14 Labour

Labour

Features of labour

Mechanical features of labour

There are three mechanical features of labour commonly described:

1. The powers: this is the uterine force of contractions that will expel the fetus. In labour an efficient uterus will contract regularly for 40–60 seconds every 2–3 minutes. These contractions will cause descent of the presenting fetal part, allowing effacement and subsequent dilatation of the cervix. By definition, the nulliparous uterus is inefficient, in that the uterus often contracts irregularly, as opposed to the multiparous uterus.

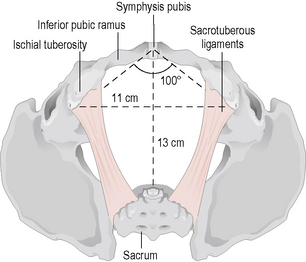

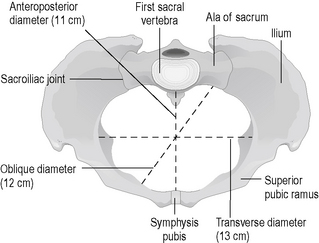

2. The passage: the bony pelvic canal has to be traversed by the fetus in labour and, therefore, the diameters of the pelvis need consideration (Figs 14.1 and 14.2). The pelvic inlet has two diameters:

Figure 14.1 Diameters of the pelvis, the pelvic brim.

(Redrawn with permission from Rymer J, Davis G, Rodin A et al. 2003 Preparation and Revision for the DRCOG, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, p. 382.)

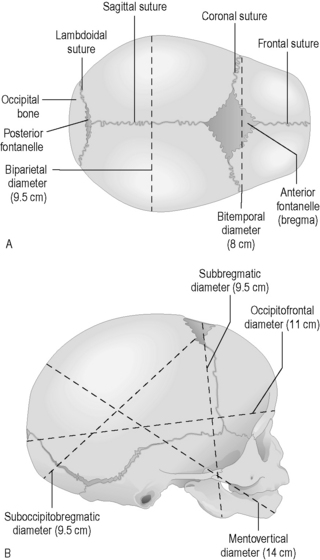

3. The passenger is the fetus and the fetal head diameters (Fig. 14.3) are important to allow ease of descent:

Mechanical features of the vertex in labour

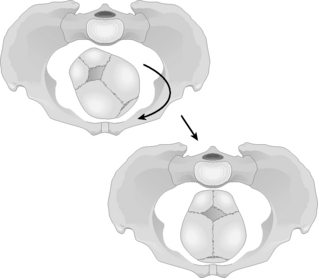

The mechanics of labour described above cause changes in the attitude of the fetal head during descent into the pelvis (Fig. 14.4) and are summarized in stages as:

1. Descent: the fetal head often descends during the last few weeks of pregnancy in the nulliparous patient, but this descent may not occur until just before the onset of labour in multiparous patients or also in Afro-Caribbean women because of the shape of their pelvises.

2. Engagement: this occurs when the maximum diameter of the fetal head has passed through the pelvic inlet. It is usually described in fifths of the fetal head that can be palpated abdominally, with engagement being defined as less than or equal to two-fifths of the fetal head palpable above the pelvic brim.

3. Flexion: the fetal head flexes as it descends through the pelvis in order to allow its smallest diameter to traverse the pelvis. With maximum flexion the posterior fontanelle can be easily palpated vaginally.

4. Internal rotation: as the fetal head descends it rotates from a LOT position to OA, as described above (Fig. 14.5).

5. Extension: the fetal head remains flexed until it reaches the perineum and then begins to extend as the head crowns as it is about to be delivered.

6. External rotation (restitution): as the fetal head is delivered it reverts to the transverse position (OT).

7. Lateral flexion: when the head is delivering the anterior shoulder appears, followed by the posterior shoulder with the trunk delivering by lateral flexion.

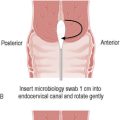

Assessment of labour

1. History: the history on admission should include specific questioning on the following:

Management

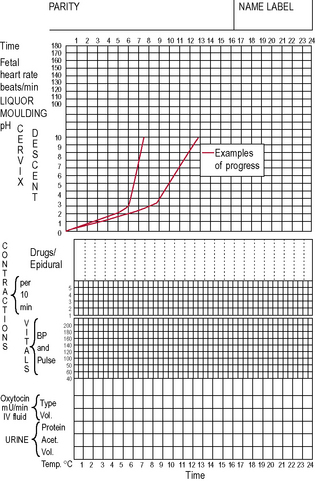

Once the diagnosis of labour has been made then the membranes can be ruptured to assess the liquor for the presence of meconium, which will provide information on fetal well-being. A partogram is a visual record of labour progress and records a variable amount of information depending on each individual obstetric unit. The following is a list of usual information recorded in a partogram (Fig. 14.6):

2. The date and time of admission

4. A progressive representation of cervical dilatation (descent of the head). The partogram may include an action line denoting a minimum acceptable rate of cervical dilatation (usually 1 cm/h for a primigravid patient). If progress falls below the action line, then medical intervention may be considered

5. Details on the contractions should include frequency (usually described as the number occurring in 10 minutes), duration and strength

6. The fetal heart rate by intermittent auscultation or continuous fetal monitoring

7. Colour of liquor and time of rupture of membranes

8. Drugs given, including oxytocin and analgesics

9. Maternal urine production and urinalysis for ketones and/or protein.

Progress of labour

Primiparous labour

Labour should proceed at a rate of at least 1 cm cervical dilatation per hour in a primiparous patient. The first stage should, therefore, last for 10 hours with 2 hours for the second stage. Labour that lasts for longer than 12 hours is said to be prolonged. However, the primiparous uterus is notoriously inefficient as it has not experienced labour before, so that even if the contractions feel strong and frequent they may be having little effect on cervical dilatation. This is correctable if diagnosed early by performing an amniotomy if the membranes are still intact and by commencing an oxytocin infusion to augment labour. Careful clinical monitoring is required to ensure that contractions do not exceed one every 2 minutes or hypertonia results, with fetal hypoxia caused by restriction of the maternal placental blood flow. Oxytocin is, therefore, administered by titrating the infusion against the uterine contractions to achieve efficient uterine action and each obstetric unit will have protocols for concentration and infusion rates (Fig. 14.6). If full dilatation is not foreseeable within 12 hours, then caesarean section may need to be considered as the woman will become exhausted and there will be increasing risk of fetal hypoxia. The partogram is a crucial guide to labour progression. An individual decision is taken by each woman on the recommendation of the obstetrician and midwife.

Fetal surveillance in labour

Methods

1. Amniotic fluid and liquor: the absence of liquor is associated with intrauterine growth retardation. Meconium is the passage of stool by the fetus in utero and is caused by vagal stimulation of the gut as a result of an episode of hypoxia. Some units will grade the meconium during labour from 1 to 3. Grade 1 meconium is lightly stained fluid (meconium that is very diluted by adequate liquor), grade 2 is moderately stained and grade 3 is a heavy, thick liquid associated with the fresh passage of meconium in the presence of reduced liquor, which is of particular concern, indicating fetal hypoxia.

2. Intermittent auscultation with either a Pinard’s stethoscope or a Sonicaid. This is sometimes the method of choice in monitoring a low-risk labour and should be performed for 1 minute after a contraction and every 15 minutes to detect accelerations or decelerations of the fetal heart rate.

3. Continuous fetal monitoring using either an abdominal transducer (as part of the CTG) or a fetal scalp electrode. This will give a continuous real-time record of the fetal heart rate response to labour. The CTG should always be interpreted as part of the whole clinical picture, including stage of labour, maternal analgesia and status of the uterine contractions.

4. Fetal blood sampling is performed when the CTG suggests fetal compromise in labour and is interpreted on the basis of the fetal blood pH. A pH of greater than 7.25 is considered normal; a pH of between 7.20 and 7.25 is a borderline result that will need to be repeated within 1 hour; and a pH of less than 7.20 is abnormal, indicating immediate delivery.

Fetal heart rate patterns

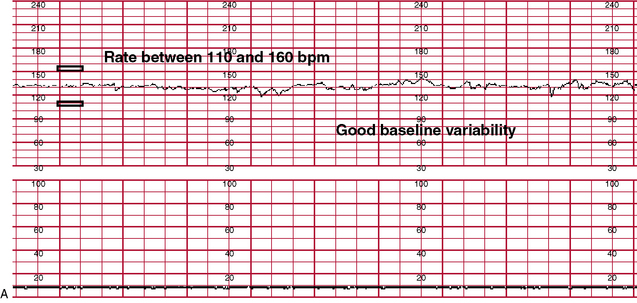

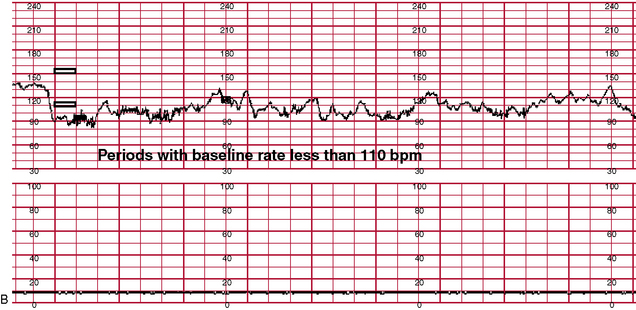

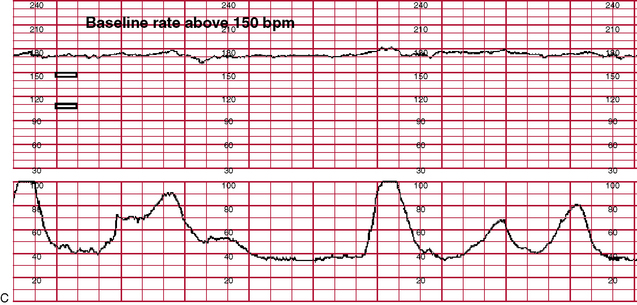

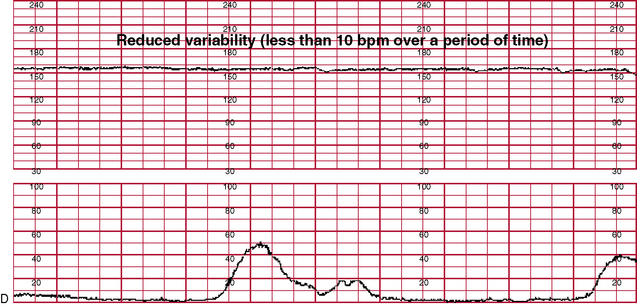

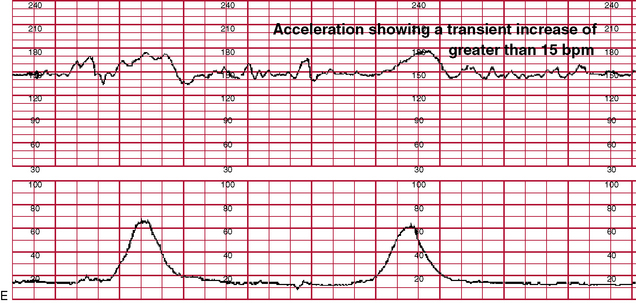

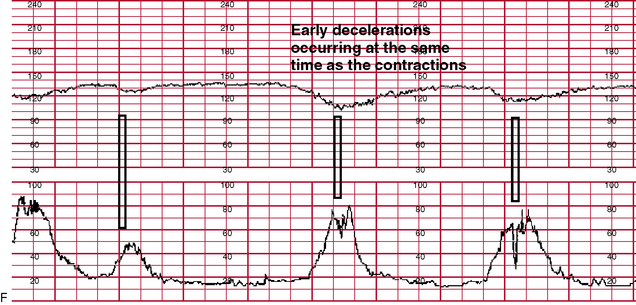

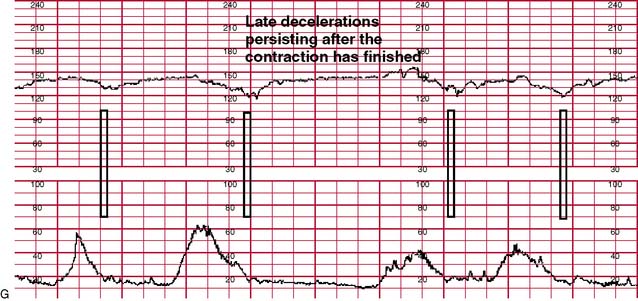

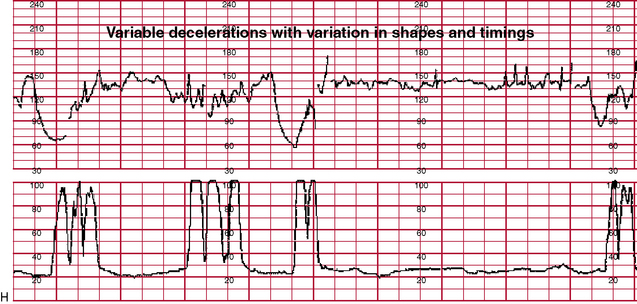

There are three features of the fetal heart rate that should be noted – the baseline, beat-to-beat variability and the presence of accelerations or decelerations (see Fig. 14.7 for examples of CTG traces):

• Normal: the normal baseline should be between 110 and 160 beats per minute (bpm). Baseline beat-to-beat variability should be 5–25 bpm. Accelerations from baseline of 10–15 bpm will indicate a healthy fetus.

• Baseline tachycardia: a baseline fetal heart rate of greater than 160 bpm can be associated with prematurity, hypoxia, maternal pyrexia or drugs and fetal distress if also in the presence of any other abnormality.

• Baseline bradycardia: a baseline fetal heart rate of less than 110 bpm may be associated with postmaturity, hypoxia or heart block. A baseline of less than 90 bpm is usually indicative of impending fetal demise.

• Baseline variability: variability is the presence of irregular accelerations from baseline, and loss of beat-to-beat variability can indicate a sleep pattern if it lasts for less than 40 minutes. If it is prolonged beyond this it indicates hypoxia. Increase in variability may also indicate acute hypoxia.

• Early decelerations: these occur with the onset of a contraction and the fetal heart rate returns to baseline by the end of the contraction. These are usually caused by fetal head compression during descent and are benign.

• Late decelerations: these occur when the fetal heart rate drops after the peak of the contraction, with slow recovery to baseline after the contraction. Late decelerations are associated with fetal hypoxia.

• Variable decelerations: these decelerations, as the name suggests, occur at variable times during labour, often with no association to the contraction, and usually indicate cord compression.

Cephalic malpositions

1. OP: this is the commonest malposition and is caused by a posterior rotation of the fetal head during descent and results in deflexion of the fetal head and thus a larger head diameter traversing the pelvis so that obstruction is caused. It is associated with inefficient uterine action, pelvic shape variants and epidurals. This malposition may be corrected as labour progresses spontaneously or with an oxytocin infusion if the contractions are poor. The earlier slow progress is diagnosed as being caused by an OP presentation, the better the chance there is of rotation to OA. However, the fetus may be delivered in that position (face to pubis) spontaneously if the pelvic diameters are adequate, but an instrumental delivery may be required to rotate the fetal head to OA or to deliver face to pubis.

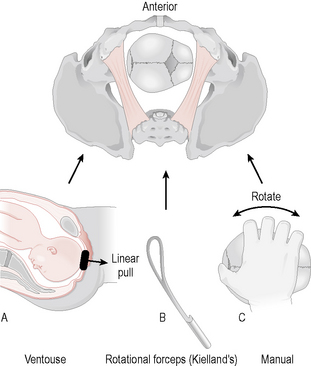

2. OT: again this is caused by incomplete rotation of the fetal head during labour. If this position persists in the second stage, then delivery will not occur unless rotated to OA manually or with Kielland forceps or the ventouse. Both OP and OT instrumental deliveries are increasingly being performed in theatre, with early recourse to caesarean section if required.

3. Brow presentation: this is caused by hyperextension of the fetal neck in labour and is generally incompatible with a vaginal delivery (may deliver if fetus is preterm) as the presenting diameter is too large (mento-vertex diameter is usually 13 cm), and a caesarean delivery is indicated unless flexion occurs during the course of labour.

4. Face presentation: this is the result of complete extension of the fetal neck. The facial features can be felt on vaginal examination and vaginal delivery may be possible if the chin is anterior (mento-anterior) as it will catch on the pubic bone during descent in the pelvis, causing the fetal neck to flex and, therefore, allow for further rotation. If the chin is posterior (mento-posterior), flexion is impossible and caesarean section is indicated.

Induction of labour

Indication

1. The risk to mother and fetus if the pregnancy were allowed to continue

2. The risk to the mother of complications of induction and to the fetus of prematurity.

Common reasons for induction include:

• Postmaturity: when pregnancy extends beyond the due date, as studies have demonstrated an increase in perinatal mortality with increasing postmaturity as a result of decreased placental function. The time frame for this varies between units, but is usually at 41–42 weeks (despite the definition of term being until 42 weeks)

Contraindications are defined as the following:

• Absolute: acute fetal compromise, unstable lie (if the lie stabilizes to cephalic, then controlled artificial rupture of the membranes (ARM) may be performed), placenta praevia and pelvic obstruction.

• Relative: previous caesarean section (although there are differing opinions in this situation), breech presentation and prematurity.

Method

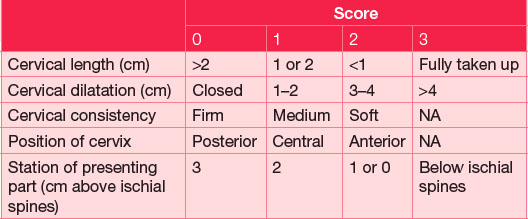

The method of induction will usually depend on the cervical assessment, which will normally be undertaken at the time of the decision to induce (Table 14.1):

• Medical: insertion of prostaglandin gel or pessaries into the posterior vaginal fornix. Particular care should be exercised when using prostaglandins in a multiparous woman or a woman with a uterine scar, because of the risk of overstimulation. All prostaglandin administrations should be followed by a CTG for a minimum recording of 1 hour. Usually, following the second dose of prostaglandin, labour will start spontaneously. Alternatively, the cervix will have ripened sufficiently to allow surgical induction to proceed.

• Surgical induction of labour (ARM): if the cervix is favourable (Bishop’s score of >7) (Table 14.1), or the hindwaters are ruptured, there is no advantage in further use of prostaglandin. A vaginal examination should reveal the presence of fetal membranes in advance of the fetal head, and ARM can be performed using an amnihook.

• Following ARM multiparae may go into labour spontaneously as prostaglandins are released as the membranes rupture. To reduce unnecessary venous cannulation they may be left to mobilize for 2–4 hours to allow spontaneous contractions to begin. This will rarely be effective in primiparae and, therefore, an oxytocin infusion should be commenced immediately. The oxytocin regime for induction of labour is the same as that used for augmentation.

Operative delivery

Criteria for operative vaginal delivery

• Patient understands and accepts the need for intervention.

• There is a valid indication for expediting delivery.

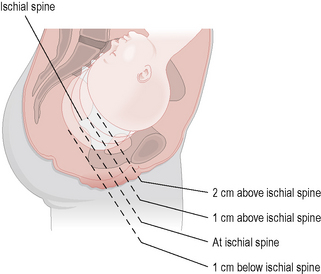

• Fetus must be in a cephalic presentation and the head not palpable above the pelvic brim (the exception being the use of forceps to aid delivery of the aftercoming head in vaginal breech delivery). On vaginal examination the head must be at or below the level of the ischial spines.

• Cervix must be fully dilated and the membranes ruptured.

• Maternal bladder should be empty.

• There should be no excessive moulding or caput, and the operator must be certain of the position of the fetal head.

Forceps

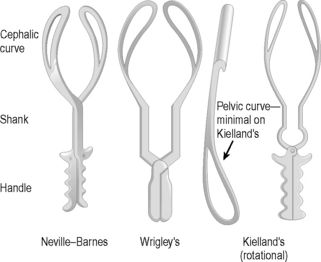

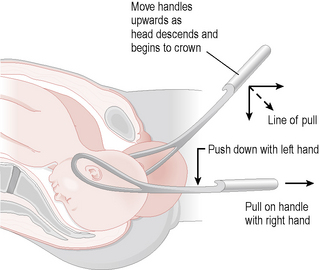

The two blades of an obstetric forceps fit around the sides of the fetal head and should easily come together when correctly applied. Non-rotational forceps (e.g. Neville–Barnes, Simpson’s or Wrigley’s) have a cephalic curve for the head and a pelvic curve to follow the contours of the sacral hollow. Rotational forceps (e.g. Kielland’s) do not have a pelvic curve to minimize soft-tissue trauma during rotation to the OA position before traction is applied (Figs 14.8 and 14.9).

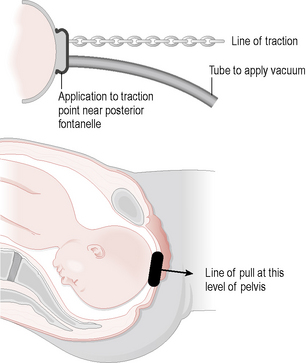

Vacuum extractor (ventouse)

This instrument has either a metal or soft cap connected to a handle and then to a suction device that can be controlled either by a hand or foot release device. The cup must be carefully applied to an optimal point on the fetal head and the position checked before the vacuum is commenced. Traction is applied in the correct direction in combination with maternal effort and rotation can occur to the OA position as the head follows the curve of the pelvis during descent. The soft cup is more popular, but metal cups can be used for more difficult deliveries (Fig. 14.10).

Type of instrumental delivery

• Low cavity: the head is well below the ischial spines and is usually in the OA position.

• Mid cavity: the head is not palpable abdominally and is at or just below the level of the ischial spines. The head may be in the OA position, but is more commonly malpositioned in an OT or OP position, which will require rotation. Often these deliveries should be undertaken in theatre, with early recourse to caesarean section if progressive descent is not immediate.

Caesarean section

Indications

Elective

Management

• Caution regarding induction of labour. If the cervix is favourable, an ARM may be performed with cautious use of oxytocin, but few would consider administering prostaglandins to ripen the cervix.

• Continuous fetal monitoring should be carried out.

• Avoid prolonged labours: failure to progress should alert the obstetrician to consider caesarean section. Women with a previous caesarean section who present in spontaneous labour should not have augmentation for slow progress.

Prelabour rupture of membranes

• Admit patient for observation

• Four-hourly maternal temperature and pulse

• Twice-weekly blood tests for white cell count and C-reactive protein

• Weekly or 2-weekly fetal ultrasound assessment

• Can consider allowing patient home to self-monitor with instruction to return if there are any concerns.

Preterm labour

This is defined as the delivery of a fetus between 24 and 37 completed weeks of pregnancy.

Assessment

A correct diagnosis of labour is just as important in preterm patients:

• History and examination will include precipitating factors and cervical assessment.

• Ensure accurate dating information regarding gestation.

• CTG to assess fetal well-being and uterine activity.

• Ultrasound assessment to confirm fetal well-being, exclude fetal abnormality, estimate fetal weight and confirm presentation.

Management

1. Steroids to promote fetal lung maturity: glucocorticoids administered by injection to the mother 24 hours before delivery have been shown to reduce perinatal mortality and morbidity by promoting lung maturity in babies born between 24 and 34 weeks. There is at present no evidence to suggest that repeated doses are of any benefit.

2. Tocolysis: tocolytics act by inhibiting uterine smooth-muscle contractility. The most common agents used are the beta-sympathomimetics like ritodrine and salbutamol given as an infusion intravenously. This delays rather than stops preterm labour, to allow administered steroids to have an effect or if the mother needs to be transferred due to inadequate neonatal facilities being available. Tocolysis is contraindicated in cases with ruptured membranes or following an antepartum haemorrhage and should be used with caution with careful maternal monitoring as these infusions have significant side effects, including tremor, anxiety, tachycardia and pulmonary oedema.

3. Delivery: adequate neonatal care facilities must be available to ensure optimum outcome, otherwise an in-utero transfer should be arranged. Vaginal delivery is usually recommended for preterm delivery, especially if there is a cephalic presentation. Mode of delivery of a breech presentation is controversial, but again can be safely carried out vaginally in the care of an experienced obstetrician. Instrumental delivery is conducted for the usual reasons, but the ventouse is contraindicated in fetuses of less than 34 weeks’ gestation, because of possible risk of injury to the immature fetal head and intracranial haemorrhage.

Pain relief in labour

Self-help and natural sources (non-pharmacological methods)

• Relaxation: being aware of physical tension and being able to relax consciously both during and between contractions helps to reduce pain.

• Changing position and moving: many women find pelvic rocking and other rhythmic movements help with pain.

• Massage can be a great aid to localized pain in the lower back, hips and thighs.

• Music: this can be both relaxing and a distraction from the pain of contractions.

• Warm baths or showers: many women find warm water very soothing, especially in early labour, and some professionals may advocate the options of a water birth in low-risk pregnancies.

• Natural therapies include acupuncture, aromatherapy, herbal remedies, homeopathy and hypnotherapy and many women find these helpful during labour. A properly qualified practitioner must be consulted.

• Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) consists of a machine which sends small electrical impulses between four electrodes taped to the woman’s back. The woman controls the strength of the impulses by turning a small dial. It reduces pain by interfering with the pain messages to the brain and also by increasing the production of the woman’s endorphins (natural painkillers). Women are advised to start using TENS in early labour as the pain-relieving effect is built up over time.

Pharmacological methods of pain relief

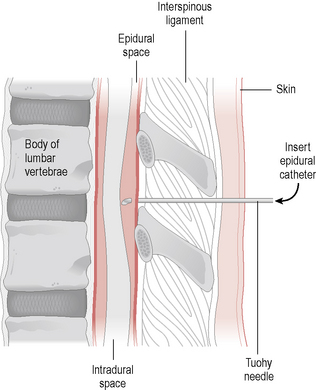

Epidural analgesia provides the most effective form of pain relief in labour and is becoming a more popular choice with most women. The epidural space is the potential space lying outside the dura mater. Injection of local anaesthetic into this space will produce analgesia in the spinal nerve roots (Fig. 14.12). The nerve roots T10–L1 need to be targeted to give adequate analgesia during the first stage of labour and the sacral nerve roots for the second stage. A more extensive block to T8 will be required for caesarean sections. To administer an epidural, an indwelling plastic catheter is introduced into the epidural space (usually at L2–3 or L3–4) through a needle with a curved tip (Tuohy needle). The local anaesthetic usually administered is bupivacaine, but this causes motor blockade so that more often it is given in combination with the opioid fentanyl, to good effect. This mixture is becoming more popular as it can allow the woman limited mobility with effective analgesia. After an initial test dose, the analgesia can be topped up periodically as required or an infusion pump can be commenced. Contraindications to epidurals include:

• Coagulopathy: this may cause haemorrhage into the epidural space. This may be a particular problem in pre-eclampsia

• Recent antepartum haemorrhage: epidural analgesia may be associated with a profound hypotensive episode, especially in the presence of haemorrhage

Complications of epidurals include the following:

• Dural tap is the inadvertent puncture of the dura and occurs in less than 1% of cases, but will cause a severe postural headache. It can be eased by application of a blood patch where a small sample of autologous blood is injected into the epidural space, which clots and forms a patch to prevent further leakage of cerebrospinal fluid.

• Hypotensive episodes can cause maternal and fetal distress. If this occurs, an infusion of 1 l Hartmann’s or saline over 20 minutes will generally correct the hypotension.

• Total spinal block can occur if the local anaesthetic is injected into the intrathecal space. It results in marked hypotension, bradycardia and respiratory distress that may lead to apnoea. It must be quickly recognized and the patient may need to be ventilated.

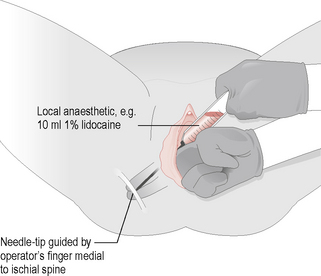

Lidocaine (nerve block) can be injected locally for perineal infiltration prior to episiotomy or instrumental delivery. Alternatively, lidocaine can be used for pudendal block by injecting it at the site where the pudendal nerve passes around the ischial spine (Fig. 14.13).

Summary

• Primiparous and multiparous labours are very different clinical entities.

• Partograms are important in the assessment of the progress of labour.

• Every labour has a different level of risk and the extent of fetal monitoring should be tailored around this, although many units rely on continuous monitoring for all patients.

• Current methods of intrapartum fetal monitoring are still unreliable and should be used in conjunction with fetal blood sampling.

• The decision to induce labour must be carefully weighted against the risk to both mother and fetus of prolonging the pregnancy.

• Induced labour has a higher incidence of operative delivery compared with spontaneous labours.

• Instrumental deliveries should only be performed for appropriate reasons, using the appropriate instrument and by a skilled practitioner.

• Preterm labour is a major cause of perinatal mortality and morbidity.