L

Labetalol hydrochloride. Combined β- and α-adrenergic receptor antagonist, with ratio of activities usually quoted between 2 : 1 and 5 : 1 respectively. Selective for α1-receptors, but non-selective at β-receptors, with some intrinsic sympathomimetic activity. Used to treat severe hypertension and pre-eclampsia, and in hypotensive anaesthesia. 90% protein-bound. Half-life is 4 h. Metabolised in the liver and excreted in urine and faeces. Undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism when given orally.

Labour, active management of. Term referring to a collection of medical interventions and management, including strict diagnostic criteria for the onset and course of labour, artificial rupture of membranes, early use of oxytocic drugs and continuous obstetric input so that the duration of labour is limited. Despite claims of improved outcome, evidence is at best conflicting.

Cephalopelvic disproportion may cause delay at any stage, but especially secondary arrest. Most other causes are treated successfully with oxytocic drugs (with continuous fetal monitoring).

Lack breathing system, see Coaxial anaesthetic breathing systems

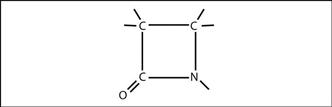

β-Lactams. Group of substances containing the 4-atom β-lactam ring (Fig. 96). Include the penicillins, cephalosporins, the monobactam aztreonam and the carbapenems. The β-lactam ring is a site of breakdown by bacterial β-lactamase, leading to bacterial resistance.

Fig. 96 Structure of β-lactam ring

Lactate. Byproduct of anaerobic metabolism of the products of glycolysis. Hypoxia prevents aerobic metabolism of pyruvate to CO2 and water (via the tricarboxylic acid cycle); instead lactate is formed, with consequent increases in plasma lactate/pyruvate ratio (normally 10) and plasma lactate (normally 0.3–1.3 mmol/l). The liver removes 70% of lactate and the rest is converted to pyruvate by mitochondria-rich skeletal and cardiac muscle.

Lactic acidosis. Metabolic acidosis accompanied by raised plasma lactate levels.

those with overt tissue hypoxia and anaerobic respiration (type A):

those with overt tissue hypoxia and anaerobic respiration (type A):

– severe hypoxaemia.

– shock/haemorrhage/hypotension.

those without apparent initial tissue hypoxia (type B), further subdivided into:

those without apparent initial tissue hypoxia (type B), further subdivided into:

– hepatic failure/renal failure (delayed clearance of lactate).

– severe infection, thiamine deficiency, alcoholic and diabetic ketoacidosis (pyruvate dehydrogenase dysfunction).

– cyanide poisoning, biguanides, salicylates, sodium valproate (uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation).

– exercise, severe infection, seizures, β-adrenergic receptor agonists, fructose and sorbitol in TPN, malignancies (increased glycolysis such that the aerobic pathway is overwhelmed).

directed at the underlying cause (with supportive therapy).

directed at the underlying cause (with supportive therapy).

minimisation of drugs that may exacerbate the problem (e.g. adrenaline).

minimisation of drugs that may exacerbate the problem (e.g. adrenaline).

cautious use of bicarbonate (increased lactate levels have followed its use).

cautious use of bicarbonate (increased lactate levels have followed its use).

Laevobupivacaine, see Bupivacaine

Lambert–Beer law, see Beer–Lambert law

Lamotrigine. Anticonvulsant drug, blocks voltage-gated sodium channels and thus inhibits the presynaptic release of glutamate and other excitatory neurotransmitters. Used for partial or secondary generalised seizures, either alone or in combination with other anticonvulsants. Has also been used for the treatment of bipolar disorders and in chronic pain management. Rapidly absorbed after oral administration with peak plasma concentrations at 2.5 h; half-life is 24–36 h. Plasma concentration is increased by sodium valproate but decreased by drugs causing enzyme induction (e.g. other anticonvulsants). It also induces its own metabolism.

Lanreotide. Long-acting somatostatin analogue; actions and effects are similar to those of octreotide. Used mainly in long-term management of acromegaly, by deep sc or im injection.

Lansoprazole. Proton pump inhibitor; actions and effects are similar to those of omeprazole.

LAP, see Left atrial pressure

– subcutaneous/mediastinal emphysema and pneumothorax.

– bradycardia or asystole due to vagal stimulation.

– gas may splint the diaphragm and reduce lung expansion.

– raised intra-abdominal pressure may increase risk of regurgitation and aspiration of gastric contents. High incidence of PONV.

– ICP is increased.

– explosion through ignition of intestinal methane by diathermy has been reported.

– reduced FRC and diaphragmatic splinting, with risk of atelectasis, hypoxaemia and hypoventilation.

– increased risk of regurgitation.

– bleeding may go unnoticed if not in the immediate area being worked on.

– large amounts of irrigating fluid may be used, with the risk of hypothermia if not warmed.

Other considerations include patient co-morbidity; e.g. obesity in patients for gastric banding. The above complications lead many anaesthetists to choose tracheal intubation and IPPV as the technique of choice, although the LMA is also commonly used for short gynaecological procedures in suitable patients.

Gerges FJ, Kanazi GE, Jabbour-Khoury SI (2006). J Clin Anesth; 18: 67–78

Laplace’s law. For a hollow distensible structure:

where P = transmural pressure

R1 = radius of curvature in one direction

R2 = radius of curvature in the other direction

For a cylinder, one radius = infinity, therefore

For a sphere, both radii are equal, therefore

• Physiological/clinical importance:

– arteriolar smooth muscle response to fluctuating intraluminal pressure: wall tension varies in order to maintain constant radius and blood flow (one theory of the mechanism of autoregulation).

– as intraluminal pressure in arterioles or airways falls, or external pressure rises, there is a critical closing pressure across the wall at which collapse may occur. In the lungs, this may occur during forced expiration, limiting expiratory air flow.

– ventricular cardiac muscle must generate greater tension when the heart is dilated than when of normal size, in order to produce the same intraventricular pressure. Thus an enlarged failing heart must contract more forcibly to sustain BP, hence the benefit of reducing preload.

– in the lungs, alveoli would tend to collapse as they became smaller, were it not for surfactant, which reduces surface tension.

– if the outlet of an anaesthetic breathing system is obstructed, the reservoir bag distends, thus limiting the dangerous build-up of pressure that would occur within a non-distensible bag.

Larrey, Baron Dominique Jean (1766–1842). French surgeon-in-chief to Napoleon. Employed refrigeration anaesthesia in 1807, and again in 1812 during the Russian campaign to allow painless amputations in half-frozen soldiers. Also employed triage. Supported Hickman when the latter presented his experiments on ‘suspended animation’ to the French Academy in 1828.

[Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), French Emperor]

Baker D, Cazalaà J-B, Carli P (2005). Resuscitation; 66: 259–62

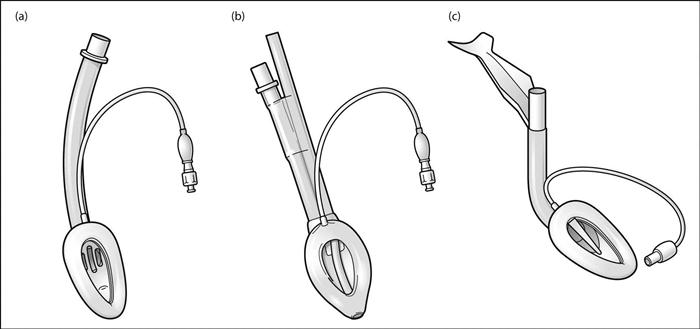

Laryngeal mask airway (LMA). Device invented by Brain and introduced into practice in 1988 for supporting and maintaining the airway without tracheal intubation. Consists of an oval head attached to a connecting tube (Fig. 97a). The head is inserted blindly into the pharynx to lie against the back of the larynx, and the circumferential cuff inflated to form a seal. Pressing the junction of the head and tube backward and upward against the palate during insertion has been recommended by the inventor; alternative methods include insertion with the bowl facing upwards and rotating it 180° once inserted. Tolerated at lighter levels of anaesthesia than a tracheal tube. Insertion is easier following propofol induction of anaesthesia than thiopental induction, because of the former’s greater suppression of laryngeal reflexes.

Has been used for spontaneous or controlled ventilation, the latter using inflation pressures of up to 10–25 cmH2O. Does not protect against aspiration of gastric contents. May be removed before the patient wakes, or left in position. A bite block is required to prevent obstruction or damage by the teeth.

routine inhalational anaesthesia.

routine inhalational anaesthesia.

airway maintenance in difficult intubation, in both previously unsuspected and known cases.

airway maintenance in difficult intubation, in both previously unsuspected and known cases.

emergency management of failed intubation.

emergency management of failed intubation.

CPR.

CPR.

Also available with reinforced tubes to prevent kinking. More recent developments include: the ProSeal LMA, which features a larger cuff (providing a better seal against the glottis), and a gastric drainage port that opens at the tip of the cuff (Fig. 97b); and the intubating LMA, in which the tube is shorter and rigid with a sharp angle. In the latter, the bars covering the laryngeal aperture are replaced by a single flap that lifts the epiglottis when a tracheal tube (a soft silicone one specifically provided for the purpose) is passed blindly through it (Fig. 97c). The intubating and standard LMAs have been used (with or without a fibreoptic ’scope) in known and unsuspected cases of difficult intubation. A version of the intubating LMA has also been introduced that incorporates a small display screen mounted at the proximal end of the airway so that intubation can be observed in real time.

Laryngeal nerve blocks, see Intubation, awake

Laryngeal nerves. Derived from the vagus nerves:

– arises at the base of the skull and passes deep to the carotid arteries.

– the internal laryngeal nerve pierces the thyrohyoid membrane with the superior laryngeal vessels, supplying the mucous membrane of the larynx down to the vocal cords.

– on the left, arises anterior to the ligamentum arteriosus, passes below and behind it and the aorta and ascends in the neck (see Fig. 113; Neck, cross-sectional anatomy).

– in the neck, ascends in the groove between the oesophagus posteriorly and trachea anteriorly.

superior laryngeal: slack cord and weak voice.

superior laryngeal: slack cord and weak voice.

if one side only is affected, the contralateral cord may move across and restore the voice.

if one side only is affected, the contralateral cord may move across and restore the voice.

Branches may be damaged during surgery (e.g. thyroidectomy) and tracheal intubation, especially if undue force is used or the cuff is inflated within the larynx. The recurrent laryngeal nerve may be involved by lesions in the neck, thorax or mediastinum (on the left).

The superior laryngeal nerve may be blocked to allow awake tracheal intubation.

[Sir Felix Semon (1849–1921), German-born English laryngologist]

Laryngeal reflex. Laryngospasm in response to stimulation of the laryngeal/hypopharyngeal mucosa. Afferent pathway is via the laryngeal nerves, vagus and brainstem.

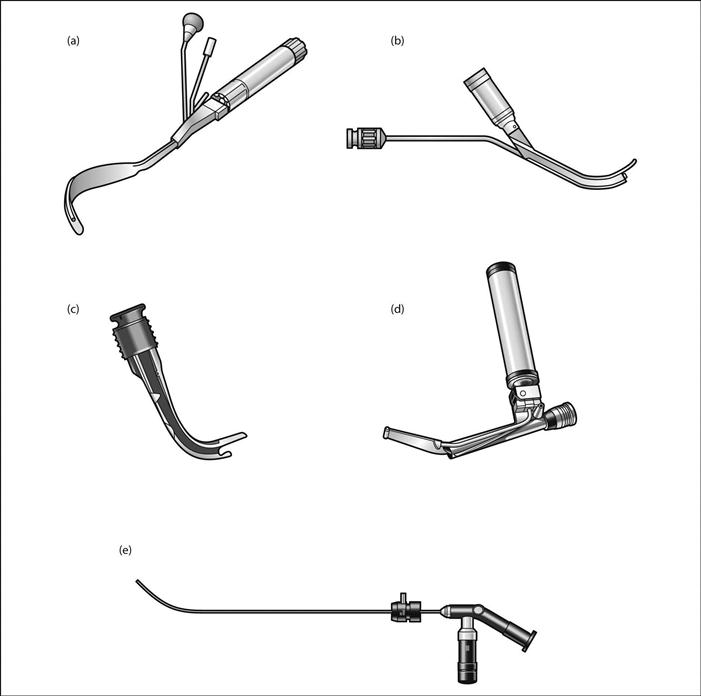

Laryngoscope. Instrument used to perform laryngoscopy. The first direct-vision laryngoscope was invented by Kirstein and later developed by Jackson; the principle was later modified by Magill, Macintosh and others.

– contains a battery power source (originally connected to mains electricity).

– short or adjustable handles are available; smaller lighter handles are usually used for paediatric anaesthesia. The Anderson laryngoscope handle bears a hook for the left index finger, allowing laryngoscopy using only the thumb and index finger whilst the other fingers of the left hand are free to apply pressure over the front of the infant’s larynx.

– usually set at right angles to the handle.

– many different laryngoscope blades have been described, most of them interchangeable when standard attachments are used.

Devices incorporating viewing channels or with video chips at the distal end allow either placement of the device in the trachea under visual control, with advancement of the tracheal tube over it, or identification of the glottis and observation of the tube’s passage through the vocal cords. The image may be viewed by looking through an eyepiece, attachment to a camera/video system or via a screen incorporated into the device itself (Fig. 98). Flexible fibreoptic instruments are also available.

Concerns over cross-infection, especially transmission of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, have led to widespread use of disposable laryngoscope blades, laryngoscopes or blade covers/sheaths.

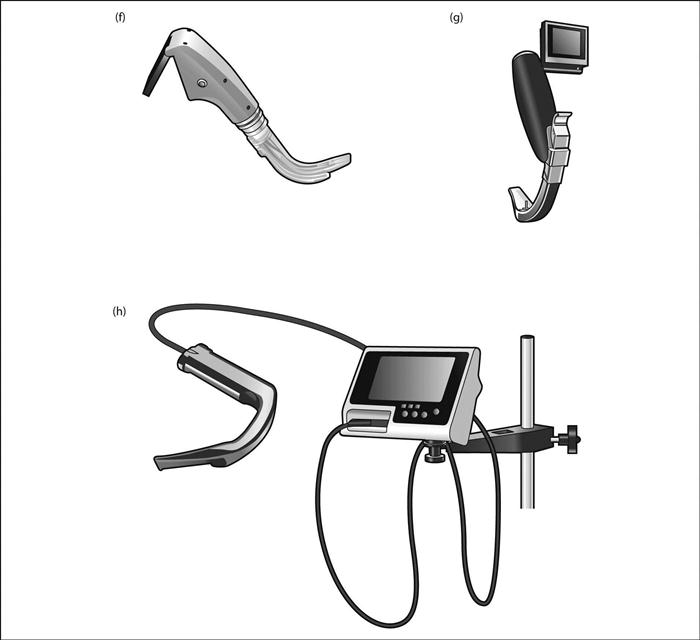

Laryngoscope blades. Parts of laryngoscopes inserted into the mouth.

base for attachment to handle.

base for attachment to handle.

flange: parallel to the tongue; usually only present for the proximal one- to two-thirds of the blade.

flange: parallel to the tongue; usually only present for the proximal one- to two-thirds of the blade.

Most are designed for use with the laryngoscope handle held in the left hand; i.e. the tongue is pushed to the left side of the patient’s mouth by the flange and web.

• Common varieties (Fig. 99a):

Macintosh (1943): tongue, web and flange form a reverse Z shape in cross-section. The most commonly used blade in the UK; also popular in the USA. Available in large adult, adult, child and baby sizes; the latter size was not designed by Macintosh and was criticised by him as being anatomically incorrect. A ‘left-handed’ version is available, for use when anatomical features of the airway require insertion of the tracheal tube from the left side of the mouth instead of the right. The McCoy blade (1993) is hinged at the tip, and is controlled by a lever on the laryngoscope handle. It allows elevation of the epiglottis whilst reducing the amount of force required during laryngoscopy. Although it may make a difficult laryngoscopy easier, it may also make an easy one more difficult. Another blade with a similar function to the McCoy is actually flexible throughout its length; its curvature is increased by a lever on the handle.

Macintosh (1943): tongue, web and flange form a reverse Z shape in cross-section. The most commonly used blade in the UK; also popular in the USA. Available in large adult, adult, child and baby sizes; the latter size was not designed by Macintosh and was criticised by him as being anatomically incorrect. A ‘left-handed’ version is available, for use when anatomical features of the airway require insertion of the tracheal tube from the left side of the mouth instead of the right. The McCoy blade (1993) is hinged at the tip, and is controlled by a lever on the laryngoscope handle. It allows elevation of the epiglottis whilst reducing the amount of force required during laryngoscopy. Although it may make a difficult laryngoscopy easier, it may also make an easy one more difficult. Another blade with a similar function to the McCoy is actually flexible throughout its length; its curvature is increased by a lever on the handle.

Magill (1926): U-shaped in cross-section.

Magill (1926): U-shaped in cross-section.

• Specific paediatric blades (Fig. 99b):

• Others:

Guedel and Flagg (1928): similar to Magill’s, but with the bulb at the tip. Guedel’s is set at an acute angle to the handle.

Guedel and Flagg (1928): similar to Magill’s, but with the bulb at the tip. Guedel’s is set at an acute angle to the handle.

Siker (1956): angled blade incorporating a mirror at the angle.

Siker (1956): angled blade incorporating a mirror at the angle.

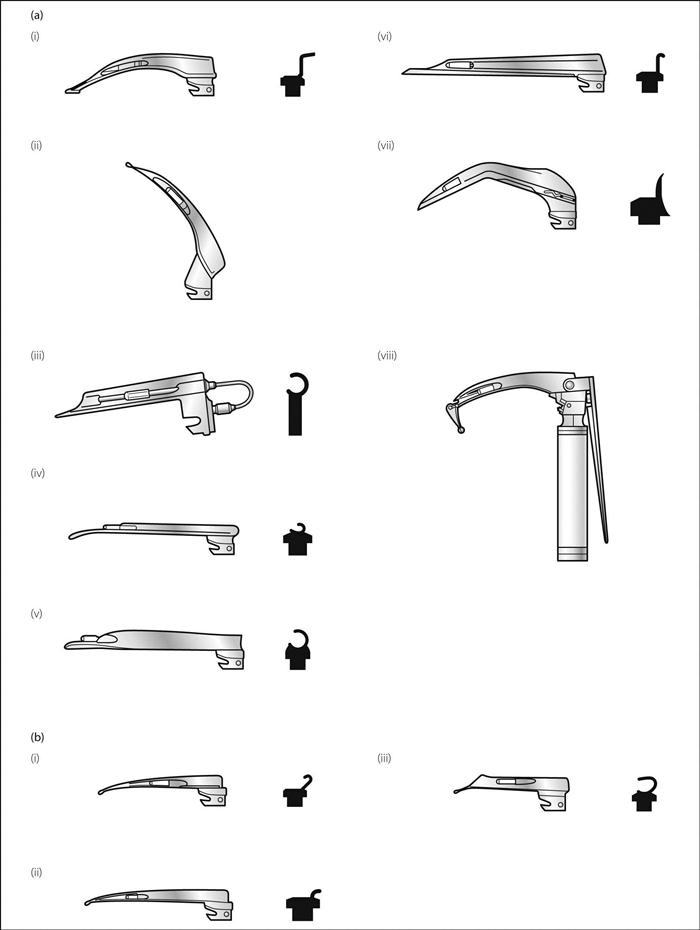

Laryngoscopy. Act of viewing the larynx. Indirect laryngoscopy was first described in 1855 in London by Garcia using a mirror. Direct laryngoscopy was pioneered by Kirstein, Killian and Jackson in the late 1800s/early 1900s, and is now the technique most commonly used for tracheal intubation. The view of the larynx during direct laryngoscopy is shown in Fig. 100.

Anaesthesia for diagnostic or therapeutic laryngoscopy must provide relaxation of the jaw and vocal cords, with rapid recovery of laryngeal reflexes without laryngospasm. Problems include sharing of the airway, the hypertensive response to laryngoscopy and contamination of the airway with blood and debris. Usually performed under general anaesthesia, with IPPV through a special 5–6 mm ‘microlaryngoscopy’ cuffed tracheal tube (resistance is too high for spontaneous ventilation). Other methods include injector and insufflation techniques as for bronchoscopy. Spraying the cords with lidocaine reduces postoperative laryngospasm but at the expense of diminished laryngeal reflexes.

[Manuel Garcia (1805–1906), Spanish singing teacher]

See also, Intubation, complications of; Intubation, difficult; Intubation, tracheal

Laryngospasm. Reflex closure of the glottis by adduction of the true and/or false cords. May persist after cessation of its stimulus. The precise mechanism is controversial; the lateral cricoarytenoid muscles are thought to be most important in adducting the cords whilst cricothyroid tenses them. The extrinsic muscles of the larynx may also have a role.

response to other stimulation, e.g. surgery, movement, stimulation of anus, cervix (Brewer–Luckhardt reflex).

response to other stimulation, e.g. surgery, movement, stimulation of anus, cervix (Brewer–Luckhardt reflex).

May cause complete or partial airway obstruction, the latter often presenting as inspiratory stridor. Causes hypoxaemia and hypoventilation; pulmonary oedema has been reported.

when laryngospasm has subsided, depth of anaesthesia may be deepened.

when laryngospasm has subsided, depth of anaesthesia may be deepened.

laryngeal muscle relaxation may be achieved with suxamethonium (as little as 8–10 mg may suffice) or propofol, followed by ventilation with O2 and tracheal intubation if necessary.

laryngeal muscle relaxation may be achieved with suxamethonium (as little as 8–10 mg may suffice) or propofol, followed by ventilation with O2 and tracheal intubation if necessary.

local anaesthetic spray to the larynx and laryngeal nerve blocks.

local anaesthetic spray to the larynx and laryngeal nerve blocks.

use of neuromuscular blocking drugs and tracheal intubation.

use of neuromuscular blocking drugs and tracheal intubation.

protects the tracheobronchial tree and lungs, e.g. during swallowing.

protects the tracheobronchial tree and lungs, e.g. during swallowing.

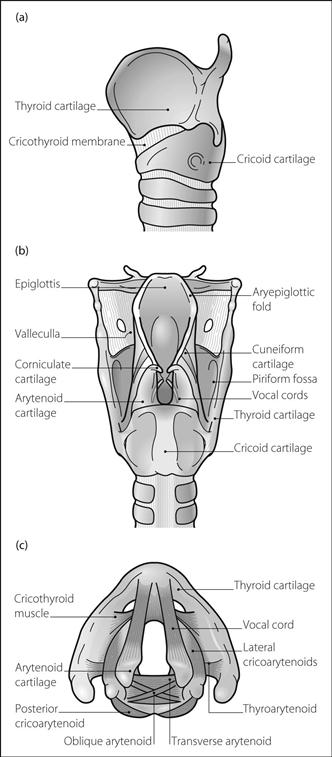

Extends from the root of the tongue to the cricoid cartilage, i.e. level with C3–6 (at higher level in children).

length: 45 mm (men); 35 mm (women).

length: 45 mm (men); 35 mm (women).

anteroposterior: 35 mm (men); 25 mm (women).

anteroposterior: 35 mm (men); 25 mm (women).

transverse: 45 mm (men); 40 mm (women).

transverse: 45 mm (men); 40 mm (women).

• Composed of hyoid bone, and epiglottic, thyroid, cricoid, arytenoid, corniculate and cuneiform cartilages, joined by several muscles and ligaments (Fig. 101):

– attached posteriorly to the pharynx by the middle constrictor muscle.

– attached to the arytenoid laterally by the aryepiglottic membrane.

– attached superiorly to the hyoid bone by the thyrohyoid membrane and muscle.

– attached via its superior surface to the thyroid cartilage by the cricothyroid membrane.

– attached via its posterior surface to the arytenoids by the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles.

– attached inferiorly to the trachea by the cricotracheal membrane.

– pyramid-shaped, the bases articulating with the back of the cricoid.

– also attached to the cricoid by posterior and lateral cricoarytenoid muscles.

– the vocal cords pass from the vocal processes anteriorly to the back of the thyroid cartilage.

– attached to the epiglottis superomedially via the aryepiglottic folds and muscles.

– attached anterolaterally to the back of the thyroid cartilages by the thyroarytenoid muscles.

– attached to each other by the transverse arytenoid muscle.

cuneiform cartilages: lie anterior to the corniculate cartilages, in the aryepiglottic folds.

cuneiform cartilages: lie anterior to the corniculate cartilages, in the aryepiglottic folds.

• Membranes and areas of the larynx:

– passes from the anterior arytenoid to lateral epiglottis.

thyrohyoid membrane: lateral borders are thickened to form the lateral thyrohyoid ligaments.

thyrohyoid membrane: lateral borders are thickened to form the lateral thyrohyoid ligaments.

The entrance to the larynx slopes downwards and backwards, bounded anteriorly by the epiglottis, laterally by the aryepiglottic folds and posteriorly by the arytenoid cartilages. The piriform fossa is the recess on each side, between the aryepiglottic folds medially and thyroid cartilage and thyrohyoid membrane laterally. The rima glottidis is the narrowest part of the airway in adults; the cricoid is the narrowest in children.

• Epithelium: squamous above the cords, columnar below. Mucosa of the cords is closely adherent.

the cords are tensed by cricothyroid and relaxed by thyroarytenoid and vocalis muscles.

the cords are tensed by cricothyroid and relaxed by thyroarytenoid and vocalis muscles.

the inlet is opened by the thyroepiglottic muscle and closed by the aryepiglottic muscle.

the inlet is opened by the thyroepiglottic muscle and closed by the aryepiglottic muscle.

recurrent laryngeal nerve: all muscles except cricothyroid, and sensation below vocal cords.

recurrent laryngeal nerve: all muscles except cricothyroid, and sensation below vocal cords.

superior laryngeal nerve: cricothyroid muscle, and sensation above vocal cords.

superior laryngeal nerve: cricothyroid muscle, and sensation above vocal cords.

• Blood supply: branches of superior and inferior thyroid arteries and accompanying veins.

• Effects of the laser beam on tissues depend on its wavelength:

CO2 laser (wavelength 10 600 nm): used for precise surgical cutting and coagulation, e.g. in ENT surgery, neurosurgery, general and gynaecological surgery and dermatology.

CO2 laser (wavelength 10 600 nm): used for precise surgical cutting and coagulation, e.g. in ENT surgery, neurosurgery, general and gynaecological surgery and dermatology.

argon or krypton (400–700 nm): used for photocoagulation in ophthalmology and dermatology.

argon or krypton (400–700 nm): used for photocoagulation in ophthalmology and dermatology.

• Risks to patient and operating staff:

skin damage: prevented by appropriate draping of the patient.

skin damage: prevented by appropriate draping of the patient.

explosions and fires: particularly problematic during upper airway surgery, when the high-energy beams may cause ignition of anaesthetic vapours, rubber, PVC or silicone tracheal tubes or drapes. The following precautions are available:

explosions and fires: particularly problematic during upper airway surgery, when the high-energy beams may cause ignition of anaesthetic vapours, rubber, PVC or silicone tracheal tubes or drapes. The following precautions are available:

– flexible metal tracheal tubes without cuffs.

– avoidance of tracheal intubation, e.g. use of insufflation or injector techniques, including high-frequency ventilation.

– limitation of laser power and duration of bursts.

gas embolism if the probe’s tip is gas-cooled.

gas embolism if the probe’s tip is gas-cooled.

production of noxious/potentially infective fumes: adequate suction is required.

production of noxious/potentially infective fumes: adequate suction is required.

Latent heat. Energy released or absorbed when a substance undergoes a change of state, without a change in its temperature, e.g.:

Specific latent heat is the energy required to alter the state of unit mass of substance at specified temperature; e.g. specific latent heat of vaporisation of water = 2.26 MJ/kg at 100°C. It is greater at lower temperatures, and falls at higher temperatures until it reaches zero at the critical temperature.

Lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm, block, see Elbow, nerve blocks

Lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, block. Provides analgesia of the lateral thigh (e.g. for hip surgery), following skin harvesting, and to reduce leg tourniquet pain. Has also been used in pain states and to diagnose entrapment neuropathy of the nerve caused by the latter’s piercing the inguinal ligament instead of passing under it (meralgia paraesthetica), before surgical treatment.

The nerve (L2–3) arises from the lumbar plexus (may arise from the femoral nerve), passing under the inguinal ligament just medial to the anterior superior iliac spine to supply the skin of the lateral side of the thigh (see Fig. 67; Femoral triangle). A needle is inserted 2 cm medial and inferior to the iliac spine, at right angles to the skin. A click is felt as the fascia lata is pierced. 10–15 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected fanwise, mediolaterally.

May also be blocked via femoral nerve block (three-in-one block).

Latex allergy. Typically occurs in individuals repeatedly exposed to latex, e.g. healthcare workers and patients undergoing repeated urinary catheterisation (e.g. those with spina bifida) or surgery. Thought to be true anaphylaxis to various soluble proteins in latex.

Evaluation includes skin-testing, in vitro leucocyte studies and testing for anti-latex IgE antibodies. Perioperative management includes avoidance of all latex-containing equipment including facemasks, gloves, airways/tubes, rebreathing bags/bellows, bungs, drains and catheters. Drug vials with rubber tops and iv tubing with rubber injection ports should be avoided. Protection of the arm with gauze before application of a rubber BP cuff has been suggested, although cuffs and other equipment are increasingly manufactured without latex. Pretreatment with antihistamine drugs, H2 antagonist drugs and corticosteroids has been used but may not be necessary if proper precautions have been taken. Since airborne latex particles have triggered allergic reactions, no latex-containing equipment should be used in the operating room before a known case; scheduling surgery for the beginning of the operating list has been advocated. A high index of suspicion and availability of resuscitative drugs are important; management of a reaction should follow standard lines as for adverse drug reactions.

Laudanosine. Tertiary amine, a product of atracurium metabolism via Hofmann degradation. Half-life is about 2–3 h, i.e. considerably longer than for atracurium; approximately doubled in renal failure. In anaesthetised dogs, causes epileptiform EEG changes at blood levels over 17 µg/ml. Blood levels in humans, even after several days’ infusion of atracurium in patients with renal and hepatic failure, rarely rise above 5 µg/ml, although fears have been expressed about central stimulation in patients at risk, e.g. those with an impaired blood–brain barrier. Cisatracurium at equipotent doses produces one-fifth of the level of laudanosine. Has recently been found to have analgesic effects in animals, and to interact with central GABA, opioid and acetylcholine receptors.

Fodale V, Santamaria LB (2002). Eur J Anaesthesiol; 19: 466–73

Lavoisier, Antoine Laurent (1742–1794). French chemist. Disproved the phlogiston theory, showing that the gain in weight of sulphur or phosphorus on combustion was due to combination with air. Concluded that air consists of two elastic fluids: one necessary for combustion and respiration, and one that would support neither. Renamed the former (previously called dephlogisticated air) oxygène, estimating its concentration in air to be about 25%.

Lawen, Arthur (1876–1958). German surgeon, the first to perform caudal analgesia for abdominal surgery, using large volumes of procaine. Also described paravertebral block, and helped popularise regional anaesthesia. Described the use of curare to produce relaxation during surgery in 1912.

to prepare the lower GIT before surgery.

to prepare the lower GIT before surgery.

to reduce pain following rectal or anal surgery.

to reduce pain following rectal or anal surgery.

to treat constipation, e.g. on ICU or postoperatively.

to treat constipation, e.g. on ICU or postoperatively.

to treat poisoning and overdoses, e.g. whole bowel irrigation, especially in children.

to treat poisoning and overdoses, e.g. whole bowel irrigation, especially in children.

osmotic laxatives: cause retention of water within the bowel. Include lactulose (broken down by gut bacteria to osmotically active compounds; also reduce ammonia production, hence its use in hepatic failure), polyethylene glycols and rectal citrate or phosphates (caution in renal impairment since hyperphosphataemia may result). Magnesium salts act within 2–4 h but should not be used in renal impairment because of systemic absorption.

osmotic laxatives: cause retention of water within the bowel. Include lactulose (broken down by gut bacteria to osmotically active compounds; also reduce ammonia production, hence its use in hepatic failure), polyethylene glycols and rectal citrate or phosphates (caution in renal impairment since hyperphosphataemia may result). Magnesium salts act within 2–4 h but should not be used in renal impairment because of systemic absorption.

bowel cleansers: usually mixtures of agents; should not be used in constipation. In frail patients, preoperative use may result in significant dehydration. Used in whole bowel irrigation.

bowel cleansers: usually mixtures of agents; should not be used in constipation. In frail patients, preoperative use may result in significant dehydration. Used in whole bowel irrigation.

Dosage depends on the particular preparation used. Complications include dehydration and electrolyte disturbances. Stimulants may cause abdominal cramps; osmotic laxatives may cause bloating. Laxatives (especially stimulants) are contraindicated in intestinal obstruction.

Le Fort classification, see Facial trauma

Left atrial pressure (LAP). Mean pressure approximates to left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, unless the mitral valve is abnormal. Pressure wave abnormalities are similar to the venous waveform, but with reference to mitral and aortic valves and systemic circulation, instead of tricuspid and pulmonary valves and pulmonary circulation.

May be measured via a catheter inserted directly into the left atrium, or indirectly via pulmonary artery catheterisation, which measures pulmonary capillary wedge pressure. Usually measured from mid-axilla or sternal angle. Normal value is 2–10 mmHg.

Left ventricular ejection time, see Systolic time intervals

Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP). Reflects the preload of the left ventricle. Provided ventricular compliance is constant, a constant relationship (exponential rather than linear) exists between LVEDP and left ventricular end-diastolic volume. Normal LVEDP does not ensure normal ventricular function, and abnormal LVEDP may not indicate degree of dysfunction. Elevations of LVEDP (normally under 12 mmHg) may reflect increased blood volume, reduced myocardial contractility, reduced ventricular compliance and increased venous return. May be measured directly via a ventricular cannula or arterial cannulation, or inferred via pulmonary artery catheterisation.

Left ventricular end-diastolic volume. Nearest physiological variable to left ventricular preload, as described by Starling’s law. May be assessed using echocardiography or radiology, but indicators of left ventricular end-diastolic pressure are easier to measure. Normally 70–95 ml/m2.

Left ventricular failure, see Cardiac failure

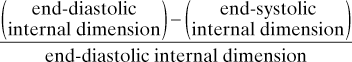

Left ventricular fractional shortening. Indicator of left ventricular function derived from M-mode echocardiography.

Normally 34–44%; often easier to estimate during echocardiography than doing a formal evaluation of ejection fraction.

Left ventricular stroke work, see Stroke work

Legionnaires’ disease. Caused by Legionella pneumophila, Gram-negative aerobic bacteria. First came to prominence when it killed 29 delegates at an American Legion convention in 1976. More likely to affect elderly patients. Acquired by inhaling contaminated water particles, especially derived from cooling towers; typically occurs in epidemics involving a single building. Presents as an acute febrile chest infection, typically with myalgia, fatigue and GIT upset before respiratory symptoms develop. Pleuritic chest pain and confusion may occur. Widespread infiltrates may be present on CXR. Diagnosis is via sputum culture ± serological testing. Treatment is with erythromycin or clarithromycin; 4-quinolones have also been used. The disease lasts for 7–10 days. Mortality rates of 10–30% have been reported.

Lenograstim, see Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

Lepirudin. Recombinant hirudin, used as an alternative to heparin if the latter induces immune thrombocytopenia.

Leptospirosis (Weil’s disease). Caused by species of leptospira, Gram-negative aerobic bacteria. Passed from asymptomatic animals (dogs, rodents, livestock and wild animals) via their urine to water, where it may survive for many months. Typically affects sewage workers. Acquired via mucous membranes and broken skin; it causes widespread vasculitis affecting the kidney, liver, lungs and heart. Clinical features include fever, myalgia, headache/neck stiffness, cough, chest pain, confusion, rash and occasionally renal and hepatic failure. Diagnosed retrospectively by increases in antibody titre. Treatment is with benzylpenicillin, erythromycin or tetracyclines. Normal organ function returns usually within 1–2 months. Mortality is up to 11% if hepatic failure occurs.

Letheon. Name given to diethyl ether by Morton in 1846 when he patented his discovery. Despite this patent, ether was widely used without acknowledgement of Morton’s claim. His attempts to enforce the patent and payments of royalties included approaching the governments of the USA and France, but were unsuccessful.

[Lethe (Greek mythology), river in Hades whose waters induced forgetfulness in those who drank them]

Leucocytes. White blood cells; normal total count in peripheral blood is 4–10 × 109/l.

• Exist as three morphologically different types:

granulocytes: derived from common bone marrow precursor stem cells:

granulocytes: derived from common bone marrow precursor stem cells:

– neutrophils (60–70%; 2.5–7 × 109/l): phagocytic with high enzyme content.

– eosinophils (1–4%; 0.01–0.4 × 109/l): contain histamine and are involved in cell-mediated hypersensitivity reactions.

– basophils (0–1%; 0–0.2 × 109/l): contain histamine and heparin; non-phagocytic.

lymphocytes (23–35%: 1–3.5 × 109/l): derived from lymphoid stem cells throughout the body, including bone marrow. Mainly concerned with immune mechanisms: B (bursa) cells with immunoglobulin production and T (thymus) cells with immune system regulation and killing of infected cells.

lymphocytes (23–35%: 1–3.5 × 109/l): derived from lymphoid stem cells throughout the body, including bone marrow. Mainly concerned with immune mechanisms: B (bursa) cells with immunoglobulin production and T (thymus) cells with immune system regulation and killing of infected cells.

Leucocytosis may be caused by almost any acute illness as part of the inflammatory response. Other causes include strenuous exercise, trauma, surgery, burns, and glucocorticoid therapy. Leucopenia may be caused by reduced production (e.g. drugs, radiation, inflammation, infection, infiltration of bone marrow by malignancy, fibrosis) or increased utilisation (e.g. sequestration into the tissues). Thus, in severe illness, white cell count may be increased or decreased. A low count appears to be prognostic of increased mortality in ICU patients.

Leukotriene pathway inhibitors. Group of drugs that block the synthesis of all leukotrienes; have been used in asthma along with the leukotriene receptor antagonists. Zileuton is an example, and inhibits the action of 5-lipoxygenase.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists. Group of drugs that block the action of cysteinyl leukotrienes at their receptors, especially on bronchial smooth muscle. Have been used orally in mild/moderate asthma but not indicated for treatment of acute attacks. Churg–Strauss syndrome (eosinophilia, systemic vasculitis and worsening pulmonary symptoms) has been reported following their use. Examples include montelukast, zafirlukast and pranlukast.

[Jacob Churg (1910–2005; Polish-born) and Lotte Strauss (1913–1985; German-born), US pathologists]

Leukotrienes. Inflammatory mediators derived from arachidonic acid by the action of lipoxygenases. Released from mast cells, platelets and some leucocytes following various stimuli (e.g. mechanical, thermal, infective and immunological). Actions include bronchoconstriction, vasoconstriction, increased vascular permeability and chemotaxis of other inflammatory cells.

They have been implicated in the pathophysiology of sepsis, acute lung injury and asthma. Leukotriene pathway inhibitors and leukotriene receptor antagonists have been developed for use in asthma.

Peters-Golden M, Henderson WR (2007). N Engl J Med; 357: 1841–54

Levallorphan tartrate. Opioid receptor antagonist with partial agonist properties, the n-allyl derivative of levorphanol. Synthesised in 1950. 1.25 mg levallorphan has been combined with 100 mg pethidine as pethilorphan, but hopes of analgesia without respiratory depression were not realised. Its use has been superseded by naloxone.

Levetiracetam. Anticonvulsant drug used as monotherapy or as an adjunct in the treatment of partial or generalised epilepsy and for myoclonic seizures. Mechanism of action is unknown.

Levofloxacin. Antibacterial drug, one of the 4-quinolones related to ciprofloxacin but more active against pneumococci.

Levorphanol tartrate. Synthetic opioid analgesic drug, synthesised in 1949. Similar to morphine but less sedating. Onset of action is under 30 min, lasting for up to 8 h. No longer available in the UK.

Levosimendan. One of the calcium sensitisers, used as an inotropic drug in the treatment of decompensated congestive cardiac failure. Shown to improve survival and cardiac function compared with placebo and dobutamine; unlike the latter, levosimendan has no pro-arrhythmic side effects.

Acts by binding to cardiac troponin C, increasing its sensitivity to calcium; thus increases myocardial contractility without increasing myocardial O2 consumption. Also causes vasodilatation by opening ATP-sensitive K+ channels in smooth muscle; hence sometimes referred to as an ‘ino-dilator’. Reductions in arterial (systemic and pulmonary) and venous tone decrease afterload (both right and left ventricular) and preload respectively.

Lidocaine hydrochloride (Lignocaine). Amide local anaesthetic agent, introduced in 1947 (revolutionising regional anaesthesia because of its superior safety to previous agents). The standard drug against which other local anaesthetics are compared. pKa is 7.9. 65% protein-bound; 95% of an injected dose undergoes hepatic metabolism and is excreted renally. Onset is rapid by all routes; usual duration of action for 1% solution is about 1 h, increased to 1.5–2 h if adrenaline is added.

• Uses:

– depression of laryngeal and tracheal reflexes (e.g. during tracheal intubation/extubation). Commonly used to reduce the increase in ICP caused by laryngoscopy. Possibly reduces muscle pains and potassium increase after suxamethonium. It has been used to produce analgesia and general anaesthesia (although its therapeutic ratio is low). 4–10% lidocaine has been used instead of air to inflate the tracheal tube cuff, thereby reducing postoperative sore throat and hoarseness.

– class I antiarrhythmic drug in ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

– may be useful in treatment of chronic pain.

• Many preparations are available, including:

0.25–0.5% solutions for infiltration anaesthesia and IVRA.

0.25–0.5% solutions for infiltration anaesthesia and IVRA.

1–2% solutions for nerve blocks and epidural anaesthesia.

1–2% solutions for nerve blocks and epidural anaesthesia.

4% solution for topical anaesthesia of the mucous membranes of the mouth, pharynx and respiratory tract.

4% solution for topical anaesthesia of the mucous membranes of the mouth, pharynx and respiratory tract.

also available in 1–2% gel for urethral instillation, and 5% ointment for skin, rectum and other mucous membranes. A constituent of EMLA cream. In other countries (especially the USA), 5% hyperbaric solution has been used in spinal anaesthesia (but see below).

also available in 1–2% gel for urethral instillation, and 5% ointment for skin, rectum and other mucous membranes. A constituent of EMLA cream. In other countries (especially the USA), 5% hyperbaric solution has been used in spinal anaesthesia (but see below).

• Dosage:

Adverse effects are as for local anaesthetic agents. Lidocaine is thought to be more toxic to nerve tissue when directly applied than other local anaesthetics, hence the increased incidence of transient radicular irritation syndrome following its use for spinal anaesthesia than with other drugs (hyperbaricity of the solution and use of very thin needles/catheters are also thought to contribute by encouraging pooling of drug around spinal nerves). This has led to revision of the drug’s data sheet to specify dilution to 2.5% before administration (even this concentration has been implicated in causing transient symptoms). Maximal recommended dose: 3 mg/kg without adrenaline, 7 mg/kg with adrenaline. Toxic plasma levels: above about 10 µg/ml.

Life support, see Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Lightwand. Device used to place a tracheal tube without requiring laryngoscopy. Consists of a flexible malleable stylet incorporating a light bulb at the distal end, with the battery and handle at the proximal end. Placed inside a tracheal tube with the bulb at the tube’s tip, the tube/lightwand combination is bent into a J shape and manoeuvred into the larynx, with successful placement indicated by a glow at the anterior neck below the thyroid prominence. The tracheal tube is then passed into the trachea and the lightwand removed. Oesophageal placement is suggested by a more diffuse glow above the prominence.

Agro F, Hung OR, Cataldo R, et al (2001). Can J Anesth; 48: 592–9

Likelihood ratio. Method of quantifying the relative probabilities of two complementary hypotheses. For a predictive test, it equals the probability that a person with the condition has a positive test, over the probability that a person without the condition has a positive test. Also equals sensitivity divided by (1 minus specificity).

Limbic system. Part of the brain, formerly termed the rhinencephalon. Composed of left and right lobes, each consisting of:

Thought to be one site of action of benzodiazepines and possibly other anaesthetic drugs.

LiMON. Commercial non-invasive monitor of liver function and blood volume. Requires peripheral or central venous access and uses a four-wavelength near infrared finger sensor. Measures the plasma disappearance rate and the 15-min retention rate of an intravenous marker, indocyanine green. Knowledge of the cardiac output permits estimation of circulating blood volume and indocyanine green clearance within minutes. As the elimination of indocyanine green is dependent on both liver blood flow and hepatocellular function, the system cannot differentiate the cause of a reduced clearance of indocyanine green. However, any sudden reduction in clearance will reflect a fall in liver blood flow. Up to 10 measurements are possible in any 24-h period.

Linear analogue scale (Visual analogue scale). Method of evaluating pain, nausea, anxiety and other symptoms, e.g. for statistical analysis. For example, for pain evaluation, a horizontal 10 cm line is drawn on plain paper, with ‘no pain’ written at the left-hand end, and ‘worst possible pain’ at the right-hand end. The patient marks his or her position on the line. Thought to be more reliable than assessments where patients choose the most appropriate number or word from a list, which may be influenced by personal preference for certain words or numbers and limited by the number of choices offered. Thought to be consistent for any individual; however, because patients may interpret the analogue scale differently, comparison between patients may be unreliable. Also, patients tend to avoid the extremes of the scale, clustering their scores around the middle; the scale is thus not truly linear.

Linezolid. Oxazolidinone antibacterial drug active against Gram-positive bacteria, including multiresistant staphylococci and enterococci, but poorly active against Gram-negative organisms.

Lingual nerve block, see Mandibular nerve blocks

Lipid emulsion. Fat emulsion for iv administration composed of soya bean oil, glycerol and egg phospholipids. Available in 10%, 20% and 30% concentration (of soya oil) for parenteral nutrition. 20% emulsion is the recommended treatment for circulatory arrest due to local anaesthetic agents (and should also be considered for severe toxicity without loss of circulation). Animal studies and case reports also support its use in the treatment of poisoning with other lipophilic drugs, including: β-adrenergic receptor antagonists; calcium channel blocking drugs; tricyclic antidepressant drugs; and neuroleptic drugs (e.g. haloperidol). Few adverse effects have been associated with its use in acute poisoning, although pancreatitis may occur with acute hyperlipidaemia.

Turner-Lawrence DE, Kerns Li W (2008). J Med Toxicol; 4: 109–14

Lipopolysaccharide, see Endotoxins

Liquid ventilation. Technique of partially or totally filling the lungs with perfluorocarbons (especially perfluorooctylbromide) and ventilating with this liquid instead of O2-enriched air. First done experimentally in animals in the early 1960s, using pressurised crystalloid solutions. Has been used in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome and ARDS, mostly in animal models, but human studies have been and are currently being performed.

In total liquid ventilation, the entire lung volume and ventilator circuit are filled, requiring a specialised ventilator. The liquid is oxygenated to a PO2 of 50–90 kPa (350–675 mmHg) by either bubbling O2 through it or by using a standard extracorporeal device. Tidal volumes of 15–20 ml/kg are given at a rate of about 5 breaths/min. In partial liquid ventilation (perfluorocarbon-associated gas exchange; PAGE) a volume approximating to FRC is instilled and standard IPPV continued. Results in improved oxygenation and increased compliance, thought to be via increased recruitment of non-aerated alveoli and redistribution of perfusion. A protective effect against further lung injury has been suggested.

Kaisers U, Kelly KP, Busch T (2003). Br J Anaesth; 91: 143–51

Lissive anaesthesia. Obsolete technique of anaesthesia in which small doses of non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drugs (originally tubocurarine) were used to produce muscle relaxation without causing complete paralysis, allowing spontaneous respiration ‘diaphragmatic sparing’.

Liston, Robert (1794–1847). Scottish-born surgeon; performed the first operation under diethyl ether anaesthesia in England on 21 December 1846, at University College Hospital, London, having been told about ether by Boott. William Squire administered the anaesthetic from a glass inhaler made by his uncle, Peter, whilst Frederick Churchill had an above-knee amputation. The operation allegedly lasted 25 s.

Lithium carbonate/citrate. Salts used for manic-depressive disease. Lithium mimics sodium in the body, entering excitable cells during depolarisation. It decreases release of central and peripheral neurotransmitters and may prolong depolarising and non-neuromuscular blockade and decrease requirements for anaesthetic agents. Termination 24 h before anaesthesia has been suggested but this is disputed. Has low therapeutic ratio, with optimal plasma concentration of 0.4–1.0 mmol/l and toxicity occurring at > 1.5 mmol/l. Distributed slowly within the tissues (24–36 h with slow-release preparations). Almost entirely excreted by the kidneys, with half-life 6–12 h initially but > 24 h if the tissue compartment contains significant amounts of drug. Lithium poisoning may occur acutely and deliberately, or insidiously during chronic treatment as a result of dehydration, impaired renal function, infection and use of drugs, e.g. NSAIDs, diuretics.

Lithium poisoning. Toxic effects of lithium may be seen at plasma concentrations of < 1.0 mmol/l but are common at > 1.5 mmol/l; severe toxicity is usual at levels > 2.0 mmol/l, although acute poisoning may produce high concentrations before the onset of symptoms. Features include lethargy or restlessness initially; then tremor, ataxia, GIT upset, weakness and muscle twitching; finally, hypokalaemia, arrhythmias, renal failure, convulsions and coma.

Management consists of increasing urine output if symptoms have not yet developed; general treatment is supportive with control of electrolyte imbalance and convulsions, and haemodialysis (that may need repeating as lithium redistributes from the tissues to the circulation) if neurological symptoms are present or if plasma concentration is > 7.5 mmol/l after acute overdose (or > 4 mmol/l in chronic overdose). The possibility of prolonged absorption of lithium from slow-release preparations should be remembered. Activated charcoal is relatively ineffective at preventing further absorption; whole bowel irrigation has been used but is not standard therapy.

Litre. SI unit of volume. Originally defined as the volume of 1 kg pure water at 4°C, but redefined as equal to 1000 cm3 in 1964, because of an error in the standard kilogram constructed in 1889.

Liver. Largest body organ, weighing about 1200–1500 g, lying in the right upper abdominal quadrant. Two major lobes, right and left, are divided into lobules based on a central vein connected by a network of sinusoids to peripheral portal tracts. Central veins are tributaries of hepatic veins; portal tracts contain branches of the hepatic artery, portal vein, lymphatics and bile ducts. Blood from the hepatic arterial and portal venous systems is conveyed to the central veins via the sinusoids, lined with endothelial and phagocytic (Kupffer) cells and separated by hepatocytes. Bile canaliculi form networks between the hepatocytes, conveying bile towards the biliary tract.

Blood flow is about 20–30% of cardiac output (70% via the portal vein).

carbohydrate metabolism: glycogen storage and breakdown.

carbohydrate metabolism: glycogen storage and breakdown.

protein metabolism: synthesises many, including albumin, globulins, coagulation factors, complement proteins, transferrin, haptoglobulins, caeruloplasmin, plasma cholinesterase and α1-antitrypsin. Important site of amino acid deamination before interconversion and oxidation. Ammonia produced by deamination is converted to urea.

protein metabolism: synthesises many, including albumin, globulins, coagulation factors, complement proteins, transferrin, haptoglobulins, caeruloplasmin, plasma cholinesterase and α1-antitrypsin. Important site of amino acid deamination before interconversion and oxidation. Ammonia produced by deamination is converted to urea.

fat metabolism: breakdown of dietary triglycerides and fatty acids, and synthesis of triglycerides, phospholipid and cholesterol, released into the bloodstream as lipoproteins. Cholesterol is also used to make bile acids.

fat metabolism: breakdown of dietary triglycerides and fatty acids, and synthesis of triglycerides, phospholipid and cholesterol, released into the bloodstream as lipoproteins. Cholesterol is also used to make bile acids.

bilirubin metabolism: unconjugated fat-soluble bilirubin is transported to the liver bound to albumin; it is conjugated with glucuronide to the water-soluble form (see Jaundice).

bilirubin metabolism: unconjugated fat-soluble bilirubin is transported to the liver bound to albumin; it is conjugated with glucuronide to the water-soluble form (see Jaundice).

vitamin storage: A, D, K, B12 and folate.

vitamin storage: A, D, K, B12 and folate.

hormone metabolism and inactivation: include cortisol, oestrogens, aldosterone, vasopressin and thyroxine.

hormone metabolism and inactivation: include cortisol, oestrogens, aldosterone, vasopressin and thyroxine.

drug metabolism: achieved by transforming lipid-soluble compounds into water-soluble ones via enzymes located in the hepatocyte microsomes. Several processes are involved, including oxidation, conjugation, reduction, hydrolysis, methylation and acetylation. Most drugs are metabolised by a combination of oxidation by cytochromes and conjugation (see Pharmacokinetics).

drug metabolism: achieved by transforming lipid-soluble compounds into water-soluble ones via enzymes located in the hepatocyte microsomes. Several processes are involved, including oxidation, conjugation, reduction, hydrolysis, methylation and acetylation. Most drugs are metabolised by a combination of oxidation by cytochromes and conjugation (see Pharmacokinetics).

• Effects of anaesthetic agents:

enzyme induction by volatile agents has been reported but is controversial.

enzyme induction by volatile agents has been reported but is controversial.

Liver dialysis. Term used to describe various techniques for extracorporeal detoxification of blood in hepatic failure. Includes the molecular adsorbents recirculation system (MARS) in which a dialysis circuit containing albumin is separated from the patient’s blood by a semipermeable membrane, the albumin filtered in a second circuit before being reused. Single-pass albumin dialysis (SPAD) uses a single disposable circuit containing albumin. Continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration and other variants of haemoperfusion and haemodialysis have also been investigated. Few are in routine use, although MARS was approved in the USA in 2005 for patients awaiting liver transplantation.

Liver failure, see Hepatic failure

Liver function tests. Most commonly measured:

– aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT): released by damaged hepatocytes. Very high levels suggest hepatitis. Normally 5–40 iu/l.

– albumin: reduced in chronic liver disease after a few weeks. Normally 35–55 g/l.

– globulins: increased to varying extents, depending on the underlying cause. Normally 25–35 g/l.

– bromosulfothalein excretion: rate of excretion depends on hepatic function.

Liver transplantation. First performed in 1963. Indicated for end-stage hepatic failure, e.g. due to inherited disease, chronic hepatitis, acute toxic hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis and some cases of liver tumour. Scoring systems are commonly used to prioritise potential recipients, based on the likelihood of death whilst waiting for transplantation. Surgery involves vascular and biliary isolation of the diseased organ (pre-anhepatic and anhepatic phases) with re-anastomosis of a donor cadaveric organ (reperfusion phase); partial donation by live donors is also performed. The recipient’s liver is dissected to its vascular pedicle, the portal vein, hepatic artery and inferior vena cava above and below the liver are clamped, and the diseased organ is removed. Venovenous bypass is often employed from the portal and femoral veins to the axillary or internal jugular veins, although practice varies between centres. Donor liver viability is up to 8 h from harvesting. It is flushed with crystalloid solution via the portal vein to remove the transport infusate and air bubbles. Anastomosis of the portal vein and hepatic artery is followed by release of vascular clamps, incorporating the donor liver into the recipient’s circulation.

as for hepatic failure. Preoperative assessment includes evaluation of cardiovascular status and other co-morbidity. Opioid, volatile agent, neuromuscular blockade and IPPV are usual; N2O is avoided to reduce bowel distension and risk of air embolism during re-anastomosis. Aseptic techniques are used to reduce infection. Ciclosporin and corticosteroids are given.

as for hepatic failure. Preoperative assessment includes evaluation of cardiovascular status and other co-morbidity. Opioid, volatile agent, neuromuscular blockade and IPPV are usual; N2O is avoided to reduce bowel distension and risk of air embolism during re-anastomosis. Aseptic techniques are used to reduce infection. Ciclosporin and corticosteroids are given.

monitoring and vascular lines include direct BP and CVP measurement, pulmonary artery catheterisation (or a non-invasive method of cardiac output measurement), several large iv cannulae, temperature probes and urinary catheter.

monitoring and vascular lines include direct BP and CVP measurement, pulmonary artery catheterisation (or a non-invasive method of cardiac output measurement), several large iv cannulae, temperature probes and urinary catheter.

frequent measurement of plasma electrolytes, glucose, haemoglobin, platelets, arterial blood gases and coagulation studies is required. Thromboelastography is useful.

frequent measurement of plasma electrolytes, glucose, haemoglobin, platelets, arterial blood gases and coagulation studies is required. Thromboelastography is useful.

blood loss is usually 8–10 units but may be up to 200 units. Cell salvage is often used. Rapid blood transfusion devices are required to keep up with losses; they include a reservoir of several units of blood, driven by a pump. Venous return may also be reduced by surgical manipulation.

blood loss is usually 8–10 units but may be up to 200 units. Cell salvage is often used. Rapid blood transfusion devices are required to keep up with losses; they include a reservoir of several units of blood, driven by a pump. Venous return may also be reduced by surgical manipulation.

SVR and cardiac rhythm/output may change frequently. Myocardial depression may be caused by hypocalcaemia, hypothermia and acidosis. Acidosis is common but treated cautiously, as postoperative metabolic alkalosis is also common, due to metabolism of lactate and citrate. Inotropic drugs are often required.

SVR and cardiac rhythm/output may change frequently. Myocardial depression may be caused by hypocalcaemia, hypothermia and acidosis. Acidosis is common but treated cautiously, as postoperative metabolic alkalosis is also common, due to metabolism of lactate and citrate. Inotropic drugs are often required.

hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia may occur, especially during the anhepatic phase.

hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia may occur, especially during the anhepatic phase.

surgery usually lasts 8–10 h but may be up to 24 h, with major biochemical, haematological and temperature disturbances that may persist postoperatively. IPPV is usually maintained for 24–48 h. Postoperative problems include infection, atelectasis and pleural effusion, graft failure, hepatic artery thrombosis, biliary leaks or obstruction, neurological impairment and renal failure.

surgery usually lasts 8–10 h but may be up to 24 h, with major biochemical, haematological and temperature disturbances that may persist postoperatively. IPPV is usually maintained for 24–48 h. Postoperative problems include infection, atelectasis and pleural effusion, graft failure, hepatic artery thrombosis, biliary leaks or obstruction, neurological impairment and renal failure.

Living will, see Advance decision

Local anaesthesia, see Infiltration anaesthesia; Local anaesthetic agents; Regional anaesthesia; Topical anaesthesia; specific blocks

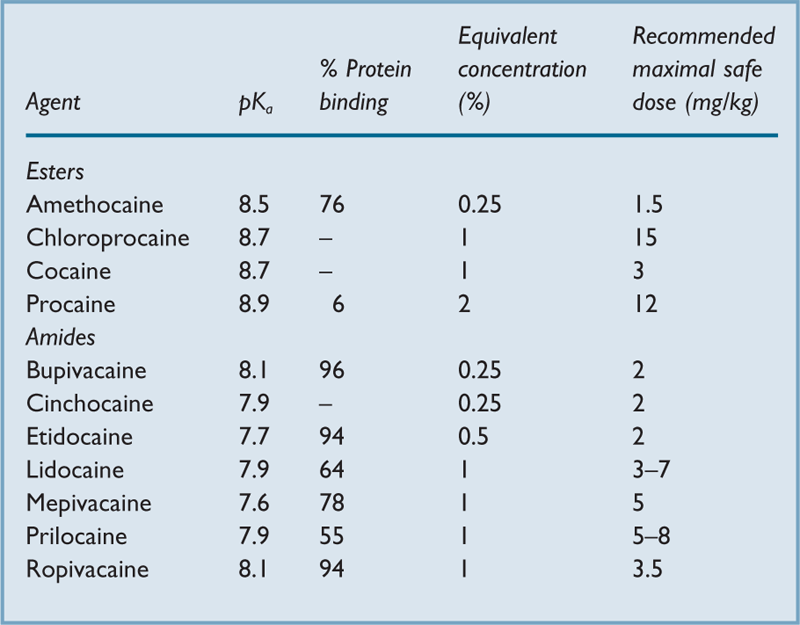

Local anaesthetic agents. cocaine was introduced in 1884 by Freud and Koller; less toxic agents subsequently introduced include procaine and stovaine (1904), cinchocaine (1925), tetracaine (amethocaine) (1931) and lidocaine (lignocaine) (1947). Lidocaine is particularly non-toxic. Later drugs include chloroprocaine (1952), mepivacaine (1956), prilocaine (1959), bupivacaine (1963), etidocaine (1972), articaine (1974), ropivacaine and levobupivacaine (both 1997). Others are used only for topical anaesthesia, e.g. benzocaine.

• General properties (Table 28):

poorly water-soluble weak bases with pKa > 7.4.

poorly water-soluble weak bases with pKa > 7.4.

– esters:

– allergic reactions are common.

– rapidly metabolised by plasma and liver cholinesterase. One metabolite, para-aminobenzoic acid, is thought to be responsible for allergic reactions. Metabolism may be prolonged when plasma cholinesterase level is low, e.g. liver disease, pregnancy or atypical enzymes.

– amides:

– allergic reactions are rare; they may be associated with the preservative vehicle.

presented in solution as acidic hydrochloride salts.

presented in solution as acidic hydrochloride salts.

bind to fast sodium channels in the axon membrane from within, preventing sodium entry during depolarisation. The threshold potential is thus not reached and the action potential of the nerve not propagated (membrane-stabilising effect).

bind to fast sodium channels in the axon membrane from within, preventing sodium entry during depolarisation. The threshold potential is thus not reached and the action potential of the nerve not propagated (membrane-stabilising effect).

– diffuses to axons; thus more effective if deposited close to the nerve (see Minimal blocking concentration).

– dissociates within the axon to the ionised form; thus dependent on intracellular pH.

– binds to sodium channels in their open state.

smallest nerve fibres are blocked first.

smallest nerve fibres are blocked first.

• Features of block are affected by:

patient variables, e.g. age, fitness, pregnancy.

patient variables, e.g. age, fitness, pregnancy.

individual drug characteristics.

individual drug characteristics.

site of injection, e.g. rapid onset of spinal anaesthesia but slow onset of brachial plexus block.

site of injection, e.g. rapid onset of spinal anaesthesia but slow onset of brachial plexus block.

– vasoconstrictors, e.g. adrenaline, felypressin, phenylephrine: reduce systemic absorption and prolong the block. Intensity and onset may be improved. Effects are greatest with local anaesthetics that cause vasodilatation, e.g. lidocaine, and less with prilocaine and bupivacaine. Cocaine itself causes vasoconstriction. Noradrenaline is less effective than adrenaline.

– potassium: has been shown to increase duration of block.

– dextrans: used to prolong blocks, perhaps by combining with local anaesthetic and trapping it within the tissues. Results are inconsistent.

– hyaluronidase: formerly used to increase spread by breaking down tissue stroma. Benefits are doubtful; thus rarely used now except in eye blocks.

– dextrose to increase baricity for spinal anaesthesia: affects spread.

may follow accidental iv injection, or systemic absorption, the latter affected by:

may follow accidental iv injection, or systemic absorption, the latter affected by:

– total dose administered. Recommended maximal ‘safe’ doses are useful as a guide but are rough estimations only, since other factors are involved (see Table 28).

– site of injection: e.g. absorption is large after topical anaesthesia and intercostal block and slow after brachial plexus block and infiltration anaesthesia. Affected by blood flow and tissue vascularity.

due to membrane-stabilising effects on other cells, especially heart and CNS. Features:

due to membrane-stabilising effects on other cells, especially heart and CNS. Features:

– tingling, typically around the mouth and tongue.

– lightheadedness, agitation and tremor.

– unconsciousness and/or convulsions.

– supportive, with oxygenation/cardiovascular support as for CPR.

– lipid emulsion 20%: 1.5 ml/kg bolus over 1 min, repeated up to two times, followed by 15 ml/kg/h increased to 30 ml/kg/h if the CVS is stable. Propofol is not a viable alternative because of the drug’s haemodynamic effects and low concentration of intralipid.

– thiopental or diazepam/midazolam may be used for convulsions, although hypotension may be exacerbated.

other complications may be related to:

other complications may be related to:

– vasoconstrictors, e.g. tachycardia, arrhythmias, pallor, agitation, caused by adrenaline.

– regional technique, e.g. intraneural injection, hypotension following spinal anaesthesia.

– preservatives, e.g. allergic reactions (e.g. to methylparaben), neurological damage and arachnoiditis.

See also, Ionisation of drugs; Regional anaesthesia; specific blocks

Lofentanil cis-oxalate. Opioid analgesic drug derived from fentanyl; developed in 1975. 20 times as potent as fentanyl and 6000 times as potent as morphine in animal studies. Of similar pKa to fentanyl, highly lipophilic and with a particularly long duration of action due to persistent binding to opioid receptors (about 10 h). Has been used via the epidural route to provide long-lasting analgesia, but not generally available.

Logistic organ dysfunction system (LODS). Scoring system developed to predict hospital mortality from 11 variables measured on the first day of admission to ICU (Glasgow coma scale, heart rate, systolic BP, urea, creatinine, urine output, PaO2/FIO2 ratio, white cell count, platelets, bilirubin and international normalised ratio). The total score ranges from zero (normal) to 22.

Has been modified by adding infection as a 12th item (organ dysfunction and/or infection; ODIN).

Keegan MT, Gajic O, Afessa B (2011). Crit Care Med; 39: 163–9

See also, Mortality/survival prediction on intensive care unit

Long, Crawford Williamson (1815–1878). US general practitioner; administered diethyl ether several times for minor surgery from 1842 in Georgia, but did not report it until after Morton‘s demonstration.

Long Q–T syndromes, see Prolonged Q–T syndromes

Lorazepam. Benzodiazepine, used for insomnia, epilepsy, sedation and premedication. Now the initial drug of choice in status epilepticus. Half-life is approximately 12 h with prolonged duration of action. Said to produce more amnesia than other benzodiazepines. Similar rates of absorption follow im and oral administration.

Lower oesophageal sphincter. 2–5 cm portion of oesophagus of increased intraluminal pressure, extending above and below the diaphragm. Opens reflexly during swallowing, and helps to prevent retrograde passage of gastric contents into the oesophagus via:

increased muscle tone: muscle of the sphincter zone, especially the inner circular layer, has higher resting tone than other oesophageal muscle, possibly via increased calcium ion uptake and utilisation.

increased muscle tone: muscle of the sphincter zone, especially the inner circular layer, has higher resting tone than other oesophageal muscle, possibly via increased calcium ion uptake and utilisation.

– vagal: muscle tone reflexively increases as gastric pressure increases, thus maintaining barrier pressure (normally about 20 cmH2O). The reflex is abolished by atropine.

– oesophageal compression by the diaphragm.

– acute angle of entry of the oesophagus into the stomach.

– mucosal flap or rosette at the oesophageal opening.

• Muscle tone is decreased by:

anticholinergic drugs given iv; possibly less with glycopyrronium. Atropine im does not affect sphincter pressure, but inhibits the action of metoclopramide.

anticholinergic drugs given iv; possibly less with glycopyrronium. Atropine im does not affect sphincter pressure, but inhibits the action of metoclopramide.

gut hormones, e.g. vasoactive intestinal hormone, glucagon and gastric inhibitory peptide. Gastrin may increase tone at very high levels.

gut hormones, e.g. vasoactive intestinal hormone, glucagon and gastric inhibitory peptide. Gastrin may increase tone at very high levels.

opioid analgesic drugs, volatile anaesthetic agents and most iv anaesthetic agents.

opioid analgesic drugs, volatile anaesthetic agents and most iv anaesthetic agents.

No change is found with H2 receptor antagonists. Although suxamethonium may increase intragastric pressure, the corresponding increase in lower oesophageal sphincter tone maintains barrier pressure.

Sphincter incompetence may result in gastro-oesophageal reflux. It becomes less competent in hiatus hernia, particularly if intra-abdominal pressure increases, e.g. in the head-down position.

Lown–Ganong–Levine syndrome. Tendency to SVT caused by an accessory conducting pathway bypassing the atrioventricular node. Impulses may pass directly from the atria to the distal heart conducting system, without the usual delay at the node.

Characterised by a normal P wave, short P–R interval and normal QRS complex on the ECG. Anaesthetic management is as for Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome.

Lucid interval. Period of apparently normal function and behaviour following head injury, during which blood is accumulating inside the skull from a slowly bleeding vessel. Classically occurring with extradural haemorrhage, features only become apparent when the collection causes compression of intracranial structures; because this may occur up to several hours after injury, diagnosis may be delayed and significant impairment may result.

Ludwig’s angina. Cellulitis of the floor of the mouth and submandibular region, with massive swelling. Often due to anaerobic infection. May progress to laryngeal obstruction and death unless treated with antibiotics initially, or by deep incision of the tissues under the mandible.

Anaesthetic management is as for airway obstruction; antibiotic therapy may reduce the swelling and improve obstruction preoperatively. Local anaesthesia may be preferable in extreme cases.

Luer connectors. Worldwide system of standard fittings designed to provide leak-free (for air and fluid) connections between syringes, hypodermic needles and three-way taps. The two standard types are Luer-Lok (ends joined securely via a screw thread and matching hub on the male and female connections, respectively) and Luer-Slip (tapered male and female connections held in place by friction). Although originally designed for iv equipment, Luer connections are now present on many others, e.g. nasogastric tubes, airway monitoring tubing, and equipment for spinal and epidural anaesthesia. Fatal wrong-route errors involving the latter (e.g. iv administration of local anaesthetic agents or intrathecal/epidural administration of iv cytotoxic drugs) have led to repeated calls for the development and adoption of non-Luer connector systems, but their introduction has been beset by enormous logistical problems. In 2009, the NPSA called for all spinal equipment to be non-Luer by April 2011 (revised in 2010 to April 2012), but adherence in the NHS has been inconsistent, partly due to difficulties over proper evaluation of the new equipment.

[Hermann W. Luer (1836–1910), German medical instrument maker]

Lumbar epidural anaesthesia, see Epidural anaesthesia

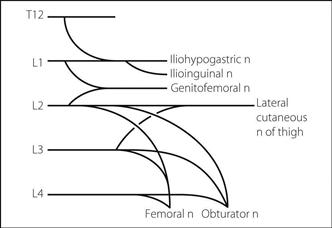

Lumbar plexus. Formed in front of the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae from the anterior primary rami of the first four lumbar nerves, occasionally with a contribution from T12 (Fig. 102).

May be blocked via paravertebral, psoas compartment, fascia iliaca compartment and ‘three-in-one’ femoral nerve blocks. Individual nerves may also be blocked. Block is useful for hip surgery and operations on the thigh and anterior gluteal region, together with adjacent perineal and suprapubic areas.

See also, Inguinal hernia field block

Fig. 102 Plan of the lumbar plexus

Lumbar puncture. Procedure for removing CSF either for diagnostic purposes (e.g. meningitis) or treatment (e.g. benign intracranial hypertension, intrathecal injection of chemotherapy, CSF filtration). First performed by Quincke for the treatment of hydrocephalus. Forms part of the procedure of spinal anaesthesia. May be required in the ICU for diagnosis of neurological conditions. Technique, contraindications and complications are as for spinal anaesthesia but without the drug effects; CSF ‘opening pressure’ may also be measured, using a simple manometer. Neurologists, general physicians and radiologists are more likely to use larger needles with cutting points than anaesthetists; whether subsequent post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is masked by the presenting symptoms is uncertain. The incidence of PDPH may be decreased if the stylet is reinserted after aspiration before removal of the needle, presumably by preventing avulsion of dural strands sucked into the needle’s shaft during removal of CSF.

Lumbar sympathetic block. Performed for peripheral vascular disease, including incipient gangrene, and in chronic pain management (e.g. post-traumatic dystrophies).

With the patient in the lateral position and with a soft pillow between the iliac crest and costal margin to curve the spine laterally, skin wheals are raised 5–8 cm lateral to the upper borders of the spinous processes of L2–4. A 12–18 cm long needle is directed medially, to strike the transverse process at about 3–5 cm. The lateral aspect of the vertebral body is contacted usually 4–6 cm deeper, and the needle advanced a further 1–2 cm. Correct positioning is confirmed by negative aspiration for CSF or blood, and radiographic imaging: the needles should barely reach the anterior borders of the vertebral bodies in the lateral view, and should overlie their lateral edge in the anteroposterior view. Further confirmation of positioning is made by injecting contrast medium. 25–30 ml local anaesthetic solution (e.g. 0.5% lidocaine or prilocaine) is injected at L2, or 15 ml at L2 and L4. Catheters may be inserted for repeated injection. Phenol or absolute alcohol is used for chemical sympatholysis, 3 ml at each of L1, L2 and L3. The block may also be performed with patient prone.

Similar blocks have been performed in the thoracic region but with risk of pneumothorax.

Lundberg waves, see Intracranial pressure monitoring

Lundy, John Silus (1894–1973). US anaesthetist; he became head of department at the Mayo Clinic in 1924. Co-founder of the American Board of Anesthesiology. An advocate and developer of regional techniques, balanced anaesthesia, thiopental and post-anaesthetic recovery rooms. Established the first blood bank in the USA.

• Anatomy:

cone-shaped, with bases applied to the diaphragm.

cone-shaped, with bases applied to the diaphragm.

enveloped in pleura, attached to the mediastinum at the hila.

enveloped in pleura, attached to the mediastinum at the hila.

lobes are divided into segments (see Tracheobronchial tree).

lobes are divided into segments (see Tracheobronchial tree).

– as for pleura, except for the lower border, which lies two ribs cranial to the caudal pleural limit.

• Blood supply: via bronchial and pulmonary arteries (see Pulmonary circulation).

• Nerve supply: sympathetic and vagal plexuses; sensory pathways are mainly via the latter.

synthesis of associated phospholipids, e.g. surfactant, carbohydrates (e.g. mucopolysaccharides) and proteins (e.g. collagen).

synthesis of associated phospholipids, e.g. surfactant, carbohydrates (e.g. mucopolysaccharides) and proteins (e.g. collagen).

metabolism and deactivation of certain compounds, e.g. angiotensin, bradykinin and 5-HT. Takes up amide local anaesthetic agents.

metabolism and deactivation of certain compounds, e.g. angiotensin, bradykinin and 5-HT. Takes up amide local anaesthetic agents.

synthesis and release of compounds, e.g. prostaglandins and histamine.

synthesis and release of compounds, e.g. prostaglandins and histamine.

involvement in the immune system and possibly coagulation.

involvement in the immune system and possibly coagulation.

acts as a reservoir for blood; the pulmonary circulation contains 500–900 ml blood.

acts as a reservoir for blood; the pulmonary circulation contains 500–900 ml blood.

See also, Alveolus; Lung … ; Pulmonary …

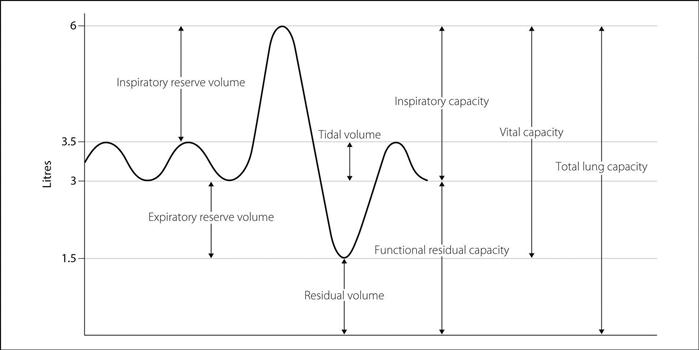

– measurement of static lung volumes: cumbersome apparatus is required. Dead space and closing capacity may be measured.

– assessment of forced expiration and derived variables (e.g. FEV1, FVC, forced expiratory flow rate), e.g. using a spirometer. The FEV1/FVC ratio typically is reduced in obstructive lung disease, and is normal or high in restrictive disease. Peak expiratory flow rate is another simple bedside test for obstructive disease. Reversibility of obstructive disease is assessed using inhaled bronchodilator drugs. Airway reactivity is assessed by challenging with histamine or methacholine whilst measuring FEV1.

– flow–volume loops require more sophisticated apparatus, with instantaneous flow rate measurement.

– airway resistance itself may be measured, and lung compliance.

– maximal voluntary ventilation is non-specific and related to effort as well as pulmonary function.

– respiratory muscle function may be assessed, e.g. maximal mouth or nasal sniff pressures when breathing against a closed valve. Work of breathing and O2 consumption may also be measured.

– blood gas interpretation and pulse oximetry.

– diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (transfer factor); now thought to be related more to  mismatch than to diffusion impairment.

mismatch than to diffusion impairment.

– distribution of ventilation and perfusion as for  mismatch.

mismatch.

pulmonary circulation: assessment is difficult. Radioisotope scanning may be used as for

pulmonary circulation: assessment is difficult. Radioisotope scanning may be used as for  mismatch.

mismatch.

control of breathing: CO2 response curve or response to hypoxia may be used.

control of breathing: CO2 response curve or response to hypoxia may be used.

Lung protection strategies. Principles of mechanical ventilation demonstrated to improve outcomes in acute lung injury. Components include: