Left Ventricular Systolic Function

Eric W. Nelson

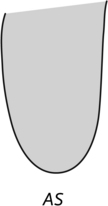

For some reason there is a lot of focus on the left ventricle and its evaluation on TEE, both in the operating room and on the boards. This most likely has to do with the fact that it’s pumping blood to the entire body, thus keeping you alive. The easiest way to start your evaluation of the left ventricle is to know what a normal left ventricle looks like.

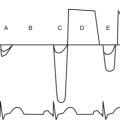

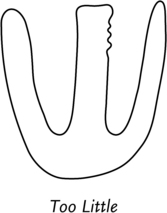

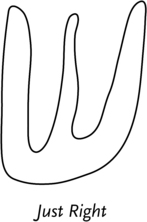

EF can be calculated by measuring the fractional area of change (FAC) of the left ventricle. A true long- or short-axis cross section is required being careful not to foreshorten. Foreshortening is a term commonly used by echocardiographers to describe the heart when it is compressed because of the viewpoint taken. With modern TEE machines all you have to do is outline the end-diastolic area and the end-systolic area and the machine will crunch the numbers.

FAC = (end-diastolic area – end-systolic area)/end-diastolic area

Abnormal LV Systolic Function

Ischemia, just can’t say it enough.

Ischemia, just can’t say it enough.

Ventricle—infiltrative diseases that cause restrictive physiology such as amyloidosis cause global impairment.

Ventricle—infiltrative diseases that cause restrictive physiology such as amyloidosis cause global impairment.

Pericardial space—tamponade either from an effusion or blood. TEE is great at not only making this diagnosis, but also locating where the effusion is around the heart and whether it is loculated.

Pericardial space—tamponade either from an effusion or blood. TEE is great at not only making this diagnosis, but also locating where the effusion is around the heart and whether it is loculated.

Pleural space—tension pneumothorax causes decreased venous return thus decreasing preload and ventricular function.

Pleural space—tension pneumothorax causes decreased venous return thus decreasing preload and ventricular function.

Metabolic—hypoxemia, hypoglycemia, anemia, hyperkalemia, and a vast array of other metabolic abnormalities.

Metabolic—hypoxemia, hypoglycemia, anemia, hyperkalemia, and a vast array of other metabolic abnormalities.

Cardiomyopathies

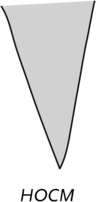

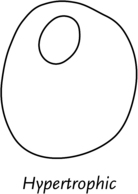

Hypertrophic

HOCM is an inherited cardiomyopathy. It is autosomal dominant with limited penetrance, unless of course you are the patient then it is a very penetrating diagnosis!

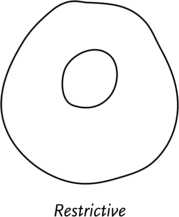

Restrictive

glycogen from patients with glycogen storage disease

glycogen from patients with glycogen storage disease

eosinophils from eosinophilic myocarditis (also known as Loffler’s)

eosinophils from eosinophilic myocarditis (also known as Loffler’s)

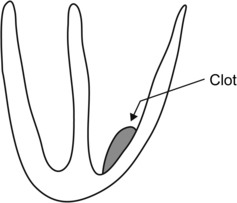

Patients with restrictive heart disease are also prone to thrombus formation even without a wall motion abnormality. Thrombi are typically found in the apex. Remember, the apex of the heart is best visualized in the mid-esophageal 2-chamber view and the mid-esophageal 4-chamber view. Thrombi may also form under the posterior mitral valve leaflet, which may lead to a bit of mitral regurgitation.

Questions

1. Which wall is spared in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy?

2. Which of the following may cause cardiomyopathy?

3. Where is the most likely place to find thrombus in the LV?

4. Treatment for HOCM includes all of the following except:

5. What causes hemodynamic compromise in patients with HOCM?

6. Which of the following causes restrictive cardiomyopathy?

7. Which of the following patients are prone to LV thrombus formation:

8. A problem in which of the following spaces may affect LV systolic function?

9. True or false: It is possible to evaluate the ejection fraction of the heart by one view on TEE