Chapter 4 Laparoscopic Repair of Parastomal Hernias ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy

1 Types of Parastomal Hernias

Parastomal hernia has been anatomically classified into four subtypes: (Fig. 4-1)

2 Preoperative Considerations

The life expectancy of the patient and any predisposing factors, such as malignancy and obesity, should influence the decision to proceed with surgery.

The life expectancy of the patient and any predisposing factors, such as malignancy and obesity, should influence the decision to proceed with surgery. Accurate diagnosis and assessment of the anatomy of the hernia are essential. This is done with clinical examination, or more accurately, with a computed tomography (CT) scan.

Accurate diagnosis and assessment of the anatomy of the hernia are essential. This is done with clinical examination, or more accurately, with a computed tomography (CT) scan. CT scan is useful to delineate parastomal defects, any associated incisional hernia, and the content of the hernia (Fig. 4-2).

CT scan is useful to delineate parastomal defects, any associated incisional hernia, and the content of the hernia (Fig. 4-2). A preoperative bowel preparation may diminish the risk of infection if there is a colonic injury during laparoscopy.

A preoperative bowel preparation may diminish the risk of infection if there is a colonic injury during laparoscopy. A large Foley catheter may be inserted into the stoma to facilitate location of the bowel intraoperatively.

A large Foley catheter may be inserted into the stoma to facilitate location of the bowel intraoperatively.3 Operative Steps

There are two techniques for laparoscopic repairs of parastomal hernias: the keyhole and the Sugarbaker techniques. Keyhole technique may be associated with bowel herniation between the mesh hole and the stoma loop. We have developed a technique that closes the gap between the mesh and the stoma loop and facilitates intracorporeal mesh manipulations (Scroll technique) during keyhole repairs. The Sugarbaker technique avoids the risk of herniation through the keyhole, but it does create an acute angle as the bowel exits the mesh and can cause obstruction (see Fig. 4-11). Meticulous attention to the details of mesh fixation and placement can limit these complications.

1 Laparoscopic Parastomal Hernia Repair Technique: The Scroll Technique

1 Laparoscopic Parastomal Hernia Repair Technique: The Scroll Technique

Operating Room Setup (Fig. 4-3)

Operating Room Setup (Fig. 4-3)

Trocar Placement (Fig. 4-4)

Trocar Placement (Fig. 4-4)

Lysis of Adhesions

Lysis of Adhesions

Lysis of adhesions is the most challenging part of this procedure; this is performed using sharp or blunt dissection as close as possible to the anterior abdominal wall.

Lysis of adhesions is the most challenging part of this procedure; this is performed using sharp or blunt dissection as close as possible to the anterior abdominal wall. An energy source can be used only after ensuring no bowel is nearby to avoid lateral thermal injury.

An energy source can be used only after ensuring no bowel is nearby to avoid lateral thermal injury. One of the most challenging aspects of this type of laparoscopic repair is that one loop of bowel must remain on the abdominal wall. This can be difficult to differentiate with laparoscopic visualization. As mentioned, a Foley catheter, or occasionally, intraoperative endoscopy can guide the surgeon.

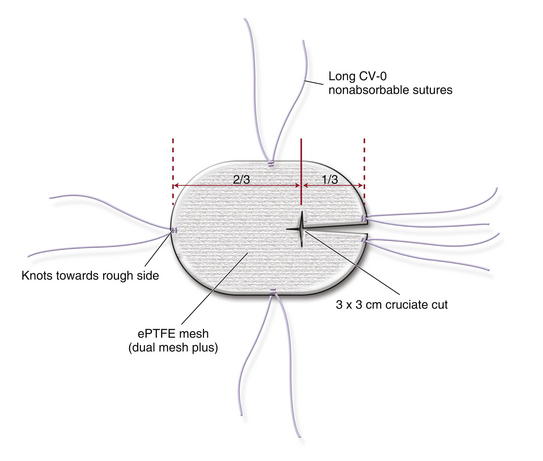

One of the most challenging aspects of this type of laparoscopic repair is that one loop of bowel must remain on the abdominal wall. This can be difficult to differentiate with laparoscopic visualization. As mentioned, a Foley catheter, or occasionally, intraoperative endoscopy can guide the surgeon. Mesh Choice and Preparation (Figs. 4-5 and 4-6)

Mesh Choice and Preparation (Figs. 4-5 and 4-6)

Keyhole Technique

Keyhole Technique

The mesh is fashioned by creating a 3 × 3 cm cruciate cut at the junction of two thirds and one third of the mesh (see Fig. 4-5).

The mesh is fashioned by creating a 3 × 3 cm cruciate cut at the junction of two thirds and one third of the mesh (see Fig. 4-5). Mesh Fixation

Mesh Fixation

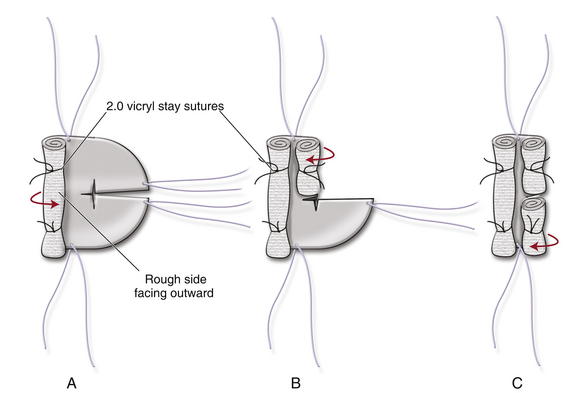

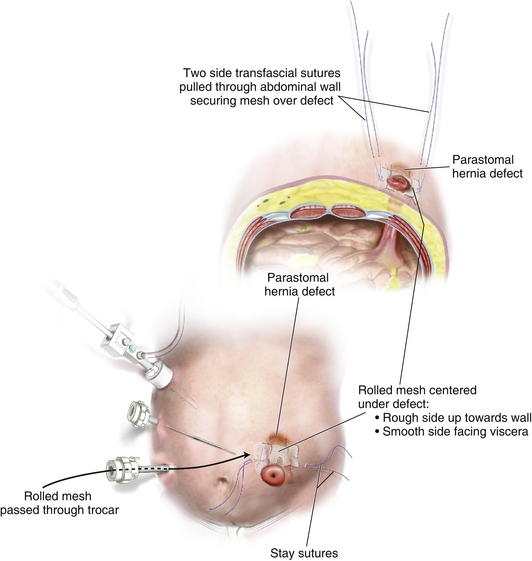

Once the mesh is inside the abdominal cavity, the two transfascial sutures at the sides of the mesh are pulled through the abdominal wall with the suture passer. This will bring the rolled mesh adherent to the abdominal wall, centering it over the defect with the mesh split toward the colostomy side (Fig. 4-7).

Once the mesh is inside the abdominal cavity, the two transfascial sutures at the sides of the mesh are pulled through the abdominal wall with the suture passer. This will bring the rolled mesh adherent to the abdominal wall, centering it over the defect with the mesh split toward the colostomy side (Fig. 4-7). Care must be taken that the rough surface faces the anterior abdominal wall and the smooth surface faces the viscera.

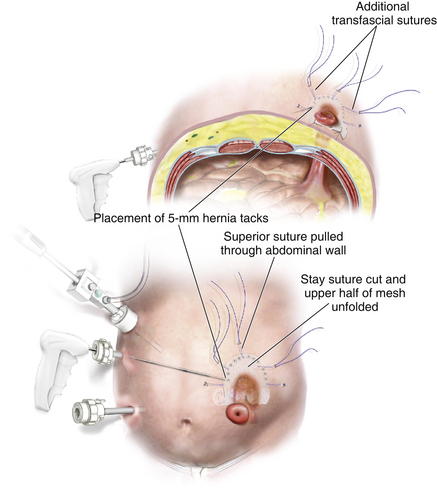

Care must be taken that the rough surface faces the anterior abdominal wall and the smooth surface faces the viscera. The transabdominal sutures are tied. The Vicryl stay suture is cut, and the upper half of the mesh is unfolded (Fig. 4-8).

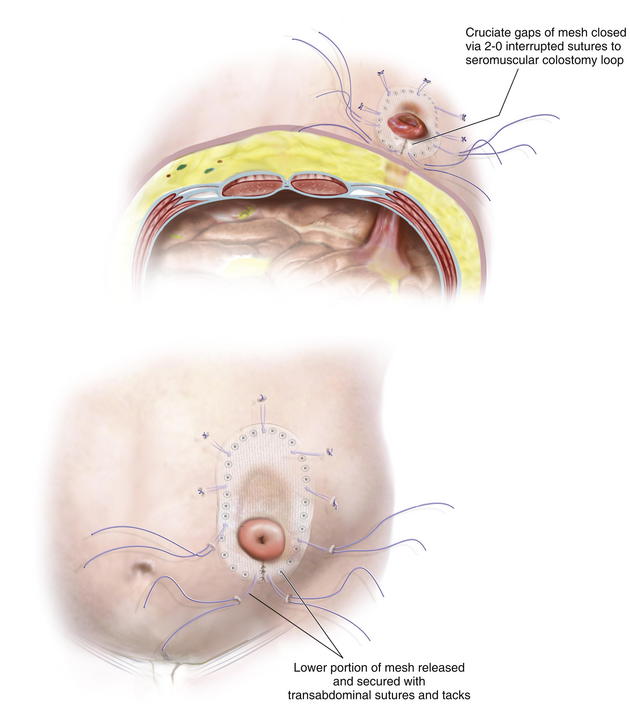

The transabdominal sutures are tied. The Vicryl stay suture is cut, and the upper half of the mesh is unfolded (Fig. 4-8). Next, 5-mm hernia tacks are placed circumferentially, 1 cm from the edge of the mesh and 1 to 2 cm apart.

Next, 5-mm hernia tacks are placed circumferentially, 1 cm from the edge of the mesh and 1 to 2 cm apart. The same procedure is repeated on the other half of the mesh (Fig. 4-9), cutting the Vicryl stay suture and spreading each part of the lower portion of the mesh individually. The mesh portions are fixed using transabdominal sutures and 5-mm hernia tacks.

The same procedure is repeated on the other half of the mesh (Fig. 4-9), cutting the Vicryl stay suture and spreading each part of the lower portion of the mesh individually. The mesh portions are fixed using transabdominal sutures and 5-mm hernia tacks. After the mesh is secured properly to the abdominal wall, the gaps between the colostomy and the cruciate defect in the mesh are closed with interrupted 2-0 nonabsorbable sutures securing the mesh to the seromuscular layer of the colostomy loop.

After the mesh is secured properly to the abdominal wall, the gaps between the colostomy and the cruciate defect in the mesh are closed with interrupted 2-0 nonabsorbable sutures securing the mesh to the seromuscular layer of the colostomy loop. Additional transfascial sutures are placed circumferentially at 5-cm intervals to augment long-term stability.

Additional transfascial sutures are placed circumferentially at 5-cm intervals to augment long-term stability. 2 Laparoscopic Sugarbaker Technique (Fig. 4-11)

2 Laparoscopic Sugarbaker Technique (Fig. 4-11)

The laparoscopic Sugarbaker technique involves placing a flat sheet of mesh on the abdominal wall and lateralizing the stoma’s loop of bowel. In order to perform this procedure, the bowel must have sufficient mobilization to allow it to be displaced laterally without excessive kinking. Occasionally, ileal conduit hernias cannot be lateralized because of the posterior fixation of the ureters.

The laparoscopic Sugarbaker technique involves placing a flat sheet of mesh on the abdominal wall and lateralizing the stoma’s loop of bowel. In order to perform this procedure, the bowel must have sufficient mobilization to allow it to be displaced laterally without excessive kinking. Occasionally, ileal conduit hernias cannot be lateralized because of the posterior fixation of the ureters. Once the defect is measured, an appropriately sized piece of mesh is designed to provide at least 5 cm of overlap.

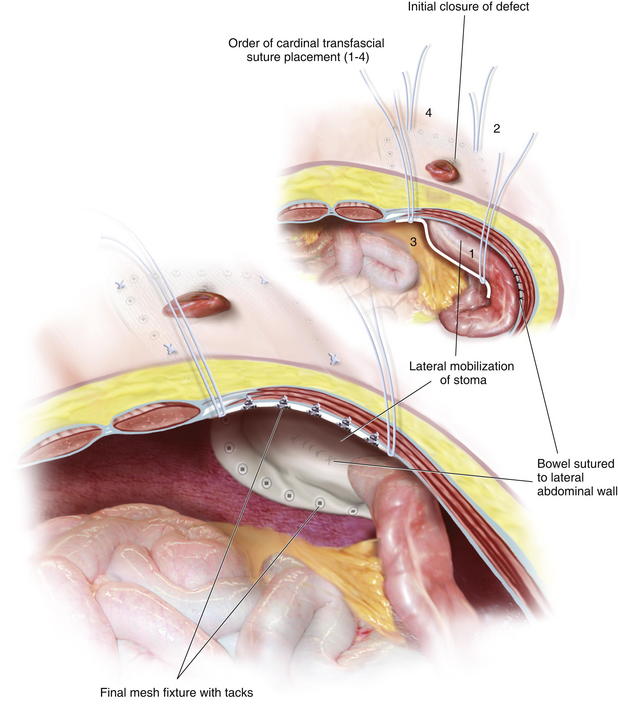

Once the defect is measured, an appropriately sized piece of mesh is designed to provide at least 5 cm of overlap. We typically suture the bowel to the lateral abdominal wall before bringing in the mesh. This allows the surgeon to see the angle of the bowel before being obscured by the prosthesis. Additionally it confirms that there is not too much tension on the bowel as it makes this angle and avoids the mesh acting as a sling on the bowel wall that is not secured to the abdominal wall.

We typically suture the bowel to the lateral abdominal wall before bringing in the mesh. This allows the surgeon to see the angle of the bowel before being obscured by the prosthesis. Additionally it confirms that there is not too much tension on the bowel as it makes this angle and avoids the mesh acting as a sling on the bowel wall that is not secured to the abdominal wall. Placing the four cardinal transfascial sutures at each corner of the mesh aids in mesh positioning (see Fig. 4-11).

Placing the four cardinal transfascial sutures at each corner of the mesh aids in mesh positioning (see Fig. 4-11). The inferior lateral suture is retrieved first, after 5 cm of overlap is measured. Given the typical lower lateral location of most stomas on the abdominal wall, it is important to retrieve this suture first, since you will often be limited by the major neurovascular structures of the pelvis.

The inferior lateral suture is retrieved first, after 5 cm of overlap is measured. Given the typical lower lateral location of most stomas on the abdominal wall, it is important to retrieve this suture first, since you will often be limited by the major neurovascular structures of the pelvis. The superior lateral suture is subsequently retrieved. These sutures are then tightened on the abdominal wall. The surgeon can then see over the mesh and confirm that the bowel is not being too acutely angled as it exits the mesh.

The superior lateral suture is subsequently retrieved. These sutures are then tightened on the abdominal wall. The surgeon can then see over the mesh and confirm that the bowel is not being too acutely angled as it exits the mesh. A tacking device is then used to secure the mesh to the anterior abdominal wall every 1 cm. When placing tacks next to the stoma site, great care must be used to avoid injuring or obstructing the lumen. There is no exact measurement to allow the surgeon to confirm appropriate mesh and bowel placement, and great care should be used. Because the mesh is placed during full insufflation, it is likely that as the abdomen is desufflated the mesh will loosen a bit.

A tacking device is then used to secure the mesh to the anterior abdominal wall every 1 cm. When placing tacks next to the stoma site, great care must be used to avoid injuring or obstructing the lumen. There is no exact measurement to allow the surgeon to confirm appropriate mesh and bowel placement, and great care should be used. Because the mesh is placed during full insufflation, it is likely that as the abdomen is desufflated the mesh will loosen a bit.4 Postoperative Care

5 Pearls/Pitfalls

When dealing with parastomal hernias, we need to repair the hernia while maintaining the defect in the abdominal wall for the colostomy loop to pass without obstruction.

When dealing with parastomal hernias, we need to repair the hernia while maintaining the defect in the abdominal wall for the colostomy loop to pass without obstruction. Scroll technique facilitates intracorporeal mesh manipulation, maintains precise orientation of the mesh in relation to the hernia defect, and allows secure fixation of the mesh to the anterior abdominal wall.

Scroll technique facilitates intracorporeal mesh manipulation, maintains precise orientation of the mesh in relation to the hernia defect, and allows secure fixation of the mesh to the anterior abdominal wall. The rolled mesh is placed through the 12-mm Hasson trocar into the abdominal cavity; this will avoid mesh contamination from the skin.

The rolled mesh is placed through the 12-mm Hasson trocar into the abdominal cavity; this will avoid mesh contamination from the skin. The fundamental components of a sound hernia repair of wide mesh overlap of the defect and transabdominal sutures are used.

The fundamental components of a sound hernia repair of wide mesh overlap of the defect and transabdominal sutures are used. Full-thickness nonabsorbable sutures are crucial for long-term stability of the mesh to the abdominal wall while the 5-mm tacks close the gaps between the abdominal wall and the mesh, thereby preventing incarceration of a loop of bowel between the mesh and the abdominal wall.

Full-thickness nonabsorbable sutures are crucial for long-term stability of the mesh to the abdominal wall while the 5-mm tacks close the gaps between the abdominal wall and the mesh, thereby preventing incarceration of a loop of bowel between the mesh and the abdominal wall. The laparoscopic approach visualizes the entire abdominal wall, thus detecting any impalpable hernia defect that also may be repaired at the same time.

The laparoscopic approach visualizes the entire abdominal wall, thus detecting any impalpable hernia defect that also may be repaired at the same time. Large midline defects in addition to parastomal hernias can be very challenging to simultaneously repair, and occasionally, an open approach or the use of two meshes laparoscopically is warranted.

Large midline defects in addition to parastomal hernias can be very challenging to simultaneously repair, and occasionally, an open approach or the use of two meshes laparoscopically is warranted.Berger D., Bientzle M. Laparoscopic repair of parastomal hernias: a single surgeon’s experience in 66 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007 Oct;50(10):1668-1673.

Craft R.O., Huguet K.L., McLemore E.C., Harold K.L. Laparoscopic parastomal hernia repair. Hernia. 2008 Apr;12(2):137-140.

Hansson B.M., Bleichrodt R.P., de Hingh I.H. Laparoscopic parastomal hernia repair using a keyhole technique results in a high recurrence rate. Surg Endosc. 2009 Jul;23(7):1456-1459.

Muysoms E.E., Hauters P.J., Van Nieuwenhove Y., Huten N., Claeys D.A. Laparoscopic repair of parastomal hernias: a multi-centre retrospective review and shift in technique. Acta Chir Belg. 2008 Jul-Aug;108(4):400-404.

Muysoms F. Laparoscopic repair of parastomal hernias with a modified Sugarbaker technique. Acta Chir Belg. 2007 Jul-Aug;107(4):476-480.

Saber A.A., Rao A.J., Rao C.A., Elgamal M.H. Simplified laparoscopic parastomal hernia repair: the scroll technique. Am J Surg. 2008 Sep;196(3):16-18.