Chapter 24 Large bowel cancer

Introduction

Bowel cancer screening

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common forms of cancers in the Western world. Lifetime risk to age 75 in the general population is 1:17 for men and 1:26 for women in Australia and is the second leading cause of death.1

Research shows that the risk of developing bowel cancer rises significantly from the age of 50 and accounts for 85% of sporadic cancers.2

Most cancers of the bowel arise from polyps (adenomas) and removal of polyps markedly reduces the subsequent risk of disease.3

Various countries are in the process of introducing national screening programs, and in Australia a population of greater risk are invited to take part in the program.1

The eligible population in Australia is those turning 50, 55 and 65 years of age between January 2008 and 31 December 2010. In the US, screening will commence at a similar age (50).4 People eligible to participate in the program will receive an invitation through the mail to complete a faecal occult blood test (FOBT) and no cost is involved. There is controversy as to which is the best screening method and also which is the best FOBT.2,5,6 In the US, FOBT will also be used.

There is also increasing evidence to support the use of virtual colonoscopy as an initial screening test.7

If the FOBT is positive, the participant will be advised to discuss the result with their doctor who will generally refer them for a colonoscopy.4 Doing an FOBT every 2 years can reduce the risk of dying from bowel cancer by up to one-third.2

High-risk patients such as those with familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary non-polyposis CRC need to be screened more frequently. As with all other screening tests, there needs to be an emphasis on combining screening with prevention, in particular with CRC where there is considerable research data on prevention.8

Lifestyle and prevention

The importance of prevention has been highlighted by Baker and Wardle, even suggesting that lifestyle changes could prevent more colorectal than screening.8 Key lifestyle and dietary factors for primary prevention are:

Behavioural factors

Personality factors, especially emotional suppression and loss (and a feeling of hopelessness), have been linked to the occurrence and progression of cancer. Hence, as with almost all chronic illness, behavioural factors have been reported to be important in CRC.9, 10

Recently a population-based prospective cohort study from Denmark investigated associations between personality traits and cancer survival.11 This study showed that neuroticism was negatively associated with cancer survival. A further recent study reported that certain personality factors may not be a risk factor for CRC in the Japanese population. However the report concluded that an ambivalent connection and egocentricity may be protective.12

Physical activity/exercise

Regular and vigorous physical exercise has been scientifically established as being a strong preventative factor against cancer with the potential to reduce incidence by 40%.13 With respect to bowel cancer, physical activity can decrease its incidence by 50%, independent of diet and body weight.14

Mind-body medicine

The diagnosis of cancer presents a major and stressful life event that necessitates an adaptive adjustment to sustain quality of life. A fundamental goal is to enhance quality of life while striving to prolong life. Quality of life has been reported to predict survival in patients with advanced large bowel cancer.15

Surveys of patients with cancer repeatedly identify information provision as a major unmet need. Research has shown that the provision of adequate information is related to an increase in psychological wellbeing.16 Effective communication skills ensure that this information is clearly explained and understood.

There is incontrovertible evidence from 3 meta-analysis of the benefits of psychological interventions in patients with cancer. Such interventions improve emotional adjustment (including anxiety and depression, sense of control, self-esteem), functional status (including daily living activities, social and disease-related symptoms (e.g. like nausea. vomiting, pain) and overall quality of life.17, 18, 19

There are wide benefits from relaxation-based therapies in reducing anxiety, treatment-related phobias, conditioned nausea and vomiting and insomnias.13

Both cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and supportive expressive therapy are effective in countering existential fears of dying, aloneness, meaninglessness, and unrealistic fears about the processes of treatment.13–16

Nutritional influences

Diet

Excess energy intake/fat and carbohydrates

Execss energy intake has been shown to be consistently associated with bowel cancer.20

Fat intake is closely associated with energy intake, it has been difficult to differentiate between the two, to add to this confusion a meta-analysis found little evidence of any energy-independent effect of either total or saturated fat.21

Several prospective, observational studies have shown that diet is a major factor in the aetiology of large bowel cancer, with high fish consumption highlighted as decreasing CRC risk. A problem with most of the older studies has been that fats, such as those from fish fats which have been shown to be protective in more recent studies, were not differentiated from other fats.22, 23

A recent randomised clinical trial (RCT) objectively investigated the effects of a 6-month intervention with oil-rich or lean fish versus dietary advice only, on apoptosis and mitosis within the colonic crypt. The participants had either colorectal polyps, inactive ulcerative colitis, or no macroscopic signs of disease.24 The results of the trial showed that the total number of mitotic cells per crypt decreased non-significantly in the salmon group and in the cod group compared with the dietary-advice-only group. The study concluded that an increase in the consumption of either oil-rich or lean fish to 2 portions weekly over 6-months did not markedly change apoptotic and mitotic rates in the colonic mucosa. Moreover it should be noted that fish fats consumption may be a lifetime strategy, not just a short-term solution. A recent review unequivocally concludes that intake of fish fats has a favourable effect on lowering cancer risk.25

High consumption of trans-fatty acids is linked to colorectal adenomas.26

There is confusion as to whether carbohydrate intake can influence CRC, but it would be very unlikely that refined carbohydrates were not a risk factor.27, 28

Meat

A meta-analysis of studies on meat and CRC risk showed that it is a risk factor. Much of the risk was associated with processed meat.29

Dietary fibre

An inverse correlation between plant food and intake in cancer risk in 8 of 10 case-controller cohort studies has been published.30

A systematic review of case-control studies found that 12 out of 13 showed a decreased risk of CRC with increased fibre intake.31

A huge and more recent study of 519 978 participants also showed that fibre intake reduced risk.32

Nutritional supplements

Micronutrients

Folic acid

The Nurses Health Study of nearly 90 000 nurses showed an inverse relationship between incidence of colon cancer and dietary folate intake.39 A strong association of alcohol intake with CRC cancers and adenomas have been shown to be associated with low folate and methionine.40

Dietary folate can modify the risk of alcohol consumption on breast cancer, and hence it is possible that folate supplementation could also protect for CRC.41

There is controversial evidence indicating that folate supplementation, later in life, may increase the risk of CRC and possibly other cancers.42

Vitamin B6

An inverse association between intake of dietary vitamin B6 and CRC were shown in a longitudinal study especially in women consuming moderate to excess alcohol.43

Probiotics/prebiotics

Probiotics and prebiotics are likely to be protective, in particular as they greatly influence the internal bowel environment.48

A number of studies demonstrate that probiotics alter bowel microflora and decrease premalignant and malignant lesions in laboratory experiments in animal studies.49, 50

Radiation enteritis is a severe problem in patients receiving irradiation of the abdomen or pelvis in the course of cancer treatment. Experimental studies in animal models and clinical trials of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have consistently shown that the use of probiotic organisms may effectively down-modulate the severity of intestinal inflammation by altering the composition and metabolic and functional properties of indigenous flora of the gut.51 Recently a multi-centre randomised study demonstrated that nutritional intervention with the probiotic drink containing L. casei DN-114 001 does not reduce the incidence of radiation-induced diarrhoea as defined by a Common Toxicity Criteria Grade 2 or greater. However, it had a significant effect on stool consistency as measured by the Bristol scale.52 However an earlier study with 490 patients who underwent adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy after surgery for sigmoid, rectal, or cervical cancer and who were assigned to either the high-potency probiotic preparation VSL#3 (one sachet 3 times a day [tid]) or placebo starting from the first day of radiation therapy showed that with a multi-strain preparation it protected cancer patients against the risk of radiation-induced diarrhoea.53

Phytonutrients

There are several naturally occurring compounds on foods of plant origin (vegetables, fruit, cereals and tea) that have strong protective effects against CRC in addition to their protection from their fibre content.54, 55 Of particular interest are the cruciferous vegetables, onion family, leafy vegetables, tomatoes, as well as fruits and cereals containing carotenoids, vitamin C and E.46 Phytonutrients include carotenoids, vitamin C, vitamin E, folate, indoles, allylic sulphides and lycopene.

Selenium

A multi-centre, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled cancer-prevention trial was designed to investigate if selenium supplementation could decrease skin cancer incidence.56 This trial found a highly significant reduction of CRC when using a daily dose of selenium of 200mcg.

Another study has shown that selenium levels related inversely to the large adenomas, but this has been confirmed in a nested case-controlled study.57, 58

Vitamins E and C

Several dietary antioxidants such as tea polyphenols, curcumin, genistein, resveratrol, lycopene, pomegranate and lupeol can re-stabilise and modulate cellular metabolic function. A case-control study from Melbourne (Australia) found that dietary micronutrients involved in DNA methylation (folate, methionine and vitamins B6 and B12) and some of those with antioxidant properties (selenium and vitamins E and C) may have a role to play in lowering colorectal cancer risk.59

Stone and Papas highlight the difference between alpha-tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol, and that the latter may be more protective.60

Gamma-tocopherol is a major form of vitamin E in Western diets and has found to be an anti-inflammatory agent plus directly inhibits cyclooygenase-2 (COX-2) activity and this may be another way in which it could be protective.61 These authors highlight the important difference between the synthetic dl-alpha-tocopherol acetate and the natural form.

An earlier meta-analysis of 5 prospective nested, case-control studies indicated that high serum levels of alpha-tocopherol were associated with a modest decrease in subsequent incidence of CRC.62 A more recent study, the large Nurses Health Study, found that 300IU/day of supplemented vitamin E mainly protects CRC in men but not in women.63 A population-based control study of patients with rectal cancer from the US showed that vitamin E and lycopene may reduce the risk of rectal cancer.64

More recently, in 4 major trials involving beta-carotene, vitamin C and synthetic alpha- tocopherol vitamin E, or vitamin C and E or beta-carotene, and vitamin C and E, the latter study involved those with familial adenomatous polyposis. All studies showed no benefit.65–68

Herbs

Liquorice

A recent study found that liquorice prevented CRC in mice.70 COX-2 derived PGE2 promotes CRC regression, and both non-selective COX inhibitors (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) and selective COX-2 inhibitors (Celecoxib) reduces the size and numbers of colonic adenomas. However, increased gastrointestinal side-effects of NSAIDs and increased cardiovascular risk of selective COX-2 inhibitors limit their use in chemo-prevention of CRC.

The findings of Zhang et. al. suggest that the enzyme inhibition may be a potentially therapeutic option in CRC.71

Conclusion

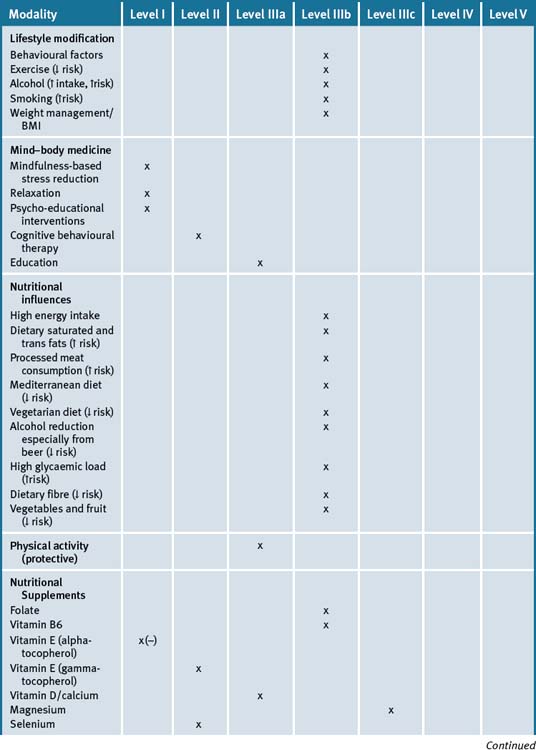

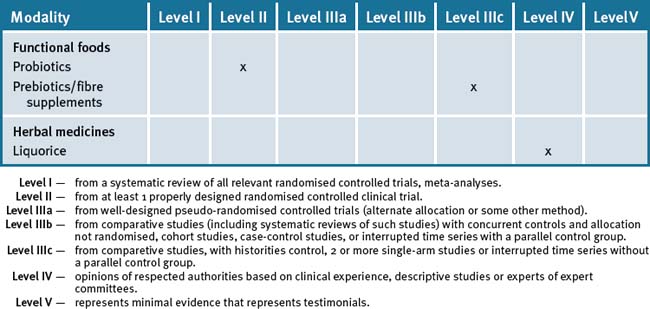

Clinicians cannot only provide assistance with early detection but may also provide significant input into the prevention of large bowel cancer by helping people with lifestyle factors that have an overall effect of reducing the risks as well as allay unreasonable and perceived fears associated with treatments. Table 24.1 summarises the current evidence for CAM treatments.

Clinical tips handout for patients — large bowel cancer

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine (most helpful)

Rest and stress management

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Fish oils

Vitamins and minerals

Vitamin B6

Vitamin C

Natural vitamin E

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol)

Magnesium and calcium (best provided together)

Selenium (sodium selenite, organic selenium found in yeast)

Probiotics

Prebiotics/fibre

Oligofructoses are plant sugars from a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, and cereals.

1 Dept Health and Ageing. Bowel cancer screening. Cancerscreening. Online. Available: www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/content/bowel-a (accessed July 2009)

2 Bolin T., Cowen A.E., Korman M.G. Colorectal cancer prevention. MJA. 2002;176:145-146.

3 Winawer S.J., Zauber A.G., Ho M.N., et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Eng J Med. 1993;329:1977-1981.

4 Dept Health and Ageing. Colorectal cancer. Cancer topics. Online. Available: www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/prevention/colorectal (accessed July 2009).

5 Ahlquist D.A., Sargent D.J., Loprinzi C.L. Stool DNA and occult blood testing for screen detection of colorectal neoplasia. Ann Int Med. 2008;149:4412-4450.

6 Young G.P., Cole S.R. Which faecal occult blood test is best to screen for colorectal cancer? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:140-141.

7 Summers R., Yao J., Pickhardt P., et al. Computer tomographic virtual colonoscopy computer-aided polyp detection in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1832-1844.

8 Baker A.H., Wardle J. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake among adults attending colorectal cancer screening: the efficacy of a brief tailored intervention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:203-206.

9 Kune S., Kune G.A., Watson L.F., et al. Recent life change and large bowel cancer. Data from the Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:57-68.

10 Kune G.A., Kune S., Watson L.F., et al. Personality as a risk factor in large bowel cancer: data from the Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study. Psychol Med. 1991;21:29-41.

11 Nakaya N., Hansen P.E., Schapiro I.R., et al. Personality traits and cancer survival: a Danish cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(2):146-152.

12 Nagano J., Kono S., Toyomura K., et al. Personality and colorectal cancer: the Fukuoka colorectal cancer study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38(8):553-561.

13 Newton R.U., Galvao D.A. Exercise in prevention and management of cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008;9(2–3):135-146.

14 Colditz G.A., Cannuscicc C.C., Frazier A.L. Physical activity and reduced risk of colon cancer: implications for prevention. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:649-667.

15 Maisey N.R., Norman A., Watson M., et al. Baseline quality of life predicts survival in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(10):1351-1357.

16 Smith J.R., Mugford M., Holland R., et al. A systematic review to examine the impact of psycho-educational interventions on health outcomes and costs in adults and children with difficult asthma. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(23):iii-iiv.

17 Devine E.C., Westlake S.K. The effects of psychoeducational care provided to adults with cancer: meta-analysis of 116 studies. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(9):1369-1381.

18 Sheard T., Evans J., Cash D., et al. A CAT-derived one to three session intervention for repeated deliberate self-harm: a description of the model and initial experience of trainee psychiatrists in using it. Br J Med Psychol. 2000;73:179-196.

19 Spiegel D., Bloom J.R., Kraemer H.C., et al. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;2(8668):888-891.

20 Willett W.C., Stampfer M.J., Colditz G.A., et al. Relation of meat, fat, and fibre intake to the risk of colon cancer in a prospective study among women. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1664-1672.

21 Howe G.R., Aronson K.J., Benito E., et al. The relationship between dietary fat intake and risk of colorectal cancer: evidence from the combined analysis of 13 case-control studies. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:15-28.

22 Hall M.N., Chavarro J.E., Lee I.M., et al. A 22–year prospective study of fish, n-3 fatty acid intake, and colorectal cancer risk in men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1136-1143.

23 Norat T., Bingham S., Ferrari P., et al. Meat, fish, and colorectal cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into cancer and nutrition. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:906-916.

24 Pot G.K., Majsak-Newman G., Geelen A., et al. Fish consumption and markers of colorectal cancer risk: a multicenter randomised controlled trial. AJCN. 2009;90(2):354-361.

25 Pauwels E.K., Kairemo K. Fatty acid facts, part II: role in the prevention of carcinogenesis, or, more fish on the dish? Drug News Persp. 2008;21(9):504-510.

26 Vinikoor L.C., Schroeder J.C., Millikan R.C., et al. Consumption of trans-fatty acid and its association with colorectal adenomas. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:289-297.

27 Higginbotham S., Zhang Z.F., Lee I.M., et al. Dietary glycemic load and risk of colorectal cancer in the Women’s Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:229-233.

28 Fuchs C.S., Giovannucci E.L., Colditz G.A., et al. Dietary fibre and the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma in women. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:169-176.

29 Sandhu M.S., White I.R., McPherson K. Systematic review of the prospective cohort studies on meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analytical approach. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:439-446.

30 Potter J.D. Nutrition and colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:127-146.

31 Howe G.R., Benito E., Castelleto R., et al. Dietary intake of fibre and decreased risk of cancers of the colon and rectum: evidence from the combined analysis of 13 case-control studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:1887-1896.

32 Bingham S.A., Day N.E., Luben R., et al. Dietary fibre in food and protection against colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): an observational study. Lancet. 2003;361:1496-1501.

33 IARC (International Agency for Cancer on Research). Cruciferous vegetables, Isothiocyanates and Indoles. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention; 2004. 9 (Leon IARC)

34 Cassidy A., Bingham S.A., Cummings J.H. Starch intake and colorectal cancer risk: an international comparison. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:937-942.

35 Muir J.G., Yeow E.G.W., Keough J., et al. Combining wheat bran with starch resistance has more beneficial effects on fecal indixes than does wheatbran alone. AJCN. 2004;79:1020-1028.

36 Giovannucci E., Ascherio A., Rimm E.B., et al. Physical activity, obesity, and risk for colon cancer and adenoma in men. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:327-334.

37 Chao A., Thun M.J., Jacobs E.J., et al. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer mortality in the cancer prevention study II. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1888-1896.

38 American Institute for Cancer Research. World Cancer Research Fund. Food, nutrition and the prevention of cancer. A global prospective. London: American Institute for Cancer Research and World Cancer Research Fund; 1997.

39 Giovannucci E., Stamfer M.J., Colditz G.A., et al. Multivitamin use, folate, and colon cancer in women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:517-524.

40 Giovannucci E. Epidemiologic studies of folate and colorectal neoplasia: a review. J Nut. 2002;132:2350S-2355S.

41 Baglietto L., English D.R., Gertig D.M., et al. Does dietary folate intake modify effect of alcohol consumption on breast cancer risk? Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331:807-814.

42 Hubner R.A., Houlston R.S. Folate and colorectal cancer prevention. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:233-239.

43 Larsson S.C., Giovannucci E., Wolk A. Vitamin B6 intake, alcohol consumption, and colorectal cancer: a longitudinal population-based cohort of women. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1830-1837.

44 Wei E.K., Giovannucci E., Salhub J., et al. Plasma vitamin B6 and the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:684-692.

45 Peters U., Hayes R.B., Chatterjee M., et al. Circulating vitamin D and metabolites, polymorphism in vitamin D receptor, and colorectal adenoma risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:546-552.

46 Harris D.M., Go V.L. Vitamin D and colon carcinogenesis. J Nutr. 2004;134(12 Suppl):3463S-3471S.

47 Dai Q., Shrubsole M.J., Sess R.M., et al. The relation of magnesium and calcium intakes and a genetic polymorphism in the magnesium transporter to colorectal neoplasia risk. AJCN. 2007;86:743-751.

48 Otte J.M., Mahjurian-Namari R., Brand S., et al. Probiotics regulate the expression of COX-2 in intestinal epithelial cells. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:103-113.

49 Wollowski I., Rechkemmer G., Pool-Zobel B.L. Protective role of probiotics and prebiotics in colon cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:451S-455S.

50 Mai V., Draganov P.V. Recent advances and remaining gaps in our knowledge of associations between gut microbiota and human health. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:81-85.

51 Blanarova C., Galovicova A., Petrasova D. Use of probiotics for prevention of radiation-induced diarrhea. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2009;110(2):98-104.

52 Giralt J., Regadera J.P., Verges R., et al. Effects of probiotic Lactobacillus casei DN-114 001 in prevention of radiation-induced diarrhea: results from multicenter, randomised, placebo-controlled nutritional trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(4):1213-1219.

53 Delia P., Sansotta G., Donato V., et al. Use of probiotics for prevention of radiation-induced diarrhea. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(6):912-915.

54 Kune G.A. Causes and control of colorectal cancer: model of cancer protection. Boston Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996.

55 Il’yasova D., Hodgson M.E., Martin C., et al. Tea consumption, apoptosis, and colorectal adenomas. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:439-443.

56 Clark L.C., Combs G.F.Jr., Turnbull B.W., et al. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin. A randomised controlled trial. Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group. JAMA. 1996;276:1957-1963.

57 Fernández-Bañares F., Cabré E., Esteve M., et al. Serum selenium and risk of large size colorectal adenomas in a geographical area with a low selenium status. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2103-2108.

58 Wallace K., Byers T., Morris J.S., et al. Prediagnostic serum selenium concentration and the risk of recurrent colorectal adenoma: a nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:464-467.

59 Kune G., Watson L. Colorectal cancer protective effects and the dietary micronutrients folate, methionine, vitamins B6, B12, C, E, selenium, and lycopene. Nutr Cancer. 2006;56:11-21.

60 Stone W.L., Papas A.M. Tocopherols and the etiology of colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1006-1014.

61 Jiang Q., Elson-Schwab I., Courtemanche C., et al. gamma-tocopherol and its major metabolite, in contrast to alpha-tocopherol, inhibit cyclooxygenase activity in macrophages and epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11494-11499.

62 Longnecker M.P., Martin-Moreno J.M., Knekt P., et al. Serum alpha-tocopherol concentration in relation to subsequent colorectal cancer: pooled data from five cohorts. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:430-435.

63 Wu K., Willett W.C., Chan J.M., et al. A prospective study on supplemental vitamin E intake and risk of colon cancer in women and men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1298-1304.

64 Murtaugh M.A., Ma K., Benson J., et al. Antioxidants, carotenoids, and risk of rectal cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:32-41.

65 Greenberg E.R., Baron J.A., Tosteson T.D., et al. A clinical trial of antioxidant vitamins to prevent colorectal adenoma. Polyp Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;33:141-147.

66 McKeown-Eyssen G., Holloway C., Jazmaji V., et al. A randomised trial of vitamins C and E in the prevention of recurrence of colorectal polyps. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4701-4705.

67 MacLennan R., Macrae F., Bain C., et al. Randomised trial of intake of fat, fibre, and beta carotene to prevent colorectal adenomas. Australian Polyp Prevention Project. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1760-1766.

68 DeCosse J.J., Miller H.H., Lesser M.L. Effect of wheat fibre and vitamins C and E on rectal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1290-1297.

69 Thangaraju M., Cresci G.A., Liu K., et al. GPR109A is a G-protein-coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2826-2832.

70 Zhang M.Z., Xu J., Yao B., et al. Inhibition of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II selectively blocks the tumor COX-2 pathway and suppresses colon carcinogenesis in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:876-885.

71 Stewart P.M., Prescott S.M. Can licorice lick colon cancer? J Clin Invest. 2009;119:760-763.