Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair

Key Anatomic Concepts for Laparoscopic Repair

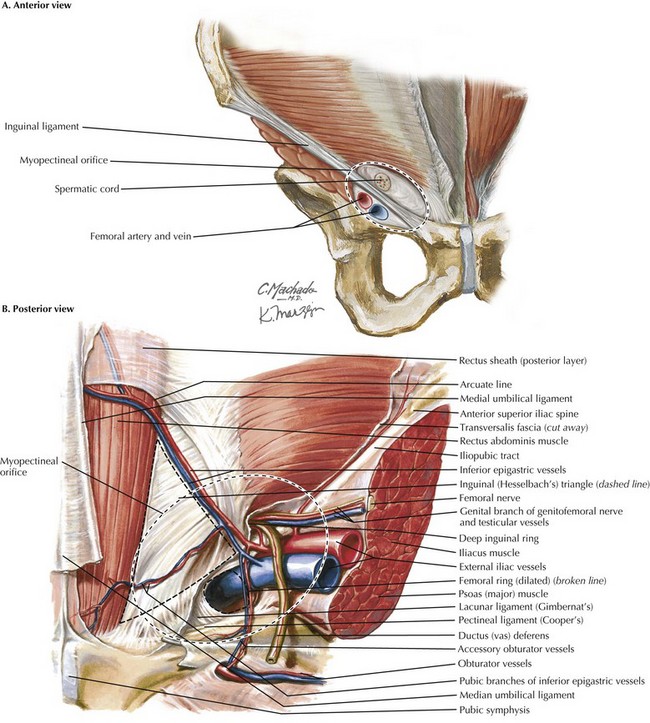

The myopectineal orifice is one of the most important anatomic features of the groin anatomy (Fig. 29-1, dashed ovals). All hernias of the groin originate from this single zone of weakness, which is covered only by transversalis fascia and peritoneum. Bisected by the inguinal ligament, the myopectineal orifice comprises the inguinal canal superiorly and the femoral canal inferiorly. The inferior border consists of the superior pubic ramus and the pectineal (Cooper’s) ligament. Medially, the myopectineal orifice is bordered by the rectus abdominis muscle and the inguinal falx (conjoined tendon). The conjoined (conjoint) tendon (fusion of internal oblique muscle and transversalis fascia) is also the superior border of the orifice. Laterally, the boundaries consist of the iliopsoas muscle and lateral border of the femoral sheath.

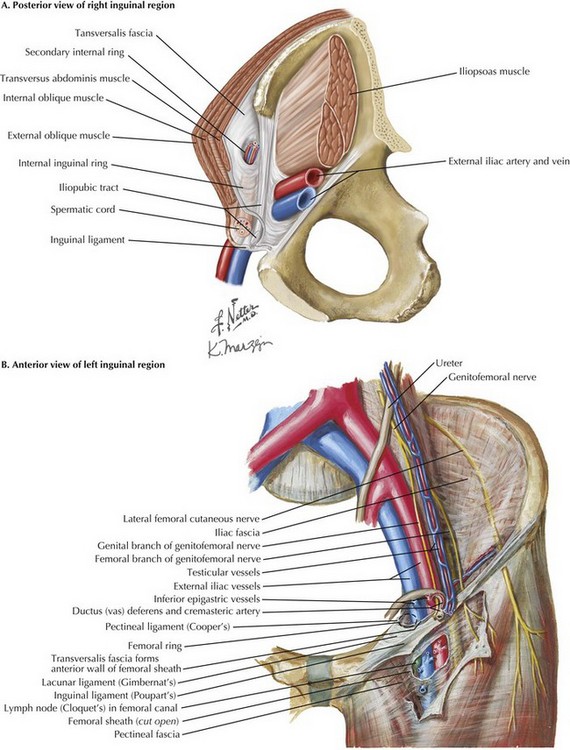

Inguinal Ligament versus Ileopubic Tract

Although a key anatomic landmark for open (anterior) inguinal hernia repair, the inguinal ligament is not seen in the laparoscopic (posterior) repair because it is an anterior lamina structure (Fig, 29-2, A). The inguinal (Poupart’s) ligament is the inferior edge of the external oblique aponeurosis, extending from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, turning posteriorly to form the “shelving edge.” This shelving edge is used to secure the inferior border of the mesh in an open inguinal hernia repair (see Chapter 28). The iliopubic tract is the continuation of the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and fascia. It is located posterior to the inguinal ligament, extends from the pubic tubercle medially, and passes over the femoral vessels to insert on the ASIS laterally. This posterior lamina structure is an important landmark in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair; lateral to the internal ring, no tacks should be placed below the iliopubic track because of the risk of injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous, genitofemoral, and femoral nerves.

Pectineal Ligament

The pectineal (Cooper’s) ligament refers to the periosteum found along the superior ramus of the pubic bone, posterior to the iliopubic tract (Fig. 29-2, B). The pectineal ligament is an extension of the lacunar (Gimbernat’s) ligament, which connects the inguinal ligament to Cooper’s ligament near their insertion site at the pubic tubercle. Cooper’s ligament is frequently used for medial fixation of the mesh in a laparoscopic hernia repair.

Inguinal Geometry

Hesselbach’s (inguinal) triangle is formed by the lateral border of the rectus sheath, inferior epigastric vessels, and inguinal ligament (see Fig. 29-1, B). Direct hernias occur through this space, medial to the inferior epigastric arteries. Indirect hernias are found lateral to Hesselbach’s triangle and the lateral umbilical ligaments, which contain the epigastric arteries.

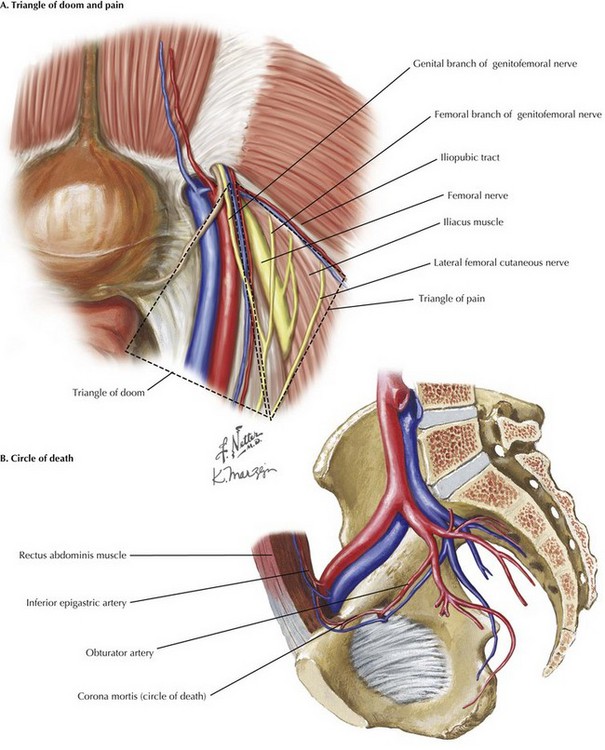

The “triangle of doom” contains the external iliac artery and vein (Fig. 29-3, A). It is formed medially by the vas deferens, laterally by the gonadal vessels, and inferiorly by the peritoneal edge. No tacks should be placed in this triangle to avoid injury to the iliac vessels.

The “triangle of pain” is defined by the gonadal vessels medially, iliopubic tract laterally, and peritoneal edge inferiorly (Fig. 29-3, A). It contains the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve, and the femoral nerve. Tacks in this area risk nerve entrapment, causing pain on the anterolateral aspect of the thigh.

The “circle of death,” also known as corona mortis, is a vascular ring formed by the anastomosis of an aberrant artery from the external iliac artery with the obturator artery, branching from the internal iliac artery (Fig. 29-3, B). Tacks should be avoided here because profuse bleeding can occur if the ring is injured.

Transabdominal Preperitoneal Approach

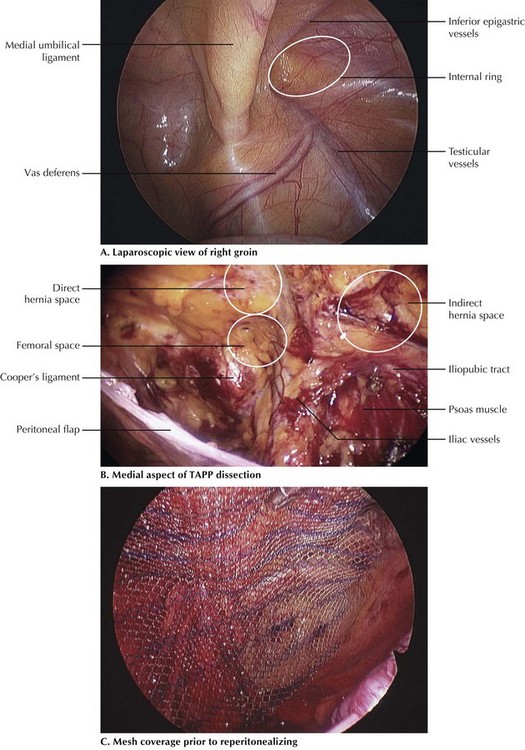

Next, both inguinal areas are inspected for hernias. Identification of the following landmarks are critical to begin dissection: medial umbilical ligament (containing obliterated umbilical artery), testicular vessels, inferior epigastric vessels (lateral umbilical ligament), and external iliac vessels (Fig. 29-4, A).

FIGURE 29–4 Laparoscopic dissection: transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach to inguinal hernia.

To begin the incision, the laparoscopic scissors are used to make a transverse incision in the peritoneum, starting at the medial umbilical ligament and continuing laterally along the anterior abdominal wall, ending just short of the ASIS. This incision line essentially parallels the arcuate line of Douglas. The peritoneum is then grasped along its edge and dissected away from the transversalis fascia, which remains on the anterior abdominal wall. When creating this peritoneal flap, great care must be taken to avoid injury to the epigastric vessels and to sweep all layers toward the anterior abdominal wall, except the thin peritoneal layer. This pocket is dissected out medially to expose the pubic symphysis and Cooper’s ligament, a white glistening structure along the superior pubic ramus (Fig. 29-4, B). Lateral exposure continues 3 to 5 cm lateral to the opening of the internal inguinal ring and inferiorly until the edge of the psoas muscle is visible.

Once the peritoneal sac is completely reduced and the pocket enlarged to expose the entire myopectineal orifice, the pocket is ready for placement of the mesh. The surgeon must inspect the peritoneum for any defects made during dissection that could allow exposure of the mesh to the abdominal cavity. All defects must be repaired, or mesh with a barrier coating should be selected. The mesh is then introduced into the abdominal cavity through the umbilical port, then placed in the peritoneal pocket and unrolled to cover the entire myopectineal orifice with significant overlap. Essentially, the mesh is then positioned to cover the direct, indirect, and femoral openings. The authors typically use mesh that is 14 cm in medial-to-lateral dimension by 11 to 12 cm in craniocaudal direction (Fig. 29-4, C).

The authors use an endoscopic tacker to fixate the mesh medially to Cooper’s ligament, anteromedially to the rectus abdominis muscle, and anterolaterally to the area above the internal ring. If tacks are used lateral to the internal inguinal ring, all tacks must be placed above the iliopubic tract, to avoid the triangle of pain and triangle of doom (see Fig. 29-3, A). The surgeon ensures this placement by manually palpating the tip of the tacker from the outside the abdominal cavity, above the inguinal ligament. If desired, fibrin glue is an excellent adjunct for mesh fixation inferiorly.

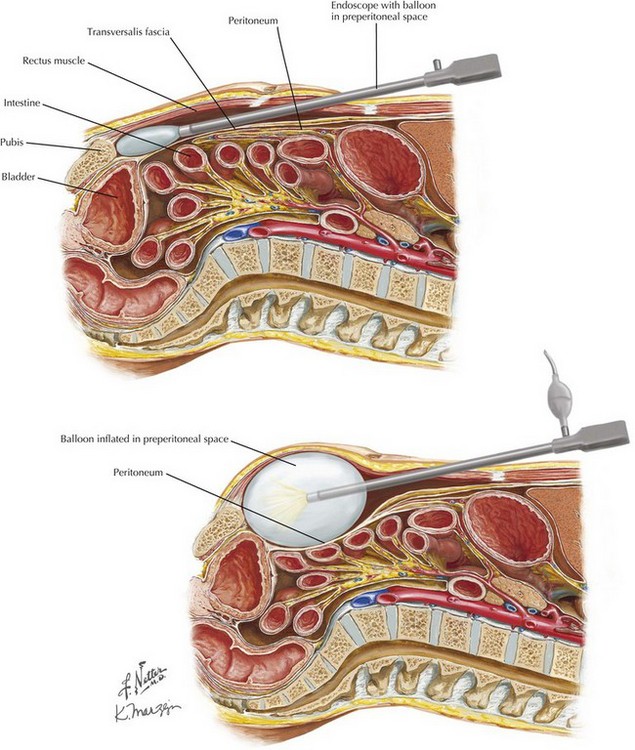

Totally Extraperitoneal Approach

The patient is positioned supine with both arms tucked at the sides and a single laparoscopic tower at the foot of the bed. Port placement differs from TAPP technique in that all ports for a TEP approach are placed vertically in the midline. To begin, a 10-mm infraumbilical incision (port) is made, and the anterior rectus sheath on the side of the hernia defect is opened longitudinally. The rectus abdominis muscle fibers are retracted laterally to expose the posterior rectus sheath. Finger dissection is performed to free the muscle fibers from their posterior attachments, to accommodate the dissection balloon. The key here is to avoid entering the peritoneal cavity, since the dissection plane is in the preperitoneal space. The dissecting-balloon trocar is slid into the space between the rectus muscles anteriorly and the transversalis fascia and peritoneum posteriorly until the tip reaches the pubic symphysis (Fig. 29-5). Great care must be taken in this step not to injure the epigastric vessels. Insufflation is done under direct laparoscopic visualization until an adequate space is developed. The dissecting balloon is deflated and replaced with a blunt-tipped trocar.