Chapter 22 Lactose Malabsorption Testing

Introduction

Introduction

Lactose malabsorption results from the inability to properly digest lactose, the disaccharide found in mammalian milk. Lactase is an enzyme in the brush border (microvilli) of the small intestine responsible for cleaving lactose into absorbable monosaccharides. Lactase enzyme deficiency leads to lactose malabsorption as the gut is unable to absorb the larger diasaccharide. When symptoms such as diarrhea, bloating, flatulence, or abdominal discomfort result from this malabsorption, a diagnosis of lactose intolerance is given. Lactose intolerance affects an estimated 25% of Americans and 75% of adults worldwide.1 As shown in Table 22-1, the condition occurs in people of all ethnic backgrounds, with a near 100% prevalence observed in Asians. Within the United States, prevalence parallels country of origin, with the highest rates in African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans.2

TABLE 22-1 Prevalence of Lactose Intolerance by Ethnic Group

| GROUP | PREVALENCE (%) |

|---|---|

| African blacks | 97-100 |

| Asians | 90-100 |

| North American blacks | 70-75 |

| Mexicans | 70-80 |

| Persons of Mediterranean descent | 60-90 |

| Persons of Jewish descent | 60-80 |

| North American whites | 7-15 |

| Northern Europeans | 1-5 |

The generalized nature of abdominal symptoms of lactose intolerance can obscure proper diagnosis,3 resulting in symptom management through medical intervention. However, when properly diagnosed, lactose intolerance may be treated with patient education, lactase supplementation, and dietary modifications,4 eliminating the need for medical interventions. In patients experiencing symptoms, a nutritional history and objective measures of lactose malabsorption can lead to the diagnosis of lactose intolerance. Objective measures for lactose malaborption include stool pH testing, lactose tolerance testing, and hydrogen/methane breath testing. In addition, genomic tests are also available to assess the presence or absence of polymorphisms linked to lactase enzyme deficiency.

Controversy surrounds the subject of lactose intolerance stemming from the dramatic decrease in dairy consumption that can result from its diagnosis. Numerous studies showed a correlation between decreased dairy consumption and a rise in calcium-dependent conditions, such as osteoporosis, heart disease, and colon cancer.5–10 Studies also indicated that food-based calcium was a better source of this nutrient than supplements. Because dairy foods are the richest and best-absorbed dietary sources of calcium, careful diagnosis should be made before these foods are eliminated from the patient’s diet. Dietary limitation of calcium rich foods should only be done in the context of objectively proven lactose intolerance. Many patients with lactose malabsorption are able to consume moderate amounts of lactose without symptoms, so both the diagnosis and treatment should be pursued under professional guidance.11

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

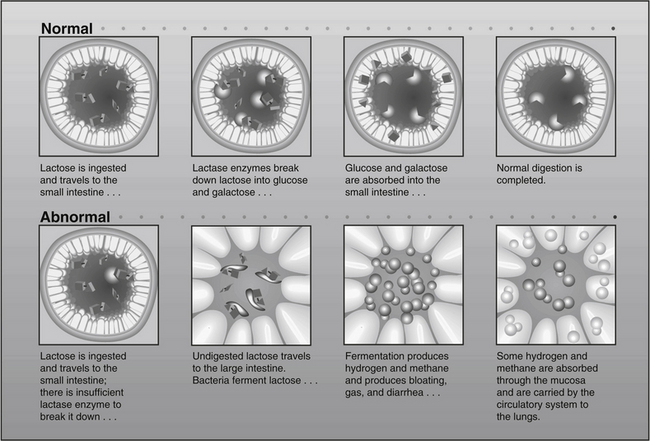

Lactose is a disaccharide that can be hydrolyzed by the lactase enzyme lactase-phlorizin hydrolase (LPH) into glucose and galactose, which are actively absorbed in the small intestine (Figure 22-1). When LPH activity is decreased in the brush border (microvilli) of the distal duodenum and proximal jejunum, then lactose malabsorption results. The presence of lactose malabsorption does not always result in lactose intolerance. Only when the amount of lactose ingested exceeds digestive capacity does lactose persist in the lumen, ultimately reaching the colon, where it may lead to osmotic retention of fluid and bacterial fermentation, thus causing the symptoms characteristic of lactose intolerance (see Figure 22-1).12 Therefore, symptoms of lactose intolerance often require several contributing factors in addition to LPH deficiency, including (1) relatively high lactose load, (2) gut dysmotility13 (3) rapid small bowel transit, (4) heightened visceral sensitivity,14 and/or (5) altered bowel flora.15

Adult-Type (Primary) Lactose Deficiency

Adult-Type (Primary) Lactose Deficiency

The majority of the world’s population has a normal decrease in LPH synthesis after weaning. This common autosomal recessive genotype confers the phenotype of primary lactase deficiency (lactase nonpersistence). Genetically, nucleotide sequences in the distal enhancer region of the LCT gene (chromosome 2), which encodes LPH, appear responsible for this developmentally programmed loss of transcription.16

It is theorized that maintaining the ability to digest lactose into adulthood (lactase persistence) is the result of a relatively new evolutionary genetic mutation that occurred after the domestication of farm animals.17 Preservation of lactase synthesis has been associated with several distinct single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on the distal enhancer region of the LCT gene (–13910C>T, –13915T>G, –14010G>C). Although the presence of any these SNPs suggests lactase persistence, their absence does not equate to lactase nonpersistence, because there appear to be other SNPs that have not yet been determined.18

Acquired (Secondary) Lactase Deficiency

Acquired (Secondary) Lactase Deficiency

Because LPH is located in the brush border (microvilli) of gut mucosal cells, LPH deficiency may be secondary to diseases that damage these cells. Lactose intolerance has been observed as a secondary feature in celiac disease,19 tropical sprue, acute gastroenteritis, chemotherapy-induced mucositis,20 cystic fibrosis, alcoholism,21 pelvic radiation therapy,22 and Crohn’s disease.23 In secondary lactase deficiency, treating the underlying condition and resultant restoration of mucosal integrity often restores lactase activity.24

Congenital Lactase Deficiency

Congenital Lactase Deficiency

Congenital lactase deficiency is a rare inborn error of metabolism characterized by very low or absent lactase activity in the intestinal microvilli at birth. Unlike lactase nonpersistence mutations, which affect upstream enhancer regions of LCT, mutations in the LCT gene itself appear to be responsible for congenital lactase deficiency.25 Clinical symptoms include severe diarrhea, dehydration, and malnutrition, and often appear during the first week with the consumption of lactose. Separately, preterm infants may exhibit symptoms of lactase deficiency if born before 34 weeks’ gestation, a condition called developmental lactase deficiency.26 As expected, preterm infants can gain function of the lactase enzyme with time.

Lactose Intolerance Versus Dairy Allergy

Lactose Intolerance Versus Dairy Allergy

Lactose intolerance and dairy allergy are separate pathologies. Lactose intolerance results from the maldigestion of dairy carbohydrate (lactose), whereas dairy allergy is an immune response to dairy proteins (e.g., casein, lactalbumin, whey). Dairy allergy may involve reactions (e.g., systemic anaphylaxis) that affect the gastrointestinal tract, skin, respiratory tract, or multiple systems. These immediate reactions are often mediated by immunoglobulin-E (IgE) and can cause severe morbidity and even death; however, in such cases, dietary elimination of dairy products is associated with good prognosis.27 The prevalence of IgE-mediated allergic reaction to dairy protein in the general population is estimated at 1% to 3%, being highest in infants and lowest in adults. However, the prevalence of IgG-mediated allergic reactions may be higher.

Diagnosis of Lactose Intolerance

Diagnosis of Lactose Intolerance

Clinical suspicion of lactose intolerance should be raised when foods containing milk or milk products produce symptoms of gas, bloating, cramping, or diarrhea (Box 22-1). A short course of dietary manipulation, with careful removal of milk containing products, can strengthen the case for lactose intolerance as a diagnosis. Testing stool acidity, oral lactose tolerance testing, breath tests for hydrogen and methane, and/or genomic evaluation for LCT haplotypes should be used to confirm the diagnosis. Because the presence of lactase deficiency does not always result in lactose intolerance, genomic testing should never be used as a sole determinant in diagnosis. Breath testing provides the most reliable noninvasive means of determining lactose malabsorption, but must be used in the context of symptomology to make the diagnosis of lactose intolerance. In contrast, a positive breath test coupled with the absence of LCT haplotyping indicating primary lactase deficiency suggests a secondary causation, the diagnosis of which should be pursued.

There have been conflicting results regarding the presence of lactose intolerance in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). By definition, the diagnosis of IBS is a functional diagnosis that is made when all organic causes of symptoms have been ruled out. However, studies have shown that IBS patients have a high rate of lactose intolerance, with resolution of IBS symptoms upon lactose limitation or removal.28–30 Rana et al31 found that patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS had a higher incidence of lactose intolerance (82%) than patients who had either spastic-type IBS or features of both IBS types. For this reason, lactose intolerance should always be investigated in cases of IBS, a condition that affects up to 20% of Americans.32

A number of studies have suggested that transient lactose intolerance is also associated with infantile colic.33,34 For susceptible children with lactose maldigestion, only 12 grams of lactose (~1 cup of milk) daily has been shown to be associated with increased abdominal pain.35

Nutritional History

A detailed history of the patient’s average consumption of lactose-containing food should be obtained. Often, patients do not consider yogurt, ice cream, chocolate milk, and milk ingested with cereal as important sources of lactose. They also may not be aware that lactose is added to many nondairy products to provide texture, flavor, and browning, and to absorb flavors, aromas, and food colors (Box 22-2). In addition, because of its excellent binding ability, lactose is contained in many drugs and over-the-counter products (Box 22-3). Identifying all sources of lactose is necessary to (1) identify the potential relationship between gastrointestinal symptoms and lactose consumption and (2) develop an effective lactose-free diet, if necessary.

BOX 22-2 Sources of Lactose

Hidden Sources

Artificial sweeteners containing lactose

Breads, biscuits and crackers, doughnuts made with milk

Breakfast and baby cereals containing milk solids

Buttered or creamed foods (soups and vegetables)

Cake and pudding mixes, many frostings

Hot dogs, luncheon meats, sausage, hash, processed and canned meats

Empirical Testing (Trial Elimination of Milk Products from the Diet)

If the patient experiences symptoms after consuming food products containing lactose, a temporary exclusion of all lactose-containing products from the diet as a preliminary diagnostic procedure may be helpful. However, diagnosis of lactose intolerance should not be based solely on elimination of milk products. This subjective test may be misleading if hidden sources of lactose (see Box 22-3) are not removed or if unrelated symptoms coincidently abate during this period.36

Breath Testing

Breath testing is the method of choice for diagnosing lactose maldigestion.37 It is sensitive and specific,38 simple to perform, noninvasive, and inexpensive.36 Breath testing is based on the ability of intestinal microbes to ferment carbohydrates, in this case lactose, producing hydrogen or methane in the process. A fraction of these gases naturally diffuses from the bowel to the circulation and is eliminated via the lungs. Because there is no other metabolic production of hydrogen and methane, pulmonary excretion of these gases may be used as an indirect measure of lactose maldigestion, indicating lactase deficiency.39

The benefits of breath testing are as follows:

• Its results correlate strongly with the symptoms of lactose intolerance.40

• It can be done at home by the patient or in the physician’s office.41

• The lower challenge dose of lactose causes significantly fewer side effects than the large doses used in blood and urine galactose tests.42

• The breath hydrogen/methane test is the standard in pediatric cases in which other tests would be difficult to perform.43–45

Historically, breath testing measured hydrogen only. However, Tormo et al46 showed that methane is produced instead of hydrogen in some patients with lactose malabsorption. They concluded that measuring both gases was necessary for accurate diagnosis of lactose maldigestion. Other researchers suggested that although methane was produced predominantly in some cases, hydrogen production correlated more strongly with symptoms; therefore, hydrogen testing alone might be sufficient for the diagnosis of lactose intolerance.47,48 Breath testing using a radiolabeled carbon molecule (13C) in the lactose structure, showed poor correlation with lactose intolerance, as evidenced by poor 13CO2 output by the lungs.40

Procedure

After an overnight fast, a baseline breath sample is collected 30 minutes after rising. The patient then ingests a challenge dose of lactose (up to a maximum of 25 grams), and breath samples are collected 1, 2, and 3 hours after ingestion of the challenge dose.49,50

Interpretation

If lactose maldigestion is present, breath levels of hydrogen or methane will rise within 1 to 2 hours after ingesting the lactose challenge. As little as 2 grams of carbohydrate reaching the colon produces a detectable increase in breath hydrogen.51

Hydrogen and Methane Responses

The normal breath hydrogen level in a healthy, fasting patient is less than 10 ppm. Patients with lactose malabsorption show an increase in breath hydrogen concentration of 20 ppm or more during the test.52,53

The normal breath methane level in a fasting patient is 0 to 7 ppm. An increase of at least 12 ppm of methane alone during the test is considered positive for lactose malabsorption, regardless of the hydrogen response.54–56

If both breath hydrogen and methane rise after a lactose challenge, the two responses are added to estimate the degree of malabsorption. The rises in breath hydrogen and methane levels together must be 20 ppm or more to suggest lactose malabsorption.56 The extent of elevation relates to the degree of malabsorption.

False-Positive Results

• Fiber intake. Fiber should be avoided 24 hours before the test. Ingesting fiber in food or in supplements increases fermentation and hydrogen production.57–59

• Exposure to tobacco smoke. Tobacco smoke increases hydrogen levels and should be avoided immediately before and during testing.60

• Sleeping. Sleeping between breath sample collections may increase both hydrogen and methane levels.61

False-Negative Results

• Use of lactase supplements.42

• Use of antibiotics before the test. Antibiotics decrease the bacteria that ferment lactose.62

• Use of laxatives or enemas before the test. These decrease hydrogen and methane responses in patients with lactose malabsorption and reduce fermentation in the colon.63

• Severe diarrhea or hyperacidic colon contents. Hyperacidity inhibits the production of hydrogen and promotes the production of methane by colonic bacteria.64,65

High Baseline Levels

A baseline breath hydrogen level more than 20 ppm can be due to:

• Possible small intestine bacterial overgrowth.66 Elevated fasting levels of hydrogen occur in up to one third of patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth67 and may be caused by the fermentation of endogenous brush-border glycoproteins.68

• Small intestine bacterial overgrowth may elevate baseline methane readings as well.54,66,68,69

Genomic Testing

Genomic testing requires a single blood sample and avoids the diet restrictions, lengthy collection regimen, and potential for abdominal symptoms that are associated with using an oral lactose challenge. The LCT gene on chromosome 2 encodes for the enzyme LPH, and wild type is associated with lactase nonpersistence. Lactase persistence is associated with two polymorphisms on the enhancer region upstream from LCT, C/T13910 and G/A22018. Heterozygotes are considered to have lactase persistence but with intermediate lactase activity. Homozygotes T/T13910 and G/G22018 have lactase persistence genotype, whereas C/C and G/G homozygotes carry the wild type nonpersistence genotype. Genomic testing, although useful, only establishes a lactase enzyme deficiency, the presence of which does not always lead to lactose intolerance symptoms. Heterozygotes, although considered carriers of lactase persistence genotyping, can have bouts of impaired lactase activity due to stress or infection, rendering intermittent bouts of lactose intolerance.70 Therefore, testing for lactose malabsorption through an objective measure of lactose malabsorption, such as hydrogen breath testing, is still warranted.71

Blood Testing

Lactose tolerance testing (LTT) was formerly used, but has been replaced by more sensitive breath testing as previously described. LTT required a large dose of glucose challenge, up to 50 grams, which often led to abdominal symptoms that are avoided with the lower doses used in breath testing. If the rise in serum glucose after challenge was less than 26 mg/dL during the ensuing 2 hours, then lactose maldigestion was presumed. Another similar test uses radiolabeled lactose,13 C-lactose. Although it has been shown to have the ability to differentiate between those who can digest lactose and those with maldigestion, this method has not been evaluated for its ability to identify symptoms directly related to lactose intolerance,66 and it is not available clinically.

Summary

Summary

The majority of the world’s population is lactase deficient. However, lactose intolerance may not develop in all of these individuals. A comprehensive evaluation that incorporates diagnostic testing, the patient’s nutritional history, and the relationship between diet and gastrointestinal symptoms is necessary for an accurate diagnosis. Proper diagnosis of lactose intolerance allows for dietary modifications that may allow a limited amount of dairy products in some lactose intolerant individuals. Exclusion of lactose containing foods altogether should be done only for those requiring strict avoidance, with careful attention to replacement of lost nutrients such as calcium. Breath testing of hydrogen/methane production after a lactose challenge is the diagnostic method of choice.

1. Srinivasan R., Minocha A. When to suspect lactose intolerance: symptomatic, ethnic, and laboratory clues. Postgrad Med. 1998;104:109–111. 115-116, 122-123

2. National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse. A service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Lactose Intolerance. Last updated Feb 24,, 2010. http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/lactoseintolerance. Accessed 11/28/2010

3. Vernia P., Di Camillo M., Marinaro V. Lactose malabsorption, irritable bowel syndrome and self-reported milk intolerance. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33:234–239.

4. Rusynyk R.A., Still C.D. Lactose intolerance. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2001;101:S10–S12.

5. Park Y.K., Yetley E.A., Calvo M.S. Calcium intake levels in the United States: issues and considerations. http://www.fao.org/DOCREP/W7336T/w7336t06.htm. Accessed 8/30/2011

6. Lipkin M., Newmark H. Calcium and the prevention of colon cancer. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1995;22:65–73.

7. Appel L.J., Moore T.J., Obarzanek E., et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1117–1124.

8. Griffith L.E., Guyatt G.H., Cook R.J., et al. The influence of dietary and nondietary calcium supplementation on blood pressure: an updated metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:84–92.

9. Lupton J.R. Dairy products and colon cancer: mechanisms of the protective effect. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:1065–1066.

10. Baron J.A., Beach M., Mandel J.S., et al. Calcium supplements for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. Calcium Polyp Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:101–107.

11. Aurisicchio L.N., Pitchumoni C.S. Lactose intolerance: recognizing the link between diet and discomfort. Postgrad Med. 1994;95:113–116. 119-120

12. Berkow R., Fletcher A.J. The Merck manual, 16th ed.. Rahway, NJ: Merck. 1992:822–830.

13. Yamada T., Alpers D.H. Textbook of Gastroenterology, 4th ed., Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

14. Di Stefano M., Miceli E., Mazzocchi S., et al. Visceral hypersensitivity and intolerance symptoms in lactose malabsorption. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:887–895.

15. Almeida J.A., Kim R., Stoita A., et al. Lactose malabsorption in the elderly: role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:146–154.

16. Ingram C., Mulcare C., Itan Y., et al. Lactose digestion and the evolutionary genetics of lactase persistence. Human Genetics. 2009;124:579–591.

17. Enattah N.S., Sahi T., Savilahti E., et al. Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Nat Genet. 2002;30:233–237.

18. Ingram C., Raga T., Tarekegn A., et al. Multiple Rare Variants as a Cause of a Common Phenotype: Several Different Lactase Persistence Associated Alleles in a Single Ethnic Group. J Molecular Evolution. 2009;69:579–588.

19. Ojetti V., Nucera Ga, Migneco A., et al. High prevalence of celiac disease in patients with lactose intolerance. Digestion. 2005;71:106–110.

20. Osterlund P., Ruotsalainen T., Peuhkuri K., et al. Lactose intolerance associated with adjuvant 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:696–703.

21. Keshavarzian A., Iber F.L., Dangleis M.D., Cornish R. Intestinal-transit and lactose intolerance in chronic alcoholics. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;44:70–76.

22. Henriksson R., Franzen L., Sandstrom K., et al. Effects of active addition of bacterial cultures in fermented milk to patients with chronic bowel discomfort following irradiation. Support Care Cancer. 1995;3:81–83.

23. von Tirpitz C., Kohn C., Steinkamp M., et al. Lactose intolerance in active Crohn’s disease: clinical value of duodenal lactase analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:49–53.

24. Kanabar D., Randhawa M., Clayton P. Improvement of symptoms in infant colic following reduction of lactose load with lactase. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2001;14:359–363.

25. Torniainen S., Freddara R., Routi T., et al. Four novel mutations in the lactase gene (LCT) underlying congenital lactase deficiency (CLD). BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:8.

26. Heyman M.B., Nutrition. Lactose Intolerance in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1279–1286.

27. Bahna S.L. Cow’s milk allergy versus cow milk intolerance. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:56–60.

28. Bernardessilva C., Pereira A., Defatimaalvesdamota G., et al. Lactase persistence/non-persistence variants, C/T_13910 and G/A_22018, as a diagnostic tool for lactose intolerance in IBS patients. Clin Chimica Acta. 2007;386:7–11.

29. Gremse D.A., Nguyenduc G.H., et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and lactose maldigestion in recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. South Med J. 1999;92:778–781.

30. Vernia P., Ricciardi M.R., Frandina C., et al. Lactose malabsorption and irritable bowel syndrome: effect of a long-term lactose-free diet. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1995;27:117–121.

31. Rana S.V., Mandal A.K., Kochhar R., et al. Lactose intolerance in different types of irritable bowel syndrome in north Indians. Trop Gastroenterol. 2001;22:202–204.

32. Zaman A. Irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Cornerstone. 2002;4:22–33.

33. Moore D.J., Robb T.A., Davidson G.P. Breath hydrogen response to milk containing lactose in colicky and noncolicky infants. J Pediatr. 1988;113:979–984.

34. Gremse D.A., Greer A.S., Vacik J. Abdominal pain associated with lactose ingestion in children with lactose intolerance. Clin Pediatr. 2003;42:341–345.

35. Murphy M.S., Sood M., Johnson T. Use of the lactose H2 breath test to monitor mucosal healing in coeliac disease. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:141–144.

36. Montes R.G., Perman J.A. Lactose intolerance. Pinpointing the source of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms. Postgrad Med. 1991;89:175–178. 181-184

37. Moore B.J. Dairy foods: are they politically correct? Nutr Today. 2003;38:82–90.

38. Newcomer A.D., McGill D.B., Thomas P.J. Prospective comparison of indirect methods for detecting lactase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:1232–1236.

39. Brummer R.J., Armbrecht U., Bosaeus I., et al. The hydrogen (H2) breath test. Sampling methods and the influence of dietary fibre on fasting level. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985;20:1007–1013.

40. Zhong Y., Yin W., Huang C. Study on the expired gas of subjects with lactose intolerance by using H2/13CO2 breath test [in Chinese]. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2002;31:180–183.

41. Metz G., Jenkins D.J., Peters T.J., et al. Breath hydrogen as a diagnostic method for hypolactasia. Lancet. 1975;1:155–157.

42. Lerch M.M., Rieband H.C., Feldberg W. Concordance of indirect methods for the detection of lactose malabsorption in diabetic and nondiabetic subjects. Digestion. 1991;48:81–88.

43. Barillas-Mury C., Solomons N.W. Test-retest reproducibility of hydrogen breath test for lactose maldigestion in preschool children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:281–285.

44. Barillas-Mury C., Solomons N.W. Variance in fasting breath hydrogen concentrations in Guatemalan preschool children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:109–113.

45. Solomons N.W., Barillas C. The cut-off criterion for a positive hydrogen breath test in children: a reappraisal. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:920–925.

46. Tormo R., Bertaccini A., Conde M., et al. Methane and hydrogen exhalation in normal children and in lactose malabsorption. Early Hum Dev. 2001;65(suppl):S165–S172.

47. Vernia P., Camillo M.D., Marinaro V. Effect of predominant methanogenic flora on the outcome of lactose breath test in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:1116–1119.

48. Montes R.G., Saavedra J.M., Perman J.A. Relationship between methane production and breath hydrogen excretion in lactose-malabsorbing individuals. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:445–448.

49. Bond J.H., Levitt M.D. Quantitative measurement of lactose absorption. Gastroenterol. 1976;70:1058–1062.

50. Robb T.A., Davidson G.P. Two-hour lactose breath hydrogen test. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:481–482.

51. Levitt M.D. Production and excretion of hydrogen gas in man. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:122–127.

52. Newcomer A.D. Screening tests for carbohydrate malabsorption. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1984;3:6–8.

53. Jain N.K., Patel V.P., Pitchumoni C.S. Efficacy of activated charcoal (AC) in reducing intestinal gas: a double blind clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:532–535.

54. Hamilton L.H. Breath tests and gastroenterology. Milwaukee: QuinTron Instruments Company; 1998.

55. Cloarec D., Bornet F., Gouilloud S., et al. Breath hydrogen response to lactulose in healthy subjects: relationship to methane producing status. Gut. 1990;31:300–304.

56. Fritz M., Siebert G., Kasper H. Dose dependence of breath hydrogen and methane in healthy volunteers after ingestion of a commercial disaccharide mixture. Palatini. Br J Nutr. 1985;54:389–400.

57. Behall K.M., Scholfield D.J., van der Sluijs A.M. Breath hydrogen and methane expiration in men and women after oat extract consumption. J Nutr. 1998;128:79–84.

58. Behall K.M., Howe J.C. Breath-hydrogen production and amylose content of the diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1783–1789.

59. Kondo T., Nakae Y. Breath hydrogen and methane excretion produced by commercial beverages containing dietary fiber. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:654–658.

60. Rosenthal A., Solomons N.W. Time-course of cigarette smoke contamination of clinical hydrogen breath-analysis tests. Clin Chem. 1983;29:1980–1981.

61. Solomons N. Evaluation of carbohydrate absorption: the hydrogen breath test in clinical practice. Clin Nutr J. 1984;3:71–78.

62. Gilat T., Ben Hur H., Gelman-Malachi E., et al. Alterations of the colonic flora and their effect on the hydrogen breath test. Gut. 1978;19:602–605.

63. Solomons N.W., Garcia R., Schneider R., et al. H2 breath tests during diarrhea. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1979;68:171–172.

64. Vogelsang H., Ferenci P., Frotz S., et al. Acidic colonic microclimate—possible reason for false negative hydrogen breath tests. Gut. 1988;29:21–26.

65. Perman J.A., Modler S., Olson A.C. Role of pH in production of hydrogen from carbohydrates by colonic bacterial flora: studies in vivo and in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:643–650.

66. Kerlin P., Wong L. Breath hydrogen testing in bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine. Gastroenterol. 1988;95:982–988.

67. Romagnuolo J., Schiller D., Bailey R.J. Using breath tests wisely in a gastroenterology practice: an evidence-based review of indications and pitfalls in interpretation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1113–1126.

68. Perman J.A., Modler S. Glycoproteins as substrates for production of hydrogen and methane by colonic bacterial flora. Gastroenterol. 1982;83:388–393.

69. Kerlin P., Wong L. Lactose tolerance despite hypolactasia in adult celiac disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1987;2:233–237.

70. Matthews S.B., Waud J.P., Roberts A.G. Systemic lactose intolerance: a new perspective on an old problem. Postgraduate Med J. 2005;81:167–173.

71. Waud J.P., Matthews S.B., Campbell A.K. Measurement of breath hydrogen and methane, together with lactase genotype, defines the current best practice for investigation of lactose sensitivity. Ann Clin Biochem. 2008;45:50–58.