Leg and Forearm Fasciotomy

Leg Fasciotomy

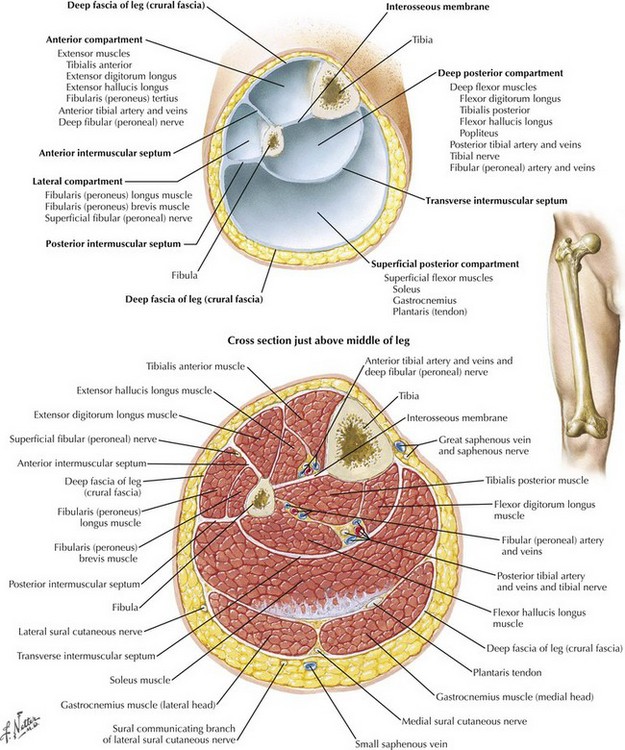

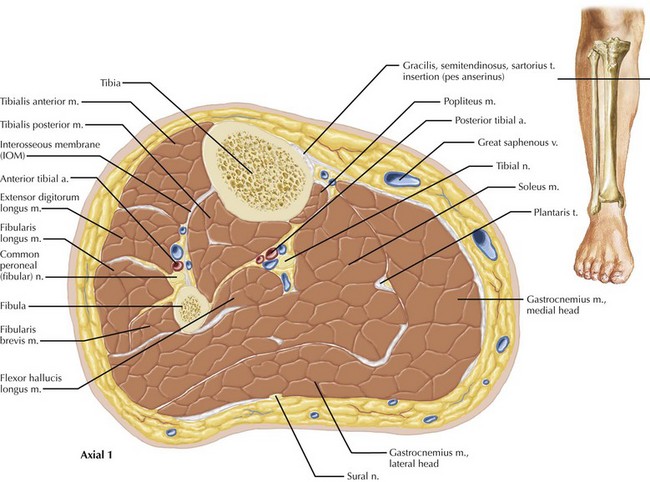

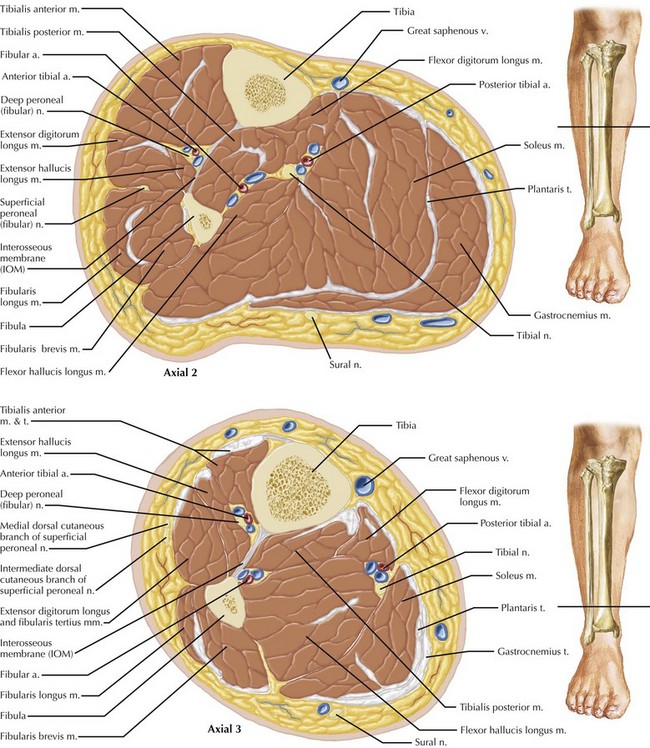

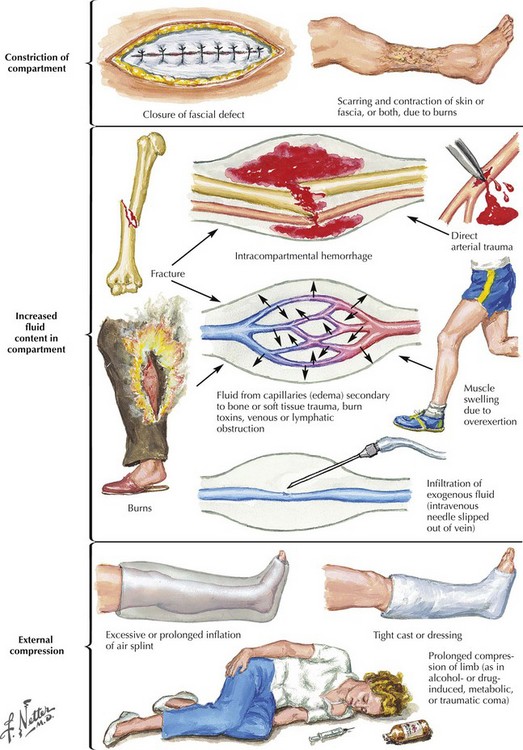

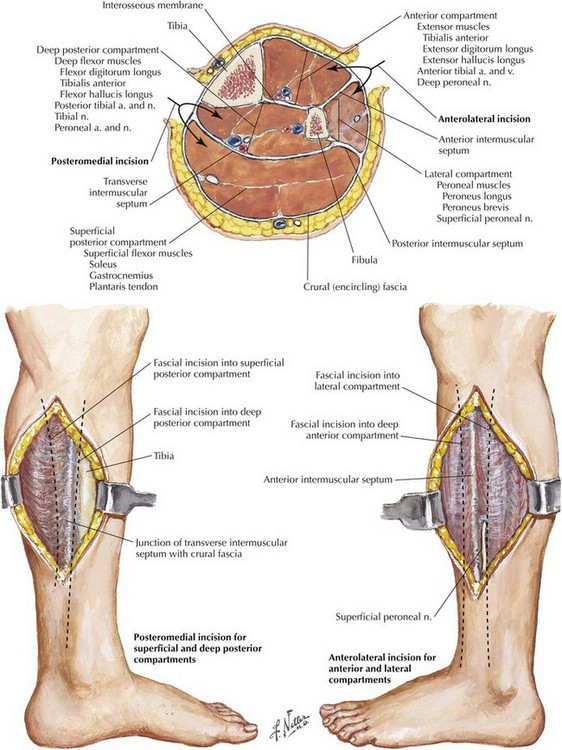

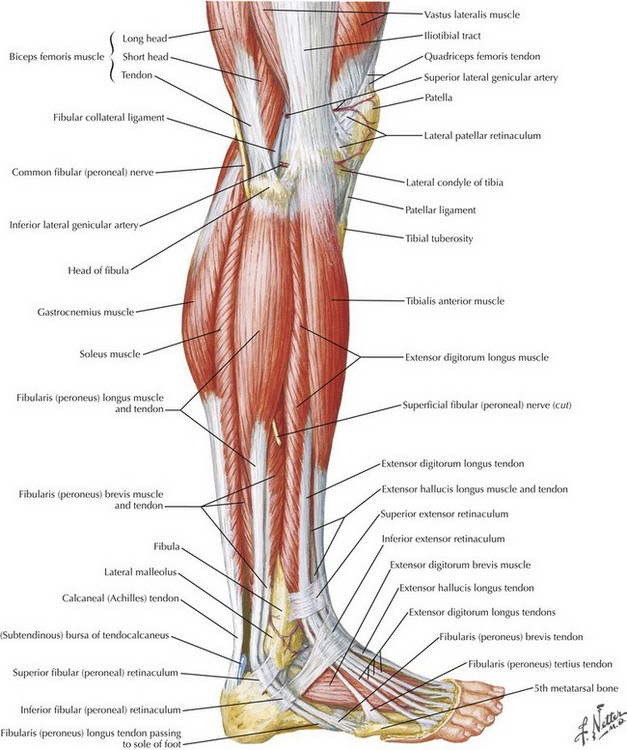

The lower leg is divided into four compartments: anterior, lateral, superficial posterior, and deep posterior (Fig. 42-1). The anterior compartment is especially prone to ischemic injury because of its relative paucity of collateral arterial supply. Compared with the other compartments, especially the posterior compartments, the anterior compartment is also more firmly constrained. The spatial relationships among the nerve, vascular, muscular, and bony structures change from proximal to distal in the leg, an especially relevant consideration in performing complete lysis of the posterior compartments (Figs. 42-2 and 42-3).

Etiology of Compartment Syndrome

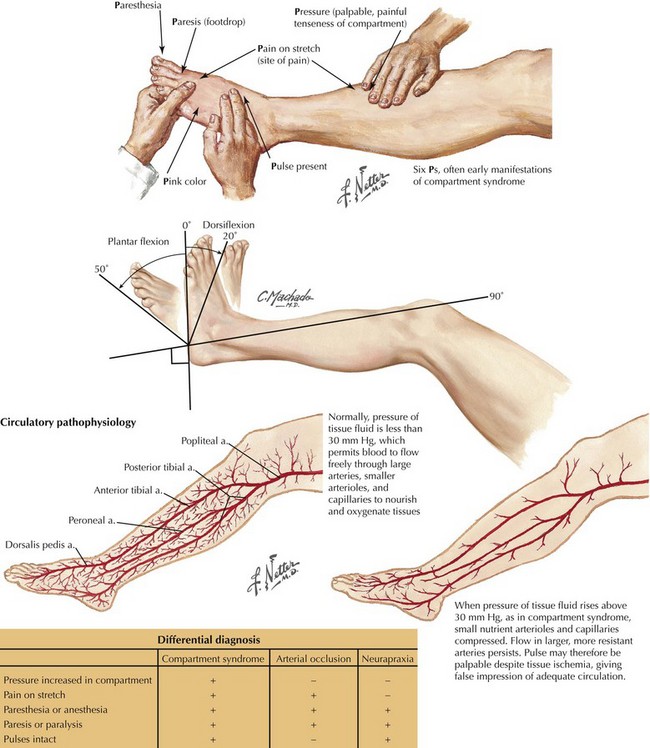

Compartment syndrome occurs when the compartmental pressure rises sufficiently to prevent adequate tissue perfusion. This condition can result from increased volume in the compartment caused by bleeding, infiltration of exogenous fluid, or reperfusion edema (Fig. 42-4). Increased compartment pressures can also result from external constraint on the compartment, such as with casts, braces, or bandages. A compartment pressure greater than 30 mm Hg is accepted as sufficiently elevated to cause compartment syndrome. This pressure is usually sufficient to restrict venous outflow from the compartment, thereby leading to further increases in compartment pressure.

Clinical Diagnosis and Decision Making

In the appropriate clinical setting, compartment syndrome should always be considered. Pain is the most prevalent symptom, but the patient may report diminished motor strength and altered or reduced sensation (Fig. 42-5). Pain with passive movement and palpation is extremely common, although the absence of pain in the extremity with compromised neurologic function can be misleading.

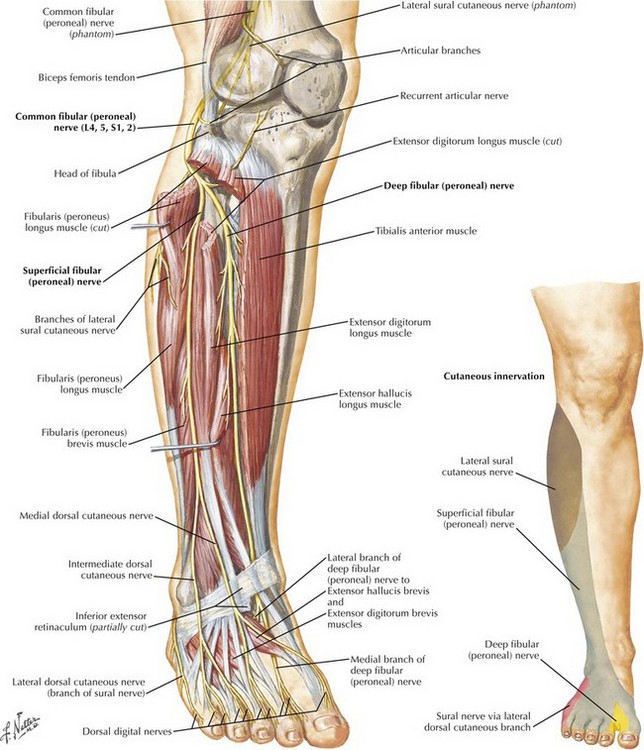

Light touch sensation is often diminished before the development of motor weakness and can best be tested in the web space between the first and second toes. Touch sensation reflects the function of the deep peroneal nerve (Fig. 42-6).

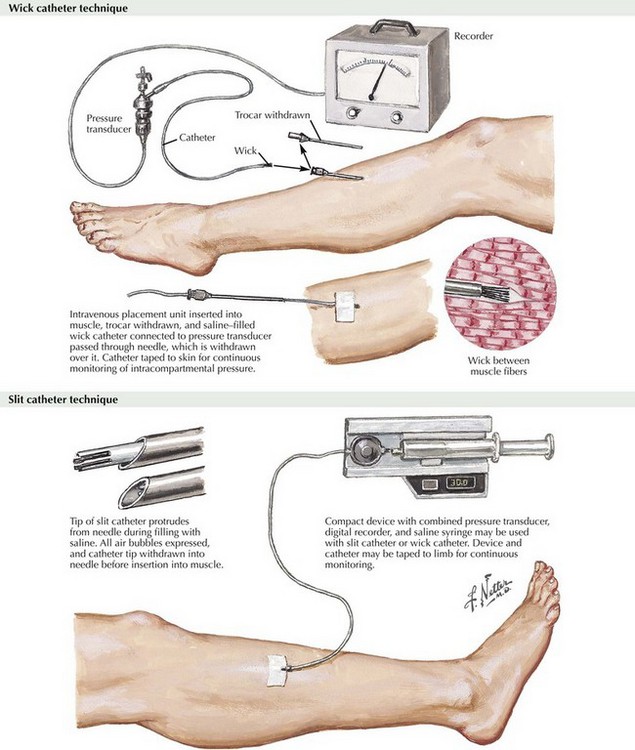

When findings are equivocal, compartment pressure can be measured by introducing a needle or intravenous catheter into the compartment(s) and directly measuring the pressure (Fig. 42-7). The decision to perform fasciotomy is made on the basis of the index of suspicion, clinical findings, and presence of increased compartment pressure. In the appropriate clinical setting with positive physical findings, compartment pressure measurements are not required to justify fasciotomy.

Surgical Anatomy and Technique

Fasciotomy in the leg can be achieved with a single lateral incision. More frequently, both medial and lateral incisions are used (Fig. 42-8). The medial incision is used to decompress the posterior compartments, and the lateral incision addresses the anterior and lateral compartments. The medial incision is made approximately 1 to 2 cm posterior to the medial margin of the tibia.

The saphenous nerve is parallel and immediately adjacent to the long saphenous vein in the lower leg, and inadvertent injury to this sensory nerve should also be avoided. The proximal third of the soleus muscle is attached to the tibia and fibula. In addition to entering the posterior deep compartment in the middle and distal leg, the soleus must be detached from the tibia for adequate lysis of the proximal portion of the posterior deep compartment (Fig. 42-9).

Forearm Fascotomy

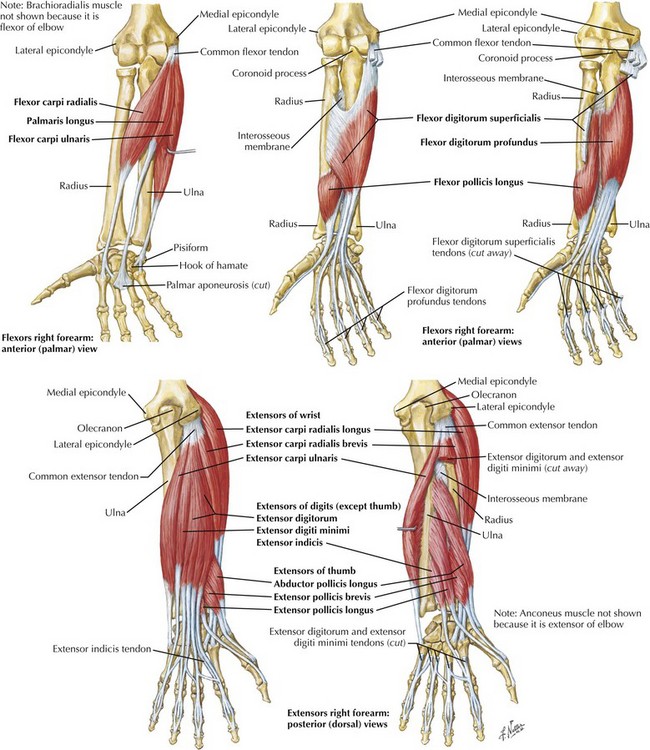

The forearm compartments consist of a single volar compartment and two dorsal compartments. The volar compartment has distinct septae within its muscle groups. There are typically two to three subcompartments arranged in a volar-to-dorsal direction. The most superficial of these contains the flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, flexor carpi ulnaris, and superficial portion of the pronator teres (Fig. 42-10). The next division contains the flexor digitorum superficialis, and the flexor digitorum profundus and flexor pollicis longus make up the final section. The main dorsal compartments are divided into the extrinsic finger extensors, thumb extensors with the index proprius, and the wrist extensors with the brachioradialis muscle. These anatomic divisions are important to consider during fasciotomy of the forearm.

Clinical Diagnosis and Decision Making

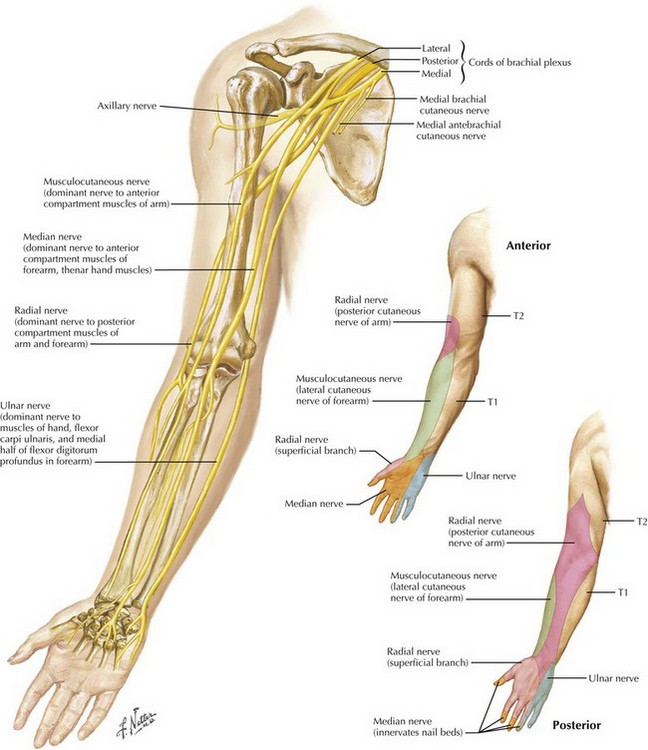

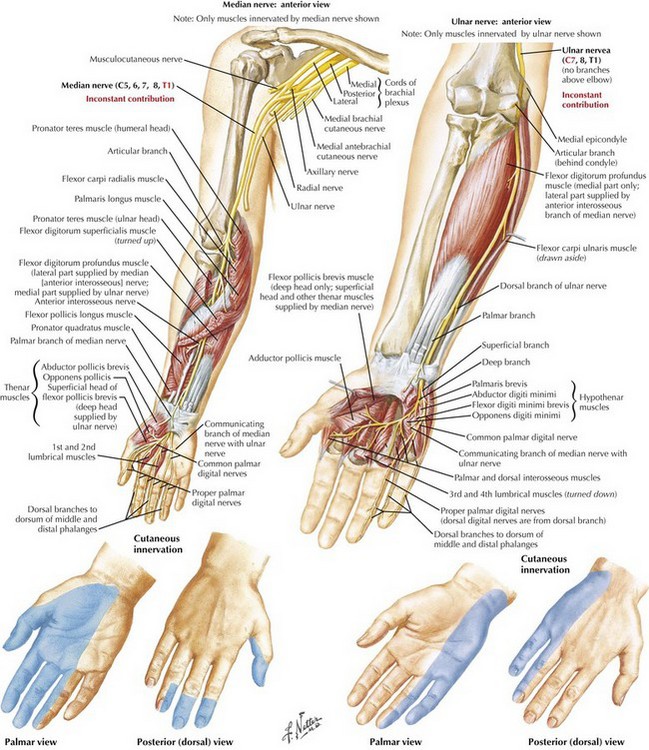

The classic findings of forearm compartment syndrome are disproportionate pain in view of the physical exam, pain with passive stretch of the finger extensors, restricted finger and wrist motion, and paresthesias in the hand along the distribution of the median, the ulnar, and less often the radial nerve (Fig. 42-11). There may be pallor in the terminal digits with prolonged capillary refill and decreased skin temperature. As this condition progresses, complete anesthesia occurs, and the radial and ulnar pulses can be diminished in severe cases.

Surgical Anatomy and Technique

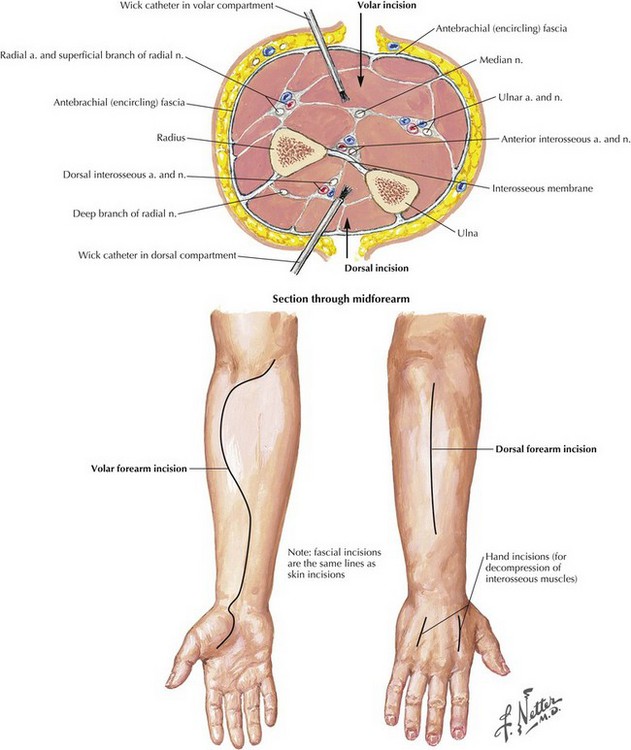

The fascia overlying the respective compartments should be completely incised. The septae between the muscle groups is also incised to ensure full decompression (Figs. 42-12 and 42-13). Often the deepest or most dorsal volar subcompartment is involved in early cases. This compartment is not well visualized without a deeper dissection. In more severe cases this compartment often has the most muscle destruction. The relationship of the median and ulnar nerves within the compartments is such that the ulnar nerve lies adjacent to the flexor digitorum profundus muscle, and the median nerve is generally between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus muscles in the midforearm. The anatomy can be quite distorted as a result of the excessive swelling. The necessity for further surgical intervention is determined by the extent of muscle necrosis.

Sheridan, GW, Matsen, FA. Fasciotomy in the treatment of the acute compartment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:112.

Velmahos, GC, Theodorou, D, Demetriades, D, et al. Complications and nonclosure rates of fasciotomy for trauma and related risk factors. World J Surg. 1997;21:247.

Williams, AB, Luchette, FA, Papaconstantinou, HT, et al. The effect of early versus late fasciotomy in the management of extremity trauma. Surgery. 1997;122:861.

http://www.operationgivingback.facs.org/stuff/contentmgr/files/a384bb3c7b77e154ad25c6136d7be344/miscdocs/lab_manual_extremity_chapter_4__2_.pdf.