CHAPTER 45 Kyphoplasty

INTRODUCTION

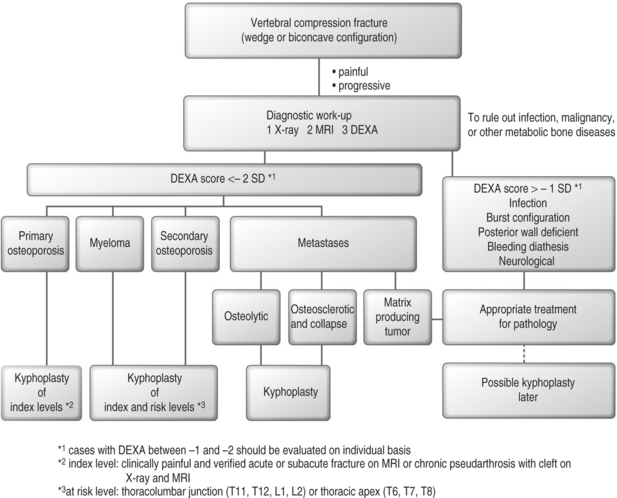

The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates that over 100 million people worldwide, and nearly 30 million in the United States, are at risk to develop fragility fractures secondly to osteoporosis. In the United States there are an estimated 700 000 pathological vertebral body compression fractures each year, of which over one-third become chronically painful (Fig. 45.1).1,2 Although the standard of care for most other fragility fractures including hip and wrist fractures is immediate reduction and stabilization, vertebral body compression fractures are traditionally treated with medical modalities and only rarely treated with surgical modalities (Fig. 45.2). This benign neglect arose because open surgical repair of these fractures was too invasive, with poor outcomes. Unfortunately, the medical management of painful fractures (bed rest, hospitalization, narcotic analgesics, and bracing) does nothing to restore spinal alignment and may compound the problem. Just as unfortunate and due to its inherent risks, invasive nature, and the poor quality of osteoporotic bone, surgical treatment of vertebral body compression fractures has traditionally been limited to cases where there is concurrent spinal instability or neurologic deficit.

In response to the limited results of medical and surgical modalities, to stabilize and strengthen the collapsed vertebral bodies, interventional neuroradiologists, first in France and now the US, initiated percutaneous bone cement injections.3,4 Direct cement injection or ‘vertebroplasty’ has been shown to reduce fracture pain. Vertebroplasty, however, does not address the spinal deformity. Also, this technique requires a forced cement injection using low-viscosity, slow-curing cement, thus increasing the risk of cement leaks through the fracture clefts or the venous sinuses.

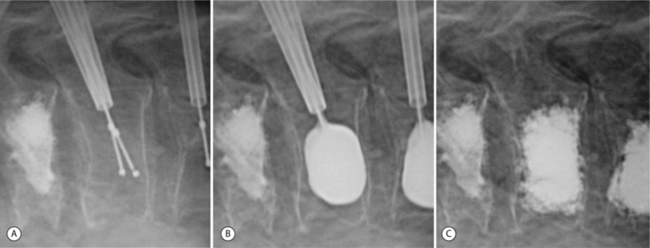

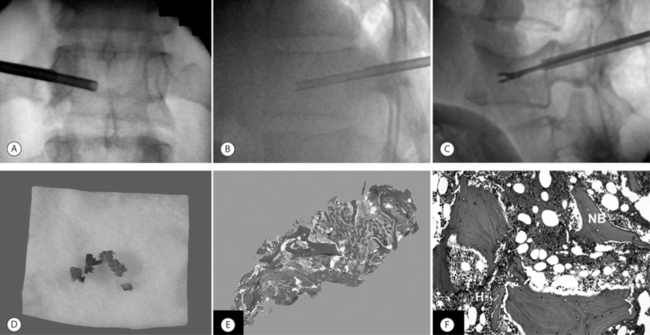

‘Kyphoplasty’ is a minimally invasive technique for the treatment of osteoporotic or osteolytic painful progressive vertebral wedge compression fractures (VCFs). This technique has a number of benefits and potential advantages over traditional medical and surgical treatment modalities for VCFs. It involves the introduction of a cannula into the vertebral body, followed by insertion of an inflatable bone tamp (IBT) designed to elevate the endplates and reduce the vertebral body back towards its original height, while creating a cavity to be filled with bone cement (Fig. 45.3). By reducing the vertebral body back towards its native height the sagittal alignment of the spine is restored, providing patients with cosmetic and functional improvement.5–7 This also acts to potentially protect other levels from collapse by alleviating the force transmission associated with a kyphotic posture.8,9 By creating a cavity the cement augmentation is performed with more control by depositing into the preformed cavity partially cured cement, thereby reducing the risk of cement extravasation. By stabilizing the vertebral body, pain from the progressive fracture collapse or altered biomechanics can be minimized or even eliminated. The first kyphoplasty was performed in August, 1998, and up to January, 2004, over 30 000 patients in the United States have had kyphoplasty procedures for over 40 000 fractures. In preliminary reports well over 90% of patients attained significant pain relief. The data from the recent published reports also indicate that kyphoplasty has a significant positive effect on spinal malalignment and patient quality of life.5–7

INDICATIONS

Kyphoplasty is currently indicated for progressive, painful osteoporotic or osteolytic vertebral body wedge compression fractures. Similar to any other fragility fracture the goals are to restore stability, anatomical alignment, and function as soon as safely possible. Even though the quoted natural history of vertebral compression fractures is for two-thirds of the patients to eventually become pain free, one must appreciate that not one of those vertebral bodies ever regains its normal height, and that the presence of a vertebral collapse predicts both increased mortality and a fivefold increase in further fractures at adjacent or remote levels within 1 year.10–12 If one subscribes to the philosophies of spinal biomechanics and appreciates that ‘kyphosis begets kyphosis,’ especially in the face of low bone density, then it only makes sense to intervene before the deformity progresses significantly, in order to minimize the effects of sagittal imbalance on the spine. Pain relief then becomes the secondary indication and protection of sagittal spinal alignment becomes the primary indication. The results of vertebral augmentation seem most predictable with immediate intervention.

CONTROVERSIES

There exists a certain level of debate regarding the number of levels to augment and the indication for prophylaxis in the setting of vertebral compression fractures. Vertebroplasty proponents are more liberal in recommending multiple levels at any one time. One must, however, consider the volume of cement and the potential for monomer toxicity. It is well established that cement monomer is arrythmogenic and cardiotoxic at the volumes used for a total hip or knee replacement. The risk appears to be somewhere in the neighborhood of 1 in 3000 to 1 in 5000.13,14 Taking into account the volume of cement (6 cc per level) and the direct access to the cardiovascular system, and then assuming one is willing to accept the same degree of risk, then it seems most appropriate to limit vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty to one or two levels at any surgical setting. Kyphoplasty does have a built-in advantage to vertebroplasty in that the technique dictates a thicker partially cured cement be poured into the cavity in a controlled fashion rather than a highly liquid cement forced into the closed space of the collapsed vertebral body. The liquid cement of vertebroplasty has more free monomer available to enter the circulation and the liquid cement will obey the laws of fluid dynamics seeking out the path of least resistance, thus readily entering the venous sinuses or exiting through the vertebral body fissures and cracks, resulting in more cement leaks.

EVIDENCE-BASED OUTCOMES

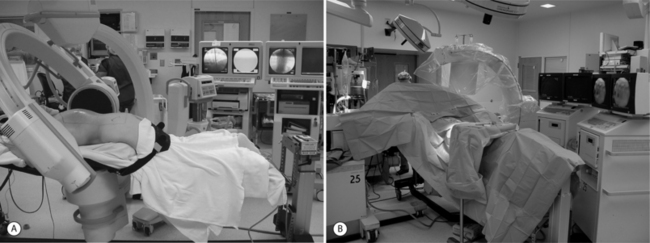

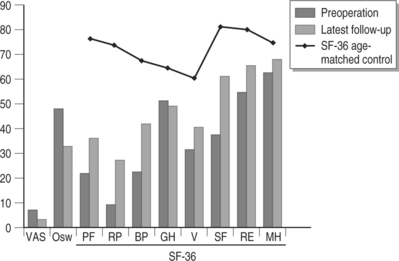

In the authors’ ongoing Institutional Review Board approved study,5–7 over 900 consecutive kyphoplasty procedures were performed in over 300 patients between April, 1999, and February, 2004. The mean age was 69 years (range 35–89). The mean duration of symptoms was 7 months. Outcome data were obtained by administering the Short Form-36 health survey (SF-36) and visual analog scale (VAS) for pain rating; additionally, the patients underwent detailed neurological and radiographical examinations pre- and postoperatively (Fig. 45.4). Perioperative and clinical follow-up revealed that the procedure was well tolerated with improvement in pain and early mobilization. The levels treated ranged from T3 to L5 with 47% of the vertebrae at thoracolumbar junction. Length of stay ranged from 0.5 day to 9 days (mean 1.1 day). In the experience of the authors there were no clinically significant cement leaks and no perioperative complications attributable to the inflatable bone tamp or tools. Pre- and postoperative SF-36 data are available on over 230 patients (72%) with follow-up ranging from 1 week to 59 months (mean 14 months). SF-36 scores improved in every category, statistically significant in all but the general health modality. Physical function improved from 22.0 to 36.0 (p=0.0001). Role physical improved from 9.3 to 27.3 (p=0.0001). Bodily pain improved from 22.4 to 41.9 (p=0.0001). Vitality improved from 31.4 to 40.7 (p=0.0001). Social function improved from 37.7 to 61.2 (p=0.0001). Role emotional improved from 54.8 to 65.5 (p=0.030). Mental health improved from 63.1 to 68.0 (p<0.001). General health was unchanged from 51.3 to 49.2 (p=0.067). The VAS scores improved from a preoperative level of 7.0 to an initial postoperative level of 3.2 (p<0.0001). At last follow-up examination, the value remained unchanged at 3.4 (p<0.0001). With regard to height restoration, a mean vertebral body height restoration of 46.8% (midline measurement) in 70% of 70 treated levels was reported in the initial study.7

Garfin et al. reported in a prospective multicenter series that the average anterior and midline height were 83±14% and 76±14% before treatment, respectively, that were increased to 99±13% and 92±11% after the treatment, respectively. In vertebral bodies with 15% or more of the estimated height lost, the average anterior and midline height were 68±12% and 64±13% before treatment, respectively, that improved to 84±14% and 90±12% after the treatment, respectively.15

Ledlie et al. reported functional and radiographic outcomes in their first 96 kyphoplasty patients with 133 fractures.16 Their follow-up period was a minimum of 12 months and the mean patient age at the time of surgery was 76 years (range 51–93). With regard to pain as rated by the patient using a 10-point VAS, the mean score was decreased to 1.4 at the 1-year follow-up, while the mean preoperative VAS score was 8.6. Ambulatory status was also improved postoperatively. Over 90% of the patients (27/29, with 1-year follow-up) were ambulatory at 1 year, while only 35% of the patients (28/79) were ambulatory preoperatively. In this study vertebral body height restoration was reported from radiographic measures of anterior and midline points of the fractured vertebrae using the two nearest normal vertebrae as reference points. At 1 year, the anterior vertebral height was 85% of the predicted height and midline height was 89%, while their preoperative heights were 66% and 65%, respectively.16

Phillips et al. also recently reported their early radiographic and clinical results of kyphoplasty17 In this study, 29 patients with 61 fractures between T6 to L5 were evaluated. The mean age of these 29 patients was 70 years. Their clinical information including pain relief, improvement in activity, and satisfaction with the surgical procedure as well as their sagittal spinal alignment on the standing radiographs were assessed and followed up to 1 year. Average pain scores were significantly decreased to 2.6 and 0.6, at 1 week and 1 year, respectively, while average pain score was 8.6 preoperatively. Local kyphosis was improved by a mean of 14 degrees in patients with reducible fractures.17

COMPLICATIONS

In the authors’ series of patients,5,7 cement extravasation was seen in less than 10% of cases. No problems were identified clinically immediately after surgery or at final follow-up as a result of these extravasations. In one patient a myocardial infarction occurred as a result of fluid overload during the procedure. In a separate prospective multicenter series reported by Garfin and Reilley, there were six major complications out of 600 cases associated with the kyphoplasty procedure. Four of these were neurologic complications (0.75%).18 These were directly attributable to surgeon error and breach of technique. To date, no reports of primary or secondary infection of the cement mantle have been published.

Ledlie et al. reported that asymptomatic cement leaks were noted in 9% of vertebral bodies treated, but no device- or procedure-related complications were reported.16

Phillips et al. reported that asymptomatic cement leaks were observed in 6 of 61 vertebral fractures (9.8%).17 In this series as well there were no clinical consequences attributable to the bone tamp or cement deposition.

BIOPSY RESULTS

A diagnostic bone biopsy can be easily performed during a kyphoplasty procedure and does not affect the safety of the procedure if done appropriately (Fig. 45.5). The authors histologically evaluated 178 biopsies obtained from 142 patients during 246 kyphoplasty procedures. These showed partially necrotic fragments of bone as well as areas of fibrosis and variable stages of woven bone, suggesting ongoing fracture healing.19 The specimens obtained from 30 patients (21%) showed marked increased osteoid in undecalcified sections. These thickened osteoid seams may suggest possible mineralization defect (osteomalacia). Osteoid can be increased either because of increased bone remodeling activity or because of a mineralization defect. Tetracycline labeling is the method of choice to distinguish between these two diagnoses. Careful administration of tetracycline labels may help identify any correlation between vertebral fracture and osteomalacia. Also in this series, the biopsies of 4 patients provided a definite diagnosis of plasma cell dyscrasia in otherwise unsuspected or unknown spinal lesions. These findings suggest that a biopsy is useful for all initial vertebral augmentation cases to rule out any occult lesions.

HISTOLOGY OF HUMAN RETRIEVED SPECIMENS

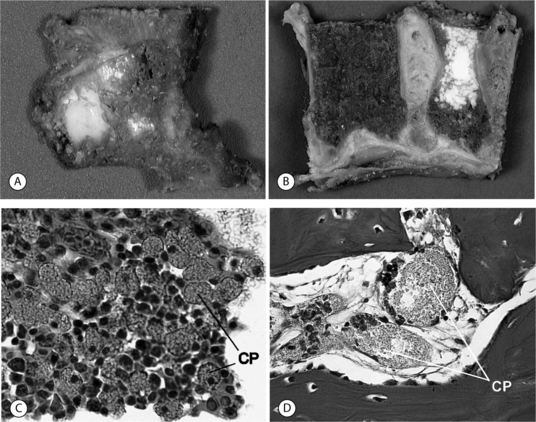

In spite of reported good clinical results, several aspects of the kyphoplasty procedure are controversial, including the optimum methods of mixing and depositing the cement, the potential importance of a foreign body reaction at the cement–bone interface, efficacy of bone tamp usage, the use of relatively high concentrations of radiopaque agents and antibiotics in the cement, and the clinical indications for the procedure. The authors were able to document histologically four vertebral bodies from two cases 1 month and 2 years after cement augmentation, after a surgical corpectomy and at an autopsy (Fig. 45.6).20 In this study the histology of vertebrae treated using the kyphoplasty technique revealed a dense cancellous shell around the cement mantle. This suggests that the tamping had displaced bone, essentially autografting the space around the cement. Bone immediately around the cement did not show extensive necrosis. However, foreign body giant cells contained material consistent with cement particles and/or barium sulfate. Particles were also identified within vascular spaces. Further histologic evaluation may help clarify the safety and efficacy of kyphoplasty.

INCIDENCE OF ADJACENT AND REMOTE FRACTURES

One issue continuously raised by spine practitioners regards the incidence of remote and adjacent-level vertebral compression fractures after an index vertebral compression fracture has been augmented by either vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty. Keller et al. investigated the biomechanics of age-related spinal deformity using a sagittal plane finite element analysis model and showed that postural forces were responsible for initiation and propagation of osteoporotic spinal deformity in the elderly.21 Kayanja et al. reported their results of biomechanical tests for cadaveric thoracic wedge compression fractures and showed that anterior cortical strain was concentrated at the apex of a thoracic kyphotic curve and the vertebral body immediately above it had the next highest strain with an increased risk of secondary fracture.22 Moreover, Hasserius et al. reported a Swedish cohort, in a 10-year population based study of 598 individuals, and suggested a prevalent vertebral deformity could predict both increased mortality and increased fracture incidence during the following decade in both men and women.12 Left untreated, the incidence of subsequent vertebral fracture after an index fracture is reported in other studies as approximately 20%.10,11

From the vertebroplasty literature, only one study reported a 52% rate of remote or adjacent level fractures after vertebroplasty.23

From the kyphoplasty literature, Harrop et al. reported that the incidence of postkyphoplasty vertebral compression fracture in the primary osteoporotic patients was 11.25% (9 fractures/80 patients), while the incidence in the steroid-induced osteoporotic patients was 48.6 % (17 fractures/35 patients).9

The above results imply that the intervention, kyphoplasty, in primary osteoporotic patients may not increase the rate of remote or adjacent level fractures compared to the published natural history reports. These results also imply that the secondary osteoporotic patients are in fact at increased risk compared to primary osteoporotic patients for subsequent vertebral compression fractures although there is no natural history benchmark to which this rate can be compared.

KYPHOPLASTY FOR MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Multiple myeloma is a monoclonal proliferation of malignant plasma cells that usually affects the bone marrow. Excessive bone resorption due to an increase of proinflammatory cytokines is a characteristic feature of the disease.24 Grossly, this tumor is a very soft vascular tumor, as evidenced by the backflow of blood from the working cannulae during kyphoplasty. The near-fluid consistency of the tumor and the lytic nature of the bone make it easy for the inflatable bone tamp to displace tissue in the act of reducing the fracture and creating the cavity. This then results in impressive cement filling of the vertebra. Dudeney et al. reported satisfying results in the treatment of osteolytic vertebral compression fractures due to multiple myeloma.6 As of February, 2004, the authors treated 80 myeloma patients using the kyphoplasty method. The mean age of patients was 60.6 (range 35–82) years. There were no major complications related directly to use of this technique. Pre- and postoperative SF-36 data were available on 61 patients (75.3%) with follow-up ranging from 6 weeks to 59 months (mean 15.6 months). Significant improvement in SF-36 scores occurred for bodily pain: 23.0 to 44.4 (p<0.0001) and physical function: 25.5 to 36.6 (p=0.034), vitality: 30.3 to 38.1 (p=0.039), and social function: 35.4 to 67.5 (p=0.0002). Mental health improved from 60.3 to 66.2 (p=0.0009). Role emotional was unchanged from 54.6 to 63.0 (p=0.086). General health was unchanged from 51.2 to 49.0 (p=0.084). These results suggest that the kyphoplasty technique is efficacious in the treatment of osteolytic vertebral compression fractures due to multiple myeloma, and associated with early clinical improvement of pain and function as well as some restoration of vertebral body height in these patients. The effects of potential tumor dissemination, in what is already widespread disease, is not known. Significant systemic effects are not suspected and have not been noted by the authors in this initial group.6,25

KYPHOPLASTY FOR SPINAL METASTASES

In an ongoing evaluation of kyphoplasty for spinal metastases, the results have remained very favorable.25 From April, 1999, to February, 2004, the authors treated 21 patients of spinal metastases (9 breast, 4 leukemia/lymphoma, 3 lung, 5 unknown origin). All patients had painful compression fractures secondary to a metastatic lesion to the spine. The kyphoplasty procedure was successfully performed in all 21 patients. The perioperative and clinical follow-up revealed that the procedure was well tolerated with improvement in pain and early mobilization. Pre- and postoperative SF-36 data were available on 14 patients (66.7 %) with follow-up ranging from 3 weeks to 206 weeks (mean 44.9 weeks). Physical function improved from 20.9 to 33.5 (p=0.036). Vitality improved from 31.2 to 42.9 (p=0.012). Social function improved from 37.5 to 66.1 (p=0.011). Role physical improved from 12.5 to 19.6 (p=0.59). Bodily pain improved from 31.6 to 39.0 (p=0.24). Mental health improved from 60.0 to 62.0 (p=0.69). Role emotional decreased from 55.6 to 51.3 (p=0.77). General health decreased from 52.1 to 46.0 (p=0.73). The VAS improved from 6.5 to 3.9 (p=0.15).

Barr et al. reported their results with osteolytic metastatic vertebral collapse in eight patients and revealed that only four patients experienced any pain relief. In this group of patients there was a 6% complication rate.26

Fourney et al. reported their results of vertebroplasty and/or kyphoplasty for painful vertebral body fractures in cancer patients.27 Asymptomatic cement leakage occurred during vertebroplasty at 6 (9.2%) of 65 levels, while no cement extravasation was seen during kyphoplasty in this study. The mean percentage of restored vertebral body height by kyphoplasty was 42±21%.

1 Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, et al. Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985–1989. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:221-227.

2 Riggs BL, Melton LJ3rd. The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone. 1995;17:505S-511S.

3 Galibert P, Deramond H, Rosat P, et al. [Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral angioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty]. Neurochirurgie. 1987;33:166-168.

4 Jensen ME, Evans AJ, Mathis JM, et al. Percutaneous polymethylmethacrylate vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral body compression fractures: technical aspects. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1897-1904.

5 Coumans JV, Reinhardt MK, Lieberman IH. Kyphoplasty for vertebral compression fractures: 1-year clinical outcomes from a prospective study. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:44-50.

6 Dudeney S, Lieberman IH, Reinhardt MK, et al. Kyphoplasty in the treatment of osteolytic vertebral compression fractures as a result of multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2382-2387.

7 Lieberman IH, Dudeney S, Reinhardt MK, et al. Initial outcome and efficacy of ‘kyphoplasty’ in the treatment of painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Spine. 2001;26:1631-1638.

8 Kayanja MM, Ferrara LA, Lieberman IH. Distribution of anterior cortical shear strain after a thoracic wedge compression fracture. Spine J. 2004;4:76-87.

9 Harrop JS, Prpa B, Reinhardt MK, et al. Primary and secondary osteoporosis’s incidence of subsequent vertebral compression fractures after kyphoplasty. Spine. 2004;29:2102-2105.

10 Lindsay R, Silverman SL, Cooper C, et al. Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA. 2001;285:320-323.

11 Silverman SL. The clinical consequences of vertebral compression fracture. Bone. 1992;13(Suppl 2):S27-S31.

12 Hasserius R, Karlsson MK, Nilsson BE, et al. Prevalent vertebral deformities predict increased mortality and increased fracture rate in both men and women: a 10-year population-based study of 598 individuals from the Swedish cohort in the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:61-68.

13 Charnley J. Systemic effects of monomer. In: Acrylic cement in orthopaedic surgery. London: E. & S. Livingstone; 1970:72-78.

14 Coventry MB, BeckenBaugh RD, Nolan DR, et al. 2,012 total hip arthroplasties: A study of postoperative course and early complications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:273-284.

15 Garfin SR, Yuan HA, Reiley MA. New technologies in spine: kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for the treatment of painful osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine. 2001;26:1511-1515.

16 Ledlie JT, Renfro M. Balloon kyphoplasty: one-year outcomes in vertebral body height restoration, chronic pain, and activity levels. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:36-42.

17 Phillips FM, Ho E, Campbell-Hupp M, et al. Early radiographic and clinical results of balloon kyphoplasty for the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Spine. 2003;28:2260-2265.

18 Garfin SR, Reilley MA. Minimally invasive treatment of osteoporotic vertebral body compression fractures. Spine J. 2002;2:76-80.

19 Togawa D, Bauer TW, Lieberman IH, et al. Occult osteomalacia and myeloma in patients with osteoporotic compression fractures. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:S3.

20 Togawa D, Bauer TW, Lieberman IH, et al. Histological evaluation of human vertebral bodies after vertebral augmentation with polymethyl methacrylate. Spine. 2003;28:1521-1527.

21 Keller TS, Harrison DE, Colloca CJ, et al. Prediction of osteoporotic spinal deformity. Spine. 2003;28:455-462.

22 Kayanja MM, Ferrara LA, Lieberman IH. Distribution of anterior cortical shear strain after a thoracic wedge compression fracture. Spine J. 2004;4:76-87.

23 Grados F, Depriester C, Cayrolle G, et al. Long-term observations of vertebral osteoporotic fractures treated by percutaneous vertebroplasty. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:1410-1414.

24 Lecouvet FE, Vande Berg BC, Maldague BE, et al. Vertebral compression fractures in multiple myeloma. Part I. Distribution and appearance at MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;204:195-199.

25 Lieberman I, Reinhardt MK. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for osteolytic vertebral collapse. Clin Orthop. 2003;415(Supplement):S176-S186.

26 Barr JD, Barr MS, Lemley TJ, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for pain relief and spinal stabilization. Spine. 2000;25:923-928.

27 Fourney DR, Schomer DF, Nader R, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for painful vertebral body fractures in cancer patients. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:21-30.