61 Lateral XLIF Fusion Techniques

Introduction

Demands of mobility and quality of life have increased in the elderly segment of society over the past decades. A rising number of elderly patients suffering from adult degenerative scoliosis may be eligible for surgical treatment.1 The prevalence of adult scoliosis rises with age: from 4% before age 45 years, to 6% at age 59 years, to 15% in patients older than 60 years.2

Adult scoliosis is defined as acquired deformity in the skeletally mature patient with a Cobb angle of at least 10 degrees in the coronal plane due to asymmetric disc and facet joint degeneration. It is associated not only with severe back and/or leg pain but also with complicated surgical outcomes.9

All nonoperative treatments should be exhausted before considering surgical treatment. Usually, the surgical procedure is focused on two aims. The first aim is to decompress the comprised neural elements in cases of symptomatic spinal stenosis, and the second is to balance and stabilize the spine in the coronal and sagittal planes when there is imbalance.4 Today a wide variety of approaches—anterior, posterior, or a combination—are available to achieve fusion, but all include significant operative morbidity.5 Newer implants have improved cosmesis and correction, obtaining better results; however, the elderly patient is not a candidate for this kind of surgery because of the higher risk of complications and generally poorer bone quality in this population.6

The eXtreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF) approach may offer various clinical advantages over more traditional techniques for treating adult degenerative scoliosis.7 This less invasive procedure realigns the endplates to a horizontal position through bilateral annular release, placement of a large implant across the disc space spanning the ring apophysis, and the effects of ligamentotaxis. The XLIF technique restores disc and foraminal heights, indirectly decompressing the neural elements, and promotes stabilization through an anterior intervertebral fusion stopping progression of the curve.

Clinical Study

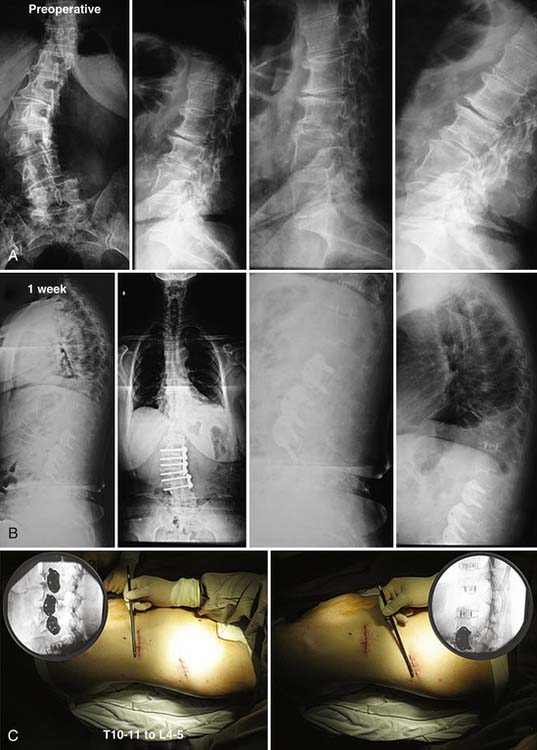

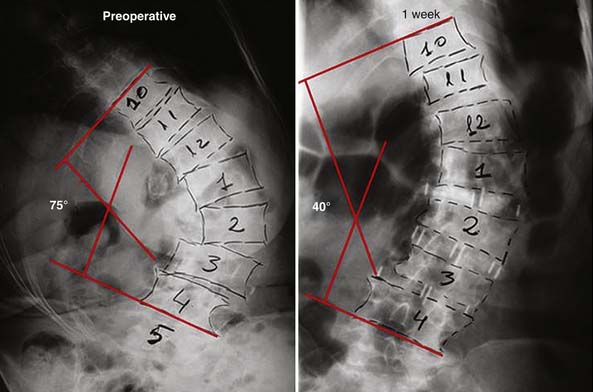

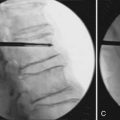

In a larger patient series, 23 patients have 3-year follow-up (FU). Mean age is 66 years (range, 39 to 88). Three to seven levels were treated between T10 to L5. Three of these needed lateral plate fixation (Figure 61-1).

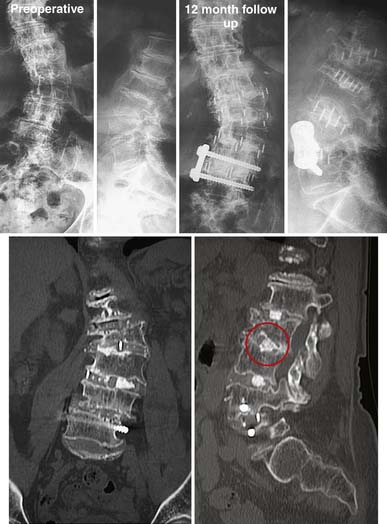

The procedures were performed without major complication in an average of 121 minutes and with <50 ml blood loss. Mean hospital stay was 40 hours. After 3-year FU, one patient (4%) presented with pseudarthrosis according to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) fusion criteria.7 Three patients (12%) had subsidence at 6-month FU, but all were asymptomatic. Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pain scores improved from an average of 8.1 preoperatively to 3.3 at 3-year FU.Oswestry scores improved from an average 47.8 preoperatively to 22.8 at 3-year FU. Coronal and sagittal alignments improved from average Cobb angles of 16 degrees preoperatively to 7.4 degrees at 3-year FU, and average lordosis angles of 37.8 degrees preoperatively to 48 degrees at 3-year FU. The mean preoperative Cobb angle was not high because in our earliest series we were not treating large curves. Currently, using the XLIF approach we can treat curves up to 90 degrees, with very good clinical results (Figure 61-2).

Preoperative Assessment and Planning

Operative Technique

Patient Positioning

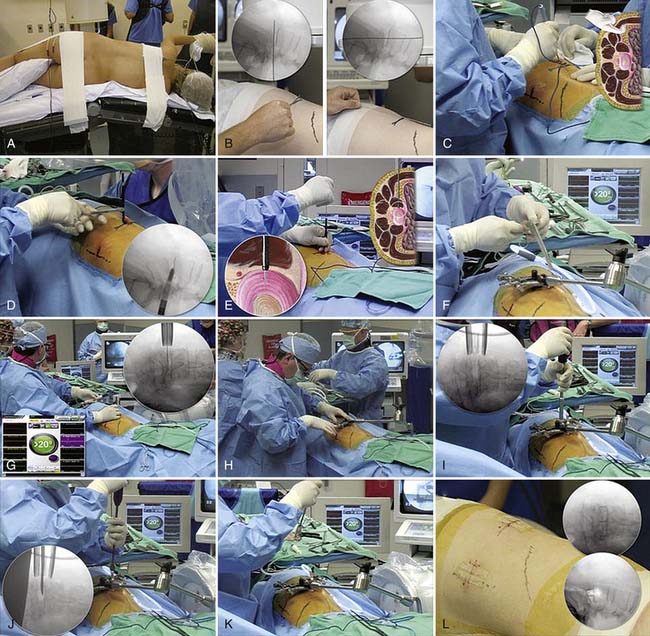

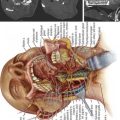

For the XLIF approach, the patient is placed and taped in a true 90- degree lateral decubitus position (Figure 62-3A), being preferable to approach from the concavity side. The table and/or patient should be laterally flexed to increase the distance between the iliac crest and the rib cage.

Incision and Retroperitoneal Access

The midposition of the disc of interest is identified using a Kirschner wire (K-wire) and fluoroscopy (Figure 61-3B). A small incision is created for insertion of the atraumatic tissue dilators and an expandable retractor (MaXcess, NuVasive, Inc., San Diego, Calif.), which will be the working portal. An incision posterior to this lateral marking is first made to introduce a finger into the retroperitoneal space to sweep open the space and ensure that all lateral attachments of the peritoneum are released to provide safe lateral entry (Figure 61-3C).

Transpsoas Access

With the retroperitoneal space identified, the finger is brought up under the lateral skin marking and an incision is made at this direct lateral location for the introduction of an initial dilator (Figure 61-3D). The finger in the retroperitoneal space is used to escort the dilator safely from the direct lateral incision to the psoas muscle. The dilator is then placed over the surface of the psoas muscle, exactly over the disc space to be treated, confirmed by fluoroscopy. The fibers of the psoas muscle are then gently separated with the dilators until the disc is reached (Figure 61-3E). The NeuroVision electromyographic (EMG) monitoring system (NuVasive, Inc.) assesses the proximity of the lumbar nerve roots to the advancing dilator (Figure 61-3G). An expandable retractor (MaXcess) is advanced over the last dilator (Figure 61-3F and H).

Under direct illuminated vision, a thorough diskectomy is performed using standard instruments (Figure 61-3I). The posterior and anterior annulus are left intact. The annulotomy window is centered in the anterior lateral half of the disc space. Disc removal and release of the contralateral annulus using a Cobb elevator (Figure 61-3J) provides the opportunity to place a long implant (Figure 61-3K) that will rest on both lateral margins of the apophyseal ring, maximizing endplate support, restoring height, and correcting imbalance alignment. Hemostasis is confirmed and no drains are required (Figure 61-3L).

Postoperative Care

Patients should be encouraged to walk the same day to aid their recovery and muscle function. Postoperative pain tends to be minimal, and may be discharged after only an overnight hospital stay.

Complications and Avoidance

In some series of adult deformity surgery, the complication rate is high, with elevated morbidity and mortality in some cases.8 In comparison, our results demonstrate a lower level of complications due to the minimally invasive nature of the procedure. We observed minor complications in the immediate postoperative period, such as tenderness with hip flexion on the operative side and less commonly, sensory disturbance in the operative side leg. Painful dysesthesias and motor disturbance are rare, but possible. In these cases, a CT scan is recommended to rule out a psoas hematoma. If a hematoma is found, draining it improves symptoms.

In the long-term FU, subsidence was observed in some cases, already described in the results (Figure 61-4).

Conclusion

The treatment for adult scoliosis differs from that for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.9 The most important issues are reduction of back and leg pain, and stop curve progression through fusion.10 The complication rate has been lower than traditional surgical methods of treatment. Subsidence is the most common complication in the XLIF stand-alone technique but our experience has shown no clinical compromise in the final result. We have been successfully performing fusion using stand-alone cages through a lateral minimal invasive approach, decreasing pain, decompressing indirectly neurological structures, restoring disc height and stopping the curve progression.

1. Schwab F., Dubey A., Gamez L., et al. Adult scoliosis: prevalence, SF-36, and nutritional parameters in an elderly volunteer population. Spine. 2005;30:1082-1085.

2. Y. Floman, Degenerative scoliosis: indications for surgery and results, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-British Volume, 88-B (Suppl.) 4–5.

3. Aebi M. The adult scoliosis. Eur. Spine J.. 2005;14:925-948.

4. Ploumis A., Transfledt E.E., Denis F. Degenerative lumbar scoliosis associated with spinal stenosis. Spine J.. 2007 Jul-Aug;7(4):428-436.

5. Gupta M.C. Degenerative scoliosis options for surgical management. Orthop. Clin. N. Am.. 2003;34:269-279.

6. Tribus C.B. Degenerative lumbar scoliosis: evaluation and management. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg.. 2003;11:174-183.

7. Ozgur B.M., Aryan H.E., Pimenta L., Taylor W.R. Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF): a novel surgical technique for anterior lumbar interbody fusion. The Spine Journal. 2006;6:435-443.

8. Bradford D.S., Tay B.K., Hu S.S. Adult scoliosis: surgical indications, operative management, complications, and outcomes. Spine. 1999;24:2617-2629.

9. Weiss H.R. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS)—an indication for surgery? A systematic review of the literature. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2008;30(10):799-807.

10. Daffner S.D., Vaccaro A. Adult degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Am. J. Orthop.. 2003;2:77-82.