Chapter 46 Leukemic and lymphomatous infiltrates of the skin

Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation. CTCL-MF fast facts. Available at: http://www.clfoundation.org/publications/publications.htm. Accessed December 6, 2006.

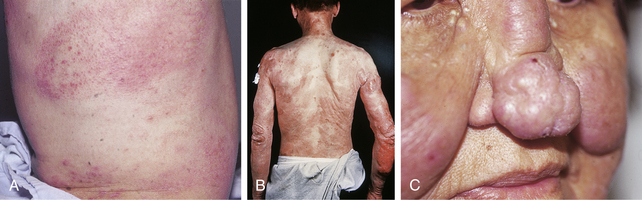

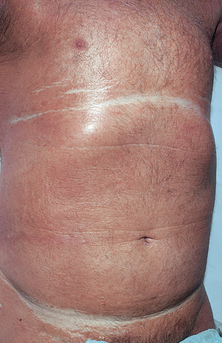

Large-plaque parapsoriasis presents as palm-sized or larger lesions located most frequently on the thighs, buttocks, hips, lower abdomen, and shoulder girdle areas (Fig. 46-2). The lesions may be pink, red-brown, or salmon-colored. They often have fine scale and show epidermal atrophy with cigarette-paper wrinkling. Some patients may have lesions with a netlike or reticular pattern with telangiectasia and fine scale. This clinical type of lesion is referred to as retiform parapsoriasis or poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare. Between 15% and 20% of patients with large-plaque parapsoriasis eventually develop mycosis fungoides.

Figure 46-2. Large-plaque parapsoriasis. The lesion was unresponsive to topical treatment.

(Courtesy of the Fitzsimons Army Medical teaching files.)

Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK: Parapsoriasis: a complex issue, Skinmed 6:280–286, 2007.

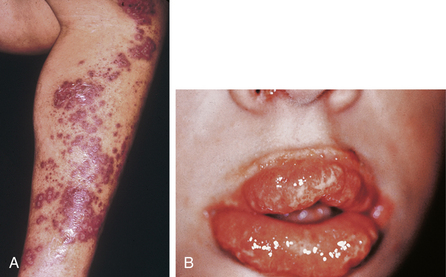

A rare variant of mycosis fungoides is granulomatous slack skin disease (Fig. 46-3). This disorder is characterized by the slow development of lax erythematous skin that eventually develops large pendulous folds of redundant integument. Histologic examination shows a dense atypical granulomatous infiltrate with destruction and phagocytosis of elastic tissue.

National Cancer Institute. Mycosis fungoides and the Sézary syndrome treatment. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/mycosisfungoides/healthprofessional/allpages. Accessed December 6, 2006.

Table 46-2. Cells Marked by CD Antigens

| CD2 | T cells (E rosette receptor) |

| CD3 | T-cell receptor |

| CD4 | Helper T cells |

| CD5 | Mature thymocytes, some B-cell subsets |

| CD7 | T cells, natural killer (NK) cells |

| CD8 | T cells, NK cells |

| CD10 | Pre-B cells, lymphoblastic leukemia cells |

| CD14 | Monocytes |

| CD15 | Reed-Sternberg cells, myeloid cells |

| CD19 | Pan-B cells |

| CD20 | Pan-B cells, dendritic cells |

| CD21 | Receptor for complement 2 and Epstein-Barr virus |

| CD23 | Activated B cells, monocytes, eosinophils, and platelets |

| CD25 | Activated T and B cells, monocytes (interleukin-2 receptor) |

| CD30 | Ki-1–related cells, Reed-Sternberg cells, T-cell NHL |

| CD34 | Lymphoid and myeloid precursor cells |

| CD43 | T cells, myeloid cells |

| CD45 | Leukocytes |

| CD45R | T cells, myeloid cells |

| CD56 | NK cells |

| CD74 | HLA-invariant chain |

| CD75 | Follicular center cells |

CD, Cluster of differentiation; HLA, histocompatibility locus antigen; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.