CHAPTER 3 Lateral Epicondylitis: Débridement, Repair, and Associated Pathology

Lateral humeral epicondylitis was first described in the German literature by Runge in 1873.1 Ten years later, Morris reported an association between lateral epicondylitis and lawn tennis, leading to its common designation as tennis elbow.2 Since these original descriptions were published, multiple causes and various treatments for this condition have been proposed.

Despite advances in our understanding of the pathoanatomy of lateral epicondylitis, controversy remains regarding its optimal nonoperative and operative management. Most patients respond successfully to a variety of conservative methods. In the studies reported by Boyd and McLeod,3 Coonrad and Hooper,4 and Nirschl and Pettrone,5 4% to 11% of patients ultimately required operative intervention for recalcitrant symptoms. Many different operative procedures have been described in the orthopedic literature: percutaneous,6–11 endoscopic,12,13 and myriad open techniques, such as excision of abnormal degenerative tissue with simple suture repair4,5,7,10,14-17 or formal repair of the extensor tendons back to the lateral epicondyle.18–20 Clinical outcomes of arthroscopic treatment have been reported.10,16,21–29 In one study, we found high rates of clinical success for our patients with lateral epicondylitis treated arthroscopically using the technique described in this chapter.21,22

ANATOMY

Nirschl and associates detailed the most commonly accepted theory of the pathogenesis of lateral epicondylitis.5,30 Building on the previous findings of Cyriax,31 Goldie,32 and Coonrad and Hooper,4 Nirschl observed that the basic underlying lesion was in the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) tendon. Repetitive overuse leads to microtears in the ECRB origin. Tendinous nonrepair and replacement with immature reparative tissue often follow. Histopathologic examination revealed an absence of inflammatory cells and the presence of a degenerative process, with tissue first characterized as angiofibroblastic hyperplasia and later modified to angiofibroblastic tendinosis.5,30,33,34

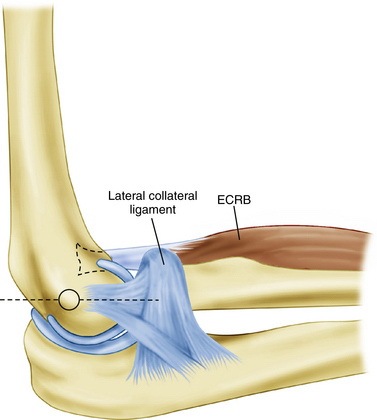

In a cadaveric study, Cohen and associates35 characterized the ECRB origin as diamond shaped and as beginning just anterior to the most distal aspect of the lateral supracondylar ridge. The anatomic ECRB footprint is located between the most proximal aspect of the capitellum and the midline of the radiocapitellar joint (Fig. 3-1). The lateral collateral ligamentous complex, consisting of the radial collateral ligament, annular ligament, accessory collateral ligament, and lateral ulnar collateral ligament, lies posterior to the ECRB origin. This lateral collateral ligamentous complex is not disrupted during arthroscopy as long as resection of the ECRB and elbow capsule is kept anterior to a line bisecting the radial head.36

PATIENT EVALUATION

Diagnostic Imaging

Lateral epicondylitis is a clinical diagnosis. We routinely obtain plain anteroposterior, lateral, and axial radiographic views of the elbow as part of the initial evaluation in the patient presenting with elbow pain. Although they are frequently normal, the radiographs may show radiocapitellar arthrosis, which should be included in the differential diagnosis. Plain radiographs may show soft tissue calcification adjacent to the lateral epicondyle in approximately 25% of patients, especially if the patient previously had steroid injections. Although unnecessary for the diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide additional information regarding suspected intra-articular pathology, the integrity of the lateral collateral ligamentous complex, and the presence and extent of extensor tendon tearing.37

TREATMENT

Conservative Management

Many nonoperative treatments have been reported. A regimen that includes activity modification, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, counterforce bracing, and corticosteroid injections is usually successful in reducing symptoms and allowing a progressive return to unrestricted activities. Novel approaches include injections of buffered platelet-rich plasma38 or botulinum toxin39 and application of extracorporeal shock wave therapy.40

Arthroscopic Technique

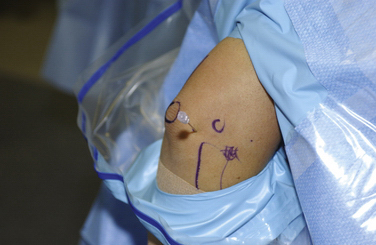

For the arthroscopic procedure, the patient can be placed in the supine, lateral decubitus, or prone position. We prefer the prone position with the use of a general anesthesia to allow accurate postoperative neurovascular assessment. A well-padded tourniquet is applied to the upper arm, which is then placed into a commercially available arm holder (Fig. 3-2). The extremity is then prepared and draped in standard fashion. A compressive dressing is wrapped around the forearm to help prevent leakage of fluid into the distal soft tissues. Several bony anatomic landmarks and important structures are outlined with a marking pen to assist in proper portal creation: medial and lateral epicondyles, radial head, olecranon tip, and ulnar nerve (Fig. 3-3).

The limb is exsanguinated, and the tourniquet is inflated to 250 mm Hg. An 18-gauge spinal needle is introduced into the lateral soft spot, which can be found in the center of a triangle formed by the palpable radial head, lateral epicondyle, and olecranon. The joint is injected with approximately 20 to 30 mL of saline (Fig. 3-4). Joint distention pushes the neurovascular structures more anterior, thereby protecting them from iatrogenic injury.

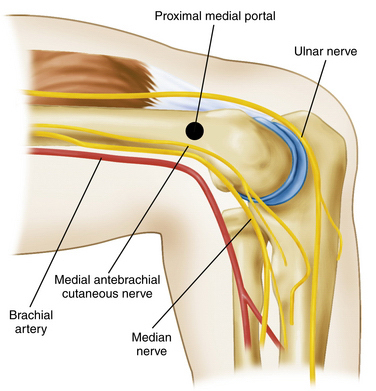

The proximal medial portal is created approximately 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and 1 cm anterior to the medial intermuscular septum (Fig. 3-5). To protect against injury to the sensory nerves, we use a nick and spread technique, in which only the skin is incised, and a hemostat is used to spread the subcutaneous tissues. Stothers and colleagues41 found the proximal medial portal to be, on average, 2.3 mm away from the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, 7.6 mm away from the median nerve, and 18 mm away from the brachial artery with the elbow in flexion. The ulnar nerve is typically located 12 mm from this portal and lies anterior to and is protected by the medial intermuscular septum.

A blunt trocar is inserted through the portal. The surgeon should aim toward the center of the joint and maintain contact with the anterior surface of the humerus. Backflow of fluid through the cannula confirms entry into the joint (Fig. 3-6).

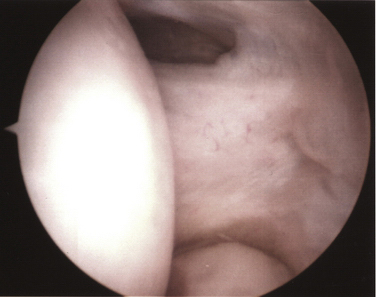

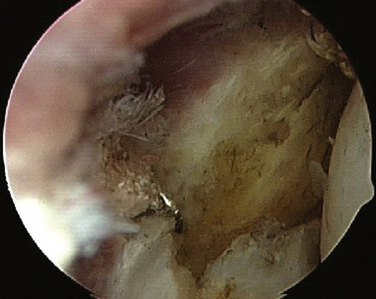

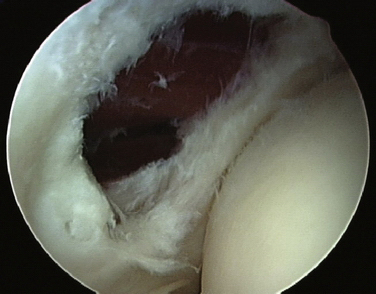

The 4-mm, 30-degree arthroscope is inserted into the joint. The lateral capsule and radiocapitellar articulation are easily inspected. According to Baker’s classification system,21 the condition of the capsule is classified as type 1 (i.e., intact capsule), type 2 (i.e., linear capsular tears), or type 3 (i.e., capsular rupture) (Fig. 3-7). Irregular extension of the annular ligament overlying the radial head, or synovial fringe, can be appreciated in some cases. We believe that this structure can be a source of lateral elbow symptoms that often mimic lateral epicondylitis and that it should be removed concomitant with the ECRB resection.26

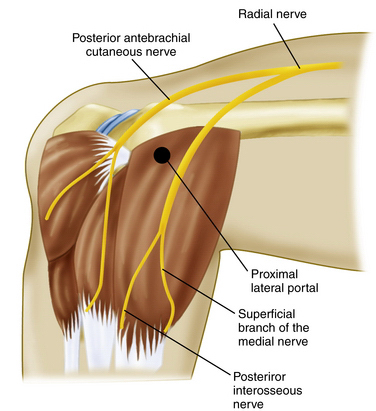

The proximal lateral portal is typically located 1 to 2 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle along the anterior humeral surface (Fig. 3-8). This portal is established after needle localization using an outside-in technique (Fig. 3-9). Stothers and coworkers41 found the radial nerve to be 9.9 mm away from this portal and the posterior branch of the antebrachial cutaneous nerve to be an average of 6.6 mm away from the portal with the elbow flexed.

FIGURE 3-9 The proximal lateral portal is created with an outside-in technique for correct portal localization.

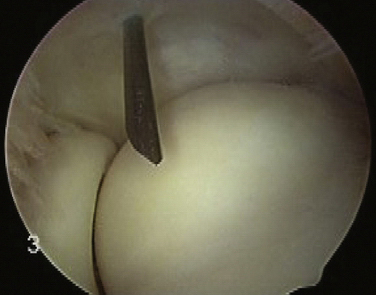

A blunt trocar is used to enter the joint, followed by a small, motorized shaver. A portion of the lateral capsule is resected to reveal the underlying common extensor origin (Fig. 3-10). The ECRB tendon lies between the common extensor origin and the removed capsule. The shaver is exchanged for a monopolar radiofrequency device (Fig. 3-11) The ECRB origin is then completely released from its insertion and the tendinosis tissue ablated (Fig. 3-12). To protect the lateral ligamentous structures, care is taken not to extend the release posterior to a line bisecting the radial head. Early in our experience, we decorticated the lateral epicondyle; however, several patients developed postoperative bony tenderness that was not present preoperatively. We no longer routinely decorticate the lateral epicondyle.

FIGURE 3-10 A portion of the lateral capsule is removed to reveal the underlying extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon.

If the patient had preoperative concurrent posterior or posterolateral pain on terminal elbow extension, we inspect the posterior compartment through the posterior and direct lateral portals. If no such symptoms were present at the preoperative evaluation, we do not routinely examine the posterior compartment. The portal sites are closed with simple nylon sutures, and a sterile dressing is applied.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

PITFALLS

Postoperative Rehabilitation

The first postoperative visit is scheduled within 7 days of surgery. Sutures are removed at that time. If potential motion loss is a concern or the patient has difficulty regaining full extension, formal physical therapy is prescribed. Home exercises, including simple stretching and strengthening, are initiated as the patient’s symptoms allow. Patients typically return to light activities at 2 weeks after surgery and to sports at approximately 6 weeks postoperatively.

OUTCOMES

We reviewed the long-term outcomes of our initial series of patients who were treated with arthroscopic resection of the ECRB origin for recalcitrant lateral epicondylitis.22 Thirty elbows in 30 patients were evaluated at a mean follow-up of 130 months. Patients were asked to rate their level of pain using a numeric scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain). They were also asked to rate their elbows according to the 12-point functional portion of the Mayo Clinic Elbow Performance Index.

The high rate of success in Baker’s initial series of patients was maintained at long-term follow-up. Other investigators also reported high rates of success with this technique in limited follow-up studies.10,25,27–29

CONCLUSIONS

Lateral epicondylitis is a common cause of lateral elbow pain. Although controversy exists regarding the optimal treatment for this condition, in our hands, arthroscopic release of the ECRB origin with resection of the pathologic tendinosis tissue provides reproducible pain relief and allows patients to return to unrestricted activities. Other surgeons have reported similar short-term success with this technique with minor modifications.10,16,25,27-29 We have documented maintenance of successful outcomes at long-term follow up.21,22

Cadaveric studies have demonstrated the ability to resect the entire ECRB origin safely without violation of the important lateral ligamentous complex.35,36,42 The arthroscopic technique enables identification and treatment of coexistent intra-articular pathology. Successful operative treatment of lateral epicondylitis primarily depends on proper patient selection, identification of pathology, and complete resection of the ECRB tendinosis.

1. Runge F. Zur genese und behandlung des schreibekrampfes. Berl Klin Wochenschr. 1873;10:245-248.

2. Morris HP. Lawn-tennis elbow. Br Med J. 1883;2:557.

3. Boyd HB, McLeod ACJr. Tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1177-1182.

4. Coonrad RW, Hooper WR. Tennis elbow: its course, natural history, conservative, and surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1183-1187.

5. Nirschl RP, Pettrone FA. Tennis elbow: the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:832-839.

6. Baumgard SH, Schwartz DR. Percutaneous release of the epicondylar muscles for humeral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10:233-236.

7. Dunkow PD, Jatti M, Muddu BN. A comparison of open and percutaneous techniques in the surgical treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:701-704.

8. Grundberg AB, Dobson JF. Percutaneous release of the common extensor origin for tennis elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;376:137-140.

9. Savoie FH 3rd. Management of lateral epicondylitis with percutaneous release. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;2:243-246.

10. Szabo SJ, Savoie FH 3rd, Field LD, et al. Tendinosis of the extensor carpi radialis brevis: an evaluation of three methods of operative treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:721-727.

11. Yerger B, Turner T. Percutaneous extensor tenotomy for chronic tennis elbow: an office procedure. Orthopaedics. 1985;8:1261-1263.

12. Grifka J, Boenke S, Kramer J. Endoscopic therapy in epicondylitis radialis humeri. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:743-748.

13. Rubenthaler F, Wiese M, Senge A, et al. Long-term follow-up of open and endoscopic Hohmann procedures for lateral epicondylitis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:684-690.

14. Dunn JH, Kim JJ, Davis L, Nirschl RP. Ten-to-14 year follow-up of the Nirschl surgical technique for lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:261-266.

15. Khashaba A. Nirschl tennis elbow release with or without drilling. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:200-201.

16. Peart RE, Strickler SS, Schweitzer KMJr. Lateral epicondylitis: a comparative study of open and arthroscopic lateral release. Am J Orthop. 2004;33:565-567.

17. Zingg PO, Schneeberger AG. Debridement of extensors and drilling of the lateral epicondyle for tennis elbow: a retrospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:347-350.

18. Jobe FW, Cicotti MG. Lateral and medial epicondylitis of the elbow. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2:1-8.

19. Rosenberg N, Henerdon I. Surgical treatment of resistant lateral epicondylitis: follow-up study of 19 patients after excision, release and repair of proximal common extensor tendon origin. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:514-517.

20. Thornton SJ, Rogers JR, Prickett WD, et al. Treatment of recalcitrant lateral epicondylitis with suture anchor repair. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1558-1564.

21. Baker CLJr, Murphy KP, Gottlob CA, Curd DT. Arthroscopic classification and treatment of lateral epicondylitis: two-year clinical results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:475-482.

22. Baker CLJr, Baker CL 3rd. Long-term follow-up of arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:254-260.

23. Brooks-Hill AL, Regan RD. Extra-articular arthroscopic lateral elbow release. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:483-485.

24. Cummins CA. Lateral epicondylitis: in vivo assessment of arthroscopic debridement and correlation with patient outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1486-1491.

25. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indications, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:379-382.

26. Mullett H, Sprague M, Brown G, Hausman M. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: clinical and cadaveric studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;439:123-128.

27. Owens BD, Murphy KP, Kuklo TR. Arthroscopic release for lateral epicondylitis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:582-587.

28. Romeo AA, Fox JA. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: the 4-step technique. Orthop Tech Rev. 2002;4:206.

29. Sennoune B, Costa V, Dumontier C. Arthroscopic treatment of tennis elbow: preliminary experience with 14 patients. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2005;91:158-164.

30. Nirschl RP. Elbow tendinosis/tennis elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11:851-870.

31. Cyriax JH. The pathology and treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1936;18:921-940.

32. Goldie I. Epicondylitis lateralis humeri (epicondylalgia or tennis elbow): a pathogenetical study. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1964;57:339.

33. Kraushaar BS, Nirschl RP. Tendinosis of the elbow (tennis elbow): clinical features and findings of histological, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopy studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:259-278.

34. Regan W, Wold LE, Coonrad R, Morrey BF. Microscopic histopathology of chronic refractory lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:746-749.

35. Cohen MS, Romeo AA, Hennigan SP, Gordon M. Lateral epicondylitis: anatomic relationships of the extensor tendon origins and implications for arthroscopic treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:954-960.

36. Smith AM, Castle JA, Ruch DS. Arthroscopic resection of the common extensor origin: anatomic considerations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:375-379.

37. Calfee RP, Patel A, DaSilva MF, Akelman E. Management of lateral epicondylitis: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:19-29.

38. Mishra A, Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1774-1778.

39. Placzek R, Drescher W, Deuretzbacher G, et al. Treatment of chronic radial epicondylitis with botulinum toxin A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:255-260.

40. Pettrone FA, McCall BR. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy without local anesthesia for chronic lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1297-1304.

41. Stothers K, Day B, Regan WR. Arthroscopy of the elbow: anatomy, portal sites, and a description of the proximal lateral portal. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:449-457.

42. Kuklo TR, Taylor KF, Murphy KP, et al. Arthroscopic release for lateral epicondylitis: a cadaveric model. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:259-264.