Left Colectomy

Anatomy for Preoperative Imaging

For colonic carcinoma, computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis provides preoperative staging of the disease. CT includes identification of distant metastases, gross local lymph node involvement, and local invasion of the primary tumor (Fig. 22-1, A). Full colonoscopic evaluation determines the presence of synchronous lesions. For benign disease, CT and colonoscopy may help to identify pathologic features, such as the extent of Crohn disease or ischemia, that may affect approach and extent of dissection.

Surface Anatomy, Incision, and Port Placement

A number of different port configurations have been described; the authors’ preferred approach is shown in Figure 22-1, B. Open left hemicolectomy may be performed through either a midline or a left transverse incision.

Vascular Anatomy

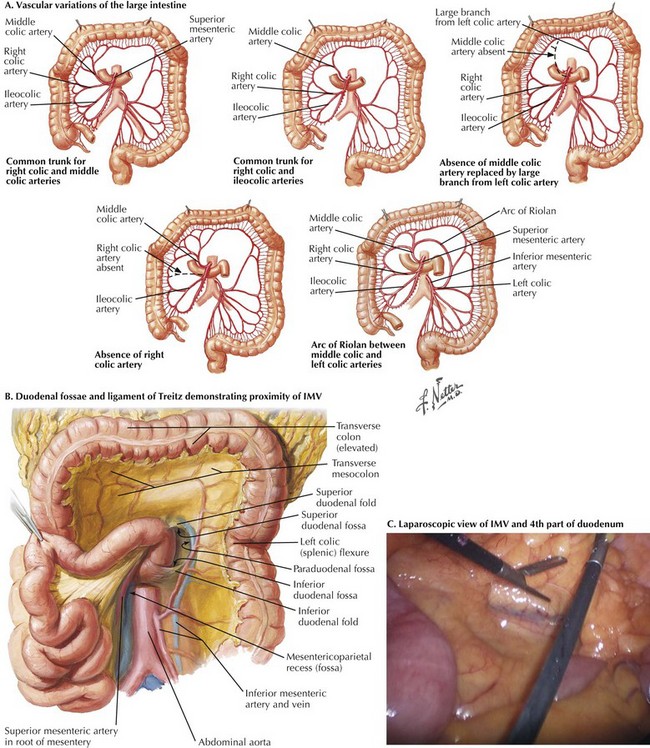

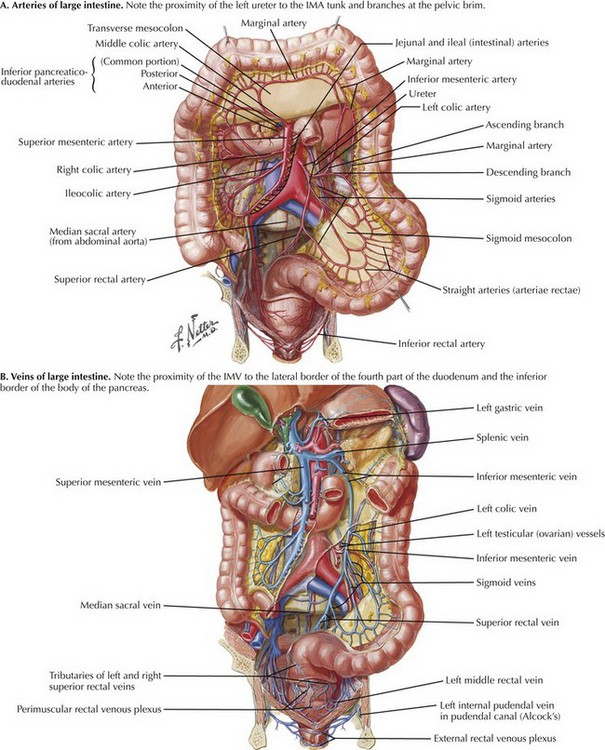

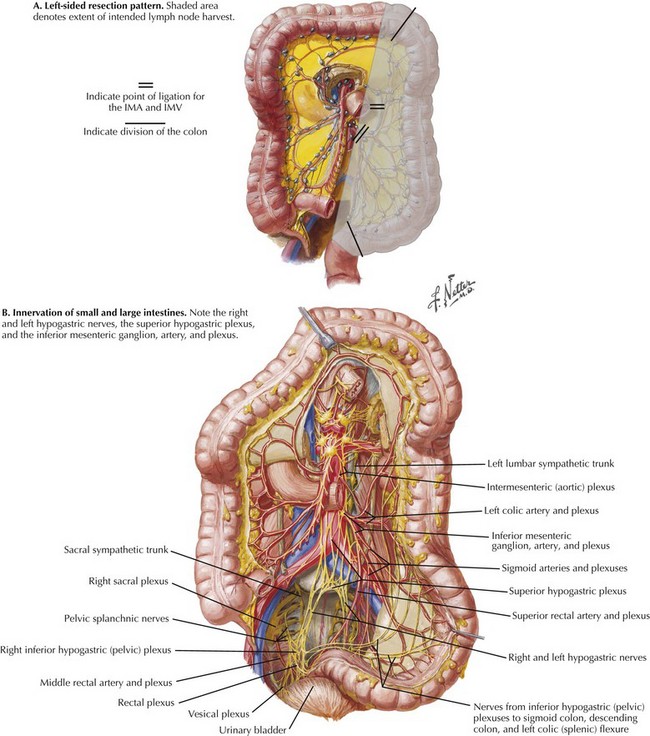

The anatomy of the vascular supply to the colon is demonstrated in Figure 22-2. Knowledge of these vessels, the autonomic nerves, and the lymphatic drainage, as well as its relationship to the spleen, pancreas, kidney, and ureter, is required for successful completion of the left hemicolectomy (Figs 22-3 and 22-4, A).

FIGURE 22–2 Vascular supply to colon.

IMA, Inferior mesenteric artery; IMV, inferior mesenteric vein.

FIGURE 22–3 Left resection pattern; autonomic nerves and lymphatic drainage to colon.

IMA, Inferior mesenteric artery; IMV, inferior mesenteric vein.

The arterial blood supply to the left colon is derived from the IMA, which is the most distal of the three midline branches of the abdominal aorta. The ascending left colic or left colic artery is the first branch of the IMA. This supplies the descending colon and the splenic flexure, via the marginal artery of Drummond. The marginal artery joins the middle colic branch of the superior mesenteric artery in the midtransverse colon (see Fig. 22-2, A). The arterial supply to the splenic flexure is subject to a great degree of variability (Fig. 22-4, A). The marginal artery may be augmented by a second arcade, located more proximally in the mesocolon, known as the arc of Riolan. Also, both the marginal artery of Drummond and the arc of Riolan may be absent. Therefore, if the IMA and its branches have been ligated, it is essential to assess the vascularity of the colon at the proximal resection margin intraoperatively to ensure an adequate blood supply to the anastomosis.

Venous drainage of the left colon and hindgut is through tributaries of the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) (see Fig. 22-2, B). The IMV lies in the base of the left mesocolon and passes posterior to the lower border of the pancreas, just lateral to the 4th portion of the duodenum. Under the pancreas, the IMV joins the splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein to form the portal vein. The IMV is significant in colorectal disease because it tethers the left colon, and high ligation is necessary for full left colon mobilization. Division of the IMV 1 inch (2.5 cm) below the inferior border of the pancreas provides several inches of extra mobility, often assisting the creation of a tension-free anastomosis (Fig. 22-4, B and C).

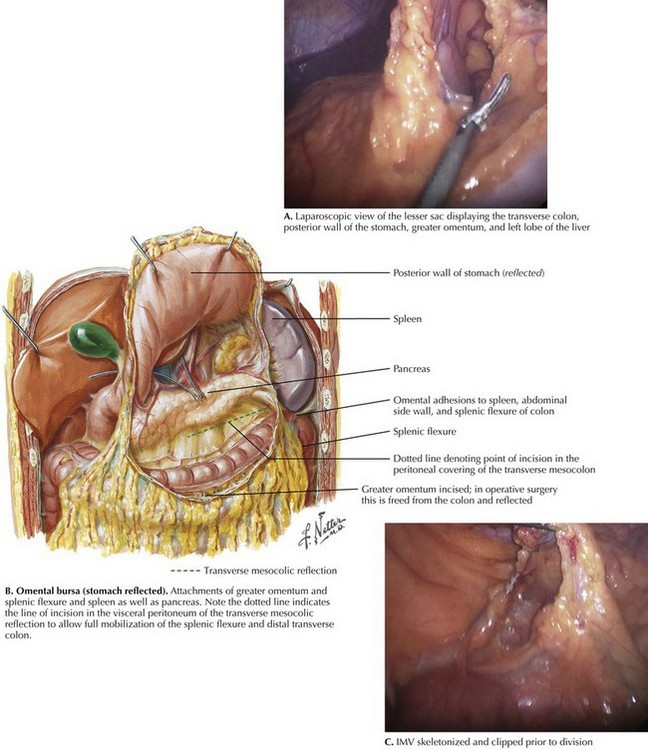

Splenic Flexure

Starting at the midtransverse colon, the greater omentum is elevated superiorly, demonstrating the avascular plane between omentum and transverse colon. At its left lateral extent, the omentum often exhibits adhesions to both the splenic flexure and the capsule of the spleen. Traction on the flexure may cause inadvertent trauma to the spleen. This complication may be mitigated by superior/cephalad retraction of the greater omentum in the midline and commencing dissection in the midtransverse colon. Opening this plane medially provides entry to the lesser sac, identified by visualization of the posterior wall of the stomach, and exposes the superior aspect of the transverse mesocolon (Fig. 22-5, A).

As with the lateral descending and sigmoid mobilization, there is a line of reflection between the parietal and visceral peritoneum. This line is less easy to see than the white line of Toldt but is present nevertheless (Fig. 22-5, B). The peritoneum must again be incised just above this line of reflection (closer to the colon). Mobilization too far from the retroperitoneum (too close to the colon) makes a defect through the mesentery of the colon. While mobilizing, attention must be paid to the jejunum, which is often only a layer of peritoneum away from the area of dissection. Superior mobilization is complete when the colon to the left of the midline is fully freed from its superior attachments.

Full mobilization of the splenic flexure requires division of the IMV. The inferior approach to the splenic flexure uses this as the starting point. With the transverse colon retracted superiorly and the small bowel retracted to the patient’s right, the 4th part of the duodenum and ligament of Treitz are visualized (see Figs. 22-4, B and C, and 22-5, C). This approach exposes the IMV inferior to the vessel passing posterior to the pancreas. Once this has been divided, with Toldt’s fascia identified, mobilization of the proximal descending colon continues from medial to lateral, through the mesocolon to the left lateral side wall. The retroperitoneum, gonadal vessels, and ureter are protected deep to the dissection, and the mesocolon and colon are preserved anteriorly.

Sigmoid and Descending Colon

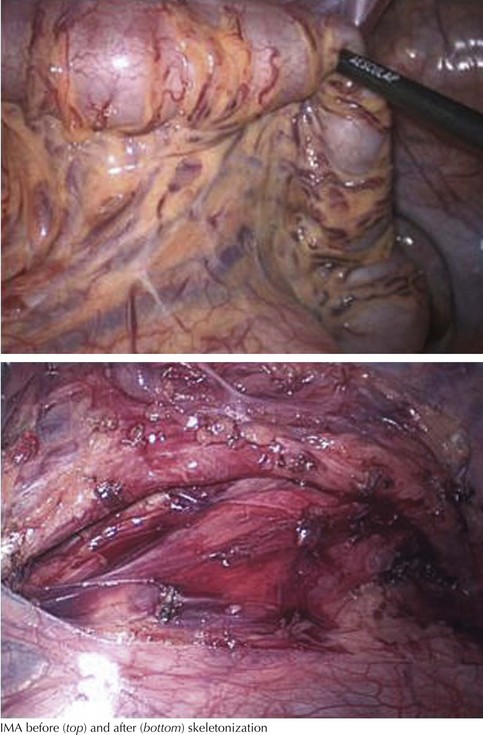

The peritoneum is scored proximal and distal to the inferior mesenteric artery. This approach allows the origin of the IMA to be encircled before division (Fig. 22-6), and it is the first step in a laparoscopic medial-to-lateral approach. Having confirmed the plane of dissection and preservation of the ureter in the retroperitoneum, the surgeon continues dissection laterally to the lateral peritoneal attachment.

Rather than aiming for flush ligation at its origin, a 1- to 2-cm length of the IMA should be preserved, to ensure that the superior hypogastric plexus of the autonomic nervous system is not inadvertently damaged where it encircles the IMA (Fig. 22-6). For tumors of the left colon, the IMA should be divided proximal to the takeoff of the left colic artery to ensure a full lymphadenectomy.

Upper Mesorectal Mobilization, Transection, and Anastomosis

Although by definition, no rectum is resected in a left hemicolectomy, it is often necessary to mobilize the proximal rectum to allow the passage of the circular stapling devices for a stapled anastomosis, or to ensure a good blood supply to the distal component of the anastomosis. This approach is covered in detail in Chapter 24.

Farquharson, M, Moran, B, Farquharson’s textbook of operative general surgery, 9th ed, 2005.

Kirk, RM, Winslet, MC. Essential general surgical operations, 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingston; 2007.

Sinnatamby, CS. Last’s anatomy: regional and applied, 12th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2011.