Laparoscopic and Open Cholecystectomy

Gallbladder Anatomy

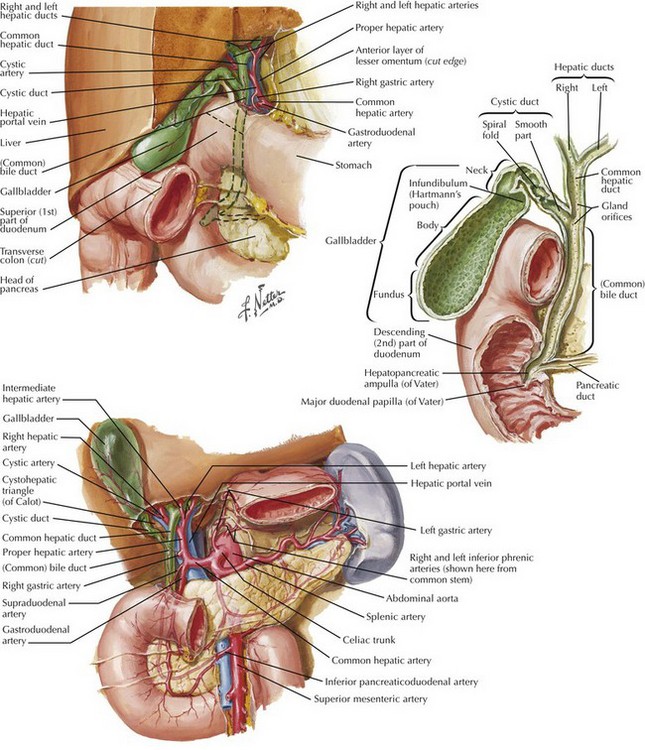

The gallbladder is an ovoid bag located in the gallbladder fossae of the liver capable of storing up to 50 mL of bile. The gallbladder has a fundus, body, and infundibulum, and it continues by the cystic duct to join the common hepatic duct (CHD) and form the common bile duct (CBD) (Fig. 12-1).

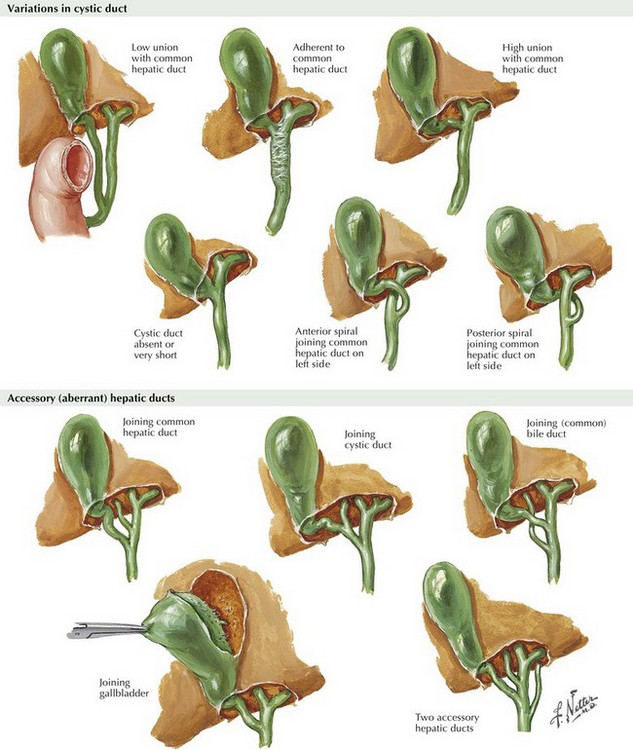

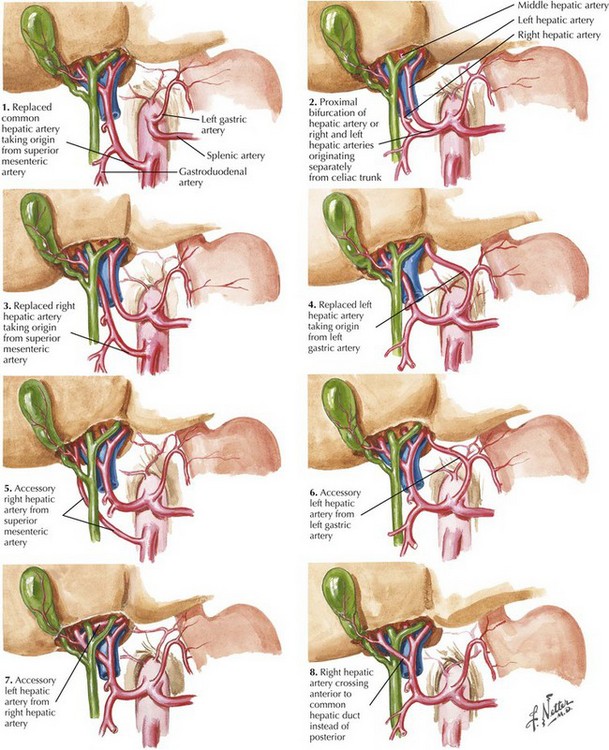

The right hepatic artery passes behind the CHD, where the cystic artery originates, and reaches the gallbladder at the cystic node level. This represents the most common anatomic variation but is present in only 50% to 70% of patients. The surgeon must be aware of all anatomic variations of the biliary tree and hepatic artery to avoid injury to the CBD and vascular structures (Figs. 12-2 and 12-3).

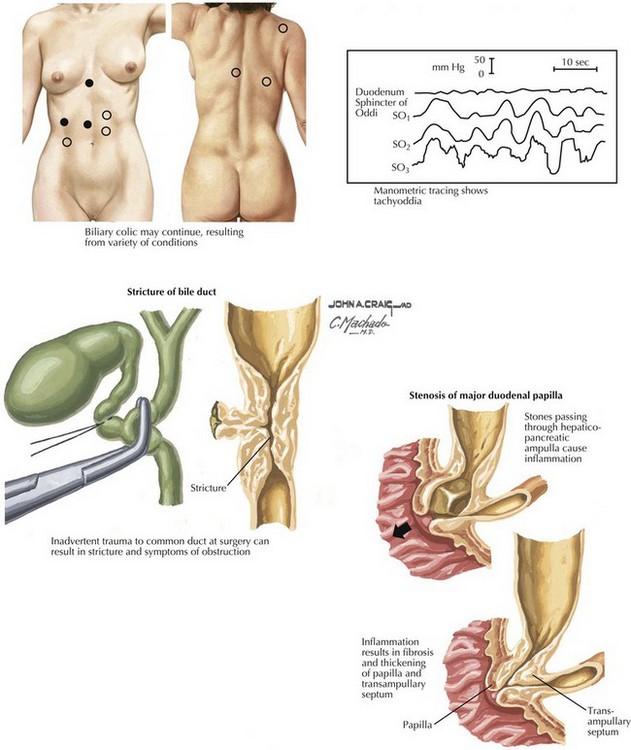

Symptomatic Gallstones: Clinical Manifestations

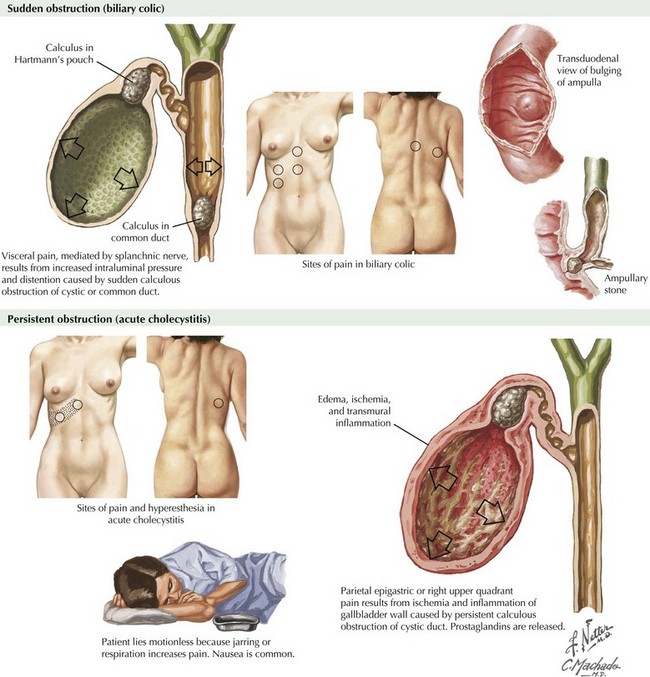

Although more than 60% of adults older than 60 have gallstones in Western countries, only 20% become symptomatic. The hallmark of symptomatic gallstone disease is abdominal pain, usually in the right upper quadrant (RUQ), with radiation to the back, right shoulder, or epigastrium (Fig. 12-4). Pain classically occurs 30 minutes to 2 hours after the ingestion of a fatty meal and varies in severity. Pain typically is not constant and may be associated with nausea and vomiting. This presentation as biliary colic could progress to an acute inflammatory state promoted by the impaction of a stone in the neck of the gallbladder (see Fig. 12-1).

Patients with acute cholecystitis have constant RUQ pain, tenderness at deep palpation (a surrogate of Murphy sign), hyperthermia, and elevated white blood cell count (Fig. 12-4). The stone may pass to the CBD, causing obstruction and development of jaundice. A patient with RUQ pain, fever, leukocytosis, and jaundice, with or without mental changes and hemodynamic compromise, has cholangitis, a true surgical emergency. Other stones produce distal obstruction of the CBD and pancreatic duct, causing an acute episode of pancreatitis. However, most stones that reach the CBD pass into the duodenum, to be passed without consequence.

Laparoscopic Approach

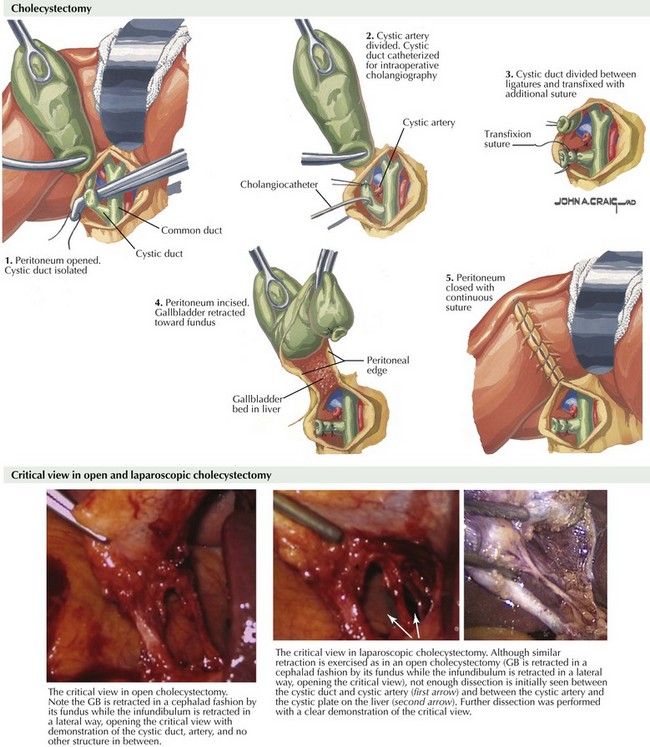

The Critical View

Once the cystic node is identified, division of the anterior and posterior peritoneal folds is performed, followed by blunt dissection of Calot’s triangle until demonstration of (1) a tubular structure that goes from the gallbladder infundibulum toward the porta hepatis, (2) a tubular structure with arterial pulse running from the porta hepatis to the gallbladder, and (3) liver tissue in the background with no other structure in between (Fig. 12-5).

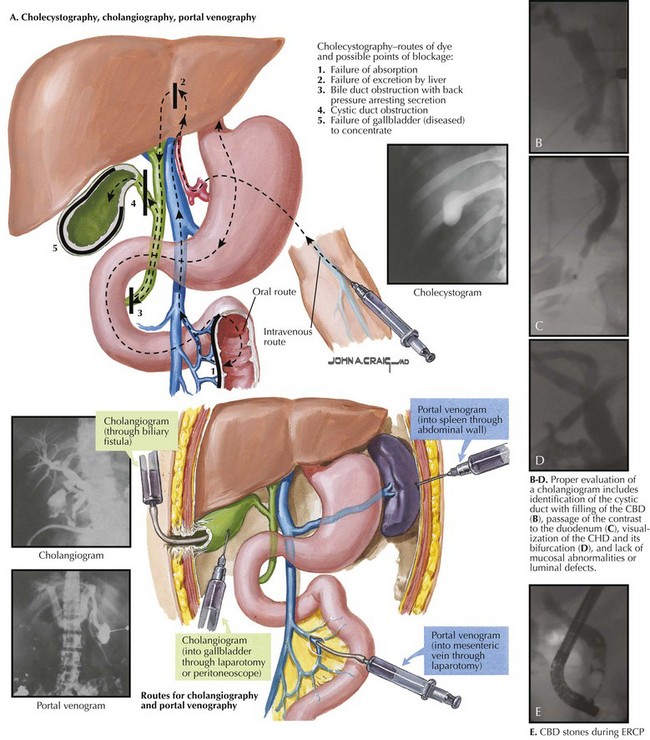

Intraoperative Ultrasound and Cholangiography

The choice of imaging modality is determined by surgical indication and the practice styles of individual surgeons. Intraoperative ultrasound (IOU) has a high degree of sensitivity and specificity for intraluminal CBD defects, lymphadenomegaly, and vascular assessment. IOU also can be performed on both the liver and the pancreas. It requires a 12-mm trocar for the introduction of the laparoscopic probe. For the assessment of biliary anatomy, mucosal lesions, or intraluminal defects, IOC is favored (Fig. 12-6, A).

FIGURE 12–6 Intraoperative imaging in cholecystectomy.

CBD, Common bile duct; CHD, common hepatic duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Familiarity with the different kits available for cholangiography is advised. The author uses a dynamic cholangiogram with fluoroscopy to observe the infusion of 50% diluted contrast through a preflushed soft, 5-Fr tube with a 1-mL occlusion balloon. Proper evaluation of a cholangiogram includes identification of the cystic duct with filling of the CBD (Fig. 12-6, B), passage of the contrast to the duodenum (12-6, C), visualization of the CHD and its bifurcation (12-6. D), and lack of mucosal abnormalities or luminal defects. In some patients, the administration of intravenous glucagon is required to achieve passage of contrast into the duodenum.

Meniscal morphology with obstruction should prompt the search for a CBD stone, and a mucosal abnormality signals possible malignancy (Fig 12-6, E). If segmental biliary duct injury is suspected, identification of all intrahepatic segmental ducts is mandatory.

Conversion to Open Cholecystectomy

Open cholecystectomy is performed most commonly through a right subcostal incision (Kocher incision), but it can also be approached through an upper midline incision. The dissection starts exactly as described for the laparoscopic approach until the critical view is achieved (see Fig. 12-5). Caution should be exercised if vigorous traction of the cystic duct is performed, because it may result in avulsion of the cystic duct from the CBD or inclusion of the CBD during placement of the cystic duct clamp, as illustrated in Figure 12-7.

Garden, OJ. Iatrogenic injury to the bile duct. Br J Surg. 1991;78(12):1412–1413.

Mercado, MA, Domínguez, I. Classification and management of bile duct injuries. World. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;3(4):43–48.

Sicklick, JK, Camp, MS, Lillemoe, KD, et al. Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241(5):786–792.

Strasberg, SM, Hertl, M, Soper, NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101–125.