CHAPTER 2 LIFESTYLE

DIET OR MEDICAL NUTRITIONAL THERAPY

GOALS OF MEDICAL NUTRITIONAL THERAPY IN TYPE 2 DIABETES MELLITUS

ASSESSMENT OF DIET

A nutritional assessment might include information about the following:

BASIC DIETARY RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2003 Diabetes UK issued a comprehensive list of consensus-based recommendations for diabetics that drew upon many sources to provide detailed practical advice for professionals to implement (Connor et al 2003). These are summarised in Table 2.1. The American Diabetes Association has also published its recommendations in its annually updated guidance.

TABLE 2.1 Summary of recommendations for a diabetes diet–based upon Diabetes UK 2003 (Connor et al 2003) and ADA position statement (ADA 2007)

| Component | Comments |

|---|---|

| Protein | Not > 1 g per kg body weight (different for nephropathy and children) |

| Total fat | < 35% of energy intake |

| Saturated + transunsaturated fat | < 7% of energy intake with trans fat intake minimised |

| n-6 polyunsaturated fat | < 10% of energy intake |

| n-3 polyunsaturated fat | Eat fish, especially oily fish, 1–2 times weekly |

| Fish oil supplements not recommended | |

| cis-monounsaturated fat* | 10–20% |

| Total carbohydrate* | 45–60% |

| Sucrose | Up to 10% of daily energy, eaten within the context of a healthy diet |

| Consider using non-nutritive sweeteners where appropriate if overweight and/or hypertriglyceridaemic | |

| Fibre | No quantitative recommendation |

| Soluble fibre has beneficial effects on glycaemic and lipid metabolism | |

| “Insoluble” fibre has no direct effects on glycaemic and lipid metabolism, but its high satiety content may help weight loss and is advantageous to gastrointestinal health | |

| Vitamins and antioxidants | Encourage foods naturally rich in vitamins and antioxidants |

| Supplements are usually not recommended (except in special circumstances) and some may be harmful | |

| Salt | < 6 g sodium chloride per day |

MODELS OF DIETARY ADVICE

DIETARY CARBOHYDRATE

The glycaemic response to foods can be affected by several factors:

Quantity of carbohydrate

http://www.leedsth.nhs.uk/sites/diabetes/food/CarbohydrateCountingRef.php

Type of carbohydrate

The terms sugars, starch and fibre are preferred to the terms simple sugars, complex and fast-acting carbohydrates, as the latter are not well defined. The glycaemic index (GI) has been devised to quantify the glycaemic effect of different foods. However, different methods of food processing and preparation, and ripeness in some cases, can alter the GI. Consuming food with a low GI has not been shown to improve glycaemic control in type 2 diabetics, but may improve the lipid profile. However, using the GI may provide additional benefit for glycaemic control beyond that observed for carbohydrate monitoring alone (ADA 2007).

Fibre-containing foods, such as whole grains, fruit and vegetables, provide vitamins, minerals and other important substances, and should be included in the diet. However, very large amounts of fibre would need to be consumed to produce metabolic improvements on glycaemia and lipid profiles. Sucrose or sucrose-containing foods should not be restricted for diabetics, but can be used in substitution for other carbohydrate sources.

DIETARY FAT

Both Diabetes UK (Connor et al 2003) and the National Cholesterol Education Program (Expert Panel 2001) recommend that the total fat should not exceed 35% of the total energy intake. The most important dietary modification is to reduce the intake of saturated fat, the principal dietary determinant of serum LDL-cholesterol levels; saturated and transunsaturated fat should provide less than 7% (ADA 2007) or 10% (Connor et al 2003) of energy. Unfortunately, in most European countries, current intake of saturated fat is above the recommended maximum 10% of total energy intake.

CHROMIUM

There is still “insufficient evidence to support any of the proposed health claims for chromium supplementation” (ADA 2007).

ALCOHOLIC DRINKS

The standard advice is: to stay within the recommended limits and to avoid drinking on an empty stomach (risk of significant hypoglycaemia) or as a substitute for a meal. In type 2 diabetics, drinking two to three glasses of wine (or the equivalent quantity of beer) may produce an insignificant drop in blood glucose, but does not increase the risk of hypoglycaemia (Christiansen et al 1996). Alcohol is potentially a major energy source, but it can contribute to elevated blood pressure and serum triglycerides.

OTHER CIRCUMSTANCES

Hypertension

There are a number of dietary modifications that can contribute to lowering blood pressure:

The American Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) is an eating plan that advises hypertensive individuals to consume a diet rich in fruit, vegetables and low-fat dairy products with a reduced content of saturated and total fat. Those who follow this diet combined with sodium restriction can expect to their lower systolic blood pressure by 8 to 14 mmHg (Sacks et al 2001). The eating plan can be downloaded off the internet.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND EXERCISE

DEFINITIONS

Exercise is a type of physical activity that is carried out to enhance or maintain an aspect of fitness.

RATIONALE

A sedentary lifestyle is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). Sedentary individuals are more likely to be obese and have adverse lipid profiles. In one study that recruited diabetic women, those undertaking less than 1 hour per week or no physical activity doubled their risk of having a cardiovascular event, compared to those undertaking at least 7 hours per week of physical activity (Hu et al 2001). Another study that recruited diabetic men found that “low” baseline cardio-respiratory fitness nearly trebled overall mortality compared with “moderate” or “high” fitness, and overall mortality nearly doubled in those reporting no recreational exercise in the previous 3 months, compared to those reporting any recreational physical activity in the same period (Wei et al 2000).

There is no current evidence to demonstrate a direct relationship between levels of physical activity and the development of the macrovascular and microvascular complications of diabetes. The arguments in favour of increased physical activity are based upon extrapolation from the effect of exercise on glycaemia. A recent report by the Chief Medical Officer distinguishes between the preventive effects (which appear to be strong) and the therapeutic effects of physical activity in type 2 diabetics (Department of Health 2004). The key message is that “the correct type of exercise is good”.

Exercise has both short- and long-term benefits in type 2 patients (see Table 2.2). Exercise can be an effective way to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Pierce 1999): an appropriate level of physical activity, particularly in conjunction with diet, can improve cardiovascular risk factors, such as blood pressure, weight and lipids. A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 RCTs “showed that exercise … improves glycaemic control and reduces visceral adipose tissue and plasma triglycerides, but not plasma cholesterol, … even without weight loss” (Thomas et al 2006).

TABLE 2.2 The benefits of exercise for type 2 patients (ADA 1995, Buckley et al 1999)

| Metabolic: |

| Reduced short-term insulin resistance; long-term effect has yet to be established |

| Increased peripheral glucose uptake |

| Less atherogenic profile (decreased triglycerides and LDL cholesterol with a beneficial increase in HDL cholesterol) |

| There is still no clear consensus on whether physical training results in improved fibrinolytic activity, which is impaired in type 2 diabetics |

| Reduces hypertension, particularly when hyperinsulinaemia is present |

| Helps to maintain muscle mass and promote preferentially the loss of adipose tissue, which may reduce the fall in metabolic rate during slimming and accelerate long-term weight loss |

| Favours weight loss by increasing energy expenditure (although an ageing overweight type 2 diabetic will be hard pressed to maintain the necessary daily level of exercise), in combination with a “slimming” diet |

Prevention: physical activity undertaken in early adult life protects against the subsequent development of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged men and women (Ha & Lean 1997) and in patients with impaired glucose tolerance (Tuomilehto et al 2001)

TARGETS

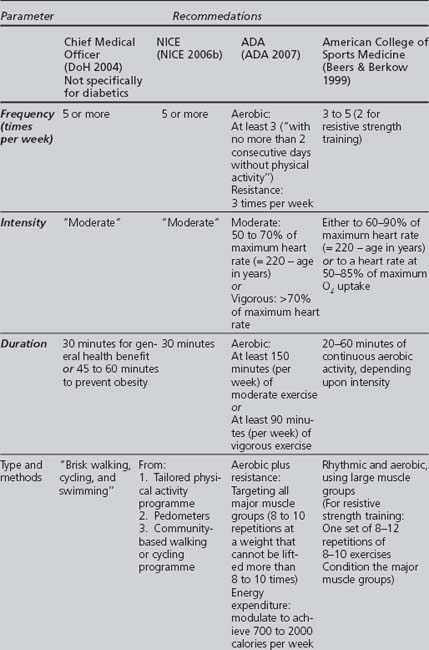

Published guidelines give criteria for the intensity, type, frequency and duration of physical activity that should be fulfilled in an exercise programme for diabetics. Some of the more important guidelines are summarised in Table 2.3.

EVALUATION PRIOR TO UNDERTAKING AN EXERCISE PROGRAMME

Prior to beginning an exercise programme, a diabetic needs to be assessed for the following:

INTERVENTIONS

The recommendations of different authoritative bodies list several criteria that a suitable exercise programme for patients with diabetes should fulfil, summarised in Table 2.3. Most recommend that exercise should be:

NICE’s options for increased physical activity include approved exercise referral schemes, use of pedometers, and walking and cycling schemes. However, it does admit that there is “insufficient evidence to recommend the use of pedometers and walking and cycling schemes to promote physical activity, other than as part of research studies where effectiveness can be evaluated” (NICE 2006b).

The “ideal” may not be desirable or realistic for all diabetics. In any exercise programme, essential precautions are the inclusion of proper warm up and cooling down, suitable foot care, and adequate hydration and metabolic control (Ruderman et al 2002).

There are a number of exercise schemes that may be accessible and suitable for diabetics:

Further information about Quality Assurance for exercise programmes is on the Department of Health’s website (http://www.dh.gov.uk). An American perspective is given in the Surgeon General’s report on Physical Activity and Health (US Department of Health 1996).

Table 2.4 gives guidance about maintaining glycaemic control during exercise.

TABLE 2.4 Guidelines for a diabetic’s optimal glycaemic response to exercise

| Metabolic control before exercise |

SMOKING

RATIONALE

The UKPDS identified smoking as a risk factor for coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetics (Turner 1998). Smoking also promotes the development of microvascular complications of diabetes (retinopathy, nephropathy and foot disease).

Cigarette smoking increases cardiovascular risk by:

Although the main benefits of smoking cessation are the reduction of all-cause mortality and the development of CVD (CHD, stroke and especially PVD; Macleod 1994), there is evidence now emerging that patients with diabetes may be able to reduce their risk of developing some diabetes complications, such as nephropathy and neuropathy by giving up smoking.

It is a source of optimism that the proportion of the English population that smokes has declined. The latest Health Survey for England (NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre 2004) found that:

ASSESSMENT

If the patient is a current smoker, it is also useful to ascertain:

The above information may inform the professional’s choice of strategies to use that are mostly likely to promote smoking cessation. Any information elicited should be documented in the clinical records, including if a patient is reluctant to consider change or if any positive encouragement was given to an ex-smoker (NICE 2006a).

INTERVENTIONS

A variety of the available strategies to promote smoking cessation are effective (Lancaster et al 2000). In 2002 NICE recommended that both bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy should be funded by the NHS (NICE Appraisal Committee 2002).

A patient unwilling to consider the benefits of or how to initiate any action to make change is extremely unlikely to respond to any intervention. In such circumstances, all the professional can do is to briefly emphasise the positive health and social benefits of becoming a nonsmoker while underlining the considerable risks of remaining a smoker. Handled sensitively, “the door is left open” and, possibly, a useful idea is planted. In a cross-sectional household survey, nearly half of those who had quit smoking did so as an unplanned attempt: once the decision was made to quit, immediate action was taken without planning (West & Sohal 2006). Professionals need to recognise a patient’s level of motivation in order to target their interventions at those most likely to respond.

Advice

Brief focused interventions consisting of advice given by health professionals can achieve smoking cessation rates of 2% (University of York 1998) and may be the “key” to persuading more smokers to stop (West 2005). NICE has provided guidance on brief interventions by professionals to promote smoking cessation, recommending that these may take 5 to 10 minutes and should include one or more of the following:

NICE calculated that if professionals carried out the above, the smoking cessation rate could increase to 4.3% (NICE 2006).

There is evidence that counselling over the telephone is effective without face-to-face contact (Zhu et al 1996). When more “intensive” telephone counselling (using behavioural methods) is combined with NRT, smoking cessation rates are significantly higher (An et al 2006).

NICE guidance for prescribing smoking cessation aids

In its 2002 technology appraisal, NICE recommended that:

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)

There are over 50 RCTs comparing NRT against placebo in the Cochrane database. A Cochrane review found all of the commercially available forms of NRT to be effective as part of a strategy to promote smoking cessation. Compared to placebo, NRT doubled quit rates after 1 year in motivated patients. NRT effectiveness appears to be largely independent of the intensity of additional support provided to the smoker (Silagy et al 2004).

Antidepressants

The antidepressants bupropion (Zyban – see BNF section 4.10) and nortriptyline have increased smoking cessation rates in a small number of trials. Only some antidepressants aid smoking cessation independently of the presence of depressive symptoms, suggesting that their mode of action is not linked to their therapeutic antidepressant effect (Hughes et al 2004). Patients in these trials were offered also behavioural support; these drugs should be prescribed within a structured counselling programme (Lancaster et al 2000).

Other methods of smoking cessation

Other methods that have been used for smoking cessation are considered either ineffective (anxiolytics and lobeline), of uncertain benefit (acupuncture, aversion therapy, hypnotherapy), or limited by side effects (clonidine). It is possible that the cannabinoid receptor antagonist, rimonabant (discussed in Chapter 4), may have potential in aiding smoking cessation.

ALCOHOL

RATIONALE

There is an inverse relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of CHD mortality (Valmadrid et al 1999, Ajani et al 2000); however, moderate alcohol consumption may offer some protection against stroke (Sacco et al 1999). There are no data available on alcohol consumption and the risk of developing peripheral vascular disease (PVD). There is no evidence that alcohol is a risk factor for the development of diabetic neuropathy.

ASSESSMENT

Alcohol consumption is measured in units, with 1 unit equating to:

PATIENT EDUCATION AND LIFESTYLE MODIFICATION

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF THE PROCESS OF HEALTH EDUCATION

STRUCTURES AND PROCESSES FOR THE DELIVERY OF DIABETES EDUCATION

Background

NICE published a technology appraisal in 2003 of patient education models for diabetes. NICE defined structured education as “a planned and graded programme that is comprehensive in scope, flexible in content, responsive to an individual’s clinical and psychological needs, and adaptable to his or her educational and cultural background” (NICE 2003). Following this, a joint Diabetes UK and the Department of Health Patient Education Working Group published a report in 2005 highlighting best practice for a structured educational programme that can fulfil the requirements in the NICE definition (DoH, Diabetes UK 2005).

Structured educational programmes

Local adult education programmes are also being developed. A successful example is the Diabetes X-PERT Programme; a structured group education programme based upon the theories of empowerment and discovery learning. More information can be found on the programme’s website: www.xpert-diabetes.org.uk.

Types of educational interventions

Reviews of the evidence on the effectiveness of different interventions on modifying the lifestyle of diabetics have been carried out by SIGN (SIGN 2001), the University of Sheffield (McIntosh et al 2002), and the NICE technology appraisal (NICE 2003). NICE concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend a specific type of education or to provide guidance on the settings for and frequency of sessions. There are still substantial gaps, but there is a considerable volume of ongoing research, and it is hoped that the picture should become progressively clearer.

NICE’s suggestions for the principles of good practice include:

The different educational methods include:

A PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACH TO HEALTH EDUCATION CONSULTATIONS

A personal view

Patients often know more than is credited about their disease and other health matters. The priority of health education is more often to facilitate behavioural change than to simply “spoon feed” information. This requires an approach that is not didactic, but that does draw upon the working methods of educationalists and psychologists.

Effective consultation technique

Effective consultation behaviours in all patient contacts, without ignoring clinical issues, are more likely to facilitate changes in a patient’s behaviour. A review published in the BMJ provides a helpful list of concepts and techniques (Gask & Usherwood 2002), but there is a wealth of excellent literature (Launer 2002, Pendleton et al 2003).

“Successful” consultations are more likely to result if:

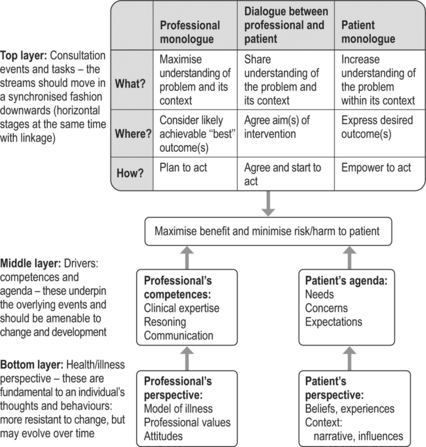

One of the authors (SL) has developed his own consultation model that aims to clarify behaviours within consultations more likely to produce beneficial outcomes (see Figure 2.1).

Educational triangle

The triad of “aims, methods and assessment” can also be applied to health education:

Models of change

Trans-theoretical model of change

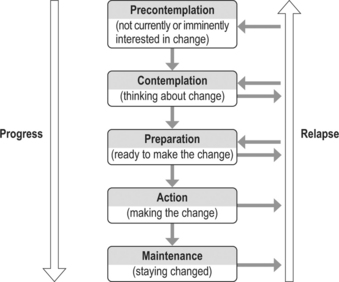

In the 1980s the “trans-theoretical model of change” for addiction behaviours was published (Prochaska & DiClemente 1992). Many professionals began to recognise that the model (summarised in Figure 2.2) could be applied to various health-related behaviours, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, diet and exercise. This model is particularly attractive because it recognises that different strategies are required to further change at each stage, and because it reflects the progress and relapse that occurs in real life.

Various triggers may cause a patient to move from being unwilling to being prepared to think about change. This transformation may result from realising that an adverse event may be imminent or more likely, that the problem is connected to current behaviour, and that the benefits of change outweigh the risks and/or disadvantages. If a patient appears unwilling to change, then the professional may wish to use one or more of the following strategies to help the patient move from the pre-contemplation to contemplation:

Model of change based upon the “catastrophe theory”

An alternative to the trans-theoretical model has been proposed recently. This is based on a branch of mathematics, where tensions develop in a system so that even small “triggers” can cause “catastrophic” changes. It is proposed “that beliefs, past experiences, and the current situation create varying levels of ‘motivational tension’, in the presence of which even quite small ‘triggers’ can lead to … renunciation.” If a plan for later action is the result, then this “may signify a lower level of commitment” in the individual (West & Sohal 2006).

West has incorporated this concept in a theory of motivation and how it can be applied to addictive behaviours (West 2006). He advises public health campaigns that seek to influence behaviours to focus on the “3 Ts”:

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and motivational approaches

Problem-solving

CBT has a wide range of established clinical applications, especially for mental health problems, such as depression, panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (Enright 1997). There is now increasing interest in using CBT to modify other behaviours. The CBT process can be divided into three sequential steps (that can be undertaken over several encounters):

Ask the patient to define his goals and to consider his “picture of health”; the patient can be helped to explore the benefits of change, with attention to the expected gains (physical, psychological, cognitive). Goal identification also defines when the intervention is completed.

Motivation

Simple questions can be asked to explore importance:

If the status of a patient’s motivational components are applied to the trans-theoretical model of change:

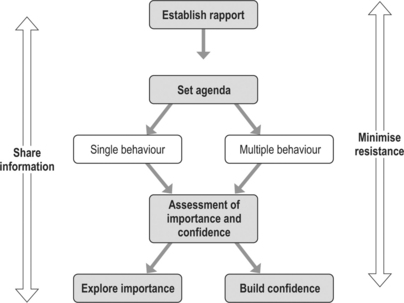

To facilitate a patient’s progress through the CBT process, the professional may wish to employ motivational interviewing techniques (summarised in Figure 2.3). Professionals can combine effective consulting techniques with motivational approaches and CBT. Those who seek to integrate these skills into their daily practice require training, practice and regular feedback.

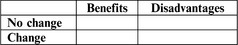

When the patient is ambivalent about the importance of change, it is useful to ask him to complete a grid, comparing the benefits and losses of change against those of no change (see Figure 2.4). Another strategy is to explore what would need to happen or alter to increase the importance of change for the patient. The patient should be able to express concerns about his current behaviour and the arguments for change, in order that his “decisional balance” is tipped towards action. This could also be seen as attempting to increase “motivational tension”.

The professional needs to be aware also of the effects of secondary gain, control and emotional expression within the patient’s illness behaviour. Most people know what is good for them and how to achieve it. Just as smoking-cessation interventions are ineffective when the “benefits” to the patient of remaining a smoker are ignored, so too can some features be overlooked within the psychological management of physical conditions. An example is the patient who, after a row with his or her partner, sabotages some aspect of the diabetic programme (ignores diet, omits medication) to force the partner to take the roles of rescuer and consoler. This sabotage may be how a patient expresses anger, but it has negative health consequences. In contrast, healthy people under stress, who push themselves too far and risk adverse health, are not “saboteurs”. The professional can uncover subconscious motives and challenge the patient, then help the patient take ‘ownership’ of his behaviour.