KNEE

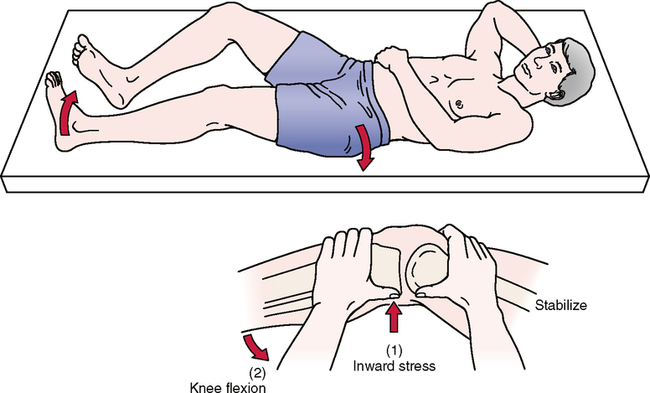

SPECIAL TESTS FOR ONE-PLANE MEDIAL INSTABILITY

Relevant Special Tests

Relevant Signs and Symptoms

• Mild to moderate knee pain is present.

• The patient reports feeling a tearing in the knee, not a “pop.”

• Bruising in the medial knee often is present, because the MCL/TCL is an extra-articular structure.

• Swelling builds up slowly over several days.

• The patient walks with a limp and has pain on knee extension, because extension stretches the ligament.

• Instability and “giving way” may be noted.

• Loss of knee motion and moderate stiffness may be present.

• Medial joint line pain or pain where the ligament attaches to the femur or tibia may be reported.

SPECIAL TESTS FOR ONE-PLANE LATERAL INSTABILITY

Relevant Special Tests

Epidemiology and Demographics

Injury to the LCL/FCL is the least common knee ligament injury. Injuries to the LCL/FCL are rare, accounting for only 2% of all knee injuries. The LCL/FCL is the least likely knee ligament to be sprained, because most LCL/FCL injuries are caused by a blow to the inside of the knee, and that area usually is shielded by the opposite leg.6,7,9–11

Relevant Signs and Symptoms

• Mild to moderate knee pain is present.

• The patient may report feeling a pop in the knee.

• Loss of knee motion and moderate stiffness are present.

• Lateral joint line pain may be reported.

• Bruising in the lateral knee often is present, because the LCL/FCL is an extra-articular structure.

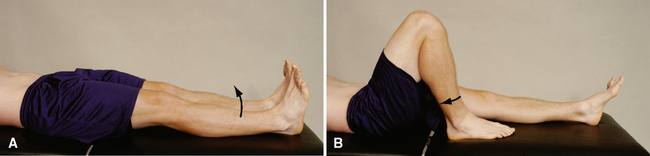

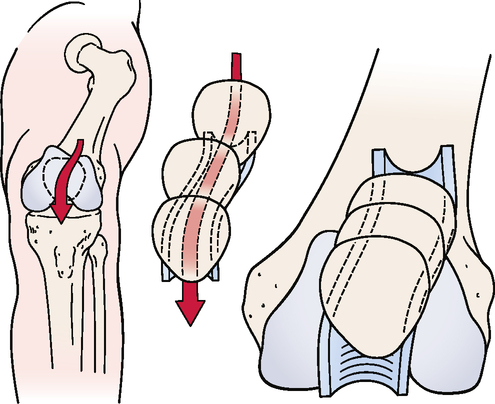

SPECIAL TESTS FOR ONE-PLANE POSTERIOR INSTABILITY

Relevant Special Tests

Posterior sag sign (gravity drawer test)

Drawer sign (see Special Tests for One-Plane Anterior Instability)

Active drawer test (see Special Tests for One-Plane Anterior Instability)

Relevant Signs and Symptoms

Mechanism of Injury

Hyperextension alone may lead to an avulsion injury of the PCL from the origin; this kind of injury may be amenable to repair. An anterior force to the anterior tibia in a hyperextended knee with the foot planted results in combined injury to the knee ligaments, along with knee dislocation.5–7,10,11,14–17

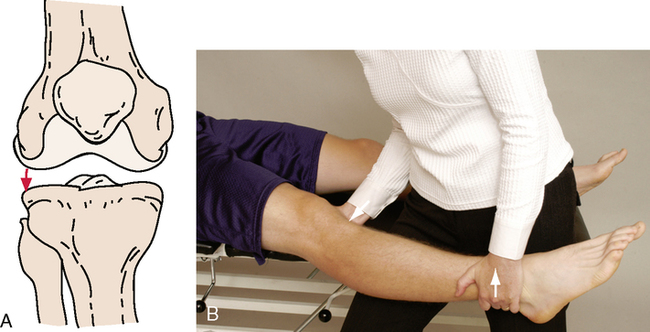

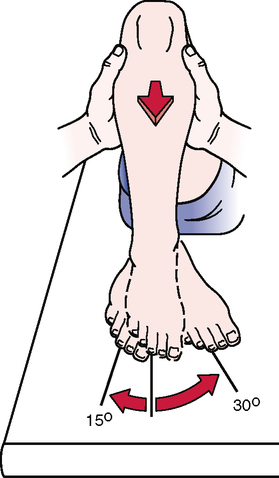

SPECIAL TESTS FOR ONE-PLANE ANTERIOR INSTABILITY

Relevant Special Tests