3 Leadership, teamwork and resuscitation aids

Pointers for effective team leading

1. A leader must firstly be identified – either a willing volunteer or a pre-appointed senior clinician could assume this role. If possible, pre-allocation of roles, especially the team leader role, can avoid delay and consternation when an actual resuscitation is encountered.

2. Confidence comes from practice and is vital for a resuscitation team leader. It comes from knowing the resuscitation guidelines (or other protocols) well enough to apply them automatically. Do as much clinical work as you can under an experienced team leader whom you respect. Confidence also comes from good quality, practical, integrated, scenario-based training (see Box 3.1).

3. Self-confidence is also derived from knowing where to access the information you need during the management of an emergency. It is important to know where to get the information, the relevant algorithms and resuscitation aids, as well as how they work. Do not be pressured into trying to recall information, dosages and causes. It will be far more accurate and consistent to refer to resuscitation aids (see Box 3.2).

4. The leader should delegate functions to each team member in accordance with their expertise, experience and abilities. This can either be done immediately as the team forms around the patient or at the beginning of the shift in an ED.

5. Management by objectives is an age-old leadership tool which can neatly be applied in the resuscitation setting. The objectives for the resuscitation or medical procedure (e.g. rapid sequence intubation), as well as how these will be achieved, must be clear to all concerned. These should be voiced during the actual resuscitation so that everyone involved knows what is intended, or which algorithm is being followed, or what is being prepared and anticipated.

6. Managing by measurement is another leadership strategy which, when translated into ED practice, dictates that the ultimate goal beyond a single resuscitation is to improve performance by learning from experiences, mistakes and successes. The only way to improve quality is to measure everything that is being done, so that this can be assessed and reflected upon to identify gaps, errors, and areas for improvement. The time taken to perform interventions, the sequence of events, all results, drug and defibrillator energy dosages should be recorded to help the team leader keep track of progress, and to document a detailed synopsis of the resuscitation for the clinical records. This is vital for meaningful review and research purposes.

7. In terms of feedback, remember to give the positive first, then the ‘negative’, followed by another positive once again. It is imperative that the team leader is an encouraging person, who is able to positively reinforce behaviour on the one hand while also easily able to correct poor performance in a constructive manner on the other. The effective team leader must embrace the role of mentor and coach, and engage in teaching during the resuscitation. All too often the team leader shouts and manages the process aggressively, being critical, insulting and humiliating. This is unprofessional and unnecessary, and is rather a reflection of the lack of competence and confidence of the team leader. Unless the team leader inspires and cheers the team on, teaches in a constructive way, and organizes the resuscitation in a quiet and controlled manner, they should not expect anybody to eagerly volunteer to participate in their resuscitations ever again!

8. To ensure effective teamwork, all team members need to feel safe enough to contribute meaningfully to the process. They must feel that there will be no retribution for offering input when they notice something awry, for asking a question, or for suggesting something that has been overlooked. It is only a mature and confident team leader who is able to receive advice or feedback from a more junior member of the team, especially when the team leader has made an error. Team leaders also make mistakes and are not infallible demigods (see Box 3.3)!

9. In the same way that ‘commentary driving’ is used in advanced driving courses, ‘commentary resuscitation’ can be practised in the ED. This is a technique that forces the team leader to concentrate and focus on what is happening at that instant, and then to verbalize and discuss it out loud. This is an excellent way to summarize and review the progress, including where the team is in the management process or on the algorithm, what has been done and what still needs to initiated. It allows those listening to hear the thoughts and thought processes of the team leader, and so is a powerful teaching tool. It further helps to structure the thoughts of the team leader, and so take control of what sometimes appears to be a runaway process.

10. Ideally, the management or resuscitation of every critically ill or injured child should embody the principles of action-centred leadership: the team leader has to simultaneously be aware of the needs of the group, each individual in that group, and the common task at hand. In order to succeed at the task (which is of supreme importance) both the requirements of the group and the individuals must be addressed. Each individual should be encouraged, coached and assisted to perform their tasks where necessary. Their contribution to the group effort should be acknowledged and welcomed. The team dynamic must be established and maintained.

Box 3.1 Simulation training for paediatric emergencies

The features that simulation offers which make it educationally sound are:

• Allows the chance for hands-on practice.

• Enables the trainer to provide immediate feedback as well as debriefing.

• Allows for practice to be done in a team environment.

• Errors are valued – they raise an awareness of where performance can be improved upon without the fear of poor outcomes or reprisal.

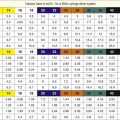

Box 3.2 Resuscitation aids in paediatric emergency care

• Assist in changing non-automatic thinking and decisions, with respect to drug dosage and equipment sizing, into automatic* processes so that critical thinking can be uninterrupted and dedicated to medical management.

• Eliminate the need for any calculations.

• Provide an accurate estimate of weight based primarily on length.

• Provide accurate guidance on resuscitation equipment.

• Provide accurate information on fluid therapy, bolus drug dosages, drug dilution and volumes to deliver.

• Provide accurate information on the preparation and delivery of drug infusions.

• Provide accurate information on initial ED ventilator settings.

• Provide useful age-linked reminders with regard to drug dosing, e.g. the need for relatively higher doses of suxamethonium in infants.

• Provide relevant information to every member of the team, e.g. not just a milligram drug dose for the doctor to order, but also instructions for the nurse on how to prepare and dilute the drug.

* This change is the foundation of resuscitation aids and is best explained by this analogy: when you start driving a car you have to think about everything – which pedals to push, which levers to pull, how to do every little thing. After a few years everything is done completely without thought, automatically and reflexively. Reading an instruction is automatic. Performing memory tasks and calculations is not. Thinking time needs to be spent where it is most needed – on patient management rather than trivial but essential distractors.