4 Knowing what works best

A ‘PHOG’ approach

and made me feel comfortable. However I quickly noticed something peculiar; the academic attitudes of the researchers seemed to change when educational issues were discussed. Critical appraisal and scientific scrutiny were suddenly replaced by personal experiences and beliefs and sometimes by traditional values and dogmas.’

What is evidence?

• Your own personal experience. As a professional you should inquire into what works for you in your own setting and how the teaching and learning process could be improved.

• The experience and examples of colleagues. A key factor in the introduction of the OSCE into medical schools in South Africa was the participation and experiences by teachers as external examiners in an OSCE in another school.

• Experiences reported in the literature or presented at educational meetings. Paul Worley described how eight students at Flinders Medical School in Australia received their clinical training in a rural community rather than in a teaching hospital and how they performed in the end of course assessment as well as or better than their colleagues. Despite the relatively small number of students studied, this provided useful evidence and encouragement for teachers interested in developing community-based teaching in their own school.

• A published review, guide or editorial on a topic. The Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) guide on Faculty Development by Michelle McLean and co-workers (2008), for example, provides a helpful summary of experiences with faculty development and how faculty development programmes are best delivered.

• A systematic review. Systematic reviews, such as those published by the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) collaboration (www.BEMEcollaboration.org), use a systematic and transparent methodology and draw on the collective findings from primary research in specific topics to better inform education practice. The BEME systematic review on simulation, for example, identified ten features that improve learning when high fidelity simulators are used.

Evaluating evidence

The QUESTS criteria for the assessment of evidence have been described (Harden et al 1999). These may be of help when you think about the value of evidence you identify:

• The Quality of the evidence. This relates to the type of evidence or research method and the rigour of the study. Qualitative methods have a place alongside quantitative approaches. The randomised controlled trial may in practice not yield the best evidence.

• The Utility of the evidence. The utility is the extent to which the approach described in the research studies will need to be adapted for use in your own practice. Research on problem-based learning (PBL) for example may be based on a small group size of eight students who meet formally as a group three times per week. The results and conclusions may have to be interpreted with caution if your group size is significantly larger and the meetings less frequent.

• The Extent of the evidence. The number of studies reported and the size or extent of the individual studies are relevant. Evidence from a single case study that a new approach has worked well is helpful but it is useful to have this confirmed.

• The Strength of the evidence. It is important to distinguish between statistical significance and practical significance.

• The Target. This relates to whether what has been assessed as the outcome in a research study matches your own expected outcomes. The evidence may be less relevant because the study addresses a different question from the one in which you are interested. You might be interested for example in the costs and logistics of implementing a new assessment procedure while the reported research has, as its aim, an evaluation of the effect of the assessment on the students’ learning.

• The Setting or context for the study. Geographical considerations or the phase of the curriculum may be important factors when interpreting any results. There is no such thing as context-free evidence and research findings need to be interpreted in relation to the context in which the research studies were conducted.

Best evidence medical education

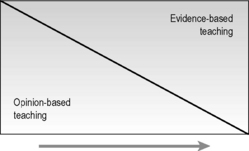

The level of evidence available to inform decisions about day-to-day practice will vary. We are certainly not at the extreme right end of the evidence continuum shown in Figure 4.2, nor are we at the left end. As we learn more and more about what we do as teachers there will be a move towards the right.

Reflect and react

1. With regard to your teaching, consider where you are on the continuum between opinion-based and evidence-based approaches, as shown in Figure 4.2, and whether you might move further to the right.

2. Look at a BEME review, for example BEME review No.4 on Simulation, and assess whether the conclusions have any relevance to your own teaching.

3. The next time you read an article, assess the implications of the evidence for your own practice in terms of the QUESTS criteria.

Haig A., Dozier M. Systematic Searching for Evidence in Medical Education. BEME Guide No. 3. Dundee: AMEE, 2003.

A valuable guide to searching the literature for evidence in medical education.

Harden R.M., Grant J., Buckley G., Hart I.R. Best Evidence Medical Education. BEME Guide No. 1. Dundee: AMEE, 1999.

Issenberg S.B., McGaghie W.C., Petrusa E.R. Features and Uses of High-fidelity Medical Simulations That Lead to Effective Learning. BEME Guide No. 4. Dundee: AMEE, 2004.

Atkinson T., Claxton G. Intuitive Practitioner: On the Value of Not Always Knowing What One is Doing. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2000.

An account of the importance of intuition in a teacher.

McLean M., Cilliers F., Van Wyk J.M. Faculty development: yesterday, today and tomorrow. AMEE Guide No 33. Med. Teach. 2008;30:555-584.

Frameworks for designing, implementing and evaluating faculty development programmes.