Lateral Ligament Repair of the Ankle

Robert Donatelli, Will Hall, Brian E. Prell, Graham Linck and Richard D. Ferkel

The ankle requires both static and dynamic stability. Mobility is crucial for normal ankle function in the midst of rapidly changing postures of the foot during sporting and everyday weight-bearing activities. Lateral ligament injuries of the ankle account for 13% to 56% of all injuries in sports requiring running or jumping such as soccer, basketball, and volleyball.1,2 Ankle sprains also compromise 10% of the emergency room visits in the United States, with an incidence of 30,000 injuries per day.3 The large majority of these injuries can be successfully treated conservatively with casting, bracing, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and physical therapy. Approximately 85% of all ankle sprains involve the lateral structures of the ankle.4,5 The majority of ankle sprains heal without any residual functional instability.4 Despite adequate trials of conservative measures, however, approximately 10% to 30% of all acute ligamentous injuries have recurrent symptoms of chronic pain, swelling, and instability with activities.4,6–9 Functional instability of the ankle is reported to be as high as 20% after ankle sprains.10,11 Ligamentous instability has been thought to be related to the loss of mechanoreceptors12 and can lead to the development of ankle joint degenerative changes.13 When conservative measures fail to produce satisfactory proprioceptive performance and mechanical stability, surgical repair or reconstruction of the injured lateral ligament structures should be considered.

Anatomy and Mechanism of Injury

The etiology of the unstable ankle is usually a forced plantar flexion inversion injury in which the body’s center of gravity rolls over the ankle. This type of force results in injury to the anterior talofibular (ATF) ligament; and possibly the calcaneofibular (CF) ligament, the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, or the posterior talofibular (PTF) ligament.3 The ATF ligament is the weakest of the lateral ligaments and blends with the ankle joint capsule. The CF ligament is the only extraarticular ligament among the complex and is larger and stronger than the ATF ligament14; it has been found able to withstand forces two to three-and-a-half times greater than that of the ATF ligament.15 The PTF ligament is the strongest of all the ligaments and is rarely injured with inversion sprains or associated with chronic ankle instability.14 The unstable ankle is generally caused by a traumatic event such as an ankle sprain. It also can be associated with ankle fractures but virtually never develops insidiously.

Surgical Indications and Considerations

A lateral ankle reconstruction is an elective surgery used to treat chronic instability that results from a continuum of ankle injuries. Ankle injuries can result in permanent damage to the ligaments that support the lateral ankle. Various studies have examined the benefits of surgical versus functional treatment in lateral ligament injuries of the ankle. These studies have shown that operative repair was associated with patients’ delayed return to work, restricted range of motion (ROM), impaired ankle mobility, and increased complications after surgery, including undefined pain.16–19 This is in contrast to conservative treatment, which includes functional bracing and early mobilization. Kannus and Renstrom reviewed 12 prospective studies and found that functionally or conservatively managed patients with grade III ankle sprains returned to work two to four times faster than those patients who underwent acute repair of the damaged ligaments.20 Therefore, the surgical option is used when nonoperative treatments have failed, such as physical therapy, bracing, activity modification, and steroid injections. Postoperative physical therapy is a vital link in returning the patient to an active lifestyle.

Indications for reconstruction of the ankle’s lateral ligaments include recurrent giving way with activities of daily living (ADLs) and sports that is refractory to conservative treatment, a positive physical examination, abnormal inversion, and/or positive anterior drawer stress x-rays (Fig. 28-1).

Patients of all ages and types are candidates for this type of surgery, but few patients older than 50 years undergo ankle reconstruction because of decreased activity levels and an increased ability to adjust functions and lifestyle to avoid recurrent buckling episodes. Surgeons should take care when considering this procedure for patients with generalized ligamentous laxity and collagen disorders that may result in failure. In addition, advanced degenerative joint disease or arthrofibrosis may be relative contraindications to this surgery.

Surgical Procedures

More than 50 different surgical procedures for correction of lateral ankle instability have been described.21 The majority of reconstructive procedures use part, or all, of the peroneal brevis tendon. Common procedures include the Watson-Jones, Evans, Chrisman-Snook, and Elmslie procedures and their modifications. Anatomic repair with direct suturing of the torn ligaments, imprecation, reinsertion to the bone, and in some instances augmentation with local tissue have increased recently in popularity.10,22,23 Direct repair of the ATF and CF ligaments was described by Broström in 1966 and later modified by Gould in 1980.22,24 Direct repair of torn lateral ligaments has the advantage of being simple and reliable, avoiding the use of normal tendons. It restores the original anatomy, requires less exposure, and maintains full ankle motion.

Procedure—Modified Broström

The modified Broström procedure, also termed the Broström-Gould procedure, is the method of choice for most patients with lateral ankle instability. The patient is taken to the operating room and examined under anesthesia. If the surgeon has any questions about the degree of ankle instability, stress x-ray films (stressing the ankle in both inversion and anterior drawer) are taken. The thigh is then secured on a well-padded thigh holder in preparation for ankle arthroscopy, as described in Chapter 30. The lower extremity is prepared and draped in standard fashion. Arthroscopy is performed first; the authors of this chapter have found that 93% of patients have additional intraarticular ankle pathology associated with lateral ankle instability in one study.5 More recently, in another study, we found 95% of patients had associated intraarticular problems noted at arthroscopy before the Broström procedure.25 In addition, a similar report by Taga showed 95% of patients have additional intraarticular pathology at the time of ankle reconstruction.26 Hua and associates27 found 91% of patients to have intraarticular lesions at the time of the modified Broström reconstruction.

The intraarticular pathology is identified and addressed through arthroscopic surgery. The scarred anterior talofibular (ATF) ligament is identified and assessed to make sure it is adequate for the modified Broström repair. After the arthroscopy is completed, the nurse removes the thigh support and places the leg flat on the surgical table. The ankle is reswabbed with a sterile antibacterial solution. An additional clean surgical drape is placed over the foot and ankle, and gloves are changed. New sterile instruments are used to perform the open portion of the procedure. Arthroscopic methods are now available for surgical reconstruction of the lateral ankle ligaments, but at this time open stabilization as described by Broström gives a better, more reproducible result. Recently, Corte-Real and Moreira,11 Lui,28 Nery and associates29 reported on their arthroscopic method for chronic lateral ankle instability. The results had a high percentage of good-excellent results, but long-term studies are necessary to compare the arthroscopic with the open procedures before a recommendation can be made for switching to all-arthroscopic techniques.

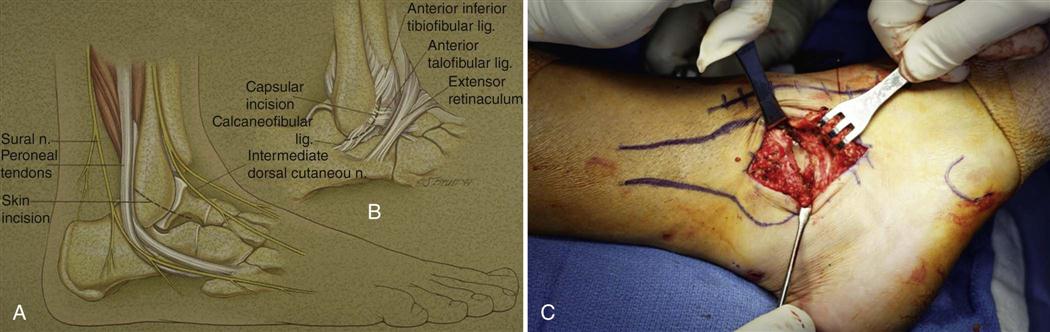

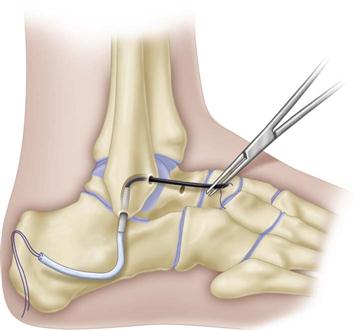

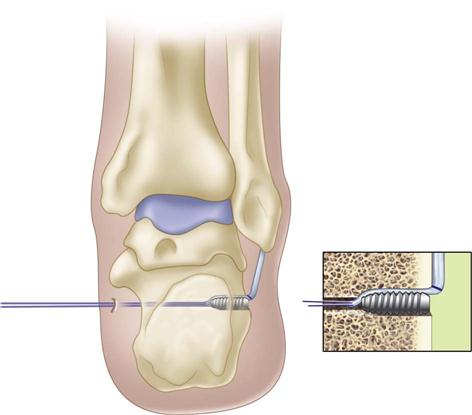

After arthroscopy the ankle is prepared and the tourniquet inflated. An incision is made over the lateral aspect of the ankle. This incision may be obliquely shaped in the skin folds or more vertical from the fibula toward the sinus tarsi, depending on the surgeon’s preference and the clinical situation. The senior author prefers the vertical incision because it allows better assessment of the peroneal tendons and can be extended distally and proximally if other procedures need to be done. Dissection is carried down through the subcutaneous tissues and the extensor retinaculum is carefully exposed because it is to be used for later reattachment. The surgeon must take care to avoid the intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerve, the lateral branch of the superficial peroneal nerve (which often lies near the end of the ATF ligament), and the sural nerve (which lies over the peroneal tendons). An oblique capsular incision is then made along the anterior border of the fibula from the AITF ligament to the CF ligament, leaving a small 3- or 4-mm cuff of tissue on the fibula for reattachment of the torn ligament complex (Fig. 28-2). The stretched ATF ligament is found as a thickening in the anterior capsule, and the CF ligament is found in the distal portion of the wound under the tip of the fibula, running deep to the peroneal tendons. The CF ligament often is attenuated or avulsed from the fibular tip.

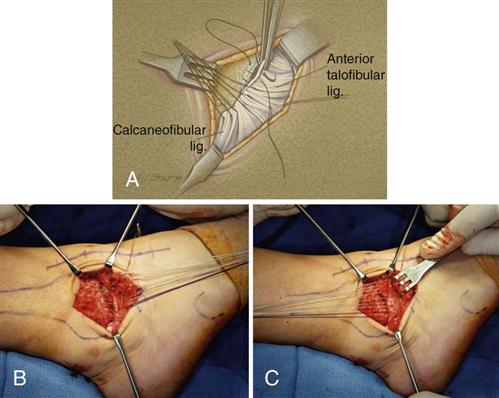

A “pants-over-vest” overlapping suture technique is used to imprecate or shorten the torn ligaments and provide a double layer of reinforcement to the repair. Suturing is done starting from the ligament portion attached to the talus, so that the knots are tied distal and inferior to the fibula (Fig. 28-3). This helps prevent postoperative knot prominence and skin irritation with shoe wear. “O” nonabsorbable sutures are used in the majority of the repair, but one absorbable suture is used for the CF ligament near the peroneal tendon, to avoid irritation. The sutures are tied with the ankle in neutral position, and a posterior drawer is applied to reduce the talus. The ankle is checked to make sure full ROM has been maintained during the repair. The extensor retinaculum is then pulled proximal over the repair and sutured to the fibular periosteum. ROM is again checked, as is the stability of the ankle. The tourniquet is released, and bleeding tissues are coagulated. The subcutaneous tissue and skin are then closed in the standard fashion. The patient is placed in a short-leg well-padded cast that is split in the recovery room to allow for swelling.

The patient’s cast is changed at 1 and 2 weeks and the stitches are removed. Weight bearing is started at week 3 in a cast or cast boot, at the surgeon’s discretion. Physical therapy with mobilization starts usually at week 6 or sometimes sooner.

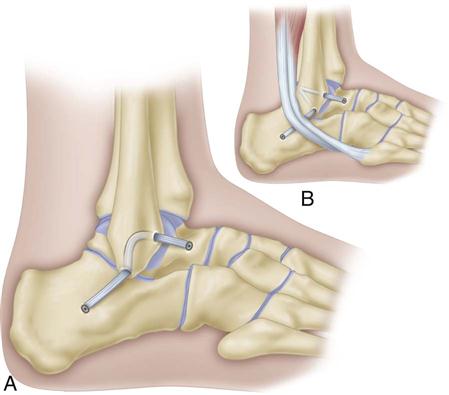

Procedure—Anatomic Hamstring Reconstruction

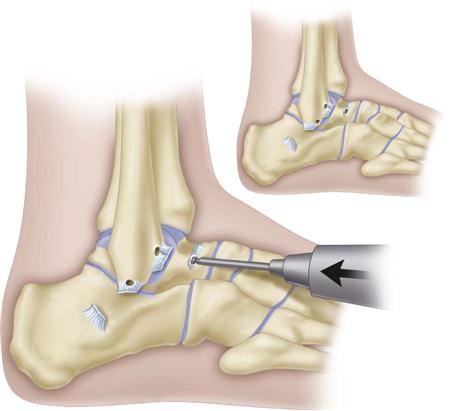

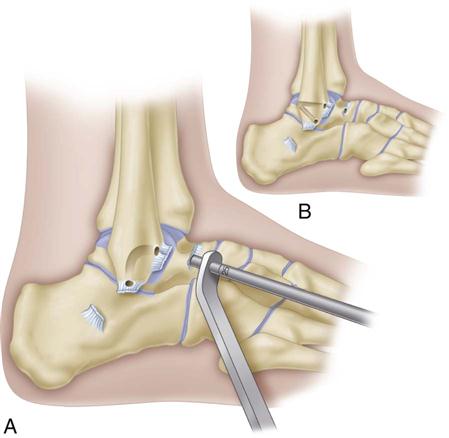

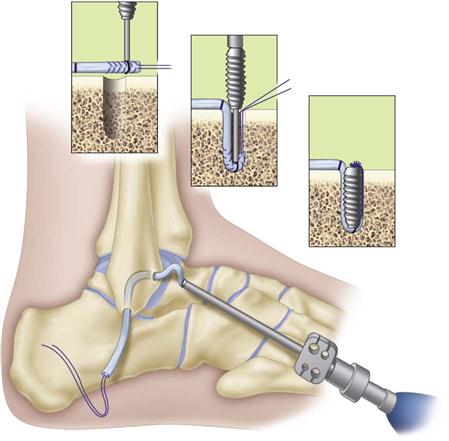

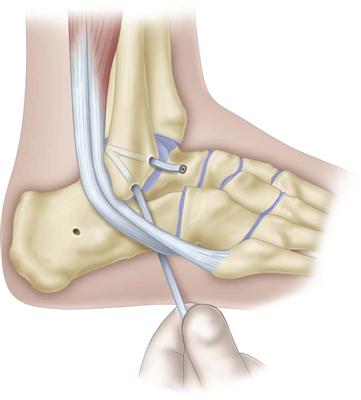

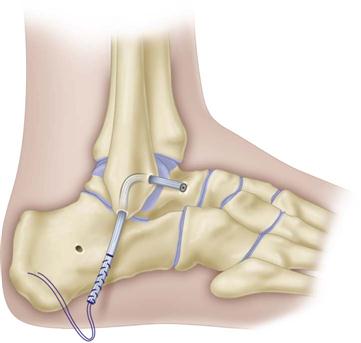

Indications for an anatomic hamstring reconstruction include a high-stress, heavy athlete, generalized ligamentous laxity, deficient ATF ligament tissue for direct repair, talar tilt greater than 10o more than the opposite ankle, and a varus hindfoot. The incision used is the same as shown in Fig. 28-2, A. The lateral ligaments are released in the same oblique fashion for later reattachment over the hamstring repair. An autogenous or allograft semitendinosus graft is prepared with nonabsorbable sutures at both ends. A guidepin is inserted into the fibula to create two converging bony tunnels, beginning from insertion of the ATF ligament on the fibula, as well as the insertion of the CF ligament on the fibula. These tunnels are connected using a curved curette. Alternatively, as option B, the holes can be drilled out the posterior fibula to increase the bone bridge between the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) arm and the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) arm. A reamer is then placed over the guidepin to create 5-mm tunnels. A guidepin is then inserted along the talar neck at the nonarticular portion and reamed to a predetermined size based on the diameter of the graft (Figs. 28-4 and 28-5). A passing device is placed from posterior to anterior through the fibula to facilitate graft passage (Fig. 28-6). The graft is then fixated on the talus with a special interference screw that helps push the tendon into the bone socket (Fig. 28-7). Alternatively, in option B, the graft can be passed from anterior to posterior and the ATF arm can be separately tensioned and fixed with an interference screw before tensioning the CFL arm (Fig. 28-8). This is usually done in slight plantar flexion because this is when the ATF ligament is the tightest. The tensioning on the CFL arm is done in slight dorsiflexion, and the tendon is passed underneath the peroneal tendons to exit into a drill hole made through the calcaneus. The CFL arm is cut so that 20 mm of the tendon will be in the calcaneus when it is secured with an interference screw (Fig. 28-9). This is done with the ankle in neutral position by bringing the sutures out through a poke hole on the medial heel and pulling tension on the sutures while the screw is inserted in the calcaneus (while pulling the graft into the tunnel) (Fig. 28-10). The final constructs gives anatomic reconstruction of the ATFL and CFL (Fig. 28-11). A modified Broström repair is then done over the hamstring reconstruction.

The patient is then placed in a cast which is split in the recovery room. The cast is changed at 1 and 2 weeks, and the stitches removed. Weight bearing is started at week 3 in a cast or a cast-boot at the surgeon’s discretion. Physical therapy usually starts in the pool at week 6 or 8, depending on what else is done at surgery.

Surgical Outcomes

A lateral ankle reconstruction is considered to be successful when the patient has full ROM and a pain-free ankle and can return to all ADLs and sports without restriction. Liu and Baker30 studied the static restraints of various surgical procedures in 40 cadaveric ankles. They found no significant difference between the Watson-Jones and Chrisman-Snook procedures, but the modified Broström procedure produced the least anteroposterior displacement and talar tilt at all different forces tested.

Hennrikus31 prospectively compared the Chrisman-Snook and modified Broström procedures in 40 patients. Although both produced 80% good-to-excellent results, the former procedure had a much greater proportion of complications and the latter procedure had a higher functional score. Hamilton et al34 performed the modified Broström procedure on 28 ankles; 54% of the patients were high-level ballet dancers. At 64 months’ follow-up, he noted 27 of 28 good-to-excellent results. Peters33 reviewed the literature and found 460 ankles treated with anatomic modified Broström repairs had an average of between 87% and 95% good-to-excellent results.

Ferkel and Chams25 reviewed the results of 21 patients who underwent the modified Broström procedure. The average patient age was 27.5 years and the average follow-up occurred at 57 months. They found 95% good-to-excellent results with an American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society’s (AOFAS) ankle/hindfoot score of 97.1. When the ATF ligament is not adequate to use for a Broström repair, we use either an autogenous or allograft hamstring graft with biotenodesis screws through the talus and calcaneus to reconstruct the ATFL and CFL.34–36

Alternatively, the Broström-Evans procedure can be used in patients with the same indications as the hamstring reconstruction. In this procedure, the peroneal brevis is split using one third of it through a drill hole in the tip of the fibula, exiting the posterior fibula. The peroneal tendon is then secured with an interference screw and the Broström is placed over it. Results with the Broström-Evans procedure have also been good.22

Challenges

Despite having a stable ankle postoperatively, some patients still complain of pain, aching, swelling, and crepitation.26 Many of these complaints may be related to preexisting intraarticular pathology such as degenerative joint disease, osteochondral lesions of the talus, loose bodies, chronic synovitis, and chronic scarring. Occasionally the ankle can be made too tight at the time of reconstruction; this severely limits the patient’s ability to invert. This is the single most serious complication after ankle reconstruction. If a patient does not have full motion after surgery, especially full inversion and eversion, rehabilitation is significantly compromised and the patient tends to develop a painful valgus hindfoot.

Precautions and Contraindications

The physical therapist should increase the level of rehabilitation gradually for the patient after surgery. Too-vigorous exercise and the use of isokinetic machines can lead to increased pain, shear stress, and swelling that can last for weeks to months and stretch the reconstruction. If this occurs, the ultimate results can be compromised and the patient, physician, and physical therapist can all become quite frustrated. Every patient progresses at a different rate and the exercise program should be customized to the individual needs of each patient.

Rehabilitation Concerns

The therapist should contact the physician whenever pain appears to be out of proportion to expectations. In addition, any wound drainage, evidence of fever or infection, and increased laxity should alert the therapist to interact with the surgeon. If the patient has an acute episode of pain or feels a “pop” or significant change during rehabilitation or ADLs, the surgeon should be alerted immediately.

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

The first 6 weeks after surgery are important for the succes of the surgery. Whether the reconstruction was done with primary ligamentous repair (as in the Broström procedure), with tendon augmentation (as in the Chrisman-Snook procedure), or with hamstring reconstruction, the initial tissue healing stage is important.9,31 The surgical reconstruction to correct the ligamentous instability is only as good as the stability gained from soft tissue healing. Soft tissue healing is considered the maximal protection stage.

Evaluation

The initial postoperative evaluation gives the therapist a baseline from which to proceed in returning the patient to desired independent function. Initial ROM measurements are taken both for active range of motion (AROM) and passive range of motion (PROM). PROM is measured within a pain-free range, especially while measuring forefoot inversion.

![]() The physical therapist has a responsibility to the surgeon and the patient to protect the lateral ligamentous reconstruction. Forefoot inversion stresses the reconstructed tissues and must be carefully engaged. Manual muscle testing to determine strength of the lower extremity can be part of the initial evaluation. However, muscle testing at the ankle is delayed until the patient has progressed and accommodated to resisted exercises at the ankle.

The physical therapist has a responsibility to the surgeon and the patient to protect the lateral ligamentous reconstruction. Forefoot inversion stresses the reconstructed tissues and must be carefully engaged. Manual muscle testing to determine strength of the lower extremity can be part of the initial evaluation. However, muscle testing at the ankle is delayed until the patient has progressed and accommodated to resisted exercises at the ankle. ![]() The therapist should avoid having the patient perform a single–leg heel raise, which is usually advocated to determine normal gastrocnemius-soleus strength, because of decreased proprioception and the significant muscle deficits resulting from the effects of immobilization. The incision is assessed for mobility and hypersensitivity after complete healing has occurred. Operative damage to the sural nerve and the lateral branch of the superficial peroneal nerve has been reported as a cause of decreased sensation in the involved ankle.10,37 Joint effusion and soft tissue edema can be factors in limited ROM, proprioception deficits, and the inability to strengthen the joint. Joint and soft tissue mobility also are assessed at the limits of ROM.

The therapist should avoid having the patient perform a single–leg heel raise, which is usually advocated to determine normal gastrocnemius-soleus strength, because of decreased proprioception and the significant muscle deficits resulting from the effects of immobilization. The incision is assessed for mobility and hypersensitivity after complete healing has occurred. Operative damage to the sural nerve and the lateral branch of the superficial peroneal nerve has been reported as a cause of decreased sensation in the involved ankle.10,37 Joint effusion and soft tissue edema can be factors in limited ROM, proprioception deficits, and the inability to strengthen the joint. Joint and soft tissue mobility also are assessed at the limits of ROM.

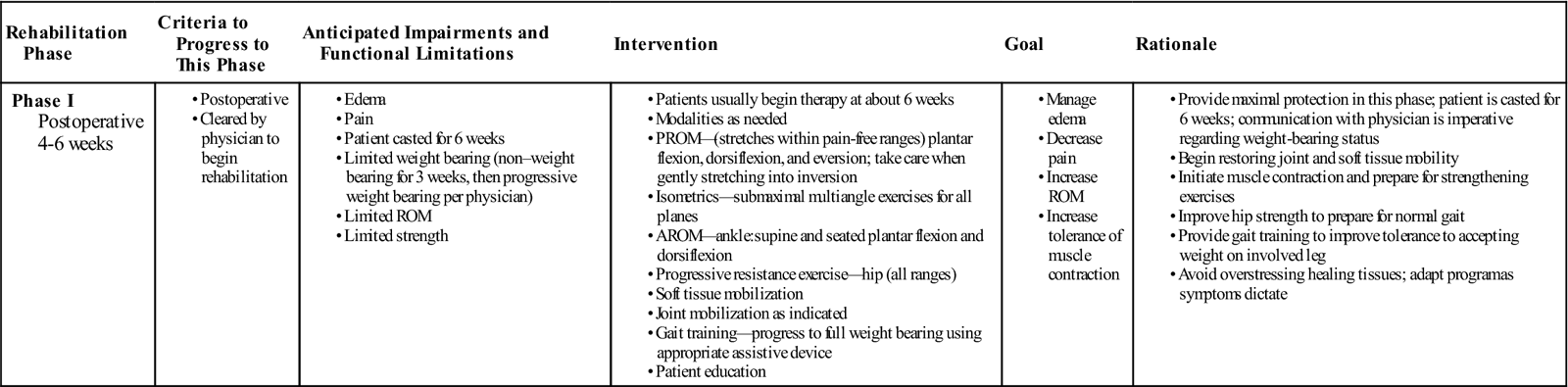

Phase I

TIME: Weeks 4 to 6 after surgery

GOALS: Decrease pain and swelling, restore joint and soft tissue mobility, increase strength in lower extremity and ankle, increase proprioception, normalize gait, maintain cardiovascular fitness, and provide patient education (Table 28-1)

TABLE 28-1

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase I Postoperative 4-6 weeks |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

AROM, Active range of motion; PROM, passive range of motion; ROM, range of motion.

During this maximal protection phase the patient is casted and allowed to progress from non–weight bearing to weight bearing. The patient remains non–weight bearing and the cast is removed at the first postoperative visit for wound inspection. A second cast is applied for an additional week and the stitches are removed. Weight bearing is initiated during the third week and the cast is removed at the sixth week. At this point the patient is placed in a controlled action motion (CAM) walker brace and compression stocking or in a small brace, depending on the individual patient. At 6 weeks the patient is started on ROM and strengthening exercises in physical therapy, as well as pool exercises. Some authors have advocated a limited ROM of 10° dorsiflexion and 10° of plantar flexion, with partial weight bearing from 2 to 6 weeks after surgery.30 Formal physical therapy is usually initiated at 6 weeks when the cast is removed. At this time the tissues should be adequately healed and ready to tolerate stresses within a pain-free ROM. Studies have shown that motion is beneficial to nourish cartilage, prevent soft tissue contractures, and restore joint mobility.37After performing the initial evaluation, the physical therapist can implement appropriate treatment. Initially, the therapist performs grades I and II joint mobilization along with PROM, especially inversion, within pain-free ranges. At 6 weeks after surgery the ligaments should have healed sufficiently to allow gentle active movement.38

![]() However, at this stage the soft tissue is unable to withstand significant forces into inversion.4 The patient is able to perform AROM for plantar flexion and dorsiflexion using pain as a guide; submaximal multiangle isometrics for all planes also are used at this stage of the rehabilitation. Soft tissue and joint mobilizations are started to reverse the effects of immobilization and surgical trauma. Effusion, pain, and soft tissue edema are treated with the appropriate modalities. Research has suggested that ice independently is not effective in reducing postoperative edema. Instead, studies have reported an increased effectiveness of reducing postoperative edema using cold compression therapy.39–41 Efforts to normalize full weight-bearing gait without assistive devices should include gait training drills. Proper foot mechanics throughout the stance phase of gait can be emphasized if pain is minimal or absent. A home exercise program emphasizing increased frequency and decreased intensity of exercises should be initiated at this time. The therapist should clearly instruct the patient on precautions to protect healing tissues. The program may be altered as needed by the therapist.

However, at this stage the soft tissue is unable to withstand significant forces into inversion.4 The patient is able to perform AROM for plantar flexion and dorsiflexion using pain as a guide; submaximal multiangle isometrics for all planes also are used at this stage of the rehabilitation. Soft tissue and joint mobilizations are started to reverse the effects of immobilization and surgical trauma. Effusion, pain, and soft tissue edema are treated with the appropriate modalities. Research has suggested that ice independently is not effective in reducing postoperative edema. Instead, studies have reported an increased effectiveness of reducing postoperative edema using cold compression therapy.39–41 Efforts to normalize full weight-bearing gait without assistive devices should include gait training drills. Proper foot mechanics throughout the stance phase of gait can be emphasized if pain is minimal or absent. A home exercise program emphasizing increased frequency and decreased intensity of exercises should be initiated at this time. The therapist should clearly instruct the patient on precautions to protect healing tissues. The program may be altered as needed by the therapist.

Precautions

The therapist should take a few precautions during this phase.

![]() Careful monitoring of exercise progression and intensity of the workout session is crucial to avoid overstressing healing tissues. The therapist must caution the patient to avoid aggressive stretching and strengthening of lateral ankle tissues early in the rehabilitation program; progress should be cautious and slow. Exercises that cause increased symptoms in the lateral ankle complex must be modified or avoided.

Careful monitoring of exercise progression and intensity of the workout session is crucial to avoid overstressing healing tissues. The therapist must caution the patient to avoid aggressive stretching and strengthening of lateral ankle tissues early in the rehabilitation program; progress should be cautious and slow. Exercises that cause increased symptoms in the lateral ankle complex must be modified or avoided.

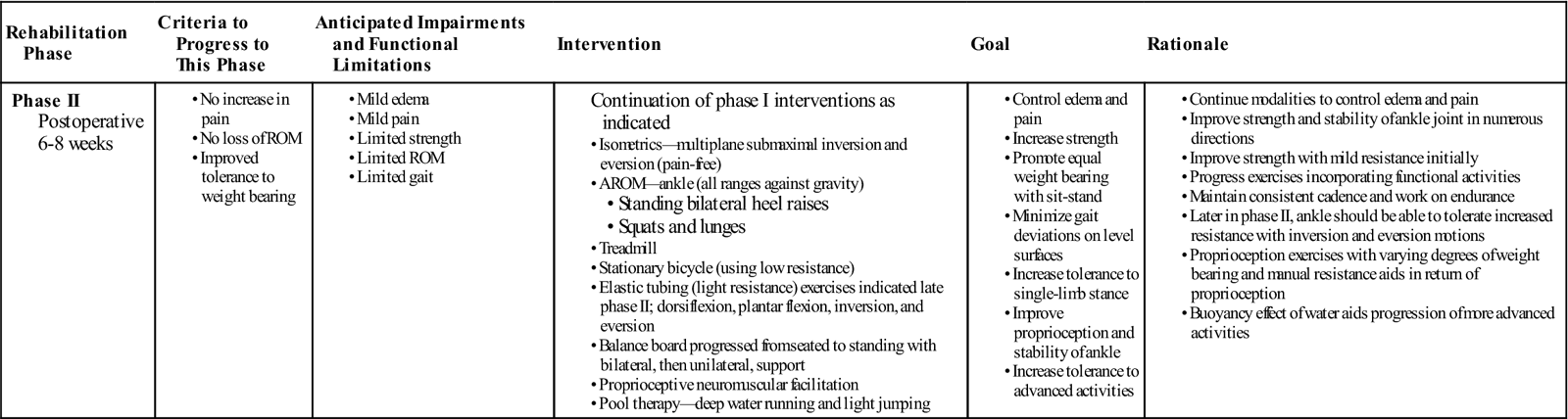

Phase II

TIME: Weeks 6 to 8 after surgery

GOALS: Return gait within normal range, maintain normal ROM, increase strength, control pain and swelling, increase proprioception (Table 28-2)

TABLE 28-2

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase II Postoperative 6-8 weeks |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

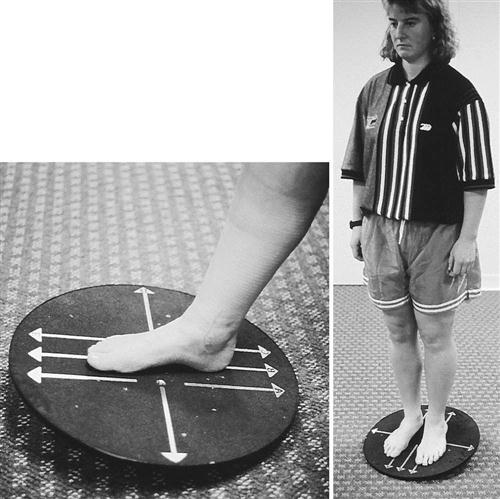

Phase II is overlapped with phase I as the patient’s ROM begins to progress and therapeutic exercise options are expanded. At this stage rehabilitation is similar to that advocated in the literature for lateral ankle sprains.11 Multiplane isometrics and AROM against gravity progress to exercises with appropriate grades of submaximal resistance using weights or rubber tubing. Peroneal strengthening is a major focus because repeated trauma resulting from the instability may lead to weakness of these muscles.4 Activities to increase strength may occur on land or in a pool. On land, early proprioceptive activity is initiated with the use of a balance board as a means of increasing functional stability.42,43 The patient progresses from sitting to standing, with bilateral and then unilateral support. One-leg standing also is initiated. Bilateral heel raises are started and progressed to unilateral as tolerated by the patient and according to the therapist’s discretion. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) is an excellent strengthening tool for the lower kinetic chain. In the pool, activities may include light jogging and jumping exercises in shallow water. Lunges and squats also are effective. The patient should continue with deep water running exercises for increased cardiovascular fitness. Gait training is an important aspect of the rehabilitation program and should be given priority. An aberrant pattern reinforces itself and leads to continued limitations in ROM and strength. Walking on a treadmill at a moderate speed with a low-to-moderate grade as tolerated aids in gait training.

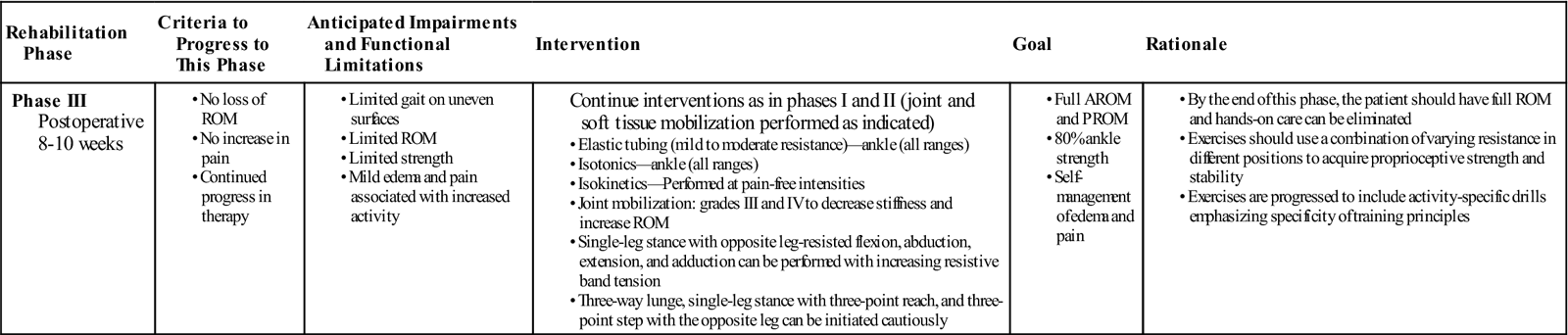

Phase III

TIME: Weeks 8 to 10 after surgery

GOALS: Focus on training to allow return to work and sports, continue ankle mobilization and passive stretching, prevent pain and swelling (Table 28-3)

TABLE 28-3

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase III Postoperative 8-10 weeks |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

AROM, Active range of motion; PROM, passive range of motion; ROM, range of motion.

When ROM and gait are within normal limits, isokinetic strengthening for inversion and eversion can be initiated. At this time the patient should be able to tolerate a submaximal strengthening program without exacerbation of symptoms. Resistive exercises for plantar flexion and dorsiflexion are initiated at 8 weeks. Inversion and eversion resistive exercises must be performed to the tolerance of the patient. Single-leg stance with opposite leg-resisted flexion, abduction, extension, and adduction can be performed with increasing resistive band tension. Patients may begin performing exercises on partial–weight bearing equipment such as the Shuttle MVP, including single/double leg press and toe raises. All resistive exercises should be performed without pain. Three-way lunge, single-leg stance with three-point reach and three-point step with the opposite leg can be initiated cautiously. The ability to perform pain-free weight training and isokinetic training is a good indication that soft tissue strength is progressing well.

![]() The therapist must monitor the progression of resistive exercises to ensure that symptoms are not exacerbated. The patient may be ready for discharge after phase III or may progress to phase IV depending on the prior level of fitness or activity and goals.

The therapist must monitor the progression of resistive exercises to ensure that symptoms are not exacerbated. The patient may be ready for discharge after phase III or may progress to phase IV depending on the prior level of fitness or activity and goals.

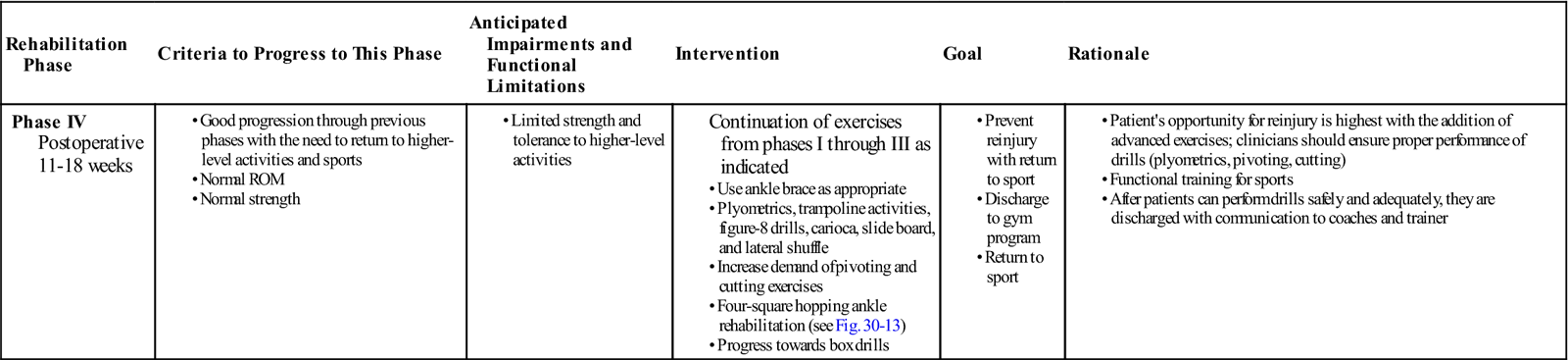

Phase IV

TIME: Weeks 11 to 18 after surgery

GOAL: Return to sporting activities (Table 28-4)

TABLE 28-4

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase IV Postoperative 11-18 weeks |

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

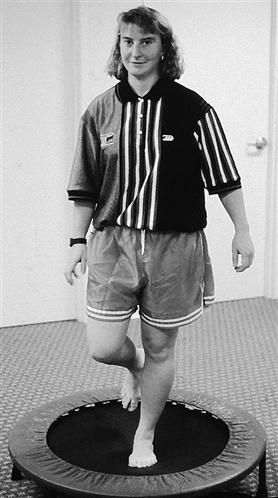

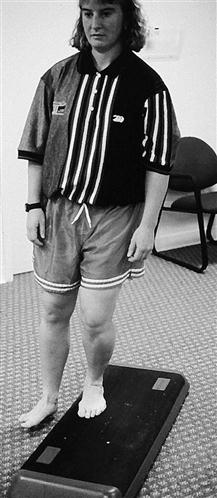

The goal of rehabilitation is, in general, for the patient to return to sporting activity 11 to 18 weeks after surgery; an ankle brace is used initially on return to sporting activities.10,31 Exercise should continue with the therapist monitoring patient progress. Exercises in this phase are more advanced, and chances of reinjury are greater. In this final phase of rehabilitation the patient should be able to perform all exercises safely and correctly, with proper form and technique and with little verbal cueing from the therapist. After the AROM and PROM are within normal limits and strength has returned to normal, sport-specific and functional training can be implemented. Exercise options include plyometrics, trampoline activities, box drills, figure-8 drills, carioca, slide board, and lateral shuffles (Figs. 28-12 through 28-15). Many of the initial ankle injuries resulted from sporting activities such as cutting activities and movements requiring quick reflexes and balance. Although not in the scope of this chapter, retraining the vestibular system is also an important part of an athlete returning to their sport of choice. Incorporating vestibular exercises with sport-specific movements and exercises can help the athlete achieve his or her goals (Fig 28-16). These activities should be incorporated into the rehabilitation program.

Suggested Home Maintenance for the Postsurgical Patient

An exercise program has been outlined at the various phases. The home maintenance box outlines rehabilitation suggestions the patient may follow. The physical therapist can use it in customizing a patient-specific program.

Troubleshooting

Limited dorsiflexion can be a problem with most patients because of limited talar tibia-fibula mobility as a result of joint restrictions and soft tissue tightness. If restrictions exist at the talocrural joint, long-axis distraction thrust techniques are useful. In addition, mobilization of the talus, tibia, and fibula can be useful. Anterior and posterior glides to these bones help restore dorsiflexion. The gastrocnemius and soleus muscle group can be the major limiting factor in dorsiflexion ROM. Low-load prolonged stretching techniques in combination with heat can be beneficial in increasing soft tissue extensibility.44 The load of the stretch is to the patient’s tolerance for 20 to 30 minutes, one or two times per day.

Another method to prevent chronic ankle sprains is to use biomechanical foot orthotics. In theory, biomechanical foot orthotics are designed to enhance joint position, increasing the shock-absorbing capabilities of the lower limb and improving muscle function.

Summary

A successful outcome for lateral ligamentous reconstruction includes no recurrent instability, normal ROM and strength, and no pain with weight-bearing activities. A successful functional outcome is achieved if the patient experiences no instability on returning to daily activities or sporting activities. The first step toward a good outcome is adequate postoperative stabilization. However, the success of the surgical procedure depends on postoperative rehabilitation in which the patient, surgeon, and therapist work closely to achieve a functional ankle.

Clinical Case Review

1Will, who is 18 years old, tore his ATF ligament while playing basketball. The tear occurred over a 1-year period after accumulating multiple ankle sprains. He had an ATF ligament repair 8 weeks ago. Since then his physical therapy has consisted of massage, ultrasound, AROM and PROM exercises, cryotherapy with compression, and a home exercise program. His main complaint is stiffness during gait, while ascending stairs, and during attempts to squat partially. Dorsiflexion is limited by 10° with moderate edema noted. What treatment is most likely to improve Will’s dorsiflexion ROM and decrease edema?

The patient was reassessed for associated restrictions. A mobilization technique was performed at the proximal and distal fibula. An AP movement was applied to the proximal fibular head, and a posteroanterior (PA) movement was applied to the lateral malleolus to increase dorsiflexion. This was followed by stretching and ROM exercises to reinforce dorsiflexion. Will’s dorsiflexion PROM increased to 18°. Pain with gait, stairs, and squatting was dramatically decreased after the first treatment.

2Leigh is a 30-year-old woman who tore her left ATF ligament while performing step aerobics. She had an ATF ligament repair 10 weeks ago. She has complained of knee and back pain on the unilateral side. She has asymmetric pelvic imbalance, with left iliac crest higher than the right and the left anterosuperior iliac spine (ASIS)/posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) higher than the right. Decreased knee extension left versus right. Progress with exercises has decreased because of pain during many of the closed-chain exercises such as single-leg stance, double-heel lifts, minisquats, and walking more than 8 minutes on the treadmill. What types of activities can be performed for her unilateral imbalances while increasing core stability?

The therapist explained to Leigh that any activities causing her to substitute secondary to increased pain must be modified. The patient was reassessed, and associated restrictions at the pelvis were recorded. A long axis distraction was performed to correct pelvic asymmetry. Appropriate hamstring stretches were performed to increase muscle length. As exercises were modified and asymmetries were corrected, Leigh was able to perform the following closed-chain exercises: forward lunges, backward lunges, lateral lunges, heel raises with minisquat, and single-heel raises performed on a leg press machine using 70 lb. She was also able to perform backward walking, minimal walking on a treadmill, and jogging or running in the pool. As strength and tolerance to exercise increased, Leigh progressed to more challenging exercises, which included core stabilization activities.

3Karen is 22 years old and plays basketball primarily on the weekends. She tore her ATF during a pick-up game when she stepped abnormally causing her ankle to turn into extreme inversion. She had an ATF ligament repair 11 weeks ago. Progress with exercise has decreased because of pain during many closed-chain activities. What factors could be involved that would cause pain during these activities?

During an additional assessment, it was found that Karen had restrictions with AP proximal fibular glides and PA distal fibular glides. Calcaneal eversion was also limited. Graded mobilizations were performed at the proximal and distal fibular heads, which released the calcaneal eversion and decreased the patient’s pain during activity.

4Jason is a 30-year-old man who suffered an ATF tear after slipping on wet grass while performing yard work. He had an ATF ligament repair 12 weeks ago. He reports that his ankle pain has started to decrease but that he is noticing progressively increased pain at the third through fifth distal metatarsal heads. The pain is progressing to affect gait. What should the therapist assess?

The therapist, when learning of this clinical change, assessed the foot position and compared findings bilaterally. The patient was found to have increased rear foot pronation and forefoot supination on the affected side as compared with the unaffected side. The therapist attempted a temporary orthotic trial and posted the patient using a 3° medial rear foot wedge and a 3° lateral forefoot wedge on the affected extremity. At the next session, the patient reported decreased ankle and distal metatarsal pain on the affected side. The patient would later be fitted for permanent orthotics.

5Jim is 17 years old and tore his ATF while rounding second base during a high school baseball game. He had an ATF ligament repair 16 weeks ago. He has progressed well through rehabilitation but was having difficulty initiating higher-level activities. How did the therapist progress this athlete for him to return to baseball for the next season?

The therapist initiated activities that were sports specific to increase functional stability. The patient performed multidirectional single-leg hopping, including forward, backward, and side to side. The patient began box exercises, including shuffle sprint and box X with pivot. He was progressed in proprioceptive activities, including unilateral leg stand with opposite LE resistive-band flexion, extension, and abduction, and biomechanical ankle platform system (BAPS) board activities. The exercises were progressed, increasing the time from 1 to 2 minutes.

6Steve is an 18-year-old senior track athlete being actively recruited by several Division I universities for pole vaulting. During a track meet, the patient performed his vault and, upon landing, severely inverted his right ankle. He entered the clinic with severe bruising around the ankle with +2 pitting edema. He was tender over the lateral malleoli and peroneals, as well as the lateral ligaments. He has no significant gait deviations and has reported that he has been jogging. What is the differential diagnosis and course of treatment?

The therapist first instructed Steve to cease jogging activities immediately and used the tuning fork and tapping method to rule out possible fracture, which was negative. Radiographs later showed no fracture present. The patient was positive with talar tilt, anterior drawer, and high ankle sprain. The patient demonstrated MMT within normal limits for all ankle motions except ankle eversion, which showed pain and weakness at 3+/5. Grossly, the patient had full ROM with pain at end range. The course of treatment included initial edema reduction and pain management while maintaining full ROM. Because of peroneal involvement, the therapist was able to begin strengthening in all planes except eversion, which was limited to isometrics. The patient later performed proprioception and plyometric exercises and returned to pole-vaulting after 8 weeks, with an ankle-stabilizing orthosis (ASO) ankle brace.

7Elizabeth is a 15-year-old competitive gymnast with a history of chronic ankle sprains to her right ankle during her gymnastics competitions. The most frequent occurrence of her injury involves the vault and tumbling with floor exercises. She has not undergone any surgical intervention but wishes to continue competing in her sport. What type of treatment plan should the therapist initiate to allow Elizabeth to return to her sport?

Upon evaluation, the therapist finds that she has the following objective findings: Restricted passive dorsiflexion/talar gliding, weakness with MMT to the peroneals, tenderness to palpation along the ATF ligament/sinus tarsi and also tenderness in her Achilles tendon, she was also noted to have significant propriocpetive deficits, and posterior hip strength deficits as well. Treatment began with modalities to decrease pain/inflammation and to help start scar tissue remodeling including: infrared light, ultrasound, crossfriction massage and soft tissue mobilization of the gastroc/soleus and Achilles tendon. The restricted dorsiflexion was addressed with long-axis distraction to the talocrural joint. She was put on a progressive strengthening program for her posterior hip muscle deficits, as well as an eccentric training regimen for her Achilles tendon. She was also performing progressive inversion/eversion strengthening with thera-band and PNF diagonal strengthening with the therapist providing manual resistance. She then progressed to plyometric training first with partial–weight bearing equipment, such as the Shuttle MVP, and then to more aggressive plyometric training on devices such as the Vertimax with an emphasis on her landing mechanics. The patient was also placed on a progressive perturbation training program to address her proprioceptive deficits. Elizabeth was also advised to either tape her ankle or obtain a brace for her to use during competitions.

8Elaine is 45-year-old female who injured her right ankle in an MVA while on vacation. Once she returned home, she was found to have torn her ATF ligament and underwent the Broström-Gould procedure to reconstruct the ligament. Upon coming to physical therapy 6 weeks following the procedure, Elaine is ambulating with crutches and a CAM boot. She reports pain over the lateral malleoli, ATFL, sinus tarsi, and lateral syndesmosis. She also has impaired sensation and increased scar tissue surrounding the incision. Atrophy and limited soft tissue mobility of the gastros/soleus comlex are noted as well. How would the therapist initiate treatment at her current level?

The patient was instructed in a HEP consisting of towel gastrocnemius/soleus stretching, desensitization and scar mobility exercises, submaximal and pain-free isometrics for inversion/eversion, and AROM exercise for plantar and dorsiflexion. While in the clinic; high-voltage electrical stimulation was used to address muscular atrophy of the gastrosnemius/soleus complex and cryotherapy with interferential electrical stimulation was used if there was pain following treatments. The patient began a progressive gait training program under the supervision of the therapist which began on two crutches, next to one crutch on the contralateral side, then a single-point cane and finally no assistive device. The final stage was allowed once the patient was able to ambulate with proper mechanics and a nonantalgic gait pattern.

9Brandon is a 16-year-old male basketball player who has had recurrent ankle sprains. At the end of the season, he again sprained his ankle by landing on an opposing players’ foot and severely inverting his foot while running. Brandon and his parents are concerned about the new injury/possible fracture and want to address the continued recurrent instability in his ankle that has occurred over the last year. What should the therapist do to address these issues?

To rule out the possible fracture the therapist can use the Ottawa ankle rules for fracture. The therapist can also use the tuning fork technique or attempt ultrasound over the painful area. If there is a fracture, ultrasound over the area will usually reproduce the patient’s pain and indicate possible bony pathology. The therapist should arrange or contact the patient’s orthopedic doctor and relay these concerns so that the surgeon can give the patient and family all of the possible treatment options and initiate diagnostic imaging if warranted. The therapist can also educate the patient and his family on the problems associated with recurrent ankle instability; such as early joint degeneration, impaired balance/proprioception, and decreased function with higher level activities (i.e., running, jumping, cutting sports).

10Ryan is a 25-year-old who injured his ankle after falling off of his bicycle. He was taken to the emergency room and was stabilized. After the initial swelling had decreased Ryan underwent surgical reconstruction of his ATF ligament with arthroscopy to his talocrural joint. Ryan was a previous patient who the therapist had treated for other injuries over the past year. The day after the surgery, Ryan calls the therapist because he is concerned about his increase in pain/swelling following the procedure. He also reports numbness/tingling in his foot and tenderness in his calf. What should the therapist do?

Without the patient being seen in the clinic, assessment is limited. But the therapist should tell Ryan to follow-up with his surgeon immediately to rule out any possible compartment syndrome or deep vein thrombosis which may have occurred as a result of the procedure. If the therapist is familiar with the surgeon, he or she should then also call the surgeon to relay these symptoms and concerns to the physician so that he or she can appropriately address these issues.

11Cliff is a 26-year-old Air Force officer who injured his ankle while doing his routine physical training regimen. While running he stepped off the side of the track and experienced a plantar flexion with inversion injury to his ankle. He then underwent surgical reconstruction and is currently 4 months postop and would like to begin running again. How should the therapist assist Cliff to return to running without exacerbating his pain?

Before beginning a running program, Cliff must demonstrate certain objective findings before attempting to begin the program. He should demonstrate no restrictions in ankle mobility specifically dorsiflexion, be able to perform three sets of 15 repetitions of single–leg calf raises without ankle pain, demonstrate near symmetric single-leg balance, and appropriate strength in the other lower extremity muscle groups (i.e., hip, quadriceps, and hamstring strength) involved with running. A nice precursor to running can be the elliptical machine, or running in deep water (no impact), or on an underwater treadmill at a certain percentage of his body weight. If Cliff has had no adverse reactions to the above precursors he can start with a progressive treadmill running program. He may begin with a light warm-up at a nice cadence for 3 to 5 minutes and then begin with an interval program at a pace that simulates a light jog for him. Intervals should start with 1 minute of jogging, followed by a minute of walking at a fast pace; then 2 minutes of jogging with 1 minute of walking and then 3 minutes of jogging; again followed by a walking/cool down period. He should remain with this intensity of training for at least a week to see how he is responding. If he is responding well he may begin to increase both the speed and duration of his jogging/running bouts over the ensuing weeks.

12Ashley is a 17-year-old tennis player who has had recurrent ankle sprains to her left ankle over the past 2 years. She has increased inversion with the talar tilt test compared with her right ankle. She does not report any recurrent instability with normal daily activities, only with her athletic activities. She does not wish to undergo surgery and would like a conservative approach to address her ankle issues. What should the therapist do?

The therapist should do a full lower extremity evaluation examining lower extremity muscle strength, ROM, joint mobility/gliding, balance/vestibular testing, and foot/ankle mechanics for possible orthotic intervention. Deficits were found in Ashley’s posterior hip musculature and ankle eversion strength. She was found to have proprioceptive deficits on the left with balance testing. Observation of her static and dynamic mechanics revealed increased femoral Q angle contributing to increased knee valgus with dynamic movements, she also demonstrated increased foot pronation with collapse of the midtarsals during the stance phase of gait. So to address these deficits, Ashley should be put on a progressive strengthening program for her posterior hip muscles and peroneals. She should also be fitted for orthotics to address her foot/ankle mechanics. A progressive balance and proprioceptive training program should also be initiated. While undergoing this treatment program, Ashley will need to reduce her tennis training, and it was recommended that she tape or brace her ankle in some fashion until her strength and mechanical issues were resolved.

13Describe a progressive training program for the peroneals.

Initially after injury or surgery, the patient may begin with submaximal isometrics. Progression with isometrics can increase with the amount of force or with the duration of holding the isometric contraction. The next phase would be pain-free active range motions. The patient may begin first while sitting or lying and then to progress to a sidelying position so that the ankle is everting against gravity. Following this stage, he or she may progress to elastic tubing/Theraband exercises. Focus should also be placed on the eccentric component of these exercises which will assist with tendon strengthening. The therapist may also do PNF diagonals with manual resistance at this stage. Once he or she has completed these phases of the program, which were designed to isolate the peroneals, the focus of the program should shift to more whole body and sport-specifc movements, with emphasis on lateral and diagonal movement patterns.