceptible individuals develops as an abnormal response to the conjunctival trauma elicited by the infecting organisms.

Trauma, especially from surgery, is also thought to be a cause of ligneous conjunctivitis. The authors have reported a case of a 24-year-old woman with ligneous conjunctivitis of the left upper eyelid, who underwent a conjunctival autograft from her left lower to left upper eyelid. Ligneous conjunctivitis subsequently developed at the previously unaffected donor site and became resistant to treatment in the original site of disease in the palpebral conjunctiva of the upper lid.16 Later studies reported the same negative experience in previously unaffected fellow eyes.17 In these cases, ligneous conjunctivitis appears to develop as an abnormal response of the immune system to the conjunctival trauma.

Pathophysiology/Histopathology

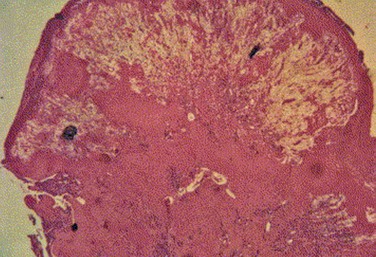

Histologic examination of ligneous membranes shows superficial or subepithelial deposits of eosinophilic amorphous hyaline, amyloid-like material with a variable proportion of granulation tissue with accompanying inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells, and granulocytes) (Fig. 24.1).5 This amorphous hyaline-like material has been shown to contain mainly fibrin and other plasma proteins, such as albumin and immunoglobulins (mainly IgG).5 Ligneous lesions may also contain variable amounts of mucopolysaccharides in adjacent granulation tissue.5 Abnormal vascular permeability has also been suggested as the source of the various components of the ligneous lesion. Melikian postulated that a serofibrinous transudate from the conjunctival neovascularization undergoes subsequent coagulation, with the resulting formation of granulation tissue and accumulation of the hyaline material, which becomes hardened in forming the ligneous membranes.18

Immunohistochemical evaluation of ligneous conjunctivitis lesions was first performed in 1988.19 In this study, a cellular infiltrate was seen that was composed mainly of T lymphocytes, which was seen again in later studies.17 The ratio of T-helper/inducer : T-suppressor/cytotoxic cells was approximately 3 : 1. Immunofluorescent techniques demonstrated that the major components of the hyaline material in the substantia propria were immunoglobulins. IgG was the most prominent, with staining for both light and heavy chains, but primarily for κ-light chains.

Topical cyclosporine A has been reported to be more effective than other topical agents (short of plasminogen preparations) in the treatment of this disorder in several studies.15,16,19 Cyclosporine A interferes with IL-2 production, therefore, preventing the activation and recruitment of the T-cell response. Immunohistochemical analysis of a lesion resected after 6 months of topical cyclosporine A therapy, supports the immune role of this entity.19 A significant decrease in the total number of T lymphocytes was found, with the greatest decrease occurring in the T-suppressor/cytotoxic cell subpopulation. Also of interest was the absence of IL-2 receptors on the T cells. Finally, a decrease in the number of B lymphocytes and plasma cells occurred. These results indicate the local effect of cyclosporine A on the immune response. The marked reduction of T-suppressor/cytotoxic cells was a secondary effect, as these cells are recruited by activated T cells. The clinical response and histopathologic confirmation of the effect of cyclosporine A further support the inflammatory nature of this disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ligneous conjunctivitis is based on the clinical picture (ocular and/or extraocular membranous lesions), the typical histological findings, and a possible positive family history. In most patients with ligneous conjunctivitis, hypoplasminogenemia may be found.5 In the report of Tefs et al. of 50 patients with plasminogen deficiency, plasminogen activity ranged from 4% to 51%.6 If the responsible mutation has been identified in an affected family, then prenatal diagnosis of children at risk is possible.5

Clinical Findings

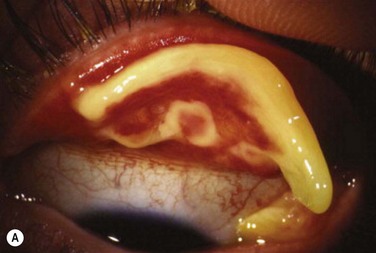

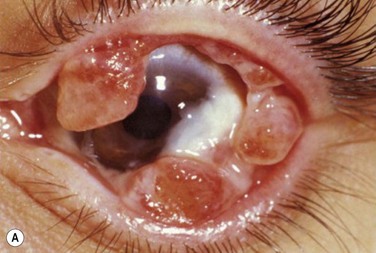

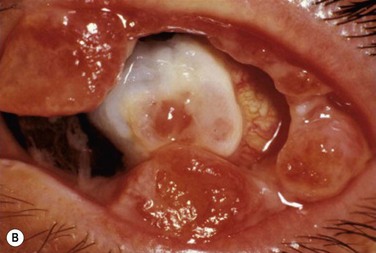

Patients typically present with a chronic conjunctivitis. Discharge or membranes are not seen in the early stages. The earliest true ligneous lesion appears as a highly vascularized, raised, friable lesion. This lesion can be removed easily with forceps, although it tends to bleed on removal. With continued inflammation, a white, thickened, avascular mass appears above the neovascular membrane (Fig. 24.2). Attempts at removal of this lesion without appropriate antiinflammatory therapy, often results in recurrence of the lesion to its original size within days. These lesions are most often seen on the palpebral conjunctiva of the upper and lower lids but may also be found on the bulbar conjunctiva, including the limbus. Bulbar conjunctival involvement may occur either from extension of a palpebral lesion or de novo. Limbal lesions may extend over the surface of the cornea and, in the most severe cases, lead to corneal neovascularization and scarring. Corneal involvement occurs in 26–30% of cases.5 From time to time, despite appropriate therapy, inflammation continues, and the chronic lesions become thickened, vascularized, and firm, giving rise to the name ‘ligneous,’ meaning woody.

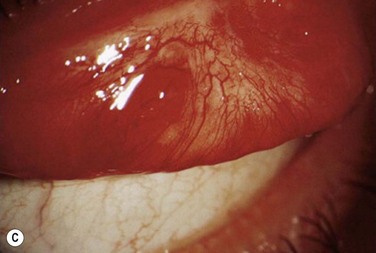

Early in the course of the disease, patients may complain of chronic tearing, mild discomfort, and redness. As the lesions grow, almost all patients complain of pain and photophobia. Severe cases result in almost constant discomfort, making it difficult for patients to carry out activities of daily living. The more severe lesions may extend beyond the lid margin (Fig. 24.3). Bilateral involvement occurs in up to 51% of patients, with the duration of the disease reportedly ranging from a few months to 44 years.5

Systemic Features

Fever or infections of the upper respiratory tract, urinary tract, or female genital tract, may either precede or concomitantly occur with ligneous conjunctivitis, or might even act as a trigger for the development of membranes.5

Orophayrnx

The second most frequently affect site is the mouth, with 34% of patients suffering from this in the largest series of patients with severe type 1 plasminogen deficiency.6 Painless nodular ulcerations or gingival hyperplasia occurs, often resulting in the loss of dental integrity.12 Similar membranous lesions may occur in the middle and tympanic membrane, causing chronic otitis media and fluctuating hearing loss.5

Respiratory Tract

Less frequently, ligneous lesions may develop in the larynx, vocal cords, and tracheobronchial tree. This may cause voice change (dysphonia), recurrent pneumonia, and potentially life-threatening airway obstruction. Recurrent tracheobronchial obstruction by ligneous masses is difficult to manage, and is associated with a poor prognosis.5

Genitourinary Tract

Ligneous lesions occurring in the female genital tract have most commonly been reported affecting the cervix, causing ligneous cervicitis.20 Lesions may also involve the vagina, fallopian tubes, ovary, and endometrium. Dysmenorrhea is the most common presenting symptom, and infertility may occur.20

Membranous plaques have been reported in the renal collecting system of two siblings with ligneous conjunctivitis.9 However, involvement of the renal tract appears to be a rare event in patients with ligneous conjunctivitis.5

Juvenile Colloid Milium

This is a rare skin condition characterized by the development of small, yellow-brown, translucent papules, typically in sun-exposed areas of the skin.5 In most cases, it is reported to occur after severe sunburn or chronic sun exposure, and tends to occur prior to puberty. It has been described to be associated with ligneous conjunctivitis.5

Management

Plasminogen substitution is presently being investigated as the primary treatment for ligneous conjunctivitis.3,7,10,21,22 Mingers et al. first proposed the theory of plasminogen deficiency and attempted supplementing plasminogen.3 Higher doses of intravenous lysine-conjugated plasminogen (1000 units/day, continuous infusion for 2 weeks) have been used successfully in an infant with ligneous conjunctivitis, followed by 2000-unit second daily bolus injections for 2 weeks, and then 1000-unit daily bolus injections long term.21 Topical plasminogen preparations extracted from fresh frozen plasma, have successfully been employed in the treatment of ligneous conjunctivitis: three patients remained free of recurrences for over 12 months, with topical administration as frequently as every 2 hours.7 Another patient with hourly plasminogen drop administration had resolution of pseudomembranes in 3 weeks: after tapering, the disease reoccurred and was again quieted with re-administration of plasminogen drops. Chronic low-dose maintenance treatment with topical plasminogen was thought necessary for this patient.22

A combination of systemic or subconjuctival fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and topical FFP have shown success in three patients.23–25 Using FFP bypasses, the need for plasminogen concentrate alone, which has a very short half-life and is difficult to have readily available. No reoccurrence of disease was noted 12 months after pseudomembrane excision in the first two studies, and after 10 months of follow-ups in the third study. A Japanese study successfully treated a 71-year-old and her elder sister with ligneous conjunctivitis, after ocular surgery with a combination of a direct thrombin inhibitor, topical Argatroban, and topical plasma obtained from their healthy family members.26

Based on the early observations of the presence of granulation tissue and inflammatory cells in ligneous tissue, topical medical regimens geared toward these non-specific findings were developed. Topical therapy, including topical hyaluronidase, alpha-chymotrypsin, sodium cromoglycate, antibiotics, corticosteroids, and fibrinolysin, have met with limited success.5 Heparin has been reported to have partial success in controlling ligneous conjunctivitis.27,28 De Cock et al.27 treated 17 patients with ligneous conjunctivitis with local excision and immediate, perioperative topical treatment, with intensive heparin and corticosteroids, and in 12 patients additional alpha-chymotrypsin. Overall, 13 of the 17 patients were successfully controlled with this regimen.27 Cyclosporine had been the most promising element in the therapeutic armamentarium before plasminogen.15,29 Recently, oral contraceptives have been noted to show a marked increase in plasminogen levels, due to hormonal up-regulation of plasminogen synthesis. In two patients, Sartori et al. showed treatment to be associated with a rise in plasminogen levels and improvement in clinical findings with resolution of disease in one patient.30 This therapy may be useful in selected female patients with hypoplasminogenemia. Finally, an anecdotal report by Lee and Himmel described successful resolution of a recurrent case of ligneous conjunctivitis with allogeneic serum tears from a family member, confirmed to have normal plasminogen levels.31 This source of plasminogen may be useful if fresh frozen plasma is not readily available, only after the family member has been cleared of potential blood-borne infectious disease transmission.

Because trauma to the conjunctiva is likely to be an etiologic factor in ligneous conjunctivitis, conjunctival surgery must be performed only with the utmost care. The authors recommend against performing conjunctival autograft for ligneous conjunctivitis. Barabino and Rolando performed amniotic membrane transplantation for conjunctival reconstruction of ligneous conjunctivitis.32 Following surgery, the patient was given a 6-month course of heparin eye drops (5000 U/mL) with dexamethasone and tobramycin for 2 weeks postoperatively. The patient had small recurrences at 8 months, necessitating regrafting of the amniotic membrane. At 36 months post-procedure, the patient was disease free. The authors would advise pretreating any patient with plasminogen therapy prior to surgery, with slow postoperative tapering. Otherwise, cryosurgery, electrocoagulation, and surgical resection of ligneous lesions, typically result in rapid recurrence of the lesions within days to weeks.

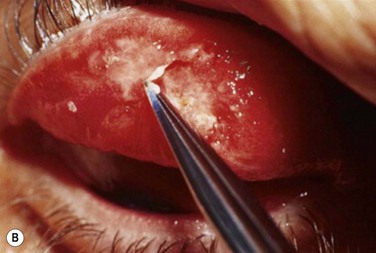

Early in the postoperative period, patients must be seen at least once a day. A small but significant amount of recurrence will be seen daily in every patient, and every recurrent lesion must be debrided daily with a jeweler’s forceps (Fig. 24.4). If abnormal tissue is allowed to collect for even 1 to 2 days, it will act as a barrier and prevent the topical medications from reaching the basal tissue, which is the origin of the ligneous membranes. Pediatric patients are restrained for their daily examinations, and their parents are taught to debride the lesions with cotton-tipped applicators while they are applying the eye drops.

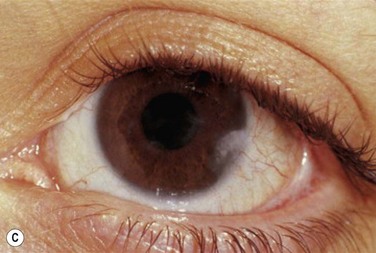

Within the first few weeks of therapy, the rate and severity of recurrences lessen and the topical medications can be tapered slowly. Some lesions progress despite this aggressive topical therapy. Patients with these lesions must be brought back to the operating room for repeat excisional biopsy. After this surgical procedure, the patient must be placed back on the initial topical regimen, described previously. Results with repeated excisions and aggressive topical management have been satisfactory (Fig. 24.5). As we continue to refine plasminogen therapy, more light is being shed on the pathophysiology of this disease. Overall, the development of systemic and topical plasminogen preparations, as a treatment of ligneous conjunctivitis, carries a new promise for patients with ligneous conjunctivitis.

References

1. Bouisson, M. Ophthalmie sur-aigue avec formation de pseudomembranes à la surface de la conjonctive. Ann Ocul. 1847;17:100–104.

2. Borel, MG. Un nouveau syndrome palpebral. Bull Soc Fr Ophthalmol. 1933;46:168–180.

3. Mingers, AM, Heimburger, N, Zeitler, P, et al. Homozygous type I plasminogen deficiency. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1997;23:259–269.

4. Tait, RC, Walker, ID, Conkie, JA, et al. Isolated familial plasminogen deficiency may not be a risk factor for thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 1996;76:1004–1008.

5. Schuster, V, Seregard, S. Ligneous conjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:369–388.

6. Tefs, K, Gueorguieva, M, Klammt, J, et al. Molecular and clinical spectrum of type I plasminogen deficiency: a series of 50 patients. Blood. 2006;108:3021–3026.

7. Watts, P, Suresh, P, Mezer, E, et al. Effective treatment of ligneous conjunctivitis with topical plasminogen. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:451–455.

8. Ramsby, ML, Donshik, PC, Makowski, GS. Ligneous conjunctivitis: biochemical evidence for hypofibrinolysis. Inflammation. 2000;24:45–71.

9. Schuster, V, Seidenspinner, S, Zeitler, P, et al. Compound-heterozygous mutations in the plasminogen gene predispose to the development of ligneous conjunctivitis. Blood. 1999;93:3457–3466.

10. Mingers, AM, Philapitsch, A, Schwarz, HP, et al. Polymorphonuclear elastase in patients with homozygous type I plasminogen deficiency and ligneous conjunctivitis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1998;24:605–612.

11. Schuster, V, Seidenspinner, S, Muller, C, et al. Prenatal diagnosis in a family with severe type I plasminogen deficiency, ligneous conjunctivitis and congenital hydrocephalus. Prenat Diagn. 1999;19:483–487.

12. Mehta, R, Shapiro, AD. Plasminogen deficiency. Haemophilia. 2008;14:1261–1268.

13. Chambers, JD, Blodi, FC, Golden, B, et al. Ligneous conjunctivitis. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1969;73:996–1004.

14. Newcomer, V, Klein, A. Ligneous conjunctivitis. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:511–512.

15. Rubin, BI, Holland, EJ, de Smet, MD, et al. Response of reactivated ligneous conjunctivitis to topical cyclosporine. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:95–96.

16. Schwartz, GS, Holland, EJ. Induction of ligneous conjunctivitis by conjunctival surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:253–254.

17. Rao, SK, Biswas, J, Rajagopal, R, et al. Ligneous conjunctivitis: a clinicopathologic study of 3 cases. Int Ophthalmol. 1998;22:201–206.

18. Melikian, HE. Treatment of ligneous conjunctivitis. Ann Ophthalmol. 1985;17:763–765.

19. Holland, EJ, Chan, CC, Kuwabara, T, et al. Immunohistologic findings and results of treatment with cyclosporine in ligneous conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:160–166.

20. Pantanowitz, L. Ligneous conjunctivitis. BJOG. 2004;111:635.

21. Schott, D, Dempfle, CE, Beck, P, et al. Therapy with a purified plasminogen concentrate in an infant with ligneous conjunctivitis and homozygous plasminogen deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1679–1686.

22. Heidemann, DG, Williams, GA, Hartzer, M, et al. Treatment of ligneous conjunctivitis with topical plasmin and topical plasminogen. Cornea. 2003;22:760–762.

23. Gürlü, VP, Demir, M, Alimgil, ML, et al. Systemic and topical fresh-frozen plasma treatment in a newborn with ligneous conjunctivitis. Cornea. 2008;27:501–503.

24. Tabbara, KF. Prevention of ligneous conjunctivitis by topical and subconjunctival fresh frozen plasma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:299–300.

25. Pergantou, H, Likaki, D, Fotopoulou, M, et al. Management of ligneous conjunctivitis in a child with plasminogen deficiency. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:1333–1336.

26. Suzuki, T, Ikewaki, J, Iwata, H, et al. The first two Japanese cases of severe type I congenital plasminogen deficiency with ligneous conjunctivitis: successful treatment with direct thrombin inhibitor and fresh plasma. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:363–365.

27. De Cock, R, Ficker, LA, Dart, JG, et al. Topical heparin in the treatment of ligneous conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1654–1659.

28. Hiremath, M, Elder, J, Newall, F, et al. Heparin in the long-term management of ligneous conjunctivitis: a case report and review of literature. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2011;22:606–609.

29. Holland, EJ, Olsen, TW, Ketcham, JM, et al. Topical cyclosporin A in the treatment of anterior segment inflammatory disease. Cornea. 1993;12:413–419.

30. Sartori, TM, Saggiorato, G, Pellati, D, et al. Contraceptive pills induce an improvement in congenital hypoplasminogenemia in two unrelated patients with ligneous conjunctivitis. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:86–91.

31. Lee, WB, Himmel, K. Allogeneic serum drops for the treatment of ligneous conjunctivitis. Cornea. 2008;28:122–123.

32. Barabino, S, Rolando, M. Amniotic membrane transplantation in a case of ligneous conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:752–753.