LIGHTNING STRIKE

Lightning strikes the earth at least 100 times per second during an estimated 3,000 thunderstorms per day. Fortunately, the odds of being struck by lightning are not very great. Still, approximately 60 persons per year are victims of fatal strikes in the United States. The wise traveler respects thunderstorms and seeks shelter at all times during a lightning storm.

Lightning can injure a person in five ways:

1. Direct hit, which most often occurs in the open.

2. Splash, which occurs when lightning hits another object (tree, building). The current seeks the path of least resistance, and may jump to a human. Splashes may occur from person to person, or from a metal fence.

3. Contact, when a person is holding on to a conductive material that is hit or splashed by lightning.

4. Step (stride) voltage (or ground current), when lightning hits the ground or an object nearby. The current spreads like waves in a pond.

5. Blunt injury, which occurs from the victim’s own muscle contractions and/or from the explosive force of the shock wave produced by the lightning strike. These can combine to cause the victim to be thrown, sometimes a considerable distance.

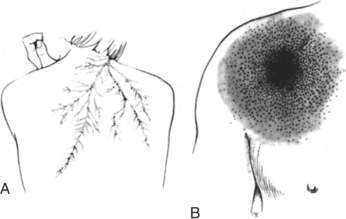

When lightning strikes a person directly, splashes at him from a tree or building, or is conducted along the ground, it usually largely flows around the outside of the body (flashover phenomenon), which causes a unique constellation of signs and symptoms. The victim is frequently thrown, clothes may be burned or torn (“exploded” off by the instantaneous conversion of sweat to steam), metallic objects (such as belt buckles) may be heated, and shoes removed. The victim often undergoes severe muscle contractions—sufficient to dislocate limbs. In most cases, the person struck is confused and rendered temporarily blind and/or deaf. In some cases, there are linear (1½ to 2 in, or 1.3 to 5 cm, wide, following areas of heavy sweat concentration), “feathered” (fernlike; keraunographism; Lichtenberg’s flowers—cutaneous imprints from electron showers that track over the skin) (Figure 215, A), or “sunburst” patterns of punctate burns over the skin (Figure 215, B), loss of consciousness, ruptured eardrums, and inability to breathe. Occasionally, the victim ceases breathing and suffers a cardiac arrest. Seizures or direct brain damage may occur. Eye injuries occur in half of victims.

A victim struck by lightning may not remember the flash or thunder, or even recognize that he has been hit. The confusion, muscle aches, body tingling, and amnesia can last for days. With a more severe case, the skin may be mottled, the legs and/or arms may be paralyzed, and it may be difficult to locate a pulse in the radial (wrist) artery (see page 33), because the muscles in the wall of the artery are in spasm. First-, second-, or third-degree skin burns may be present. Broken bones are not uncommon.

1. Maintain the airway and assist breathing (see page 29). Continue to perform artificial respiration and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) (see page 32) until sophisticated help can be obtained. Victims of lightning strike may have paralysis of the breathing mechanism for a period of 15 to 30 minutes, and then make a remarkable recovery. A seemingly lifeless individual may be saved if you breathe for him promptly after the injury. Do not assume that dilated or nonreactive (to light—see page 36) pupils are a sign of death, because they may represent direct injury to the eye(s).

2. Assume that the victim has been thrown a considerable distance. Protect the cervical spine (see page 37).

3. Examine the victim for any other injuries and treat accordingly.

4. Transport the victim to a hospital.

5. If you are in the vicinity of a thunderstorm, seek shelter for the victim and yourself. Lightning can strike twice in the same place!

LIGHTNING AVOIDANCE

1. Know the weather patterns for your area. Don’t travel in times of high thunderstorm risk. Avoid being outdoors during a thunderstorm. Carry a radio to monitor weather reports. Lightning can lash out from many miles in front of a storm cloud, in seemingly clear weather. If you calculate (see above) that a nearby lightning strike is within 3 miles (5 km) of your location, anticipate that the next strike will be in your immediate area. The “30-30 rule” specifies that if you see lightning and count less than 30 seconds before hearing thunder, seek shelter immediately. Since thunder is rarely heard from more than 10 miles away, if you hear thunder, it is best to curtail activities and seek shelter from lightning. Do not resume activities outdoors for at least 30 minutes after the lightning is seen and the last thunder heard.

2. If a storm enters your area, immediately seek shelter. Enter a hard-roofed auto or large building, if possible. Tents and convertible autos offer essentially no protection from lightning. Tent poles are lightning rods. Metal sheds are dangerous because of the risk of side splashes. Indoors, stay away from windows, open doors, fireplaces, and large metal fixtures. Inside a building, avoid plumbing fixtures, telephones, and other appliances attached by metal to the outside of the building.

3. Do not carry a lightning rod, such as a fishing pole or golf club. Avoid tall objects, such as ski lifts and power lines. Avoid being near boat masts or flagpoles. Do not seek refuge near power lines or tall metal structures. If you are in a boat, try to get out of the water. If you are swimming in the water, get out. Do not stand near a metal boat. Insulate yourself from ground current by crouching on a sleeping pad, backpack, or coiled rope.

4. Move off ridges and summits. Thunderstorms tend to occur in the afternoon, so attempt to summit early and be heading back down by noon. In the woods, avoid the tallest trees (stay at a distance from the tree that’s at least equal to the tree’s height) or hilltops. Shelter yourself in a stand of smaller trees. Avoid clearings—you become the tallest tree. Don’t stay at or near the top of a peak or ridge. Avoid cave entrances. In the open, crouch down or roll into a ball.

5. Stay in your car. If it is a convertible, huddle on the ground at least 50 yards (46 m) from the vehicle.

6. If you are part of a group of people, spread the group out so that everyone isn’t struck by a single discharge.

7. If your hair stands on end, you hear high-pitched or crackling noises, or see a blue halo (St. Elmo’s fire) around objects, there is electrical activity near you that precedes a lightning strike. If you can’t get away from the area immediately, crouch down on the balls of your feet and keep your head down. Don’t touch the ground with your hands.

8. The StrikeAlert Personal Lightning Detector (Outdoor Technologies, Inc.) is the size and configuration of a pager and uses an audible warning and LED display to show the wearer how far away lightning is striking and if a storm is approaching or leaving.

TORNADO AVOIDANCE

1. Watch the cloud formations in a stormy sky. If you see revolving, funnel-shaped clouds, you are in danger.

2. Take shelter immediately. The best location is an underground cave or concrete structure. Do not remain in a tent or camper.

3. If you are caught outside in open country, hunker down or lie flat in a depression, ditch, culvert, or ravine. Cover your head with your arms.

4. Do not try to outrun a tornado. There is no way to predict when it will change direction.

WHAT TO DO IN AN EARTHQUAKE

If you are caught in an earthquake in a wilderness setting, do the following:

1. Seek a safe location, out of the path of a rockfall, mudslide, or snow avalanche. If you can, move into a clearing away from buildings, trees, and power lines. If the ground shaking is extreme, position yourself on your hands and knees.

2. Eliminate any obvious fire hazards. If you are in a cabin supplied with natural gas, turn it off at the source if there is any odor or you believe there might be a leak.

3. Be prepared for aftershocks.

4. Secure a supply of drinking water. Be certain that you are prepared for a period of time without electrical power.

5. Prepare a shelter, store sufficient food, and locate equipment necessary for survival. Keep first-aid supplies and a flashlight within easy reach.

VOLCANOES

What to Do if Working or Traveling Near an Active Volcano

1. To learn the volcano’s pattern of eruption, read about past eruptions and accidents.

2. Know the current volcano warning level. Obey local authorities.

3. Travel with an experienced guide.

4. Leave details about your itinerary with someone who can report you as delayed or missing.

5. Wear a hardhat and carry a gas mask.

6. Beware of rockfall, avalanche, and hazardous gases.

7. Observe for warning signs of an eruption. Leave immediately if the area becomes dangerous.

SNOW AVALANCHES

A completely buried victim has a poor chance of survival. Survival is interrelated with both time and depth of burial. Survival probabilities diminish with increasing burial depth. To date, no one in the United States who has been buried deeper than 7 ft (2.1 m) has been recovered alive.