Lesional Morphology and Assessment

Albert C. Yan, Ho Jin Kim, Paul J. Honig

Introduction

Newborn infant skin can manifest with an extraordinary array of conditions. Neonatal cutaneous findings may indicate transitory, benign processes such as erythema toxicum neonatorum, or may represent important harbingers of internal disease or genetic alteration, as might be observed in patients with herpes simplex virus infection or incontinentia pigmenti. Dermatologic manifestations are readily visible to the clinician, and it is often more efficient to first assess lesional morphology and then focus history-taking on the basis of the observed clinical findings. The timely identification and accurate diagnosis of skin findings in the newborn infant therefore relies on combining a comprehensive history with a meticulous physical examination, as well as on a proper understanding of physiologic differences between neonatal, pediatric, and adult skin that will influence both the diagnosis and the management of skin conditions appropriate to the neonate. This chapter reviews the principles of morphologic assessment in the term and preterm infant.

Reaction patterns

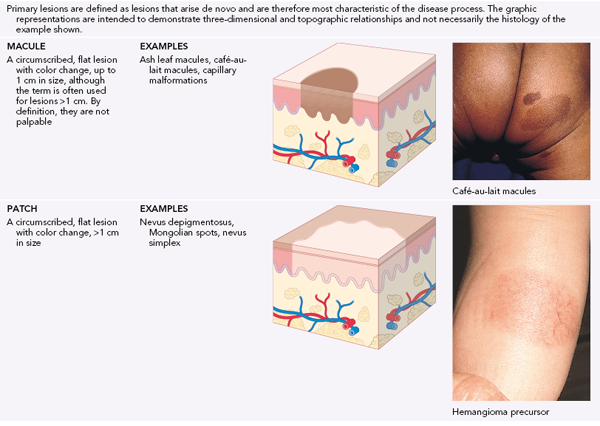

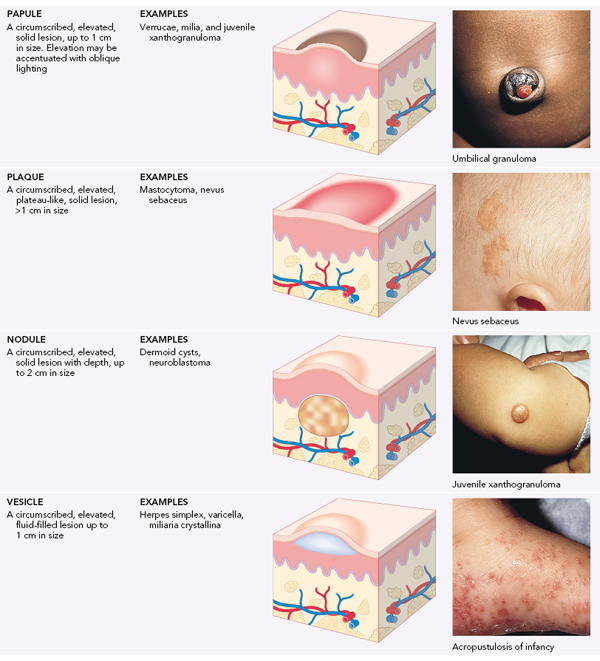

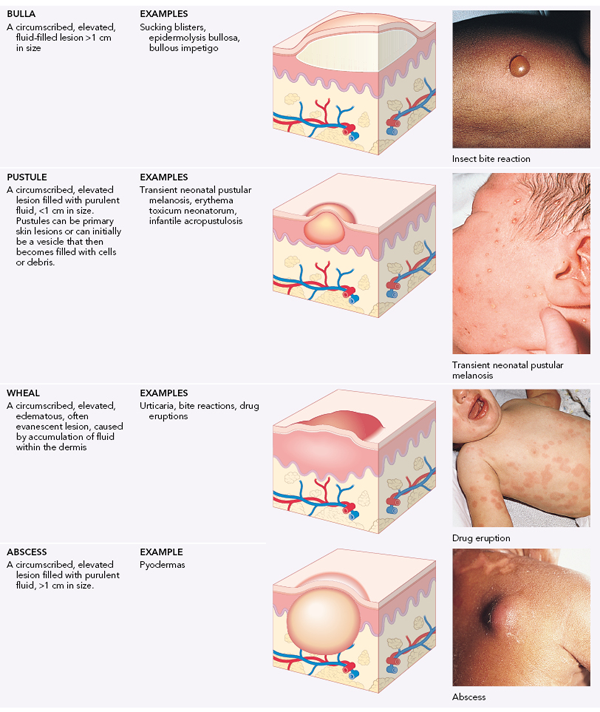

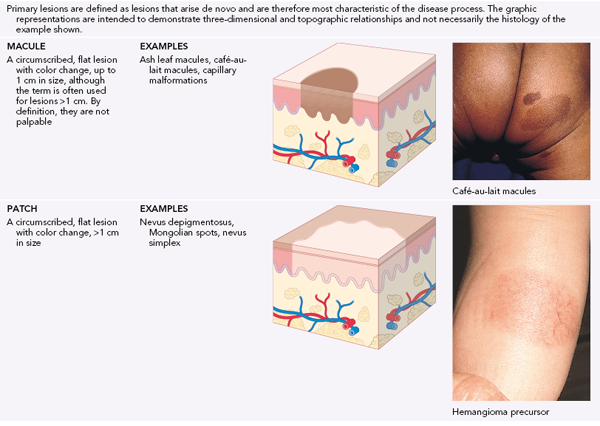

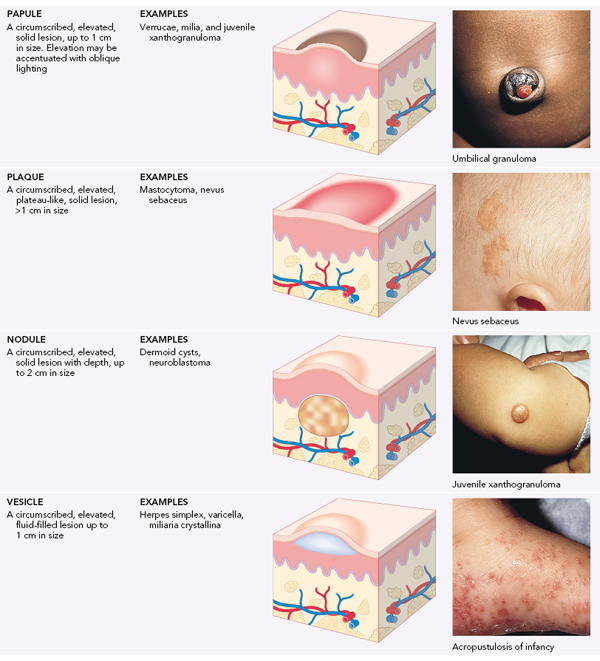

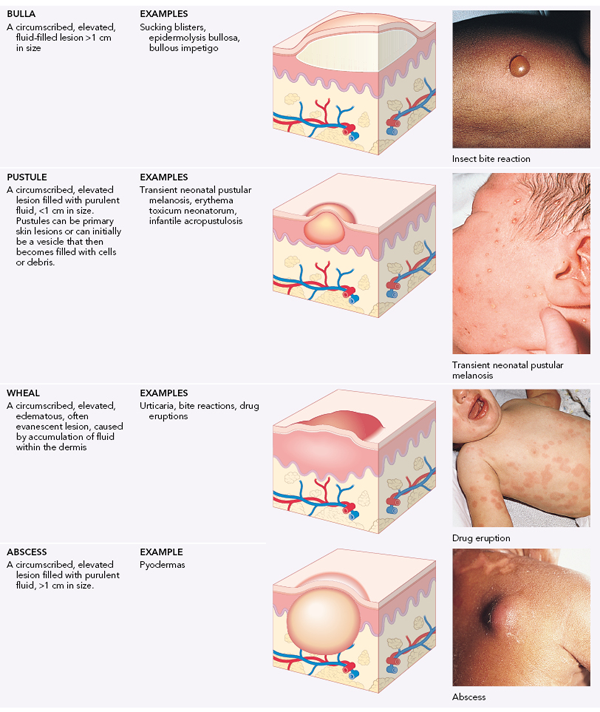

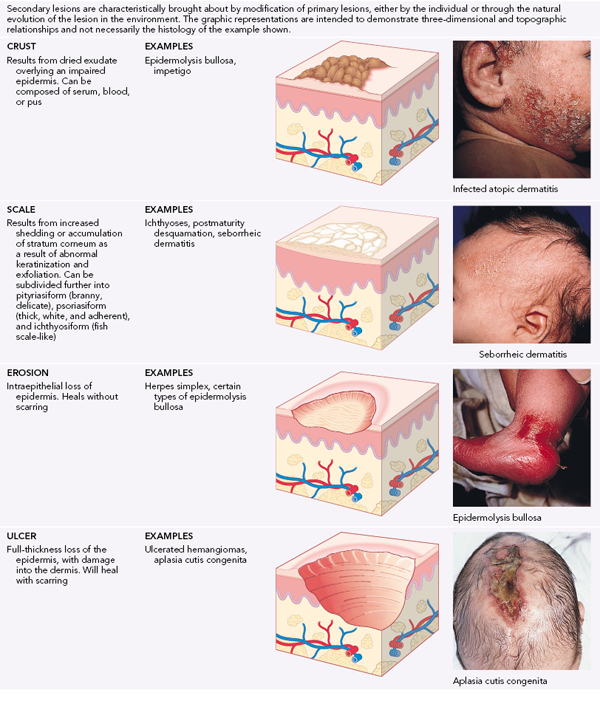

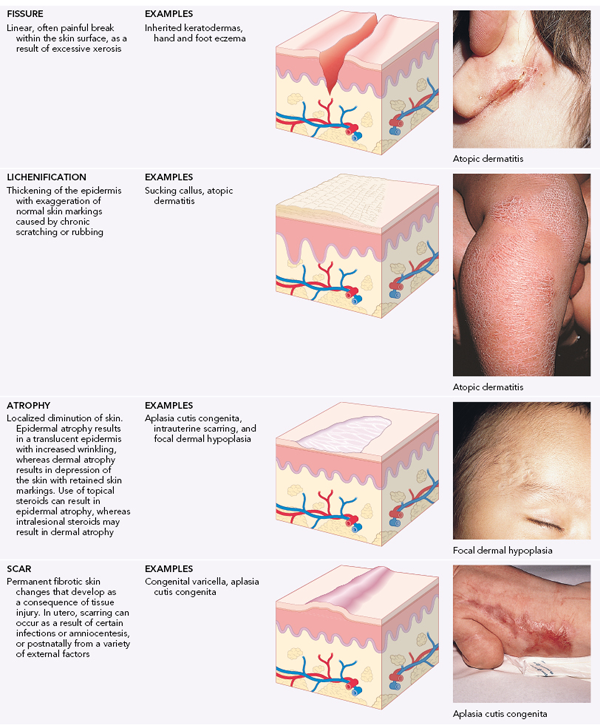

An understanding of the specialized reaction patterns is outlined in Tables 3.1–3.3 and Box 3.1 and, in conjunction with a comprehensive history and assessment of cutaneous morphology, will aid the clinician in making the proper dermatologic diagnosis.

TABLE 3.1

Primary lesions

Drawings reproduced with permission from Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders; 2012.

TABLE 3.2

Secondary lesions

Drawings reproduced with permission from Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders; 2012.

TABLE 3.3

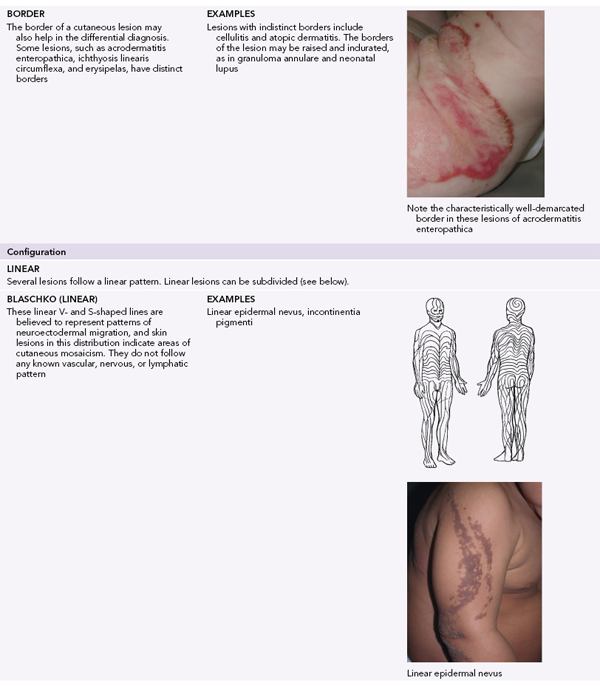

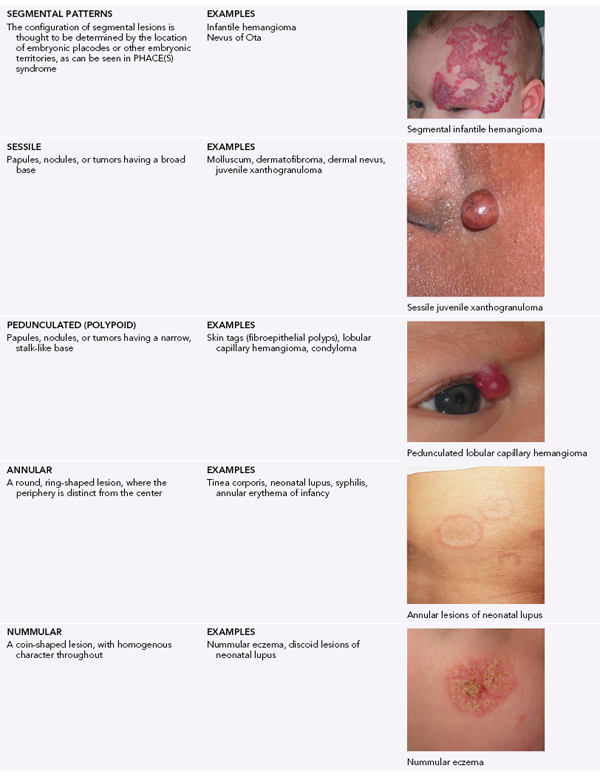

Borders, configuration, and distribution of lesions

The comprehensive history is a vital part of any neonatal skin evaluation. In the newborn setting, this includes not only prenatal and perinatal histories but also maternal, paternal, and family medical histories (Tables 3.1–3.2, Box 3.2). Prenatal history should focus on questions about possible antenatal exposures to medications, drugs, or infections. Questions should examine the use of prescription and non-prescription medications, as well as controlled and uncontrolled substances such as tobacco, alcohol, cocaine and other illicit drugs. Certain drugs, for example phenytoin, valproic acid, coumadin, diethylstilbestrol, systemic retinoids, tetracycline derivatives, and penicillamine, are known teratogens. As substance abuse among mothers has become more prevalent, our knowledge of their effects on the fetus is expanding. Specific cutaneous features may be observed with specific substances, as noted in fetal alcohol syndrome, where patients may manifest with short palpebral fissures, a broad flat nasal bridge, and a long upper lip with an absent or ill-defined philtrum.1 Other cutaneous findings of substance abuse are less specific and defined, but have been linked with premature birth and fetal growth retardation and its inherent cutaneous susceptibilities.2 Additional factors important in the prenatal history include maternal infections, especially within the first trimester when organogenesis occurs. The TORCH constellation of infections (toxoplasmosis, syphilis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes), human papilloma virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may have significant systemic and cutaneous effects on the infant, as addressed specifically in later chapters. Maternal history should include age, medical history, and outcomes of prior pregnancies. Certain genetic disorders have been linked to advanced maternal age during pregnancy, particularly chromosomal abnormalities, the most frequent being Down syndrome.3 Maternal disease may have a significant impact on the developing fetus. Systemic lupus erythematosus and related collagen vascular disorders highlight neonatal diseases that occur as a result of transplacental transmission of pathogenic antibodies – in this case anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB, or U1RNP antibody may result in an infant with neonatal lupus erythematosus.4 Other autoimmune disorders (such as bullous disorders), as well as chronic medical conditions requiring systemic medications, are also important in assessing the newborn. Medical conditions acquired during pregnancy, such as gestational diabetes, will also affect fetal development. Previous pregnancies that resulted in spontaneous abortions may suggest X-linked dominant conditions or autosomal recessive conditions that are fatal in utero. Failure to initiate or poor progression of labor may be the first clue to X-linked ichthyosis in the infant.5 Polyhydramnios has been associated with trisomies, and junctional epidermolysis bullosa with associated pyloric atresia.6,7 Paternal history, although less significant, may be useful. Increased paternal age has been linked to chromosomal abnormalities, in particular Down syndrome, Apert syndrome, achondroplasia, and neurofibromatosis.8–12 Finally, a detailed family history may help identify possible congenital anomalies or genetic disorders. The pattern of affected family members may indicate a specific mode of inheritance. A history of consanguinity should be sought if recessive genetic disorders are suspected. The history of labor and delivery should include approximate gestational dates. Premature, term, and postdate infants present with different cutaneous examinations, and are differentially susceptible to cutaneous disease. For instance, premature infants have a higher incidence of hemangiomas; term infants are more likely to develop erythema toxicum neonatorum; and postdate infants undergo significant desquamation shortly after birth. Identification of congenital cutaneous candidiasis in a preterm infant at high risk for systemic infection will warrant a different approach from term infants, for whom the disease poses significantly less of a risk. An excessively prolonged labor may indicate X-linked ichthyosis. Premature rupture of membranes, prolonged labor, and evidence of fetal distress due to hypoxia or meconium aspiration, may predispose an infant to cutaneous infection and subsequent sepsis. Low-birthweight infants must be watched with particular vigilance for signs of septicemia. Other risk factors for sepsis include male gender and prematurity, the risk being inversely proportional to gestational age. Apnea, bradycardia, irritability, feeding intolerance, temperature instability, abdominal distension, increased respiratory effort, hypotonia, and glucose instability can be subtle early signs of sepsis. Cutaneous findings of infection may include a full or bulging fontanelle, generalized erythema, petechiae, purpura, and vasomotor instability, with poor peripheral circulation (i.e. mottling and cyanosis of the acral areas).13 The umbilical area, as well as central venous or arterial catheterization sites, should be evaluated closely as potential portals of entry. Prolonged labor, abnormal presentation, and artificial extraction measures may account for petechiae, ecchymoses, and hematomas which may herald the onset of hyperbilirubinemia. In certain disorders, such as congenital malignancies (e.g., melanoma) or congenital infections (e.g., chorioamnionitis), examination of the placenta may be helpful. Although historical evidence is important, the cornerstone of dermatology remains a careful, detailed cutaneous examination. This requires both visual and tactile assessment of the skin. Special precautions must be followed in the newborn nursery, especially in the intensive care unit setting. Careful handwashing or the use of newer topical broad-spectrum antimicrobial hand preparations, with removal of jewelry, must be performed to reduce the risk of nosocomial infections.14,15 Some infants may require incubators to maintain their temperature and fluid balance. During examination, prolonged exposure outside of the isolette can result in hypothermia. Open radiant warmers are helpful, but prolonged exposure should be avoided because open warmers will increase transepidermal water loss. When examining an infant, good lighting and adequate exposure are essential. Although natural lighting is best, this is rarely available. Fluorescent lights and bilirubin lights may mask some of the subtle contours and colors of individual lesions. Where practical, the infant should routinely have all clothing removed, including diapers, so that the entire skin surface can be examined. A great deal of similarity may occur between pathologic processes. Although some diagnoses are obvious, there is only a finite number of ways that skin can express disease. An organized approach to evaluating and describing lesions is of paramount importance. Examination of the skin surface should proceed systematically from inspection to palpation, separating the body into segments to ensure complete evaluation. Inspection of the lesions should characterize the primary and secondary lesions; the colors involved; the borders; the configuration; and the distribution of relevant cutaneous findings. Relevant primary and secondary lesions should first be identified (Tables 3.1 and 3.2). An understanding of the significance of these primary and secondary lesions will not only help generate an appropriate differential diagnosis but also allow for concise communication of pertinent data to colleagues. We have attempted to use the most commonly used definitions for primary and secondary lesions. Unfortunately, a review of the core dermatologic textbooks and literature reveals a great deal of inconsistency among these definitions.16–20 Subsequently, the color, borders, configuration, and distribution of lesions are assessed (Table 3.3 and Box 3.1). When evaluating color, one should take into account the variations in different ethnic groups because background color will alter the overall color of lesions. The border should be examined for distinct or indistinct margins. Next, configuration should be assessed. Are the lesions linear, annular, nummular, targetoid, grouped, or retiform? Finally, the last step is the evaluation of distribution. Is the lesion single or multiple, localized or generalized, symmetric or asymmetric, extensor or flexural, acral, or inverse? This is then followed by palpation of the lesion, with particular attention to the border. Lesions may be soft, firm, fluctuant, indurated, or tender. Mucous membranes, teeth, hair, and nails should be included in a full cutaneous examination. Teeth, hair, and nails are ectodermal structures like the skin, and can be intimately linked to cutaneous pathologic processes. Teeth are normally absent at birth, but natal teeth, which represent prematurely erupted primary incisors, can be seen. Delayed onset of eruption, absent or abnormal teeth, or enamel dysplasia can be seen in the ichthyoses, ectodermal dysplasias, and other genodermatoses such as incontinentia pigmenti and tuberous sclerosis. Sparse to abundant hairs can be seen as a variation of normal. Synchronous loss of hair followed by regrowth is a normal finding until the development of an adult hair distribution, usually during the first year of life. Subtle changes in hair texture with a matted, lusterless, brittle, or unruly appearance should prompt closer evaluation by light microscopy for hair shaft abnormalities, which can be elucidated with scanning electron microscopy. Diffuse hypotrichosis can be seen in hidrotic and anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, ichthyoses, and incontinentia pigmenti. Diffuse hypertrichosis can be seen in mucopolysaccharidosis, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, and hypertrichosis lanuginosa. Nail abnormalities, in particular aplasia, hypoplasia, and dysplasia, have been associated with chromosomal disorders, ectodermal dysplasias, and epidermolysis bullosa. Absent nails or triangular lunulae have been associated with nail–patella syndrome. Finally, to complete the cutaneous examination, the lymph nodes, liver, and spleen should be palpated, particularly when infectious or neoplastic diagnoses are suspected. Cutaneous reaction patterns in newborns can differ significantly from those seen in children and adults, because of the immaturity of the skin and its components. Although the precise mechanisms have not been fully elucidated, there are numerous clinical examples of such differences. Although all the known dermoepidermal junction antigens are made by the middle of the second trimester, the lack of a developed rete ridge pattern and well-developed collagen fibrils within the papillary dermis may explain the greater propensity for vesicle formation in the newborn.21 The epidermis, particularly in immature infants, has a relatively thin stratum corneum, which results in increased transepidermal water loss, making infants more susceptible to xerosis. Furthermore, the immature epidermis is quite fragile and prone to trauma at sites of maceration and friction, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Even mild adhesive can strip the epidermis, causing significant damage.22 The loss of this barrier function increases susceptibility to cutaneous infection with both bacteria and Candida species. The composition of neonatal subcutaneous fat, with its greater proportion of saturated fatty acids, makes it more prone to hypoxic trauma, leading to subcutaneous fat necrosis.23 The immaturity of the cutaneous vasculature, with its exaggerated vasomotor tone in response to hypothermia, contributes to the prevalence of cutis marmorata in infancy.24 Access the full reference list at ExpertConsult.com Albert C. Yan, Ho Jin Kim, Paul J. Honig Newborn infant skin can manifest with an extraordinary array of conditions. Neonatal cutaneous findings may indicate transitory, benign processes such as erythema toxicum neonatorum, or may represent important harbingers of internal disease or genetic alteration, as might be observed in patients with herpes simplex virus infection or incontinentia pigmenti. Dermatologic manifestations are readily visible to the clinician, and it is often more efficient to first assess lesional morphology and then focus history-taking on the basis of the observed clinical findings. The timely identification and accurate diagnosis of skin findings in the newborn infant therefore relies on combining a comprehensive history with a meticulous physical examination, as well as on a proper understanding of physiologic differences between neonatal, pediatric, and adult skin that will influence both the diagnosis and the management of skin conditions appropriate to the neonate. This chapter reviews the principles of morphologic assessment in the term and preterm infant. An understanding of the specialized reaction patterns is outlined in Tables 3.1–3.3 and Box 3.1 and, in conjunction with a comprehensive history and assessment of cutaneous morphology, will aid the clinician in making the proper dermatologic diagnosis. TABLE 3.1 Primary lesions Drawings reproduced with permission from Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders; 2012.A comprehensive history and its impact

Prenatal history

Maternal history

Cutaneous examination and evaluation

Considerations unique to the neonatal period

![]()

Lesional Morphology and Assessment

Introduction

Reaction patterns