Chapter 38 Lateral pharyngoplasty

1 INTRODUCTION

We call lateral pharyngoplasty (LP) the surgical splint of the lateral pharyngeal walls, achieved by turning the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscles (SPC) into dilating flaps. The lateral pharyngeal muscular walls are thickened and exceedingly collapsible during respiration in patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome, causing narrowing of the pharynx. The SPC muscles envelop all the collapsible segment of the pharynx and form the outer pharyngeal muscular layer.

3 SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

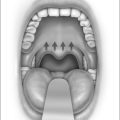

The procedure is performed with the patient under general anesthesia, using a mouth gag with a long tongue blade to give adequate exposure (Fig. 38.1). We use 4.0 Vicryl for all sutures. LP is performed as a stand-alone treatment for snoring and sleep apnea. When the patient needs nasal surgery to improve nasal breathing, this can be done in combination with LP. Fourteen per cent of our cases were treated with both LP and nasal surgery together.

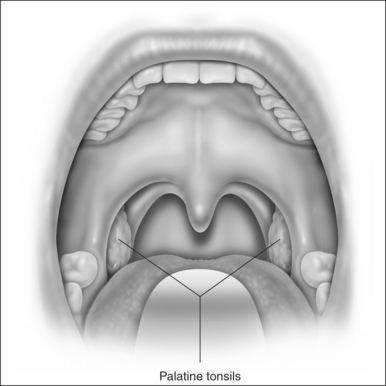

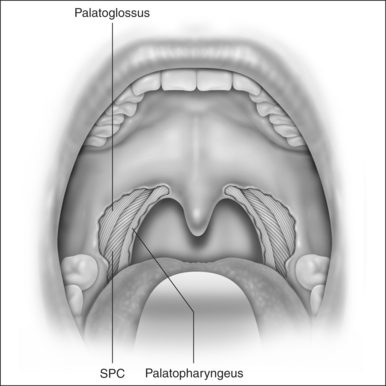

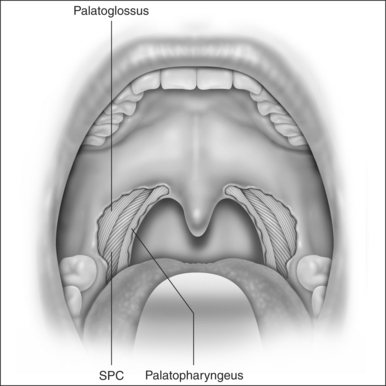

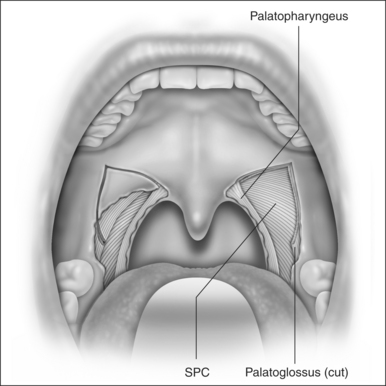

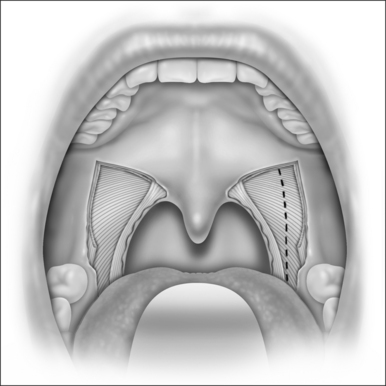

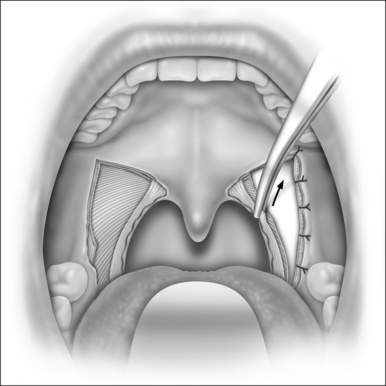

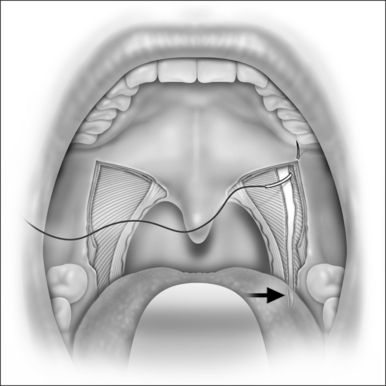

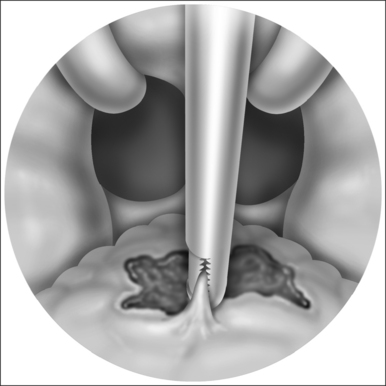

LP starts with a bilateral tonsillectomy (Fig. 38.2). If that has already been done, we undermine and remove the tonsillar fossa lining until we can identify the palatoglossus and palatopharyngeus muscles. Next, with an upside down ‘V-shape’ incision (Fig. 38.3), we remove a triangle of mucosa and muscle (palatoglossus) from the lateral oral free margin of the soft palate and anterior pillar.That provides a wide exposure of the SPC muscle, including its pterygopharyngeal (partially), buccopharyngeal and mylopharyngeal parts (Figs 38.4 and 38.5). The height of this incision corresponds to that reached by the lateral superior traction (see Fig. 38.10) of the upper part of the palatopharyngeus muscle, which will be used to close this wound.

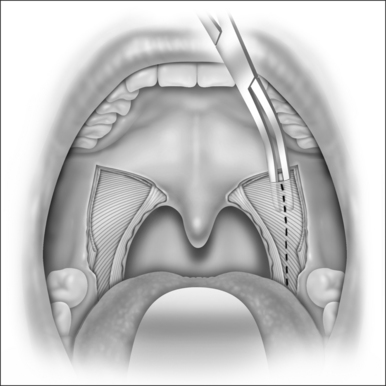

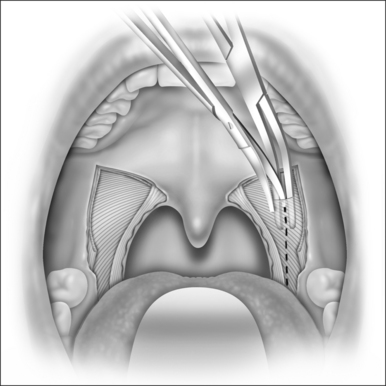

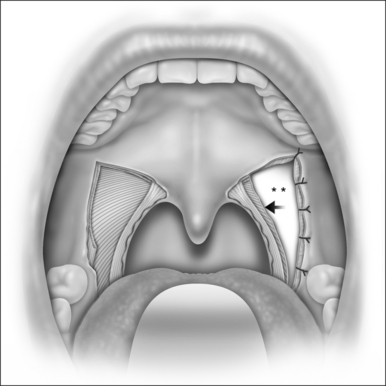

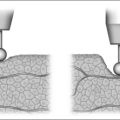

Once fully exposed, we undermine and elevate the SPC muscle from the peripharyngeal space (Fig. 38.6), starting from its most cranial visible part, and separate it from its fascia (buccopharyngeal fascia). It is very important to preserve this fascia, avoiding injury to cranial nerves IX and X and to other pharyngeal muscles, which could delay swallowing recovery. The SPC muscle is elevated from the pharyngeal wall in its posterior but not lateral aspect, near the palatopharyngeus muscle, since this region has fewer blood vessels, and once you reach the right plane of dissection there, the muscle can be easily detached from its fascia. Usually, the vertical fibers of the palatopharyngeus muscle have to be pulled medially at the start of the dissection, to expose better the horizontal fibers of the SPC. Once detached, we cauterize the SPC with a bipolar and section its fibers in a cranial to caudal direction (Fig. 38.7). We keep this dissection near the palatopharyngeus, using this muscle as a guide to avoid injuring vessels and nerves at the lateropharyngeal space. This dissection extends as far as the caudal end of the SPC muscle (glossopharyngeal part, where it originates from the side of the tongue). To accomplish this, we have to create a submucosal tunnel inferiorly to the tonsillar fossa to preserve and separate the mucosa from the SPC muscle that is being sectioned. This usually extends from 1 to 1.6 cm beyond the tonsillar fossa, depending on the anatomy, and relates to the retroglossal area.

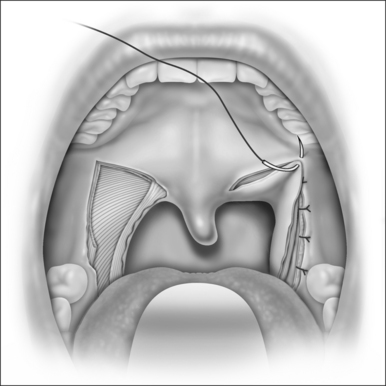

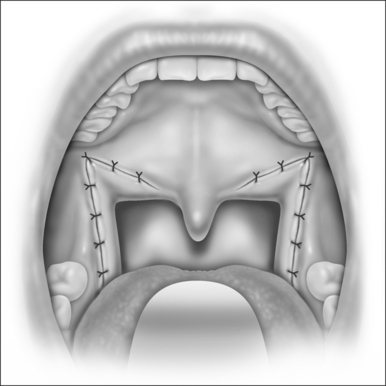

When the section of the SPC is complete, we get two muscle flaps: one medially based flap that is not manipulated any further, and one laterally based flap that is sutured anteriorly to the same-side palatoglossus muscle with four or five separate stitches (Fig. 38.8). The glossopharyngeal part of the SPC does not need to be sutured. At the end of this suturing line, the peripharyngeal space is widely exposed and the lateral wall is splinted along all of the collapsible pharynx (Fig. 38.9). This surgical wound is then closed by pulling and suturing the palatopharyngeus to the remnants of the palatoglossus muscle (Figs. 38.10 and 38.11). The medial flap of the SPC is not included in this pull. Every step is then repeated on the opposite side (Fig. 38.12). At the end, due to the bilateral pull of the palatopharyngeus muscles, the uvula stays in the midline and sometimes it bends upwards, returning to normal within hours or days.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Mr J. Falcetti from Arte e Comunicação Médica for the illustrations.

Cahali MB. Lateral pharyngoplasty: a new treatment for obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1961-1968.

Cahali MB, Formigoni GGS, Gebrim EMMS, Miziara ID. Lateral pharyngoplasty versus uvulopalatopharyngoplasty: a clinical, polysomnographic and computed tomography measurement comparison. Sleep. 2004;27(5):942-950.

Friedman M, Tanyeri H, La Rosa M, et al. Clinical predictors of obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1901-1907.

Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Bass L. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:13-21.

Isono S, Remmers JE, Tanaka A, et al. Static properties of the passive pharynx in sleep apnea. Sleep. 1996;19(Suppl):S175-sS177.

Li KK, Guilleminault C, Riley RW, Powell NB. Obstructive sleep apnea and maxillomandibular advancement: an assessment of airway changes using radiographic and nasopharyngoscopic examinations. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:526-530.

Morrison DL, Launois SH, Isono S, et al. Pharyngeal narrowing and closing pressures in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:606-611.

Schellenberg JB, Maislin G, Schwab RJ. Physical findings and the risk for obstructive sleep apnea: the importance of oropharyngeal structures. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:740-748.

Schwab RJ, Gefter WB, Hoffman EA, et al. Dynamic upper airway imaging during awake respiration in normal subjects and patients with sleep disordered breathing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1385-1400.

Schwab RJ, Gupta KB, Gefter WB, et al. Upper airway and soft tissue anatomy in normal subjects and patients with sleep-disordered breathing: significance of the lateral pharyngeal walls. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1673-1689.

Schwab RJ, Pack AI, Gupta KB, et al. Upper airway and soft tissue structural changes induced by CPAP in normal subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1106-1116.

Winter WC, Gampper T, Gay SB, Suratt PM. Lateral pharyngeal fat pad pressure during breathing. Sleep. 1996;19(Suppl):S178-S179.

Woodson BT, Wooten MR. Manometric and endoscopic localization of airway obstruction after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:38-43.