6 Late effects of cancer treatment and survivorship

Medical late effects

Late effects are dependent upon the original cancer, its treatment, the family genetics and the developmental stage of the individual when treated for cancer. Box 6.1 lists some of the major effects that can occur.

Box 6.1

Medical late effects of treatment

| Second malignancy | e.g. leukaemia, sarcoma |

| Chronic health conditions | e.g. breathlessness, fatigue |

| Cardiological | e.g. arrhythmias |

| Neurological | e.g. peripheral neuropathy |

| Pulmonary | e.g. fibrosis |

| Endocrine | e.g. GH deficiency |

| Fertility | e.g. premature ovarian failure |

| Bone | e.g. osteoporosis |

| Renal | e.g. hypomagnesaemia |

Second malignancy

Second malignancies are the second most common cause of death (after the primary cancer) in those diagnosed with cancer, and can either be a solid tumour or haematological (leukaemia or myelodysplastic syndromes). The risk of second malignancy is increased with combinations of chemotherapy and radiotherapy but is also dependent upon the underlying genetics of the individual and the sensitivity of the tissue irradiated (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 The most common second malignancy after treatment for cancer and some of the identified or proposed causative agents

| Type of secondary malignancy | Identified or potential risk factors |

|---|---|

| Leukaemia | Chemotherapy, e.g. etoposide, anthracyclines |

| Sarcoma |

In general secondary solid tumours arise in sites of previous radiotherapy, especially if chemotherapy was also given. The total dose of radiotherapy delivered as well as the type and energy of the treatment and treated volume determine the risk. The tissues most likely to give rise to a secondary malignancy following radiotherapy are bone marrow, thyroid, breast and soft tissues (sarcomas) (Box 6.2).

Box 6.2

Learning points

Leukaemias and myelodysplastic syndromes have been found to relate to previous chemotherapy treatment, especially with etoposide, anthracyclines and alkylating agents. These leukaemias are characterized by a chromosomal abnormality at 11q23, tend to occur within 2 years of primary treatment and have a poor prognosis. Intensive regimens for Ewing’s sarcoma or rhabdomyosarcoma have a risk of up to 20% at 20 years of secondary haematological malignancy. Myelodysplastic syndromes have been associated with previous alkylating agents.

Example box 6.1

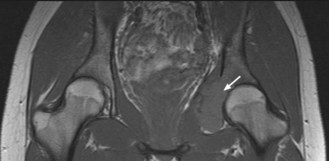

A 21-year-old woman was treated for Ewing’s sarcoma of the right pelvis with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, debulking surgery, radiotherapy and further chemotherapy. She had a good response to treatment with only a small mass remaining which remained stable on CT scans for 5 years. With increasing symptoms of pelvic and groin pain at 8 years an X-ray then MRI was performed which showed a mass in the left acetabulum (Figure 6.1). The appearance of the mass was not typical for a Ewing’s sarcoma and a biopsy was performed. The pathology showed an osteosarcoma. Despite staging showing no distant disease and treatment with chemotherapy, the tumour progressed rapidly, lung metastases developed and the patient died within a year.

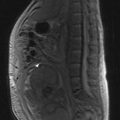

Infertility

Infertility as a consequence of cancer or its treatment remains a significant issue for young people who have not yet completed their families (Figure 6.2). The risk depends on the gender of the patient and the type of therapy administered as well as the type of cancer (Box 6.3). Overall the fertility of childhood cancer survivors when compared with their siblings is 0.76 for men and 0.93 for women.

Box 6.3

Risk of infertility in cancer survivors

The greatest risk to fertility in adult survivors is

In the UK, guidelines have been developed by a working party to highlight possible management strategies and risks of infertility with different cancer treatments (Box 6.4). These are available from the Royal College of Radiologist website (http://www.rcr.ac.uk/publications.aspx?PageID=149&PublicationID=269).

Box 6.4

Fertility options for women

There appears to be no significant increase in congenital abnormalities in the offspring of survivors, nor any increase in childhood cancers in the offspring, including after bone marrow transplantation (Box 6.5).

Bone late effects

Bone growth is affected by steroids, chemotherapy or radiotherapy (Box 6.6). In addition hormonal manipulation with aromatase inhibitors or anti androgen therapy can have profound consequences on bone loss. Osteopenia occurs frequently at the end of treatment with combination chemotherapy. In ER positive breast cancer where patients may have chemotherapy followed by an aromatase inhibitor, the hormonal treatment compounds the osteoporotic effect of the chemotherapy such that calcium supplementation or bisphosphonates are frequently required to prevent fractures. To minimize the risk of fractures from significant osteoporosis patients should be screened for osteoporosis prior to commencing hormonal treatment using a risk assessment and bone mineral density scan. Patients should be reassessed after 6–12 months on hormonal therapy. Those at significant risk should be advised about calcium in their diet and/or prescribed calcium supplements. At very high risk or after a fracture, bisphosphonates (orally or intravenously) should be prescribed.

Osteonecrosis is a known complication of treatment for leukaemia, lymphoma or bone marrow transplantation and is thought to be due to high-dose steroids. It tends to occur most in weight bearing bones e.g. femur such that arthroplasty of the hip joint may be carried out in up to 20% patients with femoral head osteonecrosis. Osteonecrosis of the jaw is a recognized complication of treatment with zolendronic acid. Patients should see a dental surgeon prior to starting treatment and zolendronic acid should be stopped and further dental assessments made if there is any suspicion of dental abscess.

Neurological

Hearing loss due to damage to the auditory nerve can occur with platinums, especially cisplatin, so that audiometry should be performed prior to and after treatment.

Example box 6.2

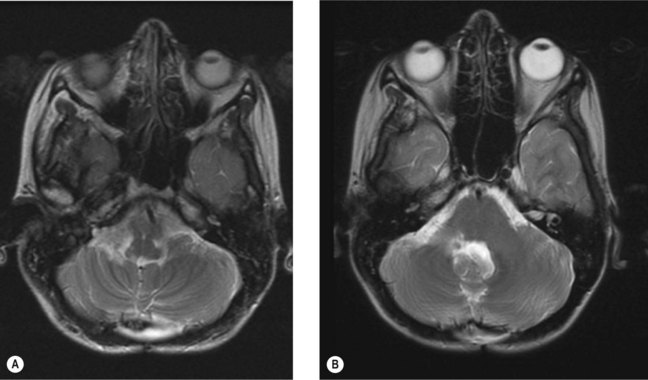

A 17-year-old man with medulloblastoma (Figure 6.3A) was treated successfully with combined chemo-radiotherapy followed by further chemotherapy. Although one of his presenting signs was of unsteadiness this deteriorated significantly part way through his chemotherapy such that he was unable to stand or walk unaided. Recurrence was suspected but the MRI (Figure 6.3B) showed no signs of this but showed scarring consistent with previous radiotherapy. On examination of the nervous system, there had been no change in the central features. However, a significant peripheral neuropathy had developed with loss of proprioception below the ankles and wrists. Unfortunately, although his MRI shows no evidence of recurrence 5 years later he has been left unable to walk out of the house unaided and is unable to work due to his peripheral neuropathy (Box 6.7).

Gastrointestinal

Following radiotherapy to the pelvis, or abdomen, acute toxicity to the bowel is well known due to inflammation of the intestinal organs. Late toxicity is often underestimated but accounts for significant morbidity (Box 6.8). Intermittent subacute bowel obstruction also occurs. All these symptoms can have a range of causes so referral to a gastroenterologist is recommended for appropriate investigation. Rectal bleeding in particular must not be ignored as this may represent a second malignancy, especially in those who have had pelvic radiotherapy.

Cardiological

Cardiac toxicity can take several forms following treatment including cardiac failure, arrhythmias and increased risk of myocardial infarction (Table 6.2). The major risk factors are mediastinal or left chest wall radiotherapy, anthracyclines and vincristine. Asymptomatic arrhythmias are common. Children treated with anthracyclines have reduced left ventricular wall thickness and reduced left ventricular function which can continue to deteriorate many years after treatment. Treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors has been shown to improve left ventricular function in the short term but did not prove effective in symptomatic patients in the longer term.

Table 6.2 Major cardiac problems associated with cancer treatments

| Nature of cardiac problem | Causative agent(s) |

|---|---|

| Arrhythmias (many asymptomatic with impact unknown) | Radiotherapy, multiple chemotherapy agents e.g. anthracyclines, taxanes |

| Cardiac failure |

Endocrine

Endocrine abnormalities can occur in any endocrine organ. The most frequently affected are those who have received radiotherapy close to the pituitary or thyroid (Table 6.3). Hormonal replacement may be necessary for these patients as the hormones involved have significant systemic functions. Abnormalities do not occur immediately after treatment, particularly those from the pituitary or thyroid, so they should be screened for starting at least 1 year post treatment or earlier with symptoms. Adrenal insufficiency should always be considered in patients who have received high-dose steroids, particularly during a period of infection.

Table 6.3 Overview of most common endocrine abnormalities and their cause

| Endocrine organ affected | Hormones affected | Causative agent |

|---|---|---|

| Pituitary |

Endocrine input is essential in the assessment of late effects in the follow-up clinic.

Causes of death after cancer treatment

The main cause of death following a diagnosis of cancer is the cancer itself even after surviving over 5 years from diagnosis. After recurrence the greatest risk of death is from a second malignancy followed by pulmonary then cardiac problems. In one study the standardized mortality ratio was 19.4 for second malignancy, 8.2 for cardiac death and 9.2 for pulmonary death with other causes at 3.3. The risk of death was greatest for women, those diagnosed before age 5 and those with an initial diagnosis of leukaemia or CNS tumour. Given the recent change in treatment to reduce mediastinal radiotherapy (a major cause of these sequelae in Hodgkin’s disease) it is hoped that these will reduce in the future.

Ganz PA. Cancer survivorship. Today and Tomorrow. Springer Press; 2007. ISBN-10: 0-387-34349-0

Mertens A, Yasui Y, Neglia J, et al. Late mortality in Five-year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: The childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;13:3163-3172.

. Expert guidance on fertility: The effects of cancer treatment on reproductive functions. Guidance on management. Report of a Working Party. Available from http://www.rcr.ac.uk/publications.aspx?PageID=149&PublicationID=269