CHAPTER 13 Lateral Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

Isolated lateral compartment, noninflammatory arthritis in a ligamentously stable knee with less than 10° of valgus and more than 90° of flexion is uncommon.

Isolated lateral compartment, noninflammatory arthritis in a ligamentously stable knee with less than 10° of valgus and more than 90° of flexion is uncommon.Introduction

Degenerative joint disease is a common diagnosis among adults, with an estimated prevalence of knee osteoarthritis ranging from 4.9% to 16.7%.1,2 Though difficult to pinpoint exactly, there has been an increase in the prevalence of osteoarthritis among adults in the United States.1 Patients often present with degeneration of multiple knee compartments, although the process can involve a single compartment. Laskin3 reported that less than 12% of patients in his practice had single-compartment disease and were candidates for unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA). Moreover, isolated lateral compartment arthritis is quite uncommon and has received little attention in the orthopaedic literature. Scott4 reported that lateral UKAs constitute less than 1% of all knee arthroplasties. Despite its low prevalence, the aging and increasingly active population ensures that orthopaedic surgeons will manage patients with isolated lateral knee compartment arthritis. For some of these, lateral UKA is a predictable solution.

Contraindications

Contraindications include advanced degenerative changes of the medial or patellofemoral compartments, inflammatory arthritic conditions, anterior cruciate or other ligament insufficiency, fixed valgus deformity or deformity greater than 10°, less than 90° of knee flexion, flexion contracture of greater than 10°, or a patient incapable of adhering to a post-arthroplasty lifestyle.5,6

Discussion

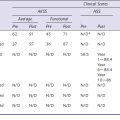

The potential benefits of UKA over TKA are faster recovery with shorter hospitalization and decreased morbidity, improved range of motion, better gait patterns, and bone conservation making future conversion to TKA easier should it be necessary.7–10 Reports in the literature on medial unicompartmental arthroplasty have shown promising results.11–14 Extrapolations of these data to the lateral compartment, however, may not be appropriate as it is quite different in terms of anatomic and biomechanical characteristics. There are limited studies that focus on the outcomes of lateral UKA.5,10,15–18 Marmor15 was the first to discuss unicompartmental arthroplasty for lateral compartment disease. He reported excellent results in 11 of 14 cases. Ohdera et al.16 reported good results in 16 of 18 patients with greater than 5 years’ follow-up. Ashraf et al.17 reported on 88 patients with an average of 9 years’ follow-up and felt that the results of lateral UKA were comparable to those found with medial UKA. Pennington et al.5 reported on 29 knees among which there were markedly improved Hospital for Special Surgery knee scores and no revisions at greater than 12 years after lateral UKA. Early and midterm data suggest current-design lateral UKA offers reliable results.5,10,16,17 As with any operative procedure, careful patient selection and adherence to proper indications and sound surgical technique influence these results. The remainder of this chapter reviews the preparation, surgical approach, technical factors, and postoperative management of lateral UKA.

Setup And Equipment

We utilize the same operating room setup as for a total knee replacement. The patient is positioned supine. A padded bump under the operative hip can be utilized at the surgeon’s discretion. A footrest or sandbag secured to the bed allows the knee to be flexed to 90° and beyond. Others drop the foot of the bed to use a suspended leg technique that allows hyperflexion of the knee.19–21 A well-padded tourniquet is positioned high on the thigh, with the lower extremity prepared and draped in a manner to allow the surgeon control of the extremity. The procedure is performed under tourniquet for modern cement technique and to improve visualization. Equipment will vary depending on the chosen implant. It is important to have a total knee system available in the event that intraoperative inspection reveals advanced degenerative changes affecting the medial or patellofemoral compartments. Likewise, preoperative counseling should include a discussion of the possibility for total knee arthroplasty. Other considerations include specialized retractors. We like to use a retractor in the notch that extends over the trochlea to protect the patellofemoral compartment. The need for these instruments is dependent on the chosen approach.

Surgical Approach (see Video 13-1)

Surgical Approach (see Video 13-1)

The lateral compartment can be easily accessed through a slightly lateralized oblique, extensile, paralateral incision running along the lateral border of the tibial tubercle and the patellar tendon (Fig. 13–1). A modified lateral parapatellar arthrotomy is then performed. There is some concern that this adds complexity in the event that conversion to a TKA is required or that future revision surgery will be more of a challenge. Sah and Scott6,18 reported this concern and described their technique for lateral UKA through a medial parapatellar approach. To provide another perspective, the lateral parapatellar approach has been quite successful in the senior author’s experience and has not posed problems intraoperatively or in the event of further surgery. The approach we describe provides excellent visualization of the surgical structures and minimizes soft tissue stripping.

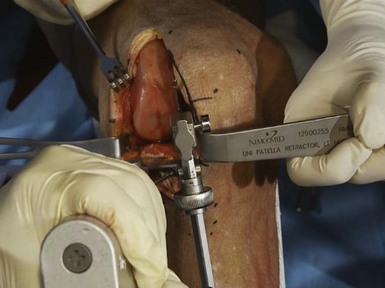

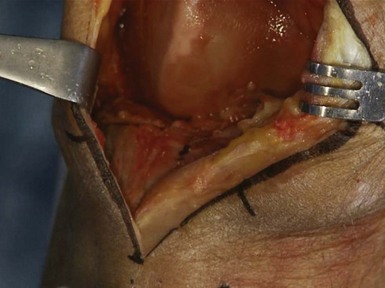

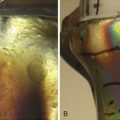

The skin incision is from the superior pole of the patella to just lateral to the tibial tubercle. The length of the incision is adjusted to allow for adequate visualization as needed. Skin flaps are full thickness but not excessively undermined. Once through the skin and subcutaneous fat, the arthrotomy proceeds through the retinaculum, staying lateral to the patellar tendon (Fig. 13–2). A moderate amount of fat is excised under the patellar tendon to allow for adequate visualization in determining tibial rotation. The lateral edge of the tibial plateau is exposed for visualization and to allow proper retractor placement by elevating a small portion of the iliotibial band off of Gerdy’s tubercle. The knee can be flexed and extended to allow visualization of the other compartments through this mobile soft tissue window. Final confirmation of isolated lateral disease is made prior to proceeding. Lateral femoral and tibial osteophytes should be removed. A patellar retractor is carefully placed after inspection of the anterior cruciate ligament to confirm its competence. A lateral Z retractor protects the iliotibial band and the lateral ligamentous and capsular structures after the visible portion of the lateral meniscus is excised.

Technical Description

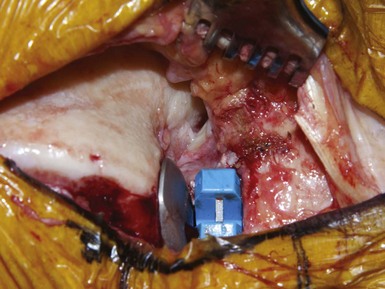

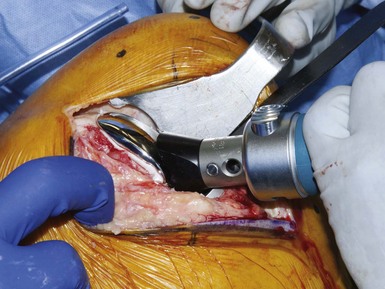

The exact steps of the procedure will vary depending on the chosen implant system, yet the principles are the same. We avoid mobile-bearing designs in the lateral compartment due to the risk of polyethylene dislocation.22 Ultimately, the goal is a measured resection of the distal femur and proximal tibia to allow for implantation of components with correction of the valgus deformity. Care must be taken not to overcorrect the knee and place undue stress on the medial compartment and lateral ligamentous structures as this may lead to accelerated wear of the medial compartment. Beginning with a “tibia-first” approach, an extramedullary alignment rod is utilized to perform a tibial resection adequate enough to accept the tibial component bearing surface. The flexion gap is usually a bit larger than that for a medial UKA due to the greater mobility of the lateral compartment. Coronal alignment should match the mechanical axis of the tibia and sagittal alignment should reproduce the natural posterior slope for each knee. A sagittal saw blade is utilized to make the initial cut vertical to the cutting block. This cut is in line with the medial border of the lateral femoral condyle and slightly internally rotated to account for the rotational relationship between the femur and tibia in full extension as a result of the “screw-home” mechanism. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the tibial insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament. The sagittal saw blade can be left in place to prevent undermining the anterior cruciate ligament tibial insertion while a standard saw blade is used to complete the tibial resection using the cutting block (Fig. 13–3). The resected tibial surface can assist in determining the appropriate tibial implant size. It is frequently shorter and wider than the resected tibia in a medial UKA due to the configuration of the lateral tibial plateau.

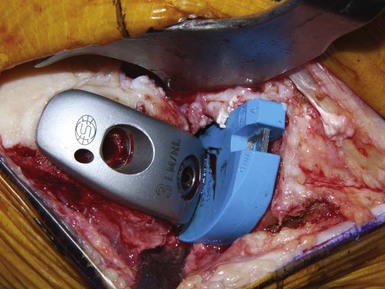

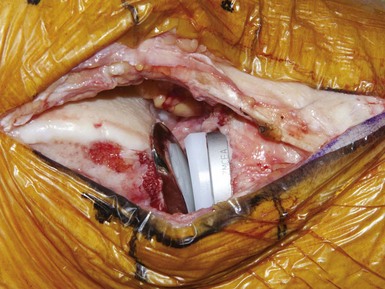

Distal femoral resection is accomplished by implant-specific techniques but is performed to result in equal flexion and extension gaps. It is important to note that balancing the flexion and extension gaps is accomplished on the femoral side, most notably on the distal femoral cut as the posterior cut is usually a measured resection specific to the implant. After measuring the flexion gap, the extension gap is cut in a manner to allow for the same-size spacer block to fit as comfortably as that used in flexion. In comparison with a medial UKA, this feel is slightly looser. Our preferred system utilizes the cut tibial surface to assist in alignment with the knee in extension. After the distal femoral resection is complete, a 2-in-1 cutting block is utilized to perform the posterior condylar and posterior chamfer cuts. Posterior femoral osteophytes are then removed, and the remaining meniscal tissue is excised. A femoral trial implant is selected to ensure adequate surface coverage without extending too anteriorly, which risks inappropriate articulation of the component with the patella. The cut tibial surface is likewise measured and a trial placed. The knee should move naturally through a range of motion without increased laxity or limitations to flexion and extension (Fig. 13–4). Stability is checked in full extension, 30° of flexion, midflexion, and finally full flexion (Fig. 13–5). Sagittal plane stability should also be confirmed. It is important to check motion and stability with retractors removed to allow for a true representation of ligament tension.

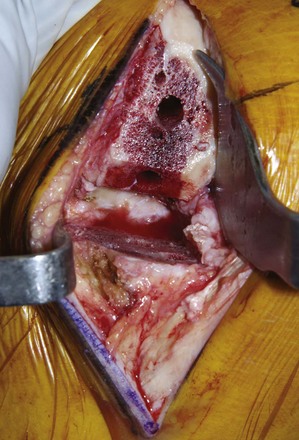

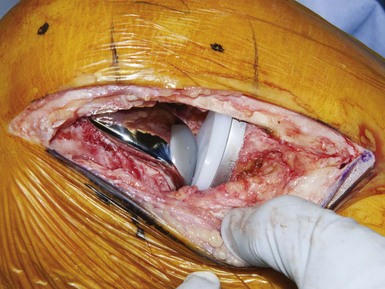

Once satisfied with the construct, peg holes or keels can be prepared as per manufacturer recommendations, leaving the bone surfaces fully prepared for implantation (Fig. 13–6). The knee should be copiously irrigated with pulsatile lavage after areas of sclerotic subchondral bone are drilled with a small-diameter bit to improve cement interdigitation. A moistened surgical sponge placed with a tonsil forceps peripheral to the cut tibial surface aids in preventing retained lateral or posterior excess cement. With retractors positioned, the tibial implant is placed first. Cement technique is critical at this juncture as extruded posterior cement is difficult to retrieve with implants in place. It helps to place the posterior portion of the implant in first, then compressing it anteriorly so as to force the cement into the tibia and out anteriorly (Fig. 13–7). Extruded tibial cement is removed, as is the sponge. The femoral component is placed with a plastic tongue depressor sitting over the tibial baseplate to protect the femur from scratching (Fig. 13–8). We prefer an implant with femoral lugs that allow compression of the posterior condylar cement. Again, excess cement is removed and the polyethylene liner impacted into the tibial tray if using a modular design. The knee should be held in extension to slight flexion until the cement is hardened to prevent the tibial component from lifting up anteriorly. Final inspection of the implant should ensure normal knee motion and stability without patellar impingement (Figs. 13–9 and 13–10).

Special Considerations

The unicompartmental arthroplasty of the lateral compartment is technically quite different than that of the medial compartment.23 One of the more critical concepts unique to lateral UKA is the rotation of the tibial component. There is a tendency to introduce too much external rotation when preparing the tibia. The tibial resection is made with the knee flexed. As the knee extends, there is a relative external rotation of the tibia with respect to the femur. This screw-home mechanism results from the complex anatomy of the knee and the coupling of the cruciate ligaments.24 Moglo and Shirazi-Adl24 found the tibia to rotate internally 16.4° in 90° of knee flexion and externally 1.3° in knee hyperextension. If this tibial rotation is not taken into account during bone preparation, the tibial component will be externally rotated relative to the femoral component, causing edge loading of the polyethylene (Fig. 13–11). Pennington et al.5 identified this unique aspect of lateral unicompartmental replacements and offer recommendations on how to avoid it. Essentially, the key is in the rotation of the tibial implant, which must be accounted for when performing the tibial resection.5 By setting the tibial cutting guide in the appropriate alignment in flexion, the surgeon first ensures proper coronal plane alignment and reproduction of the posterior tibial slope. The vertical cut can be initiated after checking the orientation of this cut in full extension (Fig. 13–12). This will allow a better matching of the femoral condyle throughout the range of motion. If necessary, the femoral component can be lateralized slightly as well to improve articulation with the tibia.6 However, if the articulation is significantly off in extension such that there is edge loading of the implants, the likely problem is the tibial rotation. Though unproven in the literature, abnormal implant articulation likely would diminish the survival of the implant.

Postsurgical Management

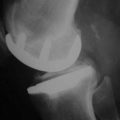

Interdisciplinary management from pain management services, physical and occupational therapy, and case management allows for rapid recovery. Patients are allowed immediate weight bearing under the supervision of physical therapy. Peripheral nerve catheters managed by anesthesia specialists are quite helpful in promoting adequate pain control to accommodate a rapid recovery protocol. Such protocols facilitate early mobility and decrease length of hospital stay.25 Patients are hospitalized overnight and typically released home on the first or second postoperative day when deemed appropriate by the multidisciplinary team (Figs. 13–13 and 13–14). Prophylaxis against venous thromboembolic events includes early mobilization and sequential compression devices. Most patients also receive aspirin 325 mg twice daily for 4–6 weeks. High-risk individuals are discharged on enoxaparin rather than aspirin at the discretion of the surgeon. Assistive devices are used for ambulation as required. Outpatient physical therapy concentrates on gait training, strengthening, proprioception, and range of motion. Initial follow-up in the office occurs 2–4 weeks after surgery. The ability for a patient to return to work is dependent upon job description and demands but can be quite soon for many office-type jobs.

Tips and Pearls

1 Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26-35.

2 Grotle M, Hagen KB, Natvig B, et al. Prevalence and burden of osteoarthritis: results from a population survey in Norway. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:677-684.

3 Laskin RS. Unicompartmental knee replacement: some unanswered questions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:267-271.

4 Scott RD. Lateral unicompartmental replacement: a road less traveled. Orthopedics. 2005;28:983-984.

5 Pennington DW, Swienckowski JJ, Lutes WB, Drake GN. Lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: survivorship and technical considerations at an average follow-up of 12.4 years. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:13-17.

6 Sah AP, Scott RD. Lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty through a medial approach: surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2008;90(Suppl 2 Pt 2):195-205.

7 Laurencin CT, Zelicof SB, Scott RD, Ewald FC. Unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty in the same patient: a comparative study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;273:151-156.

8 Rougraff BT, Heck DA, Gibson AE. A comparison of tricompartmental and unicompartmental arthroplasty for the treatment of gonarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;273:157-164.

9 Chassin EP, Mikosz RP, Andriacchi TP, Rosenberg AG. Functional analysis of cemented medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:553-559.

10 Volpi P, Marinoni L, Bait C, et al. Lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: indications, technique and short-medium term results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1028-1034.

11 Murray DW, Goodfellow JW, O’Connor JJ. The Oxford medial unicompartmental arthroplasty: a ten-year survival study. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1998;80:983-989.

12 Argenson JN, Chevrol-Benkeddache Y, Aubaniac JM. Modern unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with cement: a three to ten-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2002;84:2235-2239.

13 Berger RA, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ, et al. Results of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty at a minimum of ten years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2005;87:999-1006.

14 Price AJ, Waite JC, Svard U. Long-term clinical results of the medial Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;435:171-180.

15 Marmor L. Lateral compartment arthroplasty of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:115-121.

16 Ohdera T, Tokunaga J, Kobayashi A. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for lateral gonarthrosis: midterm results. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:196-200.

17 Ashraf T, Newman JH, Evans RL, Ackroyd CE. Lateral unicompartmental knee replacement survivorship and clinical experience over 21 years. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2002;84:1126-1130.

18 Sah AP, Scott RD. Lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty through a medial approach: study with an average five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2007;89:1948-1954.

19 Price AJ, Webb J, Topf H, et al. Rapid recovery after Oxford unicompartmental arthroplasty through a short incision. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:970-976.

20 Romanowski MR, Repicci JA. Minimally invasive unicondylar arthroplasty: eight-year follow-up. J Knee Surg. 2002;15:17-22.

21 Bonutti PM, Neal DJ, Kester MA. Minimal incision total knee arthroplasty using the suspended leg technique. Orthopedics. 2003;26:899-903.

22 Robinson BJ, Rees JL, Price AJ, et al. Dislocation of the bearing of the Oxford lateral unicompartmental arthroplasty: a radiological assessment. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2002;84:653-657.

23 Romanowski MR, Repicci JA. Technical aspects of medial versus lateral minimally invasive unicondylar arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2003;26:289-293.

24 Moglo KE, Shirazi-Adl A. Cruciate coupling and screw-home mechanism in passive knee joint during extension–flexion. J Biomech. 2005;38:1075-1083.

25 Klika AK, Gehrig M, Boukis L, et al. A rapid recovery program after total knee arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplasty. 2009;20:40-44.

Laurencin CT, Zelicof SB, Scott RD, Ewald FC. Unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty in the same patient: a comparative study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;273:151-156.

Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26-35.

Marmor L. Lateral compartment arthroplasty of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:115-121.

Ohdera T, Tokunaga J, Kobayashi A. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for lateral gonarthrosis: midterm results. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:196-200.

Pennington DW, Swienckowski JJ, Lutes WB, Drake GN. Lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: survivorship and technical considerations at an average follow-up of 12.4 years. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:13-17.

Romanowski MR, Repicci JA. Technical aspects of medial versus lateral minimally invasive unicondylar arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2003;26:289-293.

Rougraff BT, Heck DA, Gibson AE. A comparison of tricompartmental and unicompartmental arthroplasty for the treatment of gonarthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;273:157-164.

Sah AP, Scott RD. Lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty through a medial approach: study with an average five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2007;89:1948-1954.

Sah AP, Scott RD. Lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty through a medial approach: surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2008;90(Suppl 2 Pt 2):195-205.

Volpi P, Marinoni L, Bait C, et al. Lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: indications, technique and short-medium term results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1028-1034.