7 Laceration Repair

In repairing skin, it is helpful to understand the three phases of wound healing:

Supplies and Equipment

-inch needle holder; curved or straight Iris scissors; one mosquito hemostat; suture scissors; Adson forceps with teeth; skin hooks (optional).

-inch needle holder; curved or straight Iris scissors; one mosquito hemostat; suture scissors; Adson forceps with teeth; skin hooks (optional).Preprocedure Patient Preparation

The patient should be informed of the nature of his or her lacerations. If the laceration is in a cosmetically important area, consider offering the option of a specialist, such as a plastic surgeon or ophthalmologist, for the repair. Advise the patient about the risks of pain, bleeding, dehiscence, infection, and scarring. Inform the patient that most repairs cause some permanent scarring, although attempts will be made to optimize the appearance. Warn patients of the risks of hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, hypertrophic scars, keloids, nerve damage, alopecia, and distortion of the original anatomy. After a discussion of risks and benefits have the patient sign a consent form before beginning the procedure (see Chapter 1, Preoperative Preparation).

Initial Assessment

The initial evaluation before anesthesia should include a history of how the wound was sustained, factors that might impair healing, tetanus immunization history, and an assessment of peripheral neurovascular status. See Table 7-1 for essentials of wound assessment. The clinician should consider the possibility of domestic violence in patients with traumatic wounds, especially if lacerations appear on the face or if multiple injuries of varying ages are noted.

|

Parameters |

Factors to Consider |

|---|---|

| Mechanism of injury | Sharp vs. blunt trauma, bite |

| Dirty vs. clean | Outdoors vs. kitchen sink |

| Time since injury | Suture up to 12 h; 24 h on face |

| Foreign body | Explore and obtain radiograph for metal or glass |

| Functional examination | Neurovascular, muscular, tendons |

| Need for prophylactic antibiotics | If needed, give ASAP and cover Staphylococcus aureus; irrigate well |

In general, antibiotics are not needed for either wound or subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) prophylaxis for cutaneous procedures1 (see Chapter 1). Consideration should be given to coverage for Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA infection in several situations.

The following are major goals for prescribing antibiotics before or after skin surgery:

The recommendations of the American Heart Association (AHA) for the prevention of bacterial endocarditis were last published in 2007 and are discussed in Chapter 1.1 Endocarditis prophylaxis is not needed for incision or biopsy of surgically scrubbed noninfected skin no matter what endocarditis risk factors are present. The 2007 guidelines state that antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for procedures on infected skin and skin structures for patients with underlying cardiac conditions associated with the highest risk of adverse outcome from infective endocarditis (see Chapter 1, Box 1-2 and Table 1-3).1

Cummings et al. performed a meta-analysis of randomized studies on the use of antibiotics to prevent infection of simple wounds.2 They concluded that there is no evidence in published trials that prophylactic antibiotics offer protection against infection of nonbite wounds in patients treated in emergency departments. However, prophylactic antibiotics did reduce the incidence of infection in patients with dog-bite wounds in another meta-analysis.3 The authors concluded that it may be reasonable to limit prophylactic antibiotics to patients with dog-bite wounds that are at highest risk for infection.3

Local and Regional Anesthesia

In traumatic wounds, neurovascular integrity should be assessed prior to administration of anesthesia. The wound should then be fully anesthetized to allow for painless examination of the tissue damage, thorough irrigation, and adequate closure. Many wounds can be adequately anesthetized with 1% or 2% lidocaine. Consider using lidocaine with epinephrine to provide increased hemostasis if there are no contraindications to epinephrine use in the patient, the location, or the wound itself (see Chapter 3, Anesthesia). Topical anesthetics are effective for wounds that do not involve mucosal surfaces. A combination of lidocaine, epinephrine, and tetracaine (LET) applied with a saturated cotton ball or as a gel formulation directly into the wound provides adequate anesthesia for many wounds.4,5

Regional anesthesia may be desirable in cases where the volume of locally infiltrated anesthesia might exceed the safe maximum dosage (see Chapter 3, Table 3-3) or in cosmetically important areas where a local infiltration might distort the anatomy to impair a meticulous closure. If a regional anesthetic technique is employed, lidocaine without epinephrine is the optimal choice, because epinephrine’s role as a vasoconstrictor is not needed at a site remote to the traumatic wound.

Follow these instructions to minimize the pain of injecting local anesthetic:

Wound Preparation

Determine If the Wound Needs Intervention to Close

One study assessed the difference in clinical outcome between lacerations of the hand closed with sutures and those treated conservatively.6 Consecutive patients with uncomplicated lacerations of the hand (full thickness < 2 cm; without tendon, joint, fracture, or nerve complications) who would normally require sutures were randomized to suturing or conservative treatment. The mean time to resume normal activities was the same in both groups (3.4 days). Patients treated conservatively had less pain and treatment time was 14 (10 to 18) minutes shorter. The groups did not differ significantly in the assessment of cosmetic appearance on the visual analogue scale. Conservative treatment was faster and less painful.6

Cleansing

After the wound is anesthetized, cleansing of the wound should be performed by irrigation with normal saline at 8 to 12 psi of pressure. This can be accomplished by attaching an 18-gauge angiocatheter or a commercially available splash shield to a 20- or 30-mL syringe. At least 200 mL of irrigation is recommended. Irrijet and Zerowet were superior to an angiocatheter in preventing splatter during wound model irrigation.3 Zerowet was particularly effective in preventing splatter onto the irrigator’s face (Figure 7-1).3

A multicenter comparison of tap water versus sterile saline for wound irrigation published in 2007 showed equivalent rates of wound infection in immunocompetent patients.7 The tap water group irrigated their own wounds under the water tap for a minimum of 2 minutes after they had the wound anesthetized. Higher risk wounds were excluded from the study, indicating that tap water is a reasonable cleansing alternative for low-risk lacerations. In one randomized clinical trial, warmed saline was more comfortable and soothing than room-temperature saline as a wound irrigant among patients with linear lacerations.8

Closure Technique

Ideally, four principles should be incorporated in the process of closing any wound:

Choice of Sutures

Most lacerations will be closed with nylon. If a two-layer closure is needed, an absorbable suture such as polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) or a synthetic absorbable monofilament suture is a good choice for the deep layer. Silk sutures may be considered for closure in the mouth or other areas where the nylon ends will be bothersome. Alternately, rapidly absorbing Vicryl Rapide may be used in oral lacerations without the need for suture removal. In one study, otherwise healthy children with facial lacerations were randomized to repair using fast-absorbing catgut or nylon suture.9 There were no significant differences in the rates of infection, wound dehiscence, keloid formation, and parental satisfaction between the absorbable catgut and the nylon suture.9 Fast-absorbing catgut suture is not as easy to work with as nylon but does have the advantage of not requiring suture removal in children who may be very fearful of the suture removal process.

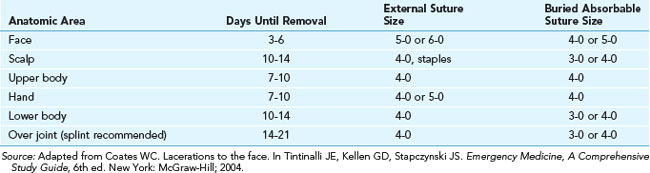

Suggested suture size and time of removal based on anatomic areas is found in Table 7-2.

Sutured Repairs

Lacerations are approximated with sutures using a variety of techniques (see Chapter 6, Suturing Techniques), as discussed in the following subsections.

Simple Interrupted Suture

On completion of a simple interrupted suture (Figure 7-2), the skin margins should be slightly everted. The needle should enter the skin surface at a 90-degree angle. The stitch should be as wide as it is deep. The suture on both sides of the wound should be equal distance from the wound margin and of equal depth. The final shape should appear like that of a pear (see Chapter 6, Figure 6-5). As a general rule, these sutures need to be no closer than 2 mm in a fine plastic closure and can be substantially farther apart in other types of closures. The distance between sutures should equal half the total distance of the sutures across the incision. The finer the suture, the closer the stitch needs to be. Avoid tying the knots too tightly. The knots should be lined up on the same side of the wound, usually the one with the best blood supply or least interference with comfort (e.g., away from eyelid).

Simple Running Stitch

The advantages of the simple running stitch (Figure 7-3) in sterile wounds under little or no tension are that it is quick, it distributes tension evenly, and it provides excellent cosmetic results. If there is significant gaping of the wound, interrupted suture methods should be used. Because the risk of contamination is increased with traumatic lacerations, the simple running stitch is less desirable in these wounds. In case of infection, the entire wound closure would need to be removed. The relative disadvantage of removing the entire stitch at one time also poses a problem in wounds under some increased tension. With interrupted techniques, some sutures may be removed early for better cosmesis, whereas a few remaining ones can be left for prevention of dehiscence and removed at a later date. The simple running stitch is ideal in the scalp and is often used in elliptical excision repairs.

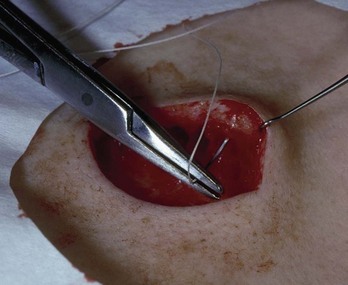

Deep Suture with Inverted Knot or Buried Stitch

Deeper wounds or wounds under tension are best closed by providing structural support and not relying solely on nonabsorbable superficial sutures. Well-placed deep absorbable sutures (Figure 7-4 and Chapter 6, Figure 6-9) can do much to aid in closing a wound, remove tension from the superficial skin sutures, and decrease scarring by providing increased wound support long after the epidermal sutures have been removed. Deep sutures also close dead space, which decreases the risk of hematomas and dehiscence.

The inverted knot technique places the knot as far below the skin margins as possible to avoid suture spitting (migration of deep sutures to the skin surface). It also keeps the ends of the cut suture from protruding through the wound margin. To start the stitch, begin at the bottom of the wound (in the undermined area if undermining was used) and come up usually just below the epidermal-dermal junction (remember, “Bottoms up!”). Go straight across the incision, enter at the same level at the opposite side, then go down to the base at the same depth once again and tie. Care should be taken to achieve symmetry of depth and width on both sides of the laceration. For a more detailed discussion of the deep vertical mattress suture, see Chapter 6. The epidermis is then fully closed with a closure of choice (nonabsorbable suture, wound closure strips, or tissue adhesive).

Vertical Mattress Suture

The vertical mattress suture (Figure 7-5 and Chapter 6, Figure 6-12) promotes eversion of the wound edges of the skin. It is also useful when the natural tendency of loose skin is to create inversion of the wound margins, which should be avoided. A good example is the loose, flabby skin under the triceps muscle and thin skin in older people. The stitch is also appropriate when the skin is very thin and interrupted sutures have a tendency to pull through.

Horizontal Mattress Suture

The horizontal mattress suture (see Chapter 6, Figure 6-13) is helpful in wounds under a moderate amount of tension and also promotes wound edge eversion. It is especially useful on the palms or soles and in patients who are poor candidates for deep sutures because of susceptibility to wound infections. It is not recommended in wounds that are located in cosmetically important areas.

Subcuticular Running Suture (Figure 7-6 and Chapter 6, Figure 6-17)

The subcuticular running suture (Figure 7-6 and Chapter 6, Figure 6-17) is used to close linear wounds that are under minimal tension; it yields an excellent cosmetic result. It is advantageous in patients who tend to form hypertrophic scars or keloids, because it minimizes the number of times the skin’s surface must be perforated with the suture needle. Meticulous alignment of each stitch is critical to prevent gaps in the linear wound. The ends of the suture do not need to be tied; taping under slight tension preserves approximation. If desired, the two ends can be tied over the wound, or a knot can be placed at each end to prevent slippage. Usually a polypropylene-coated nylon works best. Steri-Strips, strips, or tissue glue can be used to supplement this type of stitch. Special care must be taken to avoid pressure on the wound, since this stitch separates easily.

Three-Point or Half-Buried Mattress Suture (Chapter 6, Figure 6-15)

The three-point or half-buried mattress suture (see Chapter 6, Figure 6-15) is designed to permit closure of the acute corner tip of a laceration without impairing blood flow to the tip. It is an intradermal stitch in which the needle is inserted initially into the intact skin on the nonflap portion of the wound and passed through the skin at the mid-dermis level; at the same level, the suture is then passed transversely through the tip of the flap, returned on the opposite side of the wound, and brought through the skin, paralleling the point of entrance. The suture is tied by drawing the tip snugly into place in good approximation. Care should be taken not to have the knot tied over the point of the flap. This same approach can be used in closing a stellate laceration, drawing the tips together in a purse-string fashion. The resulting knot should be placed over the segment of the stellate laceration with the best blood supply. Repair of a “T” laceration also uses this technique.

Surgical Adhesive Strips (Steri-Strips)

Surgical adhesive strips may be used alone for small, superficial wounds (especially in young children).10,11 When these strips suffice to close a wound, they are more easily placed without physical or psychological trauma to the child. Wounds closed with adhesive strips are more resistant to infection than are sutured wounds. However, surgical adhesive strips are not appropriate for deep lacerations because they do not provide adequate deep-tissue approximation or skin-edge eversion when used alone. Surgical adhesive strips with or without gum mastic did not provide any additional strength to wounds closed by subcuticular continuous suture.12 Surgical adhesive strips are especially helpful after suture removal to prevent dehiscence and may be left on until they fall off. Patients may shower with them on after the initial 24 hours.

Surgical adhesive strips adhere better to the skin when a sticky substance is applied to the skin first. Tincture of benzoin and gum mastic (Mastisol) are both helpful. Studies have shown that gum mastic offers superior adhesive qualities compared with benzoin and has a lower incidence of postoperative contact dermatitis and subsequent skin discoloration.13,14

Tissue Adhesives

Tissue adhesives may be used to close certain wounds that are not under any tension and are not at risk for infection. These can be purchased as octylcyanoacrylate (Dermabond) and butylcyanoacrylate (SkinStitch). A Cochrane systematic review provides evidence that tissue adhesives are an option to sutures, staples, and adhesive strips for the management of simple traumatic lacerations that are not under tension nor prone to wound infection.15 Overall, no significant differences were found in cosmetic scores at the reported assessment periods between tissue adhesives and these other methods. At 1 to 3 months, a subgroup analysis significantly favored butylcyanoacrylate over all other skin closure methods. Tissue adhesives significantly lowered the time to complete the procedure, the levels of pain, and the incidence of erythema. However, the data revealed a significant increase in the rate of dehiscence with the use of tissue adhesives when compared with the other methods of skin closure.16

Tissue adhesives and surgical adhesive strips are both excellent “no needle” alternatives for the closure of suitable pediatric lacerations.10 These two techniques are similar in efficacy, parental acceptability, and cosmetic outcome.10 Appropriate wound preparation techniques, such as irrigation under local or topical anesthesia, are still necessary. Nail bed repair performed using tissue adhesives is significantly faster than suture repair.17 Tissue adhesives provide similar cosmetic and functional results in the management of acute nail bed lacerations.17

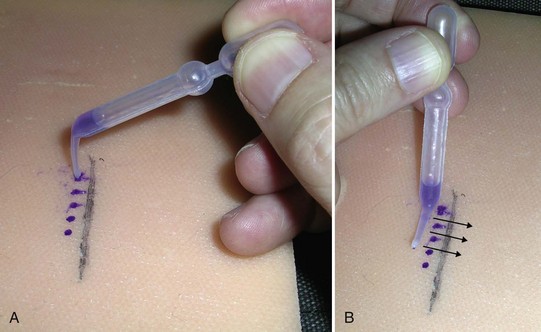

Follow these guidelines, which are adapted from SkinStitch information, when using tissue adhesives (Figure 7-7):

Staples

Staples are most often used to repair scalp lacerations. In one randomized trial of children (ages 1 to 16 years) with simple scalp lacerations, patients were randomly assigned to either a stapling or suturing procedure.18 Procedure time was significantly lower in the stapling group (P = 0.001). There were no significant differences in the final follow-up cosmetic score between the two groups.18 Although staples are faster to apply to the scalp, the cost of the materials is greater. Scalp stapling should not be attempted in men who are already bald or in wounds that extend to the forehead.

Delayed Primary Closure (Tertiary Intention)

Delayed primary closure is healing by tertiary intention. This technique is used for wounds that are greater than 12 hours old (24 hours for facial lacerations) but would cosmetically benefit from closure in a few days. After anesthetizing, evaluating, and irrigating the wound, insert a small piece of petroleum gauze between the wound edges and place the patient on an antibiotic, such as cephalexin, for 5 days. On the third day, the patient should return for definitive repair. If the wound appears clean and free of infection and has not started the granulation process, the repair can proceed. The wound is reanesthetized, reirrigated, and closed primarily with nonabsorbable sutures (i.e., no deep sutures because they increase the chance of infection). The patient continues the course of prescribed antibiotics and suture removal occurs at the interval beginning at the time of suturing (Table 7-2).

Complications

The complications of laceration repair are the same as when a biopsy or surgical excision is performed (bleeding, infection, dehiscence, etc.). The main differences relate to coexisting trauma such as crush injuries that can devitalize tissue around the laceration or lead to underlying injuries to tendons, vessels, bones, or joints. For discussion of complications and their treatment and prevention see Chapter 36, Complications.

Postprocedure Patient Education

Moist healing (application of petrolatum after gentle washing twice daily) aids in quicker healing. Although antibiotic ointments were traditionally used for dressings postsurgically, Smack et al. determined that clean wounds heal just as well when white petrolatum is applied.19 Neomycin and bacitracin are frequent contact allergens and have not been proven to prevent infections after a laceration is repaired. Application of any of these products should be limited to the smallest possible area over the suture line. Extension over the wound edges may lead to maceration of the skin and reduce its ability to hold the sutures securely in place, thus causing them to pull through and lead to wound dehiscence.

Suggestions for the timing for skin suture removal are listed in Table 7-2.

Considerations for Specific Anatomic Repairs

Lip

For lip lacerations that extend through multiple layers, a more complex repair must be performed. A through-and-through laceration is repaired in three steps. After ensuring the integrity of the teeth, the mucosal layer is gently irrigated and closed with a soft suture for comfort (4-0 silk or Vicryl Rapide). Next, the wound is reirrigated from the outside and the muscle layer closed with an absorbable suture. Finally, the skin is closed with simple interrupted sutures. It is reasonable to consider an infraorbital regional nerve block for an upper lip laceration or a mandibular regional nerve block for a lower lip laceration (see Chapter 3).

Eyelid

For an uncomplicated lid laceration, a small (6-0) suture is used. Care must be taken to place the suture through the skin only and to avoid penetration through the tarsal plate or globe (Figure 7-6). Regional anesthesia with a supraorbital nerve block for the upper lid or an infraorbital nerve block for the lower lid may be useful (see Chapter 3).

CPT/Billing Codes and ICD-9-CM Diagnostic Codes

Conclusion

In the treatment of lacerations, careful inspection, adequate irrigation, skilled closure, and appropriate wound care can produce the best functional and cosmetic results. See Box 7-1 for a list of suturing pearls for lacerations. The principles and steps covered in this chapter show how lacerations can be repaired with maximal skill and minimal discomfort to the patient.

Box 7-1 Suturing Pearls for Lacerations

Resources

The remainder of the equipment can be obtained from any medical supplier, including those listed in Chapter 2.

1. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group 3. Circulation. 2007;116:1736-1754.

2. Cummings P, Del Beccaro MA. Antibiotics to prevent infection of simple wounds: a meta-analysis of randomized studies. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:396-400.

3. Cummings P. Antibiotics to prevent infection in patients with dog bite wounds: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:535-540.

4. Adler AJ, Dubinisky I, Eisen J. Does the use of topical lidocaine, epinephrine, and tetracaine solution provide sufficient anesthesia for laceration repair? Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:108-112.

5. Resch K, Schilling C, Borchert BD, et al. Topical anesthesia for pediatric lacerations: a randomized trial of lidocaine-epinephrine-tetracaine solution versus gel. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:693-697.

6. Quinn J, Cummings S, Callaham M, Sellers K. Suturing versus conservative management of lacerations of the hand: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2002;325:299.

7. Moscati RM, Mayrose J, Reardon RF, et al. A multicenter comparison of tap water versus sterile saline for wound irrigation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:404-409.

8. Ernst AA, Gershoff L, Miller P, et al. Warmed versus room temperature saline for laceration irrigation: a randomized clinical trial. South Med J. 2003;96:436-439.

9. Luck RP, Flood R, Eyal D, et al. Cosmetic outcomes of absorbable versus nonabsorbable sutures in pediatric facial lacerations. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:137-142.

10. Mattick A, Clegg G, Beattie T, Ahmad T. A randomised, controlled trial comparing a tissue adhesive (2-octylcyanoacrylate) with adhesive strips (Steristrips) for paediatric laceration repair. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:405-407.

11. Zempsky WT, Parrotti D, Grem C, Nichols J. Randomized controlled comparison of cosmetic outcomes of simple facial lacerations closed with Steri-Strip skin closures or Dermabond tissue adhesive. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:519-524.

12. Yavuzer R, Kelly C, Durrani N, et al. Reinforcement of subcuticular continuous suture closure with surgical adhesive strips and gum mastic: is there any additional strength provided? Am J Surg. 2005;189:315-318.

13. Mikhail GR, Selak L, Salo S. Reinforcement of surgical adhesive strips. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:904-905. 908

14. Lesesne CB. The postoperative use of wound adhesives. Gum mastic versus benzoin, USP. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:990.

15. Farion K, Osmond MH, Hartling L, et al. Tissue adhesives for traumatic lacerations in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;CD003326.

16. Beam JW. Tissue adhesives for simple traumatic lacerations. J Athl Train. 2008;43:222-224.

17. Strauss EJ, Weil WM, Jordan C, Paksima N. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of 2-octylcyanoacrylate versus suture repair for nail bed injuries. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2008;33:250-253.

18. Khan AN, Dayan PS, Miller S, et al. Cosmetic outcome of scalp wound closure with staples in the pediatric emergency department: a prospective, randomized trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:171-173.

19. Smack DP, Harrington AC, Dunn C, et al. Infection and allergy incidence in ambulatory surgery patients using white petrolatum vs bacitracin ointment. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:972-977.

apart and next to the area to be covered. These small drops will prevent running and when spread will create thin coats and dry in about 30 minutes. (B) Then, twirl the applicator and use the spreader to spread the drops.

apart and next to the area to be covered. These small drops will prevent running and when spread will create thin coats and dry in about 30 minutes. (B) Then, twirl the applicator and use the spreader to spread the drops.