Chapter 24 Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: techniques and results

1 INTRODUCTION

Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty (LAUP) is a surgical procedure for the treatment of snoring and mild obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) that involves a sequential reduction and reshaping of the tissues of the uvula and soft palate. Initially described by Dr Yves-Victor Kamami in 1986, LAUP has been widely performed in the United States since 1993 to remove excessive vibratory tissue of the velopharynx.1 This procedure can often be performed in the office setting under local anesthesia in one to four stages that are typically 6 weeks apart.

2 PATIENT SELECTION

A complete head and neck physical examination should include calculation of a Body Mass Index (BMI), measurement of the neck circumference, and flexible laryngo-scopy. During an exam for all sleep disordered breathing patients, the surgeon must attempt to identify the site or sites of potential obstruction. All patients considering LAUP should also undergo some formal objective sleep assessment. The Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends a preoperative polysomnogram or cardiorespiratory study prior to LAUP.2

There are several key features that can help a practitioner identify the ideal patient for LAUP. First, polysomno-graphy should reveal the patient to either be a non-apneic snorer or have mild obstructive sleep apnea. Although some studies have shown benefit in patients with moderate and severe OSAS, the long-term outcomes in the improvement of objective indices are controversial. Although the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery declared that LAUP is considered a part of the comprehensive management of adults with OSAHS in 1997, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine did not recommend LAUP for the treatment of sleep-related breathing disorders in 2000.3

A third important selection factor is the patient’s BMI. Rollheim and colleagues were able to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in snoring outcomes 3 months after surgery in patients with a BMI less than 28 kg/m2 as compared to those with a BMI greater than or equal to 28 kg/m2.4 This disparity is most likely related to a greater incidence of obstruction at levels other than the soft palate in patients with a higher BMI, and thus persistent snoring.

There are also several more subtle patient factors to consider in patient selection. Patient co-operation is essential tosuccess if the procedure is to be performed in an outpatient setting. A nervous patient or one with an uncontrollable gag reflex may not be able to tolerate one, or even several, procedures. A small mouth opening or trismus may limit the surgeon’s access to the oropharynx. Lastly, any medical condition, such as a hemostatic disorder, that may decrease the safety of the procedure should be considered a relative contraindication. In the above circumstances, the procedure alternatively may be conducted in the operating room under general anesthesia.

3 PROCEDURE

When initially described by Kamami, the LAUP procedure consisted of two paramedian vertical incisions extending superiorly from the free edge of the soft palate.5 The uvula was largely resected in order to reshape a new, shorter one. This French method was later modified by Woolford and Farrington.6 Their British technique involved vaporization of a strip of mucosa from the uvula to the hard palate. This area is left bare to contract and scar, resulting in increased rigidity of the velum soft tissues. The authors prefer to utilize both modifications, often in a sequential, staged fashion. The following procedure is described with a CO2 laser, but other lasers and cutting/coagulating instruments can also be used, such as electrocautery.

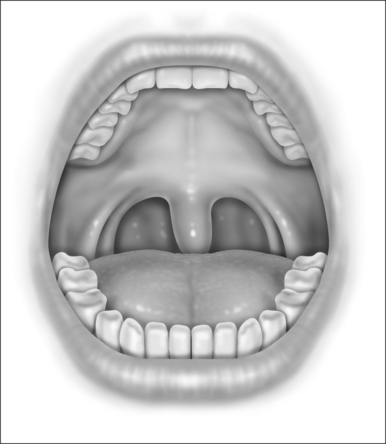

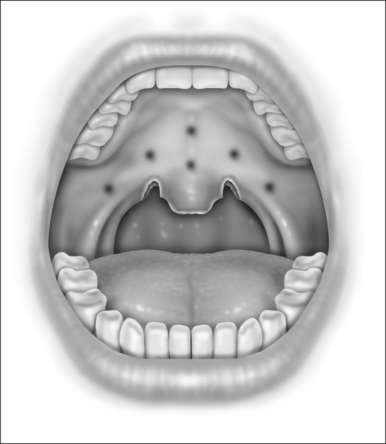

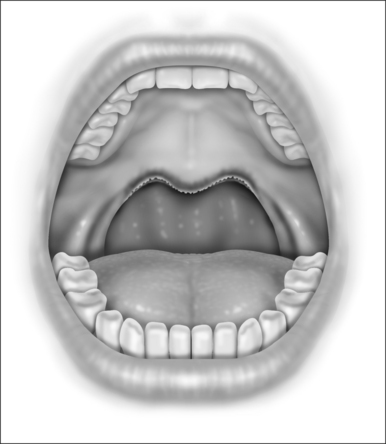

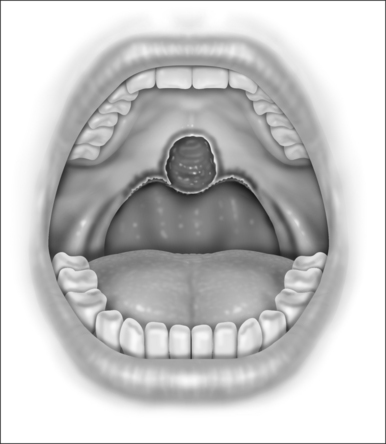

With the patient in the upright, sitting position, a topical anesthetic spray (benzocaine) is generously applied to the oropharynx (Fig. 24.1). Next, lidocaine 1% with epinephrine (1:100,000) is infiltrated into the base of the uvula, posterior soft palate, and the superior aspect of the tonsillar pillars (Fig. 24.2). The injected volume is small (approximately 3 ml) since soft tissue distortion and added water content may compromise the surgeon’s ability to precisely shape the palate. To minimize the painful burning associated with infiltration, the lidocaine may be mixed with bicarbonate solution (9:1 ratio) prior to injection. Further anesthetic may be readministered to alleviate any discomfort during the procedure.

The authors use a CO2 laser to perform the surgery (Lumenis 30-C CO2 Laser, Lumenis, Inc, New York, New York). Lasers of other wavelengths can be used as well. The hand piece has a ‘backstop’ that protects the posterior pharyngeal mucosa from inadvertent injury. A typical laser setting is 20 watts with a focused beam in a continuous mode. The patient and all members of the surgical team must wear eye protection prior to laser deployment.

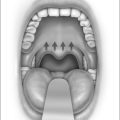

Initially, the laser is used to create vertical trenches in the soft palate on either side of the root of the uvula. From inferior to superior, a through-and-through incision cutting the oral and nasal mucosa of the soft palate and the intervening soft tissue is made (Fig. 24.2). The length of the trench should be guided by the patient’s anatomy. Typically, the palatal musculature is not exposed. The tip of the uvula is obliterated and made to take on the desired contour (a scanning beam is helpful but not essential for this).

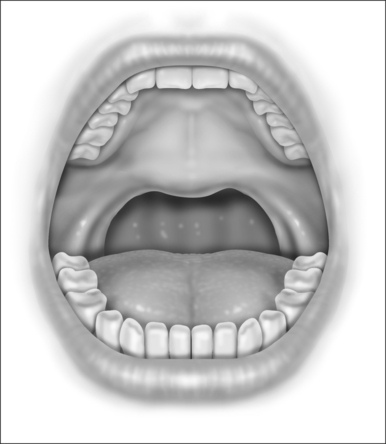

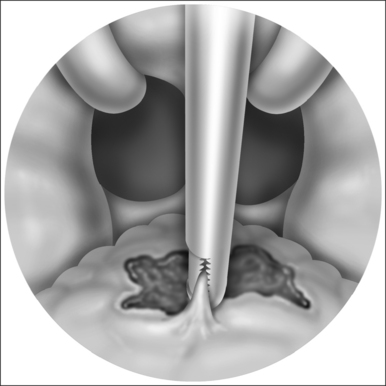

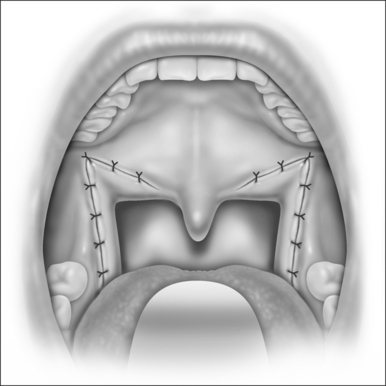

Next, the thickness of the uvula and free edge of soft palate is reduced by excision of the submucosal tissue and part of the uvularis muscle. The anterior uvular mucosa is grasped and rotated superiorly so that the tissue between the oral and nasal mucosa can be reduced with a scanning laser beam. By ‘fish mouthing’ the uvula, the anterior and posterior mucosa are left intact and will heal with minimal granulation at the free edge. These tissues then subsequently scar and contract over the subsequent weeks (Fig. 24.3).

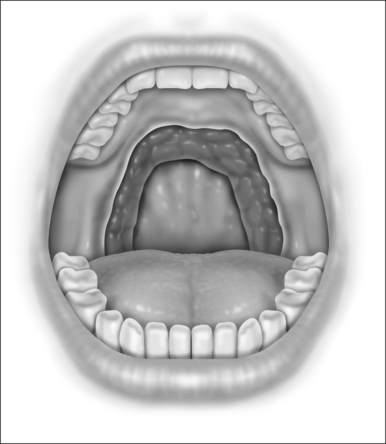

The laser is a useful tool for this procedure mainly becausecontrolled tissue incision and obliteration can be performed with great accuracy. Especially with the protective backstop, collateral tissue damage is quite minimal. It is clear, moreover, that the surgical result and patient outcomes are technique sensitive; precision in tissue reduction and contouring is essential. Specific caution should be exercised to avoid a circumferential wound or continuous raw surface that will predispose to pharyngeal contraction and stenosis (Fig. 24.4). Extensive and imprecise mucosal obliteration will not only lead to failure of symptomatic improvement, but also increase the chance of complications.

For subsequent stages, the vertical trenches can be serially recreated and extended to obtain the desired contour and symptomatic improvement (Fig. 24.5). The uvula, in general, should be conservatively addressed after the initial stage. Furthermore, the British method of soft palate mucosal vaporization can be used as an adjunct in second or third stages. The scanning beam of the laser is used with a power setting of 20W. Approximately 2cm of mucosa and submucosa on the oral side of the soft palate and uvular base is vaporized (Fig. 24.6). The underlying median raphe and palatal musculature should, however, be carefully preserved. Subsequent scarring of this bare area may result in increased rigidity of the velum so that it may resist collapse and vibration during inspiration.

4 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Prior to discharge, an examination of the pharynx confirms hemostasis. A mild narcotic with acetaminophen (e.g. hydrocodone) is used for pain management and the patient maintains 5 days of oral antibiotics. The patient is instructed to avoid aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Furthermore, a viscous lidocaine (2%) solution may be used every 2 hours as a mouth rinse to reduce the pain.

In general, this procedure produces a significant amount of postoperative pain and discomfort. Although this improves with convalescence, several days of throat pain necessitating narcotics are common. Although LAUP may be perceived as less painful than uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), pain from both procedures is approximately equivalent in both severity and duration to UPPP.7 The patient should, therefore, be appropriately counseled preoperatively and treated with appropriate narcotics postoperatively.

Oral sucralfate, a drug used for peptic ulcer disease, has been recently shown to reduce pain after LAUP. Sucralfate adheres to proteins at the ulcer site and forms a viscous adhesive barrier on the surface of injured mucosa, resulting in a cytoprotective effect. When 5 ml of sucralfate (1 g/5mL) was gargled for 5 minutes every 6 hours, there was a statistically significant improvement in throat pain, oral analgesic requirement, and return to normal diet in a randomized controlled trial.8

5 COMPLICATIONS

Although laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty is considered a relatively safe procedure, complications including persistent foreign body sensation, pharyngeal dryness, postoperative hemorrhage, infection, palatal incompetence, taste alteration, nasopharyngeal stenosis, and even airway compromise or death can occur. The overall complication rate for the procedure is 3.5%;9 since a patient undergoes several serial procedures, the complication rate for a given individual may be slightly higher.

Because of the inherent vascularity of the soft palate, hemorrhage is the most common complication after LAUP and occurs in 2–3% of patients. In a study of 754 LAUP procedures by Walker and Gopalsami, 16 patients (2.1%) developed postoperative hemorrhage.9. All of these patients bled within 48 hours of a procedure, with the vast majority occurring within 24 hours. None of the cases necessitated blood transfusion and the site of bleeding was always the apex of the parauvular vertical trench. Approximately half of the patients required no medical intervention as the bleeding ceased spontaneously. The remainder were controlled with silver nitrate cautery or suture ligation.

6 RESULTS

6.1 SNORING

The LAUP procedure has been conventionally used in the treatment of snoring without obstructive sleep apnea. The initial report on LAUP by Kamami5 revealed that 77% of non-apneic snorers had complete or near-complete resolution of snoring. A follow-up study by Walker and colleagues10 echoed these results. In their series, 60% of 105 snorers had total or near-total elimination of snoring, with an additional 29% who reported partial improvement. Other studies show patient satisfaction ranging from 60% to 84%.1 However, the surgical techniques, timing of serial sessions, and criteria for ‘cure’ differed among these studies and may limit extrapolation of this information.

Quality of life data from several studies also indicate an improvement corresponding to decreased snoring. Armstrong and colleagues demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in quality of life for the patient and bedpartner for non-apneic snorers who underwent LAUP.11 Another study revealed that 72% of bedpartners were satisfied with the procedure, and close to two-thirds no longer slept in separate rooms.12 As most patients often seek medical attention for the sake of their bedpartner, these data realize the main outcome for which they seek care.

Few studies have analyzed the long-term effectiveness of LAUP. The problem with such longitudinal assessments is the presence of other confounding variables. The patient’s body habitus, for example, may change with time or new-onset nasal obstruction may develop. Furthermore, a bed-partner’s retrospective recall of snoring severity may become unreliable over time. Mickelson and Ahuja reported an initial total to near-total improvement in snoring in 90% of their patients at 6 to 12 weeks.13 However, when these patients were re-evaluated after 2 years, the effectiveness was reduced to 62%. In a Thai study, Neruntarat analyzed long-term outcomes in 340 non-apneic snorers that underwent LAUP.14 Although a small portion of his cohort underwent adjunctive procedures (e.g. tonsillectomy, turbinate reduction), 75% of patients had at least a 50% improvement in their snoring after 3 years. More prospective study with standardized techniques and grading criteria is definitely necessary to reliably establish long-term effectiveness.

Patient selection is an integral element in achieving good outcomes and patient satisfaction. As mentioned earlier, careful preoperative assessment localizing the velum as the primary level of upper airway obstruction will improve success. In a similar vein, patients with a BMI under 28 kg/m2 will also have more statistically significant snoring improvement than those above 28 kg/m2.4 It is likely that patients with a higher BMI will have secondary levels of obstruction other than the soft palate, resulting in LAUP failure.

6.2 OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA

LAUP may be a reasonable treatment option for carefully selected patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Mickelson and Ahuja13 studied a cohort of 36 patients who underwent LAUP for obstructive sleep apnea. In postoperative sleep studies, the Apnea Index decreased from 14.4 to 5.8 and the respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI) decreased from 28.1 to 17.9, both of which were statistically significant. The RDI decreased by at least 50% in 39% of patients overall and 44% of patients dropped to less than 10 events per hour. Another study by Walker and associates15 confirmed these findings. Their study of 38 patients revealed that surgical response rates, as defined by 50% decrease in RDI and postoperative RDI less than 20, were seen in 47% of mild apneics, 42% of moderate apneics, and 46% of severe apneics.

There are other studies, however, that temper the enthusiasm for LAUP as a standard treatment in the sleep apnea algorithm. When evaluating 44 consecutive patients with mild to moderate OSA, Ryan and Love found that only 27% of patients had a good response to LAUP in postoperative sleep studies performed at least 3 months after intervention.16 Subjective improvements in quality of life and daytime somnolence were present, but the snoring index did not show statistically significant improvement. Moreover, 30% of their patients were worse and had an AHI twice that of their preoperative sleep study. This unusual finding also occurred in a study by Finkelstein and colleagues.17 In their study of 26 patients, 31% actually had a worsening of the post-procedure RDI. They surmised that velopharyngeal narrowing from progressive palatal fibrosis might actually aggravate obstruction in some individuals and, thereby, worsen their sleep apnea. Indeed, a review of illustrations confirms that assumption and highlights the need to avoid circumferential scarring. Long-term satisfaction after LAUP appears to be dependent on technique and patient selection, the two most crucial aspects to successful outcomes.

1. Remacle M, Betsch C, Lawson G, et al. A new technique for laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: decision-tree analysis and results. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:763-768.

2. Littner M, Kushida CA, Hartse K, et al. Practice parameters for the use of laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: an update for 2000. Sleep. 2001;24:603-619.

3. Walker RP. Laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty. In: Fairbanks D, Mickelson SA, Woodson BT, editors. Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003:144-150.

4. Rollheim J, Miljeteig H, Osnes T. Body mass index less than 28 kg/m2 is a predictor of subjective improvement after laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty for snoring. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:411-414.

5. Kamami Y. Laser CO2 for snoring, preliminary results. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1990;44:45-56.

6. Woolford T, Farrington T. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty – the British method. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;5:292-293.

7. Troell RJ, Powell NB, Riley RW, et al. Comparison of postoperative pain between laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, and radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the palate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:402-409.

8. Kyrmizakis DE, Papadakis CE, Bizakis JG, et al. Sucralfate alleviating post-laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty pain. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:55-58.

9. Walker RP, Gopalsami C. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: postoperative complications. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:834-838.

10. Walker RP, Grigg-Damberger MM, Gopalsami C, et al. Laser-assisted uvuloplasty for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: results in 170 patients. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:938-943.

11. Armstrong MW, Wallace CL, Marais J. The effect of surgery upon the quality of life in snoring patients and their partners: a between-subjects case-controlled trial. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1999;24:510-522.

12. Prasad KR, Premraj K, Kent SE, Reddy KT. Surgery for snoring: are partners satisfied in the long run? Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2003;28:497-502.

13. Mickelson SA, Ahuja A. Short-term objective and long-term subjective results of laser-assisted uvuloplatoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:362-367.

14. Neruntarat C. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: short-term and long-term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:90-93.

15. Walker RP, Garrity T, Gopalsami C. Early polysomnographic findings and long-term subjective results in sleep apnea patients treated with laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1438-1441.

16. Ryan CF, Love LL. Unpredictable results of laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax. 2000;55:399-404.

17. Finkelstein Y, Stein G, Ophir D, et al. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty for the management of obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:429-434.