Chapter 2 Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair—Standard ![]()

1 Surgical Anatomy

The laparoscopic repair of ventral hernia borrows from the open technique espoused by Rives and Stoppa. It maintains the tenets of large mesh overlap with transabdominal fixation of the prosthetic. In a standard laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy, the biomaterial is placed intraabdominally in juxtaposition to the underlying viscera; therefore, a tissue-separating mesh is required. Traditionally, the hernia defect is bridged with mesh; however, some authors have described reapproximating the midline by closing the defect with transabdominal sutures.

The laparoscopic repair of ventral hernia borrows from the open technique espoused by Rives and Stoppa. It maintains the tenets of large mesh overlap with transabdominal fixation of the prosthetic. In a standard laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy, the biomaterial is placed intraabdominally in juxtaposition to the underlying viscera; therefore, a tissue-separating mesh is required. Traditionally, the hernia defect is bridged with mesh; however, some authors have described reapproximating the midline by closing the defect with transabdominal sutures. The amount of mesh overlap required for a durable ventral hernia repair is unknown. Based on Pascal’s principle, the intraabdominal pressure is evenly distributed over a large surface area of mesh. The initial experience with laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy reported a 3-cm overlap of mesh, but the current recommendation is at least a 4- to 5-cm margin. The amount of overlap depends on the diameter of the largest hernia defect and the thickness of the patient’s abdominal wall. One large defect deserves at least 5 cm, whereas numerous small defects (i.e., Swiss cheese hernia) may only require 4 cm of additional mesh.

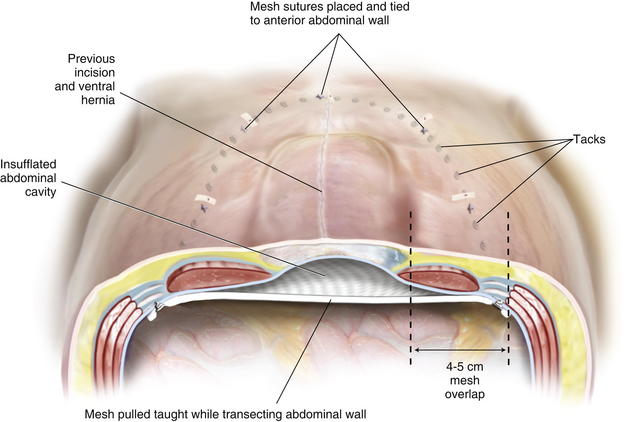

The amount of mesh overlap required for a durable ventral hernia repair is unknown. Based on Pascal’s principle, the intraabdominal pressure is evenly distributed over a large surface area of mesh. The initial experience with laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy reported a 3-cm overlap of mesh, but the current recommendation is at least a 4- to 5-cm margin. The amount of overlap depends on the diameter of the largest hernia defect and the thickness of the patient’s abdominal wall. One large defect deserves at least 5 cm, whereas numerous small defects (i.e., Swiss cheese hernia) may only require 4 cm of additional mesh. In a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, the mesh is placed in an insufflated abdominal cavity. Ideally, there is a slight degree of tension on the mesh at the completion of the repair. The mesh does not lie flush against the underside of the abdominal wall. Rather, it transects the abdominal space, so that when the abdominal cavity is desufflated, the mesh will not occupy the hernia sac (Fig. 2-1).

In a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, the mesh is placed in an insufflated abdominal cavity. Ideally, there is a slight degree of tension on the mesh at the completion of the repair. The mesh does not lie flush against the underside of the abdominal wall. Rather, it transects the abdominal space, so that when the abdominal cavity is desufflated, the mesh will not occupy the hernia sac (Fig. 2-1). There has been a lot of debate in the literature regarding the approach for ventral herniorrhaphy. Length of stay, postoperative pain, and operative times are essentially similar between the open and laparoscopic techniques in experienced hands. However, the laparoscopic technique consistently demonstrates significant reductions in wound and mesh infections. For this reason alone, the laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias should be the preferred approach when applicable.

There has been a lot of debate in the literature regarding the approach for ventral herniorrhaphy. Length of stay, postoperative pain, and operative times are essentially similar between the open and laparoscopic techniques in experienced hands. However, the laparoscopic technique consistently demonstrates significant reductions in wound and mesh infections. For this reason alone, the laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias should be the preferred approach when applicable.2 Preoperative Considerations

When considering who is a candidate for a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, certain patient characteristics must be considered. Contraindications include:

When considering who is a candidate for a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, certain patient characteristics must be considered. Contraindications include: Surgeon skill, particularly in the area of adhesiolysis, needs to be factored in when making the choice for a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Factors that portend a more difficult case requiring experience with the technique include:

Surgeon skill, particularly in the area of adhesiolysis, needs to be factored in when making the choice for a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Factors that portend a more difficult case requiring experience with the technique include: The preoperative consultation is critical in the patient undergoing laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy. The procedure is painful and not much different from an open repair in terms of postoperative discomfort. The real benefit of the laparoscopic approach is the well-documented reduction in wound- and mesh-related infectious complications. The likelihood of postoperative seroma formation should be discussed. The need for conversion to an open repair and the possibility of an enterotomy should be considered as well. The anticipated options if an enterotomy occurs should be explained to include not repairing the hernia defect at all.

The preoperative consultation is critical in the patient undergoing laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy. The procedure is painful and not much different from an open repair in terms of postoperative discomfort. The real benefit of the laparoscopic approach is the well-documented reduction in wound- and mesh-related infectious complications. The likelihood of postoperative seroma formation should be discussed. The need for conversion to an open repair and the possibility of an enterotomy should be considered as well. The anticipated options if an enterotomy occurs should be explained to include not repairing the hernia defect at all. Ventral hernias usually can be identified on physical exam, and no further work up is required. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdominal wall can be helpful in the patient who is morbidly obese, has a recurrent hernia (particularly with intraabdominal mesh), demonstrates a defect in proximity to a bony structure (i.e. suprapubic, subxiphoid, flank defects), or has concern for loss of domain.

Ventral hernias usually can be identified on physical exam, and no further work up is required. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdominal wall can be helpful in the patient who is morbidly obese, has a recurrent hernia (particularly with intraabdominal mesh), demonstrates a defect in proximity to a bony structure (i.e. suprapubic, subxiphoid, flank defects), or has concern for loss of domain. Patients who have previous failed attempts at repair can be difficult. The reasons for recurrence are usually not known, but certainly, efforts should be made not to repeat errors of the past. Every effort to obtain all operative reports that pertain to prior hernia repairs should be made. Before embarking on a recurrent defect, the surgeon should feel extremely confident with adhesiolysis and have a low threshold to convert to open. Patients who have had previous mesh infections that required removal of the prosthesis pose an extremely difficult challenge.

Patients who have previous failed attempts at repair can be difficult. The reasons for recurrence are usually not known, but certainly, efforts should be made not to repeat errors of the past. Every effort to obtain all operative reports that pertain to prior hernia repairs should be made. Before embarking on a recurrent defect, the surgeon should feel extremely confident with adhesiolysis and have a low threshold to convert to open. Patients who have had previous mesh infections that required removal of the prosthesis pose an extremely difficult challenge. The preoperative orders consist of antibiotic and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis. A first-generation cephalosporin is typically given, and the dose is adjusted for the morbidly obese. Because the ventral hernia patient is frequently obese, will be immobile postoperatively, and will experience increased intraabdominal pressure from pneumoperitoneum, sequential compression devices and subcutaneous heparin are employed preoperatively.

The preoperative orders consist of antibiotic and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis. A first-generation cephalosporin is typically given, and the dose is adjusted for the morbidly obese. Because the ventral hernia patient is frequently obese, will be immobile postoperatively, and will experience increased intraabdominal pressure from pneumoperitoneum, sequential compression devices and subcutaneous heparin are employed preoperatively.3 Operative Steps

1 Patient Positioning

For the majority of patients with defects in the midline, supine positioning with the arms tucked works well. The pressure points at the elbow and wrist should be padded (Fig. 2-2). For larger patients, the arm sleds may be required. In patients with defects off the midline or lumbar defects, a bump may be placed under the hip on the side of the hernia, or a true lateral position may be necessary with the aid of a bean bag.

For the majority of patients with defects in the midline, supine positioning with the arms tucked works well. The pressure points at the elbow and wrist should be padded (Fig. 2-2). For larger patients, the arm sleds may be required. In patients with defects off the midline or lumbar defects, a bump may be placed under the hip on the side of the hernia, or a true lateral position may be necessary with the aid of a bean bag. A Foley catheter is placed for bladder decompression and may be used to insufflate the bladder for identification in the repair of suprapubic defects. Gastric decompression is usually reserved for the patient requiring a difficult orotracheal intubation and may be achieved with orogastric tube decompression.

A Foley catheter is placed for bladder decompression and may be used to insufflate the bladder for identification in the repair of suprapubic defects. Gastric decompression is usually reserved for the patient requiring a difficult orotracheal intubation and may be achieved with orogastric tube decompression.2 Gaining Abdominal Access

Abdominal entry can be the most difficult step in the patient who has undergone multiple abdominal operations. Selecting the location for entry can be challenging because many of these patients have had numerous abdominal incisions. The upper quadrant at the tip of the eleventh rib is generally a safe place to gain access even in such cases. The side of entry should avoid previous incisions. For example, in the patient with an open cholecystectomy incision, the left upper quadrant should be chosen.

Abdominal entry can be the most difficult step in the patient who has undergone multiple abdominal operations. Selecting the location for entry can be challenging because many of these patients have had numerous abdominal incisions. The upper quadrant at the tip of the eleventh rib is generally a safe place to gain access even in such cases. The side of entry should avoid previous incisions. For example, in the patient with an open cholecystectomy incision, the left upper quadrant should be chosen. Several safe methods for initial access have been described. A cut-down technique works very well. Through a small incision in the upper quadrant, each layer of the abdominal wall is divided down to the peritoneum. The peritoneum can be sharply entered with a scalpel or bluntly penetrated with the finger to gain safe access to the abdominal cavity. The optical trocar can be used safely in the upper quadrant just below the rib line as well. Some surgeons prefer the Veress needle. The best technique is the one the surgeon is most comfortable and familiar with.

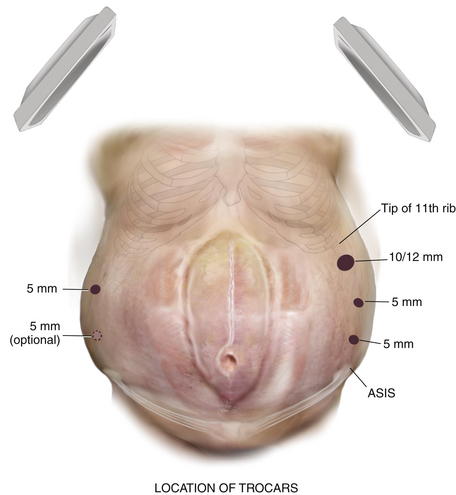

Several safe methods for initial access have been described. A cut-down technique works very well. Through a small incision in the upper quadrant, each layer of the abdominal wall is divided down to the peritoneum. The peritoneum can be sharply entered with a scalpel or bluntly penetrated with the finger to gain safe access to the abdominal cavity. The optical trocar can be used safely in the upper quadrant just below the rib line as well. Some surgeons prefer the Veress needle. The best technique is the one the surgeon is most comfortable and familiar with. Once initial entry into the abdominal cavity is achieved, at least one and preferably two additional trocars are placed laterally on the side of entry. Typically one can be placed above the initial site once pneumoperitoneum has been initiated, and an additional one can be inserted inferiorly with care not to be too close to the iliac crest. Two trocars are placed on the opposite side to provide additional viewing perspective for adhesiolysis and aid in retraction (Fig. 2-3).

Once initial entry into the abdominal cavity is achieved, at least one and preferably two additional trocars are placed laterally on the side of entry. Typically one can be placed above the initial site once pneumoperitoneum has been initiated, and an additional one can be inserted inferiorly with care not to be too close to the iliac crest. Two trocars are placed on the opposite side to provide additional viewing perspective for adhesiolysis and aid in retraction (Fig. 2-3).3 Adhesiolysis

The Achilles’ heel of the laparoscopic ventral hernia repair is the lysis of adhesions. This step can be the most time consuming and usually determines the length and complexity of the case.

The Achilles’ heel of the laparoscopic ventral hernia repair is the lysis of adhesions. This step can be the most time consuming and usually determines the length and complexity of the case. A 30-degree laparoscope is mandatory to adequately visualize the anterior abdominal wall. A 5-mm laparoscope provides more flexibility in moving the camera; however, if the visual clarity is poor, a 10-mm scope should be used.

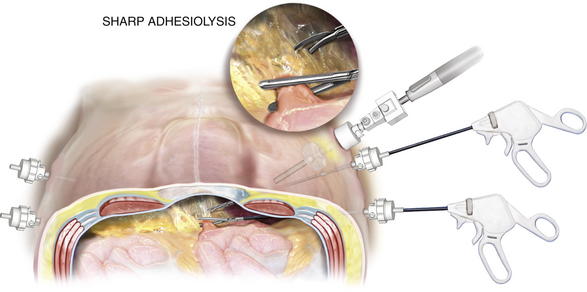

A 30-degree laparoscope is mandatory to adequately visualize the anterior abdominal wall. A 5-mm laparoscope provides more flexibility in moving the camera; however, if the visual clarity is poor, a 10-mm scope should be used. Energy sources should be avoided during adhesiolysis. Ultrasonic energy sources or bipolar coagulating shears should not be used. Thermal injuries seal at the time of dissection and may not be apparent for 3 to 5 days postoperatively. Sharp, cold, endoscopic scissor dissection should dominate the dissection. Blunt bowel graspers are crucial to aid in retraction of the viscera and can be used to provide gentle blunt dissection as well. Typically, during lysis of adhesions, the outer rind of adhesions may be sharply cut, giving way to a “cotton candy” appearance to the loose areolar tissue that comprises most of the adhesions (Fig. 2-4). Blunt dissection with gentle, short sweeps is very effective in this situation.

Energy sources should be avoided during adhesiolysis. Ultrasonic energy sources or bipolar coagulating shears should not be used. Thermal injuries seal at the time of dissection and may not be apparent for 3 to 5 days postoperatively. Sharp, cold, endoscopic scissor dissection should dominate the dissection. Blunt bowel graspers are crucial to aid in retraction of the viscera and can be used to provide gentle blunt dissection as well. Typically, during lysis of adhesions, the outer rind of adhesions may be sharply cut, giving way to a “cotton candy” appearance to the loose areolar tissue that comprises most of the adhesions (Fig. 2-4). Blunt dissection with gentle, short sweeps is very effective in this situation. External pressure applied on the abdominal wall by the assistant provides help during adhesiolysis. This move can be critical in the morbidly obese patient or in the situation where adhesions are up in the hernia sac. By bringing the dissection into the abdomen with pressure, visualization of the proper tissue planes is made possible.

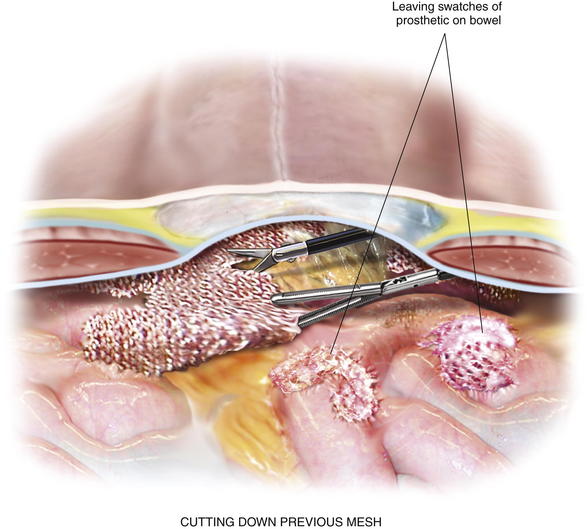

External pressure applied on the abdominal wall by the assistant provides help during adhesiolysis. This move can be critical in the morbidly obese patient or in the situation where adhesions are up in the hernia sac. By bringing the dissection into the abdomen with pressure, visualization of the proper tissue planes is made possible. Previous intraabdominal mesh can pose a real hazard to performing adhesiolysis. If the previous mesh contains a polypropylene or polyester component that becomes directly exposed to the bowel, there is not a plane of dissection. Attempts to mobilize the bowel off the adherent mesh will result in an enterotomy. In this situation, the mesh should be cut down off of the abdominal wall, leaving a swatch of prosthetic attached to the bowel (Fig. 2-5). Certainly, conversion to open is mandatory, if there is any concern for a bowel injury. Some cases of intense adhesion formation to the prosthetic may require a bowel resection.

Previous intraabdominal mesh can pose a real hazard to performing adhesiolysis. If the previous mesh contains a polypropylene or polyester component that becomes directly exposed to the bowel, there is not a plane of dissection. Attempts to mobilize the bowel off the adherent mesh will result in an enterotomy. In this situation, the mesh should be cut down off of the abdominal wall, leaving a swatch of prosthetic attached to the bowel (Fig. 2-5). Certainly, conversion to open is mandatory, if there is any concern for a bowel injury. Some cases of intense adhesion formation to the prosthetic may require a bowel resection. Bleeding during adhesiolysis can be very problematic. Slight oozing that typically occurs should be largely ignored. It rarely continues, and chasing it, especially with cautery, may lead to a bowel injury. If the area of oozing can be isolated from viscera, judicious monopolar cautery may be used. An oozing area of adipose tissue can be lifted away from underlying bowel and cauterized. Endoscopic hemoclip appliers can be extremely helpful in controlling bleeding in areas adjacent to bowel or where the location of bowel is unknown. Endoscopic pretied suture loops assist with bleeding sections of omentum or mesenteric fat. Be careful not to secure around a loop of bowel.

Bleeding during adhesiolysis can be very problematic. Slight oozing that typically occurs should be largely ignored. It rarely continues, and chasing it, especially with cautery, may lead to a bowel injury. If the area of oozing can be isolated from viscera, judicious monopolar cautery may be used. An oozing area of adipose tissue can be lifted away from underlying bowel and cauterized. Endoscopic hemoclip appliers can be extremely helpful in controlling bleeding in areas adjacent to bowel or where the location of bowel is unknown. Endoscopic pretied suture loops assist with bleeding sections of omentum or mesenteric fat. Be careful not to secure around a loop of bowel. Clearing the abdominal wall of all adhesions for the entire extent of the prior surgical incision is imperative. “Swiss cheese” defects not apparent preoperatively may become evident at this time. Extra time in this step is worthwhile to avoid the “early recurrence”—actually a defect missed at the initial repair.

Clearing the abdominal wall of all adhesions for the entire extent of the prior surgical incision is imperative. “Swiss cheese” defects not apparent preoperatively may become evident at this time. Extra time in this step is worthwhile to avoid the “early recurrence”—actually a defect missed at the initial repair. For defects above the umbilicus, the falciform ligament will have to be taken down to allow for flush placement of mesh against the abdominal wall. This move is best performed with electrocautery attached to the endoshears. The falciform is divided just below its insertion to the underside of the abdominal wall fascia.

For defects above the umbilicus, the falciform ligament will have to be taken down to allow for flush placement of mesh against the abdominal wall. This move is best performed with electrocautery attached to the endoshears. The falciform is divided just below its insertion to the underside of the abdominal wall fascia.4 Sizing the Hernia Defect

Measuring the defect is a critical step in the procedure. Many times, particularly following a lengthy adhesiolysis, this step may not be given much attention. A durable repair relies on adequate mesh overlap with proper placement, which are both directly a result of accurately measuring the defect.

Measuring the defect is a critical step in the procedure. Many times, particularly following a lengthy adhesiolysis, this step may not be given much attention. A durable repair relies on adequate mesh overlap with proper placement, which are both directly a result of accurately measuring the defect. The edges of the hernia defect are best delineated with the aid of 3.5-in, 20-gauge spinal needles placed at each edge of the defect. Insert the needle into the abdominal wall at a 90-degree angle to the floor, so the needle can emerge at the defect edge within the abdomen. Use a metric ruler to measure the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the defect between the needles. For multiple defects, place the needles to encompass all fascial defects, measuring them as one large defect.

The edges of the hernia defect are best delineated with the aid of 3.5-in, 20-gauge spinal needles placed at each edge of the defect. Insert the needle into the abdominal wall at a 90-degree angle to the floor, so the needle can emerge at the defect edge within the abdomen. Use a metric ruler to measure the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the defect between the needles. For multiple defects, place the needles to encompass all fascial defects, measuring them as one large defect. Three techniques have been described for measuring the defect: (1) externally with abdomen insufflated, (2) externally with abdomen desufflated, and (3) internally with abdomen insufflated. Because the mesh is being placed intracorporeally, it makes sense to make all measurements internally. The external measuring techniques overestimate the defect, which is more pronounced in larger defects and obese patients with thick anterior abdominal walls.

Three techniques have been described for measuring the defect: (1) externally with abdomen insufflated, (2) externally with abdomen desufflated, and (3) internally with abdomen insufflated. Because the mesh is being placed intracorporeally, it makes sense to make all measurements internally. The external measuring techniques overestimate the defect, which is more pronounced in larger defects and obese patients with thick anterior abdominal walls. Measure the defect internally under pneumoperitoneum. A plastic metric ruler is cut in half lengthwise and introduced via a 5-mm trocar. Two Maryland graspers manipulate the ruler and measure the defect between the spinal needles in the abdomen (Fig. 2-6). If the defect is longer than the ruler, insert another spinal needle along the axis of the defect within the length of the ruler. The sum of the two is the true measurement.

Measure the defect internally under pneumoperitoneum. A plastic metric ruler is cut in half lengthwise and introduced via a 5-mm trocar. Two Maryland graspers manipulate the ruler and measure the defect between the spinal needles in the abdomen (Fig. 2-6). If the defect is longer than the ruler, insert another spinal needle along the axis of the defect within the length of the ruler. The sum of the two is the true measurement.5 Mesh Introduction and Orientation

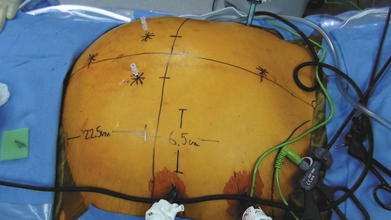

Not all hernia defects are perfectly circular, nor are they located exactly in the midline of the abdomen. In order to ensure that the mesh will be centered reliably over the defect every time, it is necessary to draw a grid of the x- and y-axes of the hernia defect on the external abdominal wall (Fig. 2-7).

Not all hernia defects are perfectly circular, nor are they located exactly in the midline of the abdomen. In order to ensure that the mesh will be centered reliably over the defect every time, it is necessary to draw a grid of the x- and y-axes of the hernia defect on the external abdominal wall (Fig. 2-7). With a ruler outside the abdomen, measure the distance halfway between the most superior and most inferior spinal needle. This determines the x-axis, the horizontal midpoint of the hernia. Half the horizontal distance between the lateral most spinal needles marks the y-axis, or the vertical midpoint. Draw both axes on the skin with a permanent marker to grid the abdomen and mark the center of the hernia defect. Once the mesh is brought into the abdomen, any attempt to retrieve one of the vertical or lateral cardinal sutures should be done along the corresponding x- or y-axis line. This will align the mesh over the defect and ensure the most accurate placement to achieve desired overlap (Fig. 2-8).

With a ruler outside the abdomen, measure the distance halfway between the most superior and most inferior spinal needle. This determines the x-axis, the horizontal midpoint of the hernia. Half the horizontal distance between the lateral most spinal needles marks the y-axis, or the vertical midpoint. Draw both axes on the skin with a permanent marker to grid the abdomen and mark the center of the hernia defect. Once the mesh is brought into the abdomen, any attempt to retrieve one of the vertical or lateral cardinal sutures should be done along the corresponding x- or y-axis line. This will align the mesh over the defect and ensure the most accurate placement to achieve desired overlap (Fig. 2-8). The type of mesh chosen for repair should have a favorable adhesion profile. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) has an excellent antiadhesion profile and works well for intraabdominal placement. Various absorbable barriers that coat polypropylene or polyester have been shown to provide reduction in adhesions as well. The infection profile of the biomaterial also should be considered.

The type of mesh chosen for repair should have a favorable adhesion profile. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) has an excellent antiadhesion profile and works well for intraabdominal placement. Various absorbable barriers that coat polypropylene or polyester have been shown to provide reduction in adhesions as well. The infection profile of the biomaterial also should be considered. Before introducing the mesh into the abdomen, simply fold the sheet in half vertically and horizontally. Mark the midpoint of each mesh edge. Then place the cardinal sutures at the 4 midpoints, taking a 1-cm bite in from the edge. PTFE suture works well because it has less memory and recoil. Tuck in the tails of the cardinal sutures and roll the mesh from both ends toward the middle like a scroll along the horizontal axis.

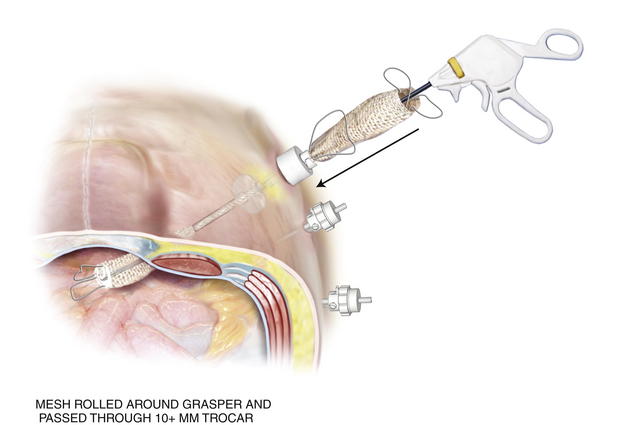

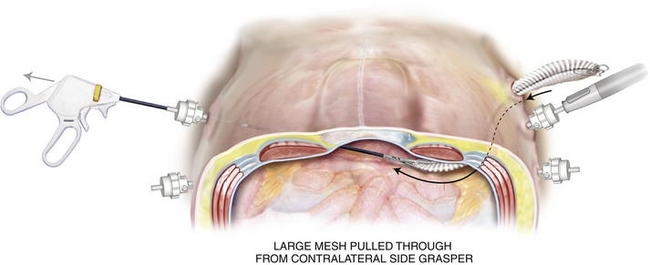

Before introducing the mesh into the abdomen, simply fold the sheet in half vertically and horizontally. Mark the midpoint of each mesh edge. Then place the cardinal sutures at the 4 midpoints, taking a 1-cm bite in from the edge. PTFE suture works well because it has less memory and recoil. Tuck in the tails of the cardinal sutures and roll the mesh from both ends toward the middle like a scroll along the horizontal axis. Once rolled, ePTFE mesh can be compressed and twisted to expunge air. Other tissue-separating meshes are soaked in saline and their slick texture makes them easier to introduce through a trocar. The rolled mesh may be passed directly through a 12-mm or 15-mm trocar (Fig. 2-9). Very large pieces of mesh can be dragged into the abdomen by passing a heavy grasper across the abdomen through a 5-mm trocar and out the contralateral side trocar. The cap of the trocar is removed, and the mesh is pulled into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 2-10). Every effort should be made to introduce the mesh through the trocar. This maneuver avoids contact with the patient’s skin.

Once rolled, ePTFE mesh can be compressed and twisted to expunge air. Other tissue-separating meshes are soaked in saline and their slick texture makes them easier to introduce through a trocar. The rolled mesh may be passed directly through a 12-mm or 15-mm trocar (Fig. 2-9). Very large pieces of mesh can be dragged into the abdomen by passing a heavy grasper across the abdomen through a 5-mm trocar and out the contralateral side trocar. The cap of the trocar is removed, and the mesh is pulled into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 2-10). Every effort should be made to introduce the mesh through the trocar. This maneuver avoids contact with the patient’s skin. Once inside the abdominal cavity, the mesh is unfurled. A grasper holds one end of the rolled mesh while the Maryland grasper uncoils the mesh (Fig. 2-11). It is important to maintain the proper orientation of the mesh. It may be helpful with larger pieces to mark a line across the horizontal axis of the mesh before insertion to ensure that the line runs from side-to-side.

Once inside the abdominal cavity, the mesh is unfurled. A grasper holds one end of the rolled mesh while the Maryland grasper uncoils the mesh (Fig. 2-11). It is important to maintain the proper orientation of the mesh. It may be helpful with larger pieces to mark a line across the horizontal axis of the mesh before insertion to ensure that the line runs from side-to-side.6 Securing the Mesh

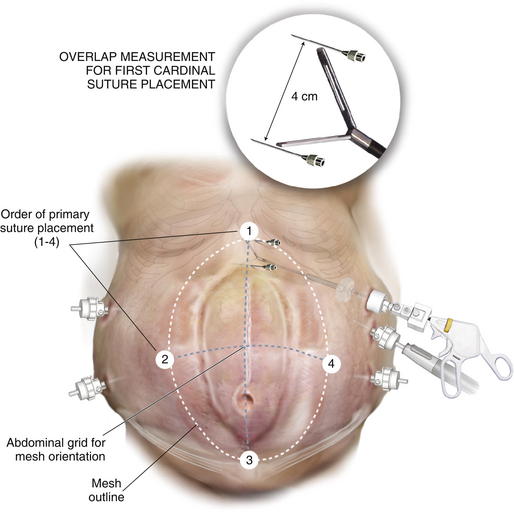

After unrolling the mesh, retrieve the cardinal suture at the vertical site where there is the least amount adjustment first. For example, if the defect is in the lower abdomen, the inferior suture should be placed initially to avoid having to move its location caudally towards the bladder when stretching the mesh. Likewise, if the defect approximates the xiphoid, the superior suture is placed first. Mark the edge of the defect at the site of cardinal suture placement with the spinal needle. An additional spinal needle is “walked out” the axis line for a distance of 5-cm to ensure overlap (Fig. 2-12). This measured spot is injected with local anesthesia, and a stab incision is made through which the suture passer is introduced. The suture passer retrieves each tail of the initial cardinal suture through the same small incision but at a different angle to achieve a separate fascial bite. Tag both suture tails but leave them untied.

After unrolling the mesh, retrieve the cardinal suture at the vertical site where there is the least amount adjustment first. For example, if the defect is in the lower abdomen, the inferior suture should be placed initially to avoid having to move its location caudally towards the bladder when stretching the mesh. Likewise, if the defect approximates the xiphoid, the superior suture is placed first. Mark the edge of the defect at the site of cardinal suture placement with the spinal needle. An additional spinal needle is “walked out” the axis line for a distance of 5-cm to ensure overlap (Fig. 2-12). This measured spot is injected with local anesthesia, and a stab incision is made through which the suture passer is introduced. The suture passer retrieves each tail of the initial cardinal suture through the same small incision but at a different angle to achieve a separate fascial bite. Tag both suture tails but leave them untied. Retrieve the lateral suture farthest from the camera. Measure a 5-cm overlap and mark the point for suture retrieval with an additional spinal needle placed along the x-axis. Bring this suture out of the abdomen, tag it, and leave it untied.

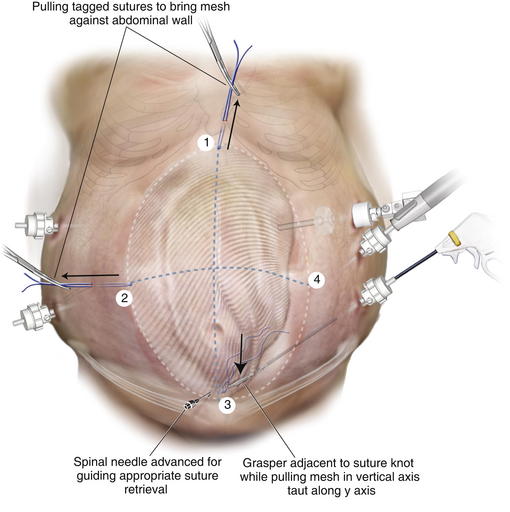

Retrieve the lateral suture farthest from the camera. Measure a 5-cm overlap and mark the point for suture retrieval with an additional spinal needle placed along the x-axis. Bring this suture out of the abdomen, tag it, and leave it untied. The assistant pulls on the tagged sutures to bring the mesh against the abdominal wall. The surgeon pulls the site in the vertical axis that is free along the y-axis. Advance a spinal needle through the abdominal wall along the axis. This guides where the suture will be retrieved, ensuring the mesh will be taut (Fig. 2-13). During this maneuver, avoid grasping the suture or the knot as this can weaken it. Measuring the overlap at this point is unnecessary because most prosthetic meshes stretch.

The assistant pulls on the tagged sutures to bring the mesh against the abdominal wall. The surgeon pulls the site in the vertical axis that is free along the y-axis. Advance a spinal needle through the abdominal wall along the axis. This guides where the suture will be retrieved, ensuring the mesh will be taut (Fig. 2-13). During this maneuver, avoid grasping the suture or the knot as this can weaken it. Measuring the overlap at this point is unnecessary because most prosthetic meshes stretch. The three cardinal sutures are pulled up to approximate the mesh to the underside of the abdominal wall. If the mesh appears to be centered over the defect and is taut, the sutures are secured.

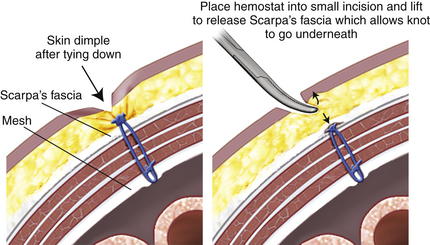

The three cardinal sutures are pulled up to approximate the mesh to the underside of the abdominal wall. If the mesh appears to be centered over the defect and is taut, the sutures are secured. The mesh at the final suture site is grasped adjacent to the knot and stretched along the x-axis. A spinal needle passed along the x-axis marks the spot for final cardinal suture retrieval, just as was done when placing the third suture. The suture passer retrieves the suture tails, and they are secured. Placing a hemostat into the small skin incision and lifting it allows the knot to fall below Scarpa fascia and not dimple the skin (Fig. 2-14).

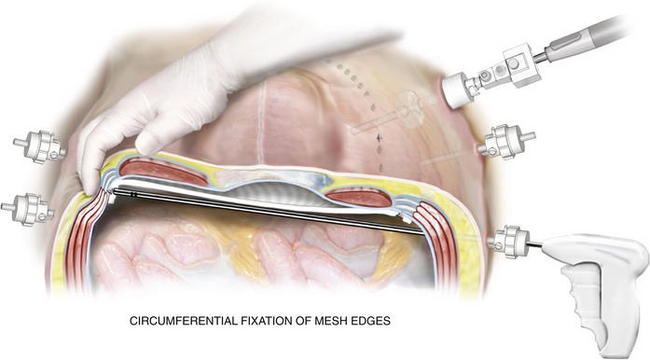

The mesh at the final suture site is grasped adjacent to the knot and stretched along the x-axis. A spinal needle passed along the x-axis marks the spot for final cardinal suture retrieval, just as was done when placing the third suture. The suture passer retrieves the suture tails, and they are secured. Placing a hemostat into the small skin incision and lifting it allows the knot to fall below Scarpa fascia and not dimple the skin (Fig. 2-14). Once the mesh is secured and overlap ensured, a tacking device is used to fixate the edges of the mesh circumferentially (Fig. 2-15). The purpose of the tacks is not to provide strength to the repair, but rather, to prevent bowel or mesenteric fat from creeping over the top of the mesh, exposing it to the ingrowth side. Fixation devices are both permanent and absorbable.

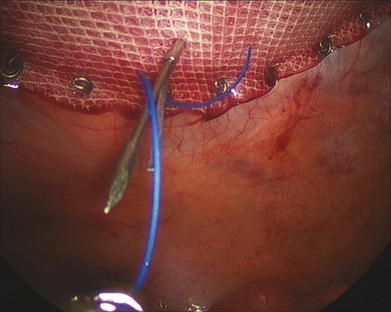

Once the mesh is secured and overlap ensured, a tacking device is used to fixate the edges of the mesh circumferentially (Fig. 2-15). The purpose of the tacks is not to provide strength to the repair, but rather, to prevent bowel or mesenteric fat from creeping over the top of the mesh, exposing it to the ingrowth side. Fixation devices are both permanent and absorbable. The strength of the repair is the transabdominal fixation that the permanent sutures provide. After tack fixation at the periphery of the mesh, additional permanent, monofilament sutures are placed every 5 to 7 cm around the circumference of the mesh (Fig. 2-16). Large defects require more frequent sutures; smaller, “Swiss cheese”–type defects may need fewer.

The strength of the repair is the transabdominal fixation that the permanent sutures provide. After tack fixation at the periphery of the mesh, additional permanent, monofilament sutures are placed every 5 to 7 cm around the circumference of the mesh (Fig. 2-16). Large defects require more frequent sutures; smaller, “Swiss cheese”–type defects may need fewer. Before completion of the case, one last inspection of the abdominal cavity is performed to rule out continued bleeding. The fascia at trocars larger than 5 mm should be closed with suture in this hernia-prone population. The skin at the trocar sites is closed with subcuticular stitches, followed by skin tapes or tissue cyanoacrylate.

Before completion of the case, one last inspection of the abdominal cavity is performed to rule out continued bleeding. The fascia at trocars larger than 5 mm should be closed with suture in this hernia-prone population. The skin at the trocar sites is closed with subcuticular stitches, followed by skin tapes or tissue cyanoacrylate.4 Postoperative Care

1 Perioperative Concerns

Appropriate pain management is vital in the immediate postoperative period. Apart from the 2- to 3-cm umbilical defect or trocar-site hernia, all patients undergoing laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy are admitted. Patient-controlled analgesia is very effective, especially in the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery. Scheduled intravenous ketorolac is a useful adjunct.

Appropriate pain management is vital in the immediate postoperative period. Apart from the 2- to 3-cm umbilical defect or trocar-site hernia, all patients undergoing laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy are admitted. Patient-controlled analgesia is very effective, especially in the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery. Scheduled intravenous ketorolac is a useful adjunct. The postoperative diet depends on the degree of adhesiolysis. Following procedures where there is a lengthy lysis of adhesions or when bowel is densely involved, the patient is kept NPO. The diet may be advanced when abdominal distention has resolved, and the patient is without nausea.

The postoperative diet depends on the degree of adhesiolysis. Following procedures where there is a lengthy lysis of adhesions or when bowel is densely involved, the patient is kept NPO. The diet may be advanced when abdominal distention has resolved, and the patient is without nausea. Hospitalization in the immediate postoperative period also allows the surgeon to monitor for any signs of missed enterotomy. There should always be an index of suspicion, particularly in difficult cases. Any unexplained tachycardia, leukocytosis, or persistent fever should be evaluated to rule out the presence of a bowel injury. Plane abdominal films or computed tomography can be used; however, if there is any concern, the patient should be returned to the operating room for diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy.

Hospitalization in the immediate postoperative period also allows the surgeon to monitor for any signs of missed enterotomy. There should always be an index of suspicion, particularly in difficult cases. Any unexplained tachycardia, leukocytosis, or persistent fever should be evaluated to rule out the presence of a bowel injury. Plane abdominal films or computed tomography can be used; however, if there is any concern, the patient should be returned to the operating room for diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy.2 Long-term Issues

Nearly all patients undergoing laparoscopic ventral hernia repair develop some degree of seroma at the previous hernia site. Patients should be educated about this possibility in the preoperative evaluation. Seromas rarely, if ever, require drainage or aspiration. The risk of contaminating the mesh with drainage should be weighed against the benefits of relieving the fluid. Indications for aspiration include failure to resolve after 6 months, significant patient discomfort, or pressure on the skin causing excoriation or necrosis.

Nearly all patients undergoing laparoscopic ventral hernia repair develop some degree of seroma at the previous hernia site. Patients should be educated about this possibility in the preoperative evaluation. Seromas rarely, if ever, require drainage or aspiration. The risk of contaminating the mesh with drainage should be weighed against the benefits of relieving the fluid. Indications for aspiration include failure to resolve after 6 months, significant patient discomfort, or pressure on the skin causing excoriation or necrosis. Persistent pain can be seen beyond 6 weeks following laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy. The pain almost always occurs at suture sites. Patients describe a burning or pulling sensation with movement. These suture sites can be injected with 30 mL of a mixture of lidocaine and bupivacaine; however, this treatment is rarely required.

Persistent pain can be seen beyond 6 weeks following laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy. The pain almost always occurs at suture sites. Patients describe a burning or pulling sensation with movement. These suture sites can be injected with 30 mL of a mixture of lidocaine and bupivacaine; however, this treatment is rarely required. Mesh infection is the bane of all hernia surgeons’ existence. Fortunately, the incidence of mesh infection is low; however, the consequences are grave. The management of mesh contamination is extensive and many times requires mesh removal. In patients that present with erythema of the abdominal wall or delayed abdominal pain over the mesh, CT imaging of the abdomen should be obtained. Fluid collection above or deep to the prosthetic that contains air is a mesh infection and is treated as such. The fluid may be aspirated and sent for gram stain and culture. The mesh should be removed if it has a component of ePTFE. Attempts to salvage the prosthetic should involve open drainage of the fluid collection with negative pressure vacuum therapy. This maneuver may be successful with lightweight polypropylene materials but is less so with polyester-based materials.

Mesh infection is the bane of all hernia surgeons’ existence. Fortunately, the incidence of mesh infection is low; however, the consequences are grave. The management of mesh contamination is extensive and many times requires mesh removal. In patients that present with erythema of the abdominal wall or delayed abdominal pain over the mesh, CT imaging of the abdomen should be obtained. Fluid collection above or deep to the prosthetic that contains air is a mesh infection and is treated as such. The fluid may be aspirated and sent for gram stain and culture. The mesh should be removed if it has a component of ePTFE. Attempts to salvage the prosthetic should involve open drainage of the fluid collection with negative pressure vacuum therapy. This maneuver may be successful with lightweight polypropylene materials but is less so with polyester-based materials. Follow-up in patients after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair has historically been very poor in the literature. The postoperative schedule should include appointments at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and yearly thereafter. Ideally, hernia patients should be examined at least up to 1 year for complications of seroma, persistent pain, and recurrence.

Follow-up in patients after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair has historically been very poor in the literature. The postoperative schedule should include appointments at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and yearly thereafter. Ideally, hernia patients should be examined at least up to 1 year for complications of seroma, persistent pain, and recurrence.5 Pearls/Pitfalls

Patients with poor skin quality should not be offered a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Many times the adhesions to the underlying fat or viscera provide blood supply to the compromised skin. Skin loss may result postoperatively, leaving the mesh exposed.

Patients with poor skin quality should not be offered a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Many times the adhesions to the underlying fat or viscera provide blood supply to the compromised skin. Skin loss may result postoperatively, leaving the mesh exposed. Leakage of gas at a trocar site or trocars that repeatedly fall out during a prolonged case can be quite frustrating. Replacing the leaking or loose trocar with a balloon-tipped trocar to reestablish a seal against the abdominal wall can save significant time and insufflation gas.

Leakage of gas at a trocar site or trocars that repeatedly fall out during a prolonged case can be quite frustrating. Replacing the leaking or loose trocar with a balloon-tipped trocar to reestablish a seal against the abdominal wall can save significant time and insufflation gas. For measuring large defects, an umbilical tape may be used internally. The tape is held at one of the needles and is stretched taut between the two points, marking the edge of the defect. The tape is brought out through the trocar and measured.

For measuring large defects, an umbilical tape may be used internally. The tape is held at one of the needles and is stretched taut between the two points, marking the edge of the defect. The tape is brought out through the trocar and measured. One drawback to the laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias has been the inability to reapproximate the midline and reestablish a functional abdominal wall. Patient expectations should clearly be discussed preoperatively. In this instance, an open retrorectus mesh repair may be more beneficial. The ventral defect may be closed during a laparoscopic repair with transabdominal sutures. This technique is usually reserved for defects measuring less than 10 cm in width.

One drawback to the laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias has been the inability to reapproximate the midline and reestablish a functional abdominal wall. Patient expectations should clearly be discussed preoperatively. In this instance, an open retrorectus mesh repair may be more beneficial. The ventral defect may be closed during a laparoscopic repair with transabdominal sutures. This technique is usually reserved for defects measuring less than 10 cm in width. Be cautious of the patient with a history of previous mesh infection! If the prosthetic was contaminated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, an open repair reinforced with a biologic or bioresorbable graft may be preferred. This approach may require a component separation to gain midline closure of the fascia.

Be cautious of the patient with a history of previous mesh infection! If the prosthetic was contaminated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, an open repair reinforced with a biologic or bioresorbable graft may be preferred. This approach may require a component separation to gain midline closure of the fascia.Carbonell A.M., Harold K.L., Mahmutovic A.J., et al. Local injection for the treatment of suture site pain after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Am Surg. 2003;69:688-691.

Cobb W.S., Kercher K.W., Heniford B.T. Laparoscopic repair of incisional hernia. Surg Clin N Am. 2005;85(1):91-103.

Heniford B.T., Park A., Ramshaw B.J., Voeller G. Laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias: nine years’ experience with 850 consecutive hernias. Ann Surg. 2003;238:391-399.

Novitsky Y.W., Paton B.L., Heniford B.T. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. In: Koltun W., editor. Operative techniques in general surgery: techniques of laparoscopic hernia repair. New York: Elsevier, Inc; 2006:4-9. Chapter 3

Rosen M.J. Polyester-based mesh for ventral hernia repair: is it safe? Am J Surg. 2009;197:353-359.

Stoppa R.E. The treatment of complicated groin and incisional hernias. World J Surg. 1989;13:545-554.