Chapter 3 Laparoscopic Repair of Atypical Hernias

Suprapubic, Subxiphoid, and Lumbar ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy

The laparoscopic repair of incisional hernias that occurs at the extremes of the abdomen either superiorly, inferiorly, or laterally can present many unique challenges to the surgeon. These hernias are often near major neurovascular or bony structures, making adequate overlap of mesh and fixation difficult. Typical locations for these types of hernias include the subxiphoid, suprapubic, or lumbar areas. These atypical hernias can often be approached and repaired laparoscopically with careful preoperative planning.

The laparoscopic repair of incisional hernias that occurs at the extremes of the abdomen either superiorly, inferiorly, or laterally can present many unique challenges to the surgeon. These hernias are often near major neurovascular or bony structures, making adequate overlap of mesh and fixation difficult. Typical locations for these types of hernias include the subxiphoid, suprapubic, or lumbar areas. These atypical hernias can often be approached and repaired laparoscopically with careful preoperative planning.1 Suprapubic Hernia

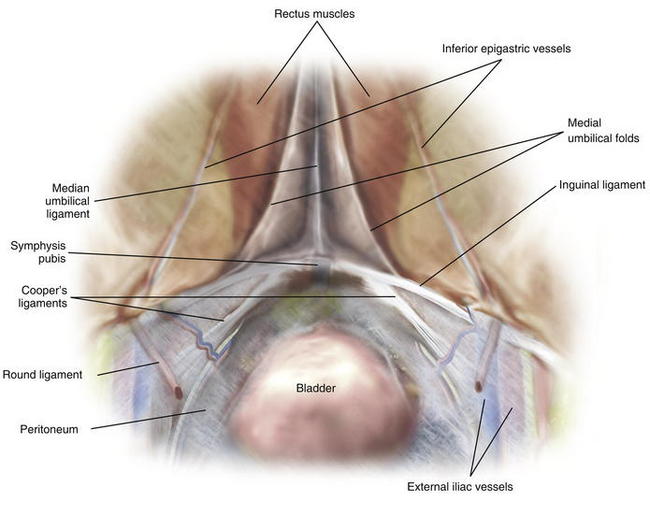

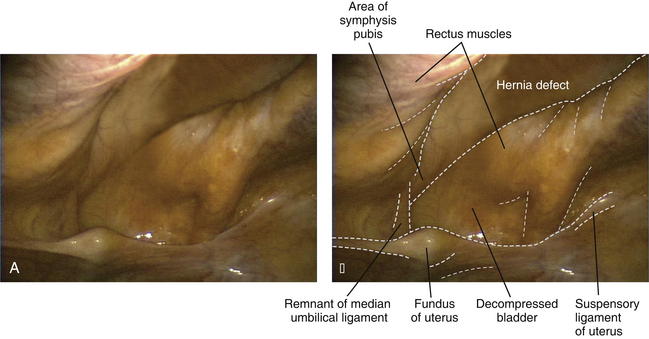

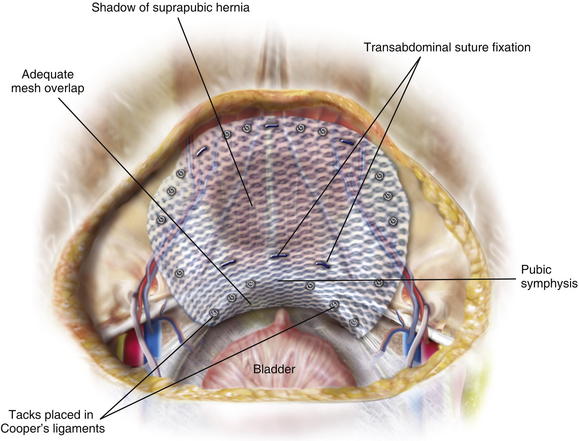

Correct and timely identification of the key structures in the lower anterior abdominal wall is critical for the safe laparoscopic repair of suprapubic hernias (Fig. 3-1). A careful preperitoneal dissection provides the needed landmarks for appropriate fixation to lessen the chance of postoperative recurrence.

Correct and timely identification of the key structures in the lower anterior abdominal wall is critical for the safe laparoscopic repair of suprapubic hernias (Fig. 3-1). A careful preperitoneal dissection provides the needed landmarks for appropriate fixation to lessen the chance of postoperative recurrence.2 Subxiphoid Hernia

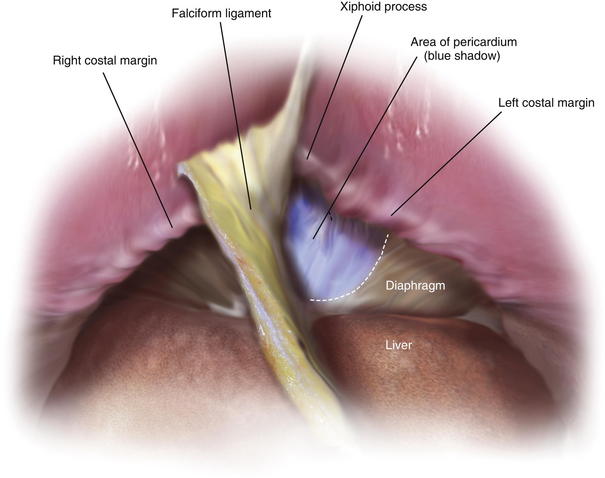

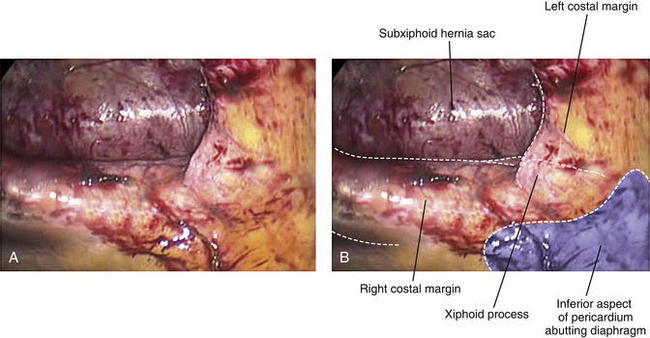

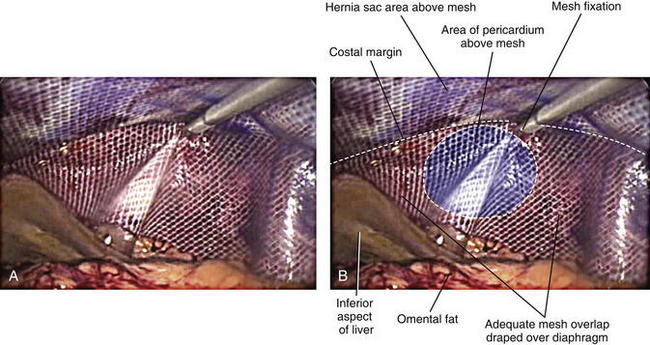

Identification of the costal margins and xiphoid process provide the laparoscopic bounds of transabdominal fixation for repair of subxiphoid hernias (Fig. 3-2). Generous overlap of the mesh over the diaphragm helps provide adequate coverage of the fascial defect in lieu of superior fixation.

Identification of the costal margins and xiphoid process provide the laparoscopic bounds of transabdominal fixation for repair of subxiphoid hernias (Fig. 3-2). Generous overlap of the mesh over the diaphragm helps provide adequate coverage of the fascial defect in lieu of superior fixation.3 Lumbar Hernia

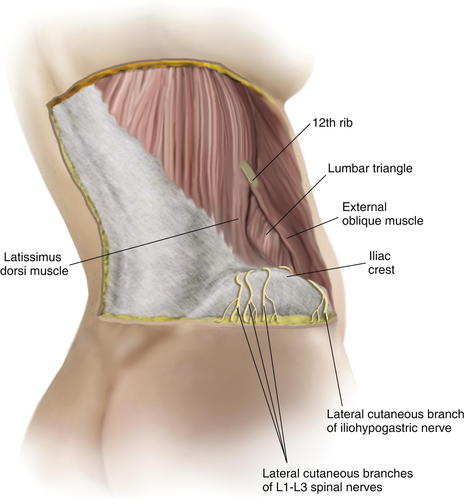

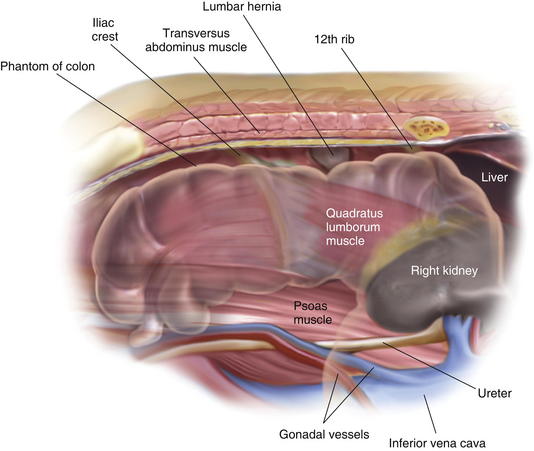

The lumbar triangle is defined superiorly and laterally by the latissimus dorsi muscle, medially by the external oblique muscle, and inferiorly by the iliac crest (Fig. 3-3). Weakness of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis musculature within the lumbar triangle leads to hernia formation (Fig. 3-4). An anterior abdominal approach can be used for laparoscopic repair, with proper patient positioning used to strategically expose the lumbar triangle.

The lumbar triangle is defined superiorly and laterally by the latissimus dorsi muscle, medially by the external oblique muscle, and inferiorly by the iliac crest (Fig. 3-3). Weakness of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis musculature within the lumbar triangle leads to hernia formation (Fig. 3-4). An anterior abdominal approach can be used for laparoscopic repair, with proper patient positioning used to strategically expose the lumbar triangle.2 Preoperative Considerations

1 Laparoscopic or Open Approach?

The decision to proceed between a laparoscopic or open approach to atypical hernias rests on the surgeon’s ability to estimate adequate coverage of the defect via laparoscopic approach and the candidacy of the patient for creation of a more physiologic repair via an open abdominal wall reconstruction. Relatively large fascial defects within 4 cm of the iliac crest are difficult to approach laparoscopically. Younger, active patients with sizable subxiphoid hernias may benefit from an open retrorectus or preperitoneal repair when dissection above the costal margins can be performed along with rectus medialization. Conversely, patients with smaller defects and those who may not tolerate an extensive abdominal wall reconstruction may benefit from a laparoscopic approach.

The decision to proceed between a laparoscopic or open approach to atypical hernias rests on the surgeon’s ability to estimate adequate coverage of the defect via laparoscopic approach and the candidacy of the patient for creation of a more physiologic repair via an open abdominal wall reconstruction. Relatively large fascial defects within 4 cm of the iliac crest are difficult to approach laparoscopically. Younger, active patients with sizable subxiphoid hernias may benefit from an open retrorectus or preperitoneal repair when dissection above the costal margins can be performed along with rectus medialization. Conversely, patients with smaller defects and those who may not tolerate an extensive abdominal wall reconstruction may benefit from a laparoscopic approach.2 Patient Positioning and Trocar Placement

For laparoscopic suprapubic and subxiphoid hernia repairs, the patient is placed in the supine position, with arms tucked and carefully padded. Laparoscopic lumbar hernia repair often requires elevation of the ipsilateral side for posterior transabdominal fixation (Fig. 3-5). Usual trocar placement for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair should suffice for initial approach and lysis of adhesions (see Chapter 2, Fig. 2-3). These parts are placed more medially than usual on the contralateral side of the hernia defect. Access to the suprapubic region and myopectineal orifice is facilitated through three trocars at the level of the umbilicus; two are placed just lateral to the linea semilunaris, and one is placed at the umbilicus.

For laparoscopic suprapubic and subxiphoid hernia repairs, the patient is placed in the supine position, with arms tucked and carefully padded. Laparoscopic lumbar hernia repair often requires elevation of the ipsilateral side for posterior transabdominal fixation (Fig. 3-5). Usual trocar placement for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair should suffice for initial approach and lysis of adhesions (see Chapter 2, Fig. 2-3). These parts are placed more medially than usual on the contralateral side of the hernia defect. Access to the suprapubic region and myopectineal orifice is facilitated through three trocars at the level of the umbilicus; two are placed just lateral to the linea semilunaris, and one is placed at the umbilicus.3 Operative Steps

1 Suprapubic

1 Suprapubic

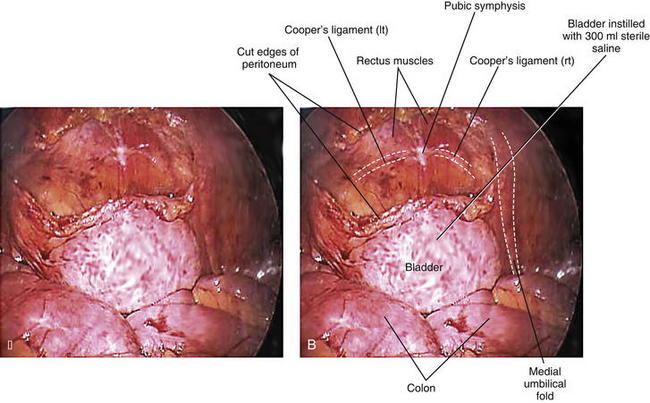

After complete adhesiolysis and delineation of the hernia defect (Fig. 3-6), the relationship of the inferior extent of the hernia and the bladder is defined. The three-way Foley catheter is clamped and 300 mL of sterile normal saline is instilled into the bladder, distending it for ease in identification (Fig. 3-7).

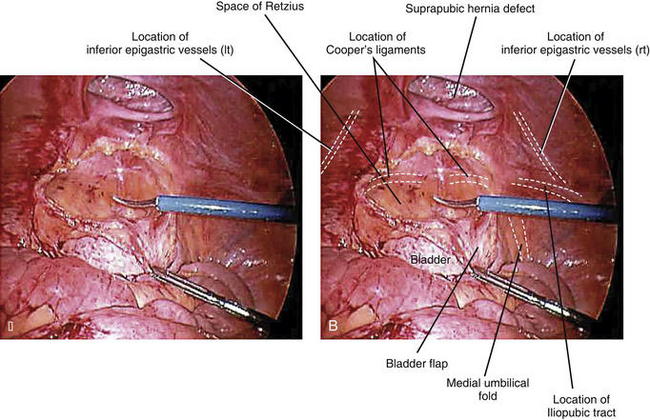

After complete adhesiolysis and delineation of the hernia defect (Fig. 3-6), the relationship of the inferior extent of the hernia and the bladder is defined. The three-way Foley catheter is clamped and 300 mL of sterile normal saline is instilled into the bladder, distending it for ease in identification (Fig. 3-7). The inferior epigastric vessels are located on the opposite side of the operating surgeon and the preperitoneal space entered, mobilizing the flap medially. A preperitoneal tunnel is developed to identify Cooper’s ligament. The preperitoneal space lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels is developed toward the iliopubic tract if needed. The peritoneum is then swept away from the inferior epigastric vessels, fully mobilizing the preperitoneal space on this side. A similar dissection is performed to expose the contralateral preperitoneal space. The bladder is then mobilized off the midline using electrosurgical current. The dissection is carried down to the pubis. Cooper’s ligament is identified bilaterally, and the bladder is mobilized inferiorly into the space of Retzius. If the hernia abuts the pubis, it is important to mobilize the bladder sufficiently to allow several centimeters of mesh to be tucked under the pubis (Fig. 3-8).

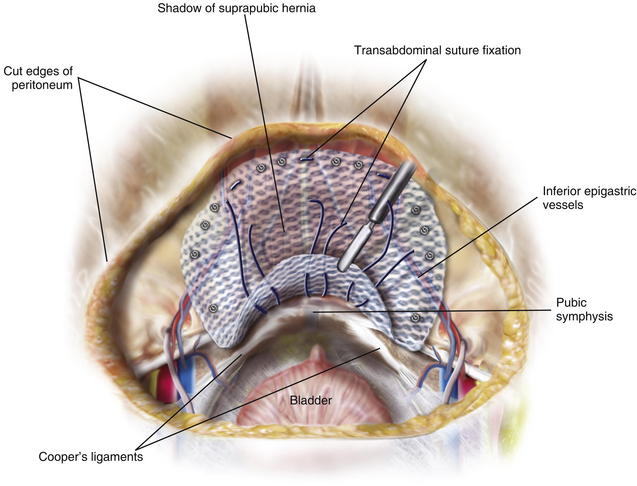

The inferior epigastric vessels are located on the opposite side of the operating surgeon and the preperitoneal space entered, mobilizing the flap medially. A preperitoneal tunnel is developed to identify Cooper’s ligament. The preperitoneal space lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels is developed toward the iliopubic tract if needed. The peritoneum is then swept away from the inferior epigastric vessels, fully mobilizing the preperitoneal space on this side. A similar dissection is performed to expose the contralateral preperitoneal space. The bladder is then mobilized off the midline using electrosurgical current. The dissection is carried down to the pubis. Cooper’s ligament is identified bilaterally, and the bladder is mobilized inferiorly into the space of Retzius. If the hernia abuts the pubis, it is important to mobilize the bladder sufficiently to allow several centimeters of mesh to be tucked under the pubis (Fig. 3-8). The mesh is fixated to Cooper’s ligament bilaterally using tacks in addition to suprapubic transabdominal suture fixation (Figs. 3-9 and 3-10). If the defect is close to the pubis, the inferior transfascial suture is placed several centimeters off the edge of the mesh. In doing so, the surgeon is able to bring the suture adjacent to the pubic bone, and the mesh drapes several centimeters inferiorly for adequate overlap. When applying tacks to the lower abdominal wall, it is important to confirm bimanual palpation of the tip of the tacker externally. This ensures the tack is placed above the iliopubic tract and avoids major neurovascular injuries. If there is excess mesh below the iliopubic tract that cannot be secured with tacks, we occasionally apply fibrin sealant to secure the inferior edge of the mesh over the iliac vessels.

The mesh is fixated to Cooper’s ligament bilaterally using tacks in addition to suprapubic transabdominal suture fixation (Figs. 3-9 and 3-10). If the defect is close to the pubis, the inferior transfascial suture is placed several centimeters off the edge of the mesh. In doing so, the surgeon is able to bring the suture adjacent to the pubic bone, and the mesh drapes several centimeters inferiorly for adequate overlap. When applying tacks to the lower abdominal wall, it is important to confirm bimanual palpation of the tip of the tacker externally. This ensures the tack is placed above the iliopubic tract and avoids major neurovascular injuries. If there is excess mesh below the iliopubic tract that cannot be secured with tacks, we occasionally apply fibrin sealant to secure the inferior edge of the mesh over the iliac vessels. 2 Subxiphoid

2 Subxiphoid

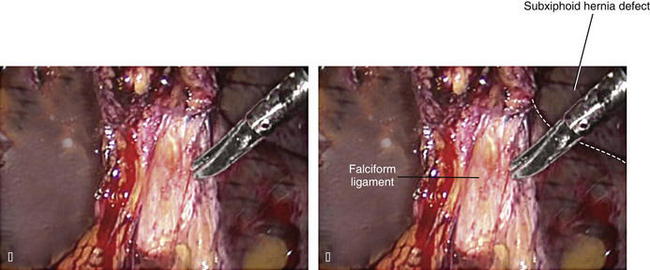

Space is created for cephalad overlap of the defect by dividing the falciform ligament toward the diaphragm. This often can be done with electrosurgical current; however, meticulous hemostasis should be confirmed at the conclusion of this step (Figs. 3-11 and 3-12).

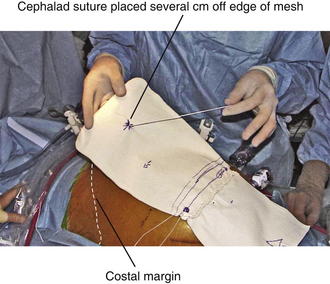

Space is created for cephalad overlap of the defect by dividing the falciform ligament toward the diaphragm. This often can be done with electrosurgical current; however, meticulous hemostasis should be confirmed at the conclusion of this step (Figs. 3-11 and 3-12). The mesh is fixated just below the costal margins bilaterally and allowed to drape generously over the diaphragm (Fig. 3-13). If the defect abuts the xiphoid process, adequate overlap can be challenging. We do not suture around ribs because of the risk of severe chronic pain, nor do we advocate placing tacks above the costal margin because of the risk of pericardial injury. In order to achieve adequate overlap, the cephalad suture can be placed several centimeters off the edge of the mesh (Fig. 3-14). The extra mesh is allowed to drape over the diaphragm. Typically this mesh doesn’t require fixation because the liver will hold it in place; however, if the surgeon is concerned, applying fibrin sealant to the diaphragm can help secure the mesh.

The mesh is fixated just below the costal margins bilaterally and allowed to drape generously over the diaphragm (Fig. 3-13). If the defect abuts the xiphoid process, adequate overlap can be challenging. We do not suture around ribs because of the risk of severe chronic pain, nor do we advocate placing tacks above the costal margin because of the risk of pericardial injury. In order to achieve adequate overlap, the cephalad suture can be placed several centimeters off the edge of the mesh (Fig. 3-14). The extra mesh is allowed to drape over the diaphragm. Typically this mesh doesn’t require fixation because the liver will hold it in place; however, if the surgeon is concerned, applying fibrin sealant to the diaphragm can help secure the mesh. 3 Lumbar

3 Lumbar

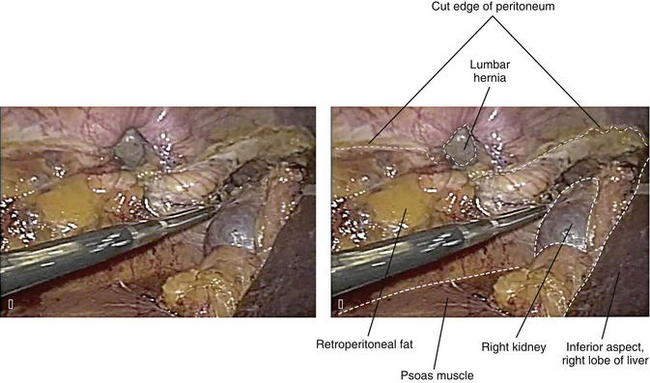

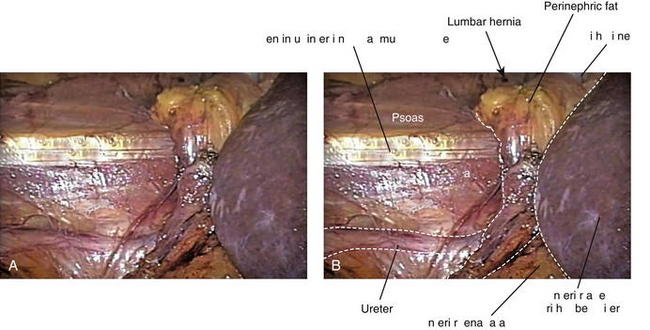

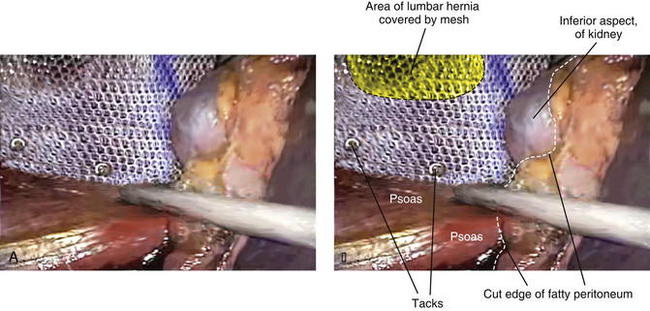

The surgeon must be comfortable with retroperitoneal exposure. In order to gain adequate posterior coverage of the defect with the mesh, the colon must be mobilized medially. Careful identification of the ureter is paramount to safe fixation of the mesh. We prefer to clearly identify the psoas muscle. Once the psoas muscle is identified and the ureters delineated, the dissection stops and any major vascular structures are avoided (Figs. 3-15 and 3-16).

The surgeon must be comfortable with retroperitoneal exposure. In order to gain adequate posterior coverage of the defect with the mesh, the colon must be mobilized medially. Careful identification of the ureter is paramount to safe fixation of the mesh. We prefer to clearly identify the psoas muscle. Once the psoas muscle is identified and the ureters delineated, the dissection stops and any major vascular structures are avoided (Figs. 3-15 and 3-16).5 Pearls/Pitfalls

Patients must understand the potential risks associated with these repairs. A complete discussion of the potential outcomes and management strategies for any neurovascular injury is paramount.

Patients must understand the potential risks associated with these repairs. A complete discussion of the potential outcomes and management strategies for any neurovascular injury is paramount. The decision to mobilize the preperitoneal space in the laparoscopic repair of suprapubic hernias should be made preoperatively to ensure that adequate equipment and expertise are available for success. Unlike mobilization of the preperitoneal space during laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair, this maneuver can be very difficult in the repair of suprapubic hernias. Often, this space has been entered multiple times because of lower abdominal or pelvic operations. This dissection can often be facilitated by developing the preperitoneal space on the medial aspect of the separated rectus muscles within the hernia sac.

The decision to mobilize the preperitoneal space in the laparoscopic repair of suprapubic hernias should be made preoperatively to ensure that adequate equipment and expertise are available for success. Unlike mobilization of the preperitoneal space during laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair, this maneuver can be very difficult in the repair of suprapubic hernias. Often, this space has been entered multiple times because of lower abdominal or pelvic operations. This dissection can often be facilitated by developing the preperitoneal space on the medial aspect of the separated rectus muscles within the hernia sac. Atypical hernias often involve nearby bony structures in close proximity to the hernia defect (pubic bone, xiphoid process, iliac crest). When selecting the appropriately sized mesh, it is paramount to incorporate extra overlap beyond that included for transabdominal suture fixation. This allows additional overlap over difficult areas where fixation is impossible or ill-advised.

Atypical hernias often involve nearby bony structures in close proximity to the hernia defect (pubic bone, xiphoid process, iliac crest). When selecting the appropriately sized mesh, it is paramount to incorporate extra overlap beyond that included for transabdominal suture fixation. This allows additional overlap over difficult areas where fixation is impossible or ill-advised. One of the most common reasons for failure after repair of an atypical hernia is lack of mesh overlap. Regardless of the approach (laparoscopic or open), the surgeon should rely heavily on mesh overlap and not mesh fixation. Any mesh fixated to the edge of the defect will likely contract over time and eventually dissociate from any bony structure. Therefore, the true key to repairing an atypical hernia is the comfort in gaining appropriate lateral and inferior dissection planes to afford mesh overlap.

One of the most common reasons for failure after repair of an atypical hernia is lack of mesh overlap. Regardless of the approach (laparoscopic or open), the surgeon should rely heavily on mesh overlap and not mesh fixation. Any mesh fixated to the edge of the defect will likely contract over time and eventually dissociate from any bony structure. Therefore, the true key to repairing an atypical hernia is the comfort in gaining appropriate lateral and inferior dissection planes to afford mesh overlap.Losanoff J.E., Basson M.D., Laker S., Weiner M., Webber J.D., Gruber S.A. Subxiphoid incisional hernias after median sternotomy. Hernia. 2007;11:473-479.

Varnell B., Bachman S., Quick J., Vitamvas M., Ramshaw B., Oleynikov D. Morbidity associated with laparoscopic repair of suprapubic hernias. American Journal of Surgery. 2008;196:983-987. discussion 987-988

Yavuz N., Ersoy Y.E., Demirkesen O., Tortum O.B., Erguney S. Laparoscopic incisional lumbar hernia repair. Hernia. 2009;13:281-286.