Kidneys, Ureters, and Urinary Bladder

The Kidney and Systemic Diseases

Many primary systemic diseases affect the kidney, including diabetes mellitus (DM), essential hypertension, various renovascular diseases, and several toxic and metabolic disorders. Progressive renal disease (diabetic nephrosclerosis, Kimmelstiel-Wilson disease) is a common complication of DM (see chapter 12) and is responsible for renal failure in 30% to 40% of patients with insulin-dependent DM and 20% of those with non–insulin-dependent DM. Benign and malignant nephrosclerosis are the renal manifestations of essential hypertension and must be distinguished from renovascular hypertension, the consequence of renal artery stenosis. Hypertensive vascular diseases affect approximately 20% of the population and, with the complications of myocardial infarction, renal failure, and stroke, constitute a major health hazard. (The cause and pathogenesis of hypertension are discussed in chapter 2.) Systemic vasculitis syndromes frequently affect renal vessels or glomeruli or both (Table 6-1). Toxic nephropathy encompasses a large variety of diseases of different origins causing pathologic changes including cortical necrosis, tubular necrosis, focal hemorrhage, interstitial nephritis, and papillary necrosis. Causative toxins may be exogenous (e.g., drugs, plant toxins, allergens) or endogenic (e.g., toxemia of pregnancy), and the pathogenesis may include immune mechanisms (e.g., Shwartzman-Sanarelli syndrome). Metabolic disturbances such as amyloidosis and hypokalemic and calcium nephropathy also are associated with renal pathology.

TABLE 6-1

SUMMARY OF SYSTEMIC VASCULITIS SYNDROMES (PRIMARY AND SECONDARY)

| Affected Vessel | Entity | Clinical Features |

| Small | Wegener disease Microscopic polyangiitis Henoch-Schönlein purpura Leukocytoclastic vasculitis Postinfectious vasculitis (eg, viral) |

Microhematuria, purpura, hemoptyses, perimyocarditis, episcleritis, vertigo, polyneuritis, melena |

| Medium | Pan(poly)arteritis nodosa Churg-Strauss disease Lupus erythematosus Rheumatoid arthritis Progressive systemic sclerosis |

Infarction in various organs including kidneys, hemorrhage from ruptured microaneurysms, hypertension, renal failure |

| Large | Giant cell arteritis Takayasu arteritis |

Arterial stenoses, phlebothromboses, aortic arch syndrome, subclavian steal syndrome |

Diseases of the Urinary System

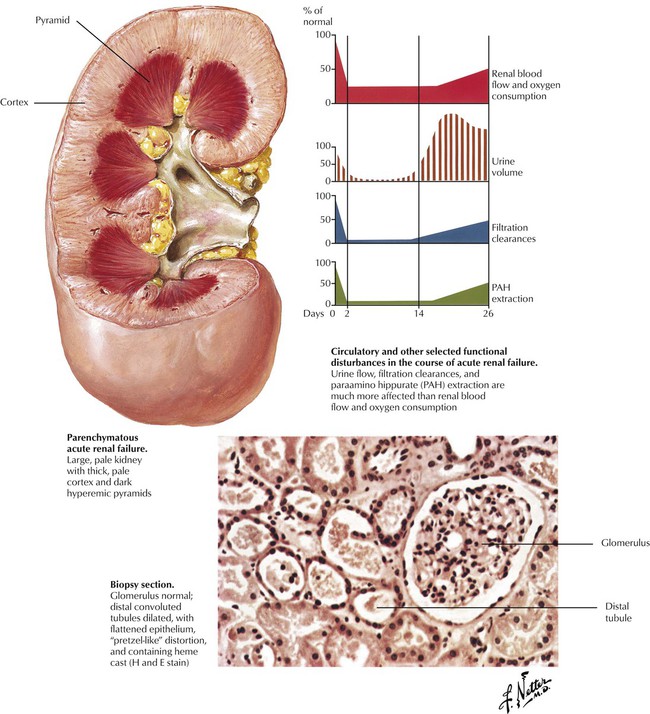

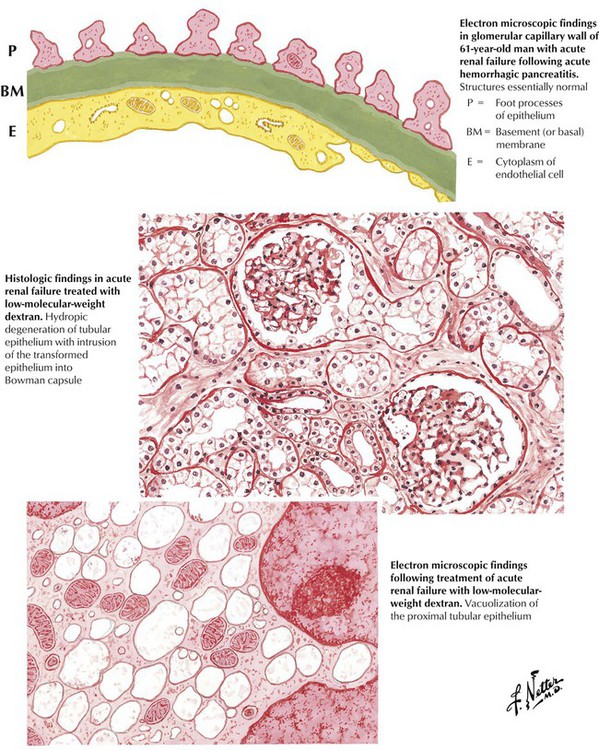

Acute renal failure is a sudden reduction in renal function with accompanying oliguria or anuria and potentially fatal outcome. There are 3 types of ARF: prerenal, renal (parenchymal), and postrenal. In prerenal failure, which is reversible, renal function is reduced by factors extrinsic to the kidney, such as hypotension, salt depletion, dehydration, or an obstruction in the urinary tract. Renal (parenchymal) failure follows malfunction of the nephrons in a wide variety of diseases, including acute glomerulonephritis, acute pyelonephritis, toxic nephropathy, and severe circulatory impairments, with the latter resulting in acute tubulointerstitial nephropathy or “shock kidney.” The pathophysiologic derangements in ARF are complex but include reduced and maldistributed cortical blood flow with resulting local ischemia while total blood flow is partially preserved. Postrenal causes of ARF are various forms of urinary tract obstruction.

The kidneys of patients with acute renal failure (ARF) are large and pale, with a pale cortex and a dark, hyperemic medulla. Histologically, the hallmark of the condition is multifocal dilation with epithelial flattening of the distal convoluted tubules and, to some extent, the proximal convoluted tubules. The glomeruli are normal. Tubular epithelial cells exhibit degenerative and hydropic changes. Interstitial edema and focal collections of lymphocytes may be present. Electron microscopy confirms the normal structure of the glomeruli and reveals subcellular degenerative changes of organelles. There is a progressive decrease in urine output and a progressive increase in azotemia, metabolic acidosis, and serum potassium levels. Renal function returns if the underlying disease process is contained and the renal-induced metabolic and electrolyte abnormalities are treated successfully.

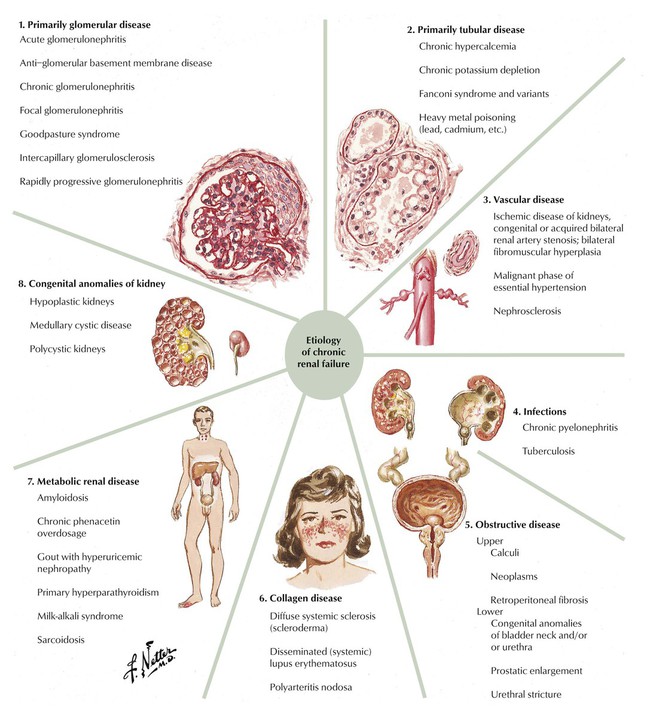

Chronic renal failure (CRF) is a marked impairment in renal homeostatic function coupled with abnormalities in composition of body fluids. The most common causes of CRF are various types of glomerulonephritis and other nephritides. The functional and structural consequences of ischemia—obstruction with increased intra-pelvic pressure, infection with microorganisms, or deposition of antigen-antibody-complement complexes—may also result in CRF. Renal insufficiency is characterized by impaired renal adaptive function without major alterations in body fluid composition. Further loss in function results in CRF and culminates in uremia. Changes induced by CRF include secondary hyperparathyroidism and metabolic bone disease. In humans, the common structural basis for renal failure is thought to be a progressive reduction in the number of functioning nephrons, while the remaining nephrons develop hypertrophy and increased work per nephron, until these nephrons also are lost.

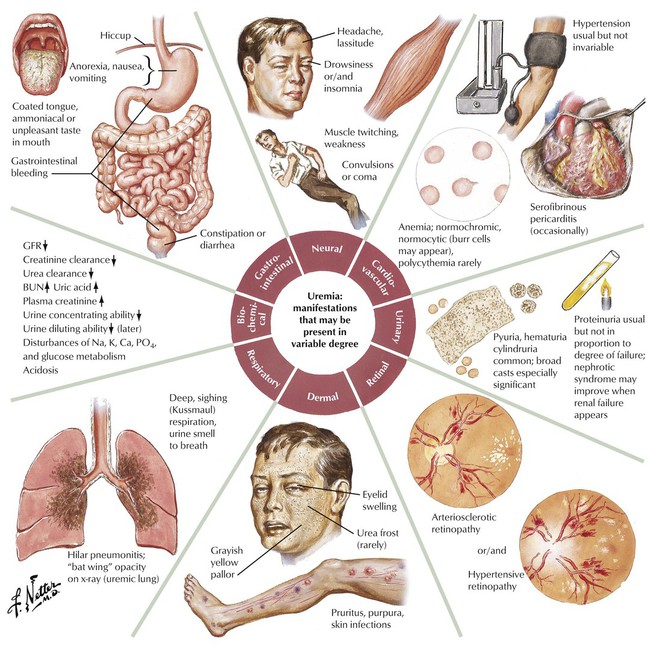

Uremia is characterized by multiple clinical and laboratory findings resulting from severe renal failure. Azotemia, a hallmark of renal failure, which is characterized by increased concentration of nonprotein nitrogenous compounds in blood, is measured with the blood urea nitrogen (BUN) test. Reduction in glomerular filtration can be measured by the diminution of creatine clearance and resulting increase of creatinine in the blood.

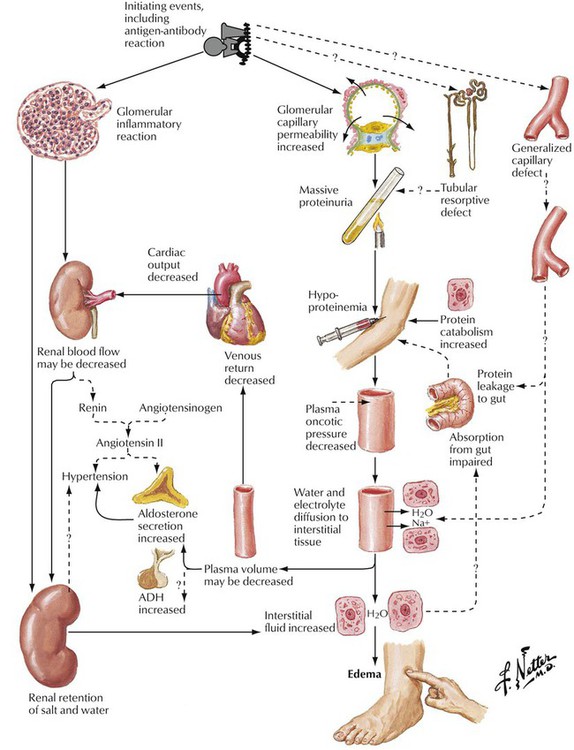

Nephrotic syndrome may be induced by noninflammatory or inflammatory (glomerulonephritic) conditions. The resultant damage, which may be subtle, produces increased permeability of the glomerular capillaries leading to proteinuria. Clinically, nephrotic syndrome is characterized by proteinuria in excess of 3.5 g/d/1.73 m2 body surface area, edema, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperlipidemia. Prolonged massive proteinuria and resultant hypoproteinemia are the common denominators for all consequent metabolic and nutritional defects. Glomerular inflammation also may lead to a decrease in renal blood flow, which may activate the renin-angiotensin system, increasing production of angiotensin II and causing hypertension.

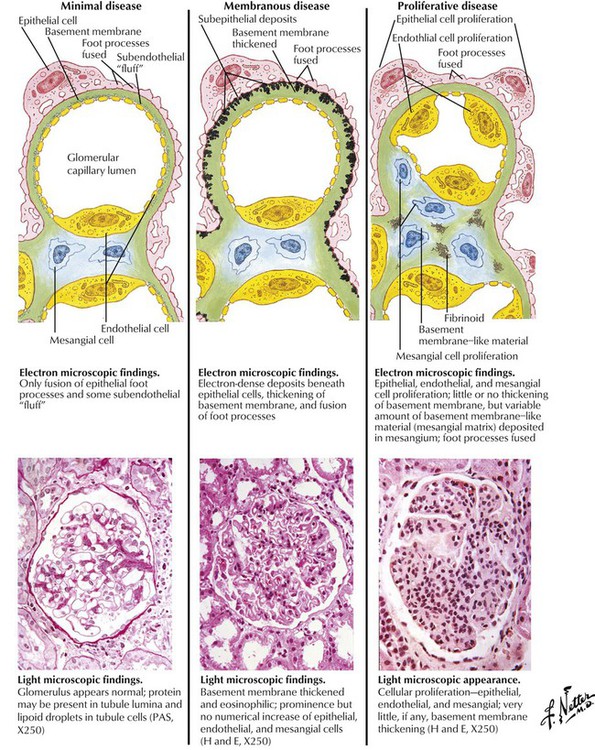

A spectrum of glomerular lesions can produce nephrotic syndrome. Minimal change disease (lipoid nephrosis) shows little or no change by light microscopy. Fused epithelial foot processes and occasional immunoglobulin (Ig) M deposits are seen by electron microscopy. If the disease is complicated by focal and segmental sclerosis, fused epithelial foot processes, capillary collapse, or mesangial expansion with γ-globulin deposits, response to immunosuppressive therapy deteriorates. Membranous nephropathy is characterized by thickened capillary walls, spikes in the basement membrane due to antigen-antibody complexes beneath the epithelial cells (membranous disease), and diffuse granular deposits of IgG and C3 (complement). Mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis shows thickening of glomerular capillary walls complicated by mesangial proliferation and sclerosis with subendothelial deposits of C3 and IgG in a lumpy, nonlinear pattern. Focal segmental inflammatory necrosis and crescent formation signals a poor response to immunosuppressive therapy.

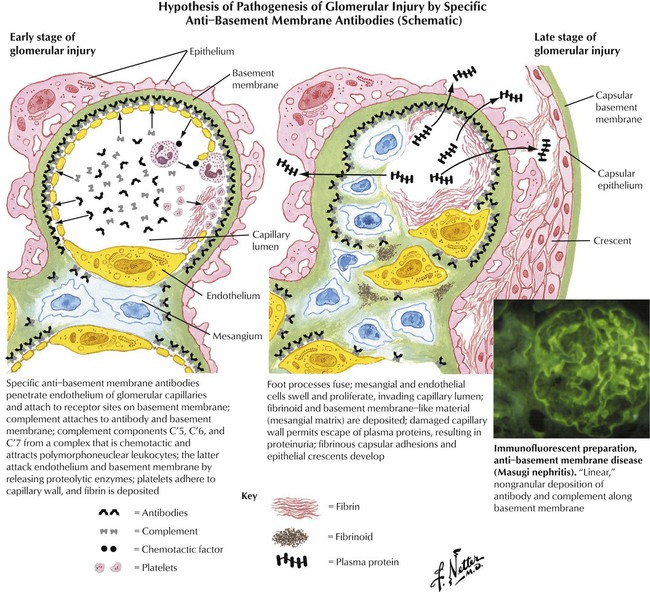

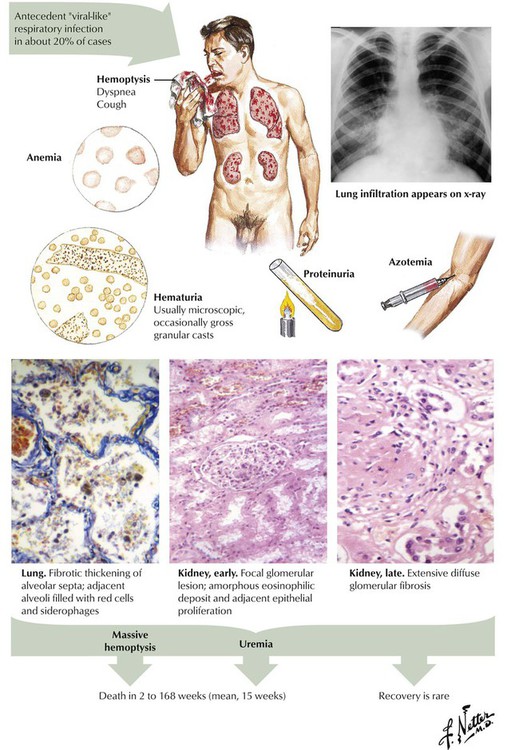

In anti–glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease, the antibody is directed against the GBM, the antigen being a normal component of the glomerulus. Anti-GBM disease, whether produced by heterologous antibodies or autoantibodies, has the following features: (1) it is produced by circulating antibodies; (2) the antibodies (γ globulins) and complement are readily detected by immunofluorescence with a distribution along the basement membrane of every glomerulus in a highly distinctive, continuous, linear pattern; and (3) electron microscopy reveals inconspicuous deposits along the endothelial side of the basement membrane. Leukocytes recruited by locally produced chemotactic factors contribute to the glomerular damage. Forms of anti-GBM disease in humans include rapidly progressive, subacute glomerulonephritis and Goodpasture syndrome, which is characterized by lung hemorrhage and severe and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

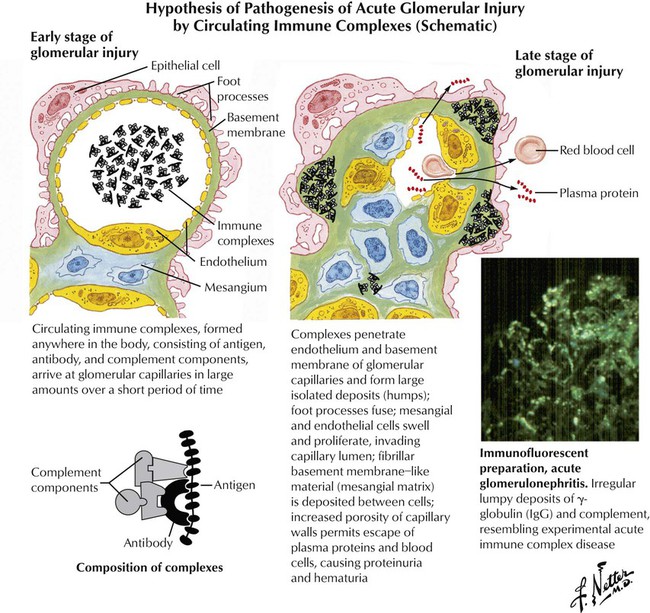

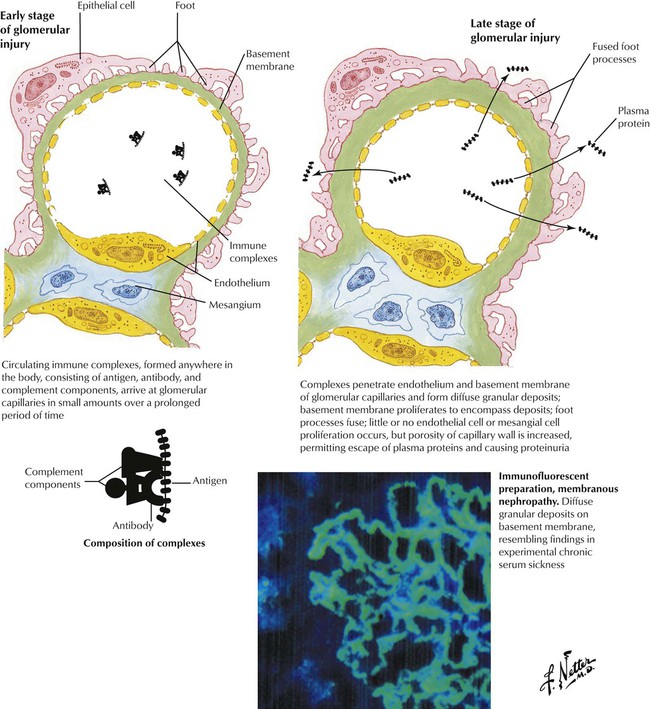

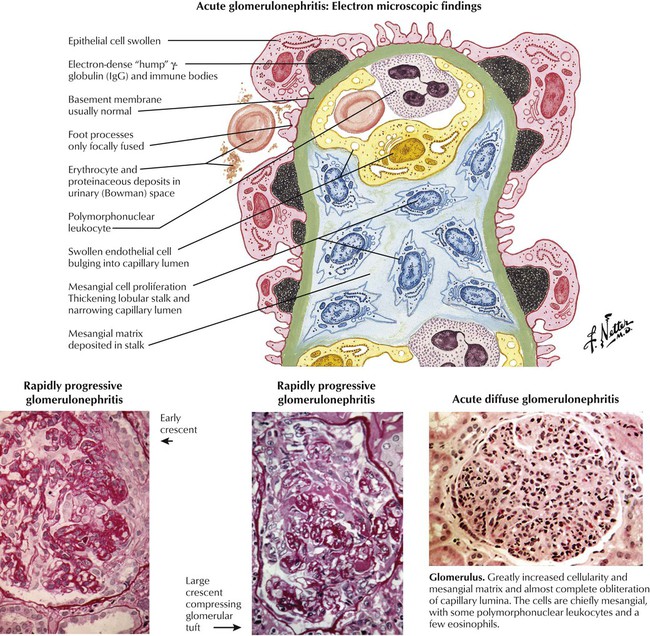

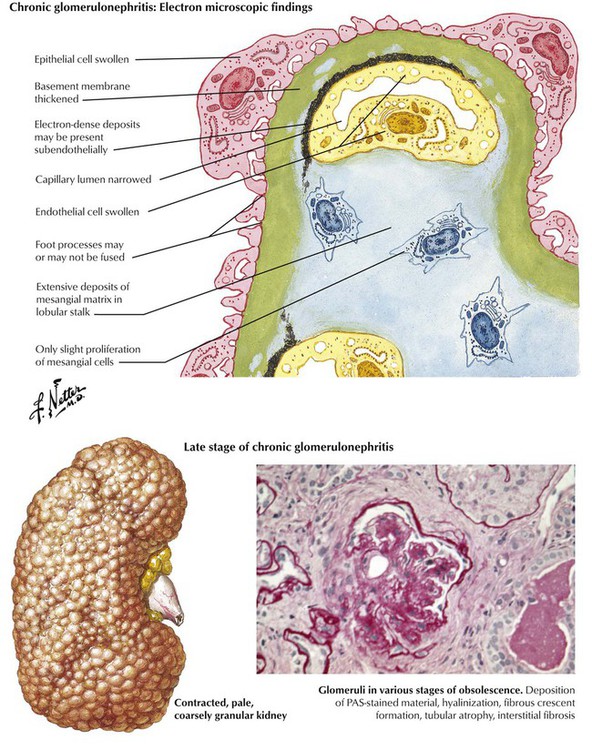

Acute glomerular injury results when large amounts of immune complexes are delivered to the glomerular capillaries over a short period of time; examples are poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and the glomerulonephritis associated with subacute bacterial endocarditis. The immune complexes form large deposits on the epithelial side of the basement membranes, which are detected by immunofluorescence as irregular lumpy deposits and by electron microscopy as subepithelial humps in the basement membranes. The immune complexes stimulate an inflammatory response that leads to acute glomerulonephritis. Chronic glomerular injury also results when small amounts of immune complexes are delivered to the glomerular capillaries over a prolonged period, as seen in systemic lupus erythematosus. Electron microscopy and immunofluorescence show extensive deposits of immune complexes along the epithelial side of the basement membrane. The glomerular injury may progress to include proliferative and sclerosing changes.

The kidneys in acute diffuse (poststreptococcal) glomerulonephritis show enlargement and pallor. Abnormally large and cellular glomeruli are seen microscopically; the capillary walls are swollen, and the lumens are narrowed. The hypercellularity is caused by proliferation of mesangial cells with associated increased mesangial matrix. A variable amount of infiltration by polymorphonuclear leukocytes is seen early in the disease. Other changes include casts and erythrocytes in the tubules and interstitial edema and focal inflammation. Electron microscopy reveals swelling of epithelial and endothelial cells and increased numbers of mesangial cells. The presence of semicircular or triangular “humps” (protein deposits) between the basement membrane and epithelial cells are considered to be diagnostic. Rapidly progressive (extracapillary) glomerulonephritis is characterized by the presence of many large cellular crescents consisting of proliferated epithelial cells of Bowman capsules, macrophages, and matrix.

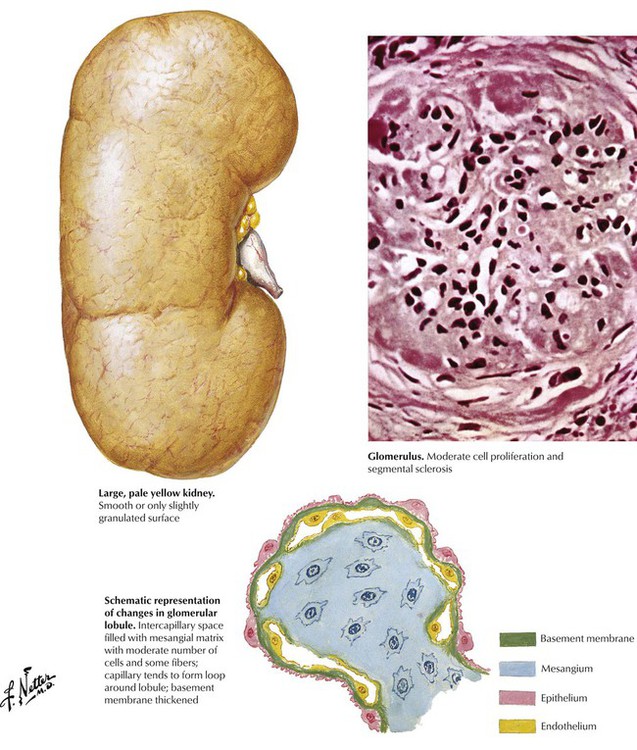

Chronic glomerulonephritis is characterized pathologically by sclerosis of many glomeruli and clinically by manifestations of renal insufficiency. The disease progresses because of inflammation leading to sclerosis of glomeruli and scarring. The kidney may be normal or slightly increased or decreased in size and is often pale yellow with smooth or slightly granular surfaces. On cut section, the cortex is often pale and swollen as a result of lipid in the tubules and interstitial edema. In proliferative and sclerosing glomerulonephritis, the glomeruli typically exhibit cellular proliferation and deposition of intercellular material with an approximate balance between proliferation of cells and sclerosis. In contrast, in membranous glomerulonephritis, cell proliferation and sclerosis are absent, and the histologic changes are limited to the capillary walls, at least in the early stages.

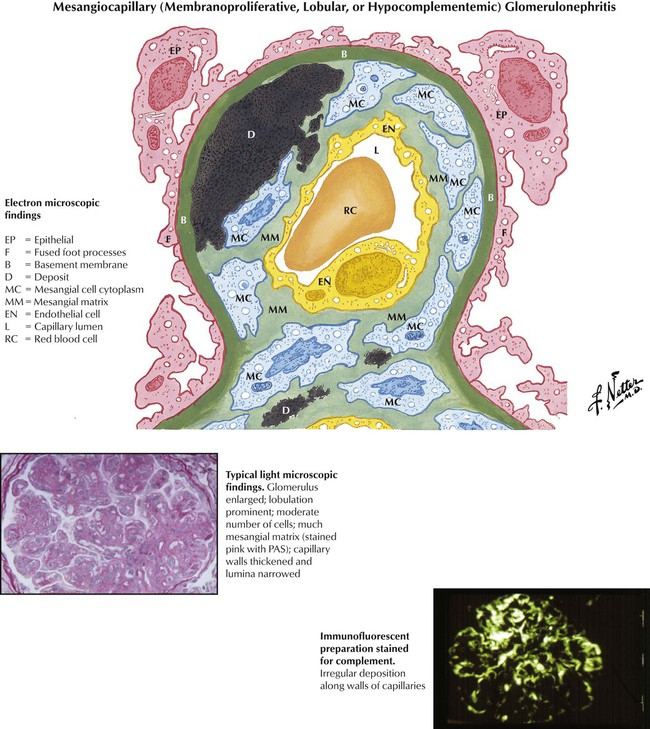

Mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (membranoproliferative, lobular, or hypocomplementemic glomerulonephritis) occurs most often in children and young adults. Patients present with components of the nephrotic syndrome and, usually, depression of serum complement. Typically, the disease progresses slowly. Histologically, the glomeruli are enlarged and moderately cellular, and the lobular centers are expanded as a result of proliferation of the mesangial cells and matrix. Ingrowth of the mesangium into the capillary wall causes capillary wall thickening, separates the endothelium from the basement membrane, and narrows the lumen. Immunofluorescence reveals deposits of complement (C3) and small amounts of γ globulin (IgG, IgM) within the mesangial matrix.

Membranous glomerulonephritis is common in adults but not in children. Characteristic changes in the capillary basement membranes are seen by electron and light microscopy (silver stains). Small, dense protein deposits that contain γ globulin (IgG) and complement are located between the basement membrane and the overlying, fused epithelial cell foot processes (see Fig. 6-6). The deposits are interrupted by focal thickening or by projections (spikes) of the basement membrane. Late chronic glomerulonephritis represents an end-stage common pathway of many glomerular diseases. Pathologically, it is characterized by the predominance of scarring and atrophy of both glomeruli and tubules with secondary arteriolosclerosis.

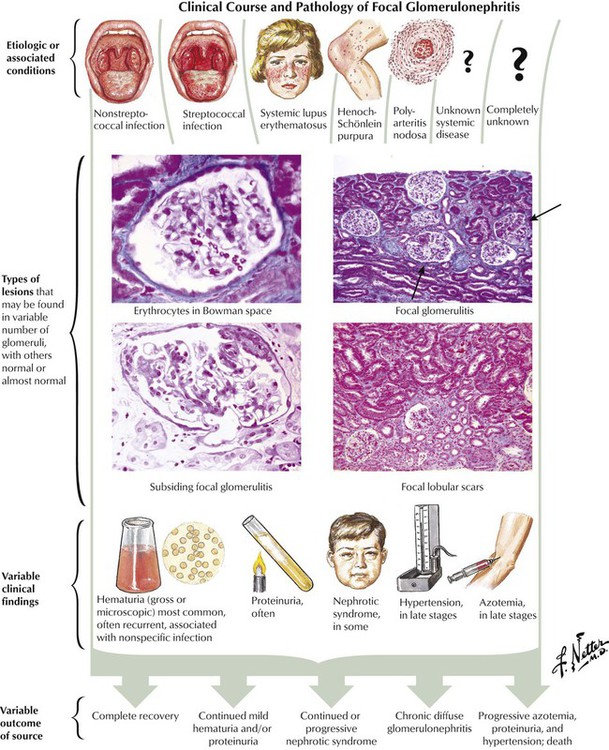

Focal segmental glomerulonephritis refers to disease processes in which some but not all glomeruli are involved, portions but not the entirety of each glomerulus are involved, or both. Etiologic or associated conditions include streptococcal and nonstreptococcal infections; autoimmune and immunologically mediated diseases, including systemic lupus erythematous and Henoch-Schönlein purpura; and various vasculitides, including polyarteritis nodosa. A variety of pathologic lesions ranging from mild or moderate to severe focal glomerular damage may be found. Clinical findings may include hematoma, azotemia, hypertension, and nephrotic syndrome. The clinical course and outcome range from self-limited disease to death.

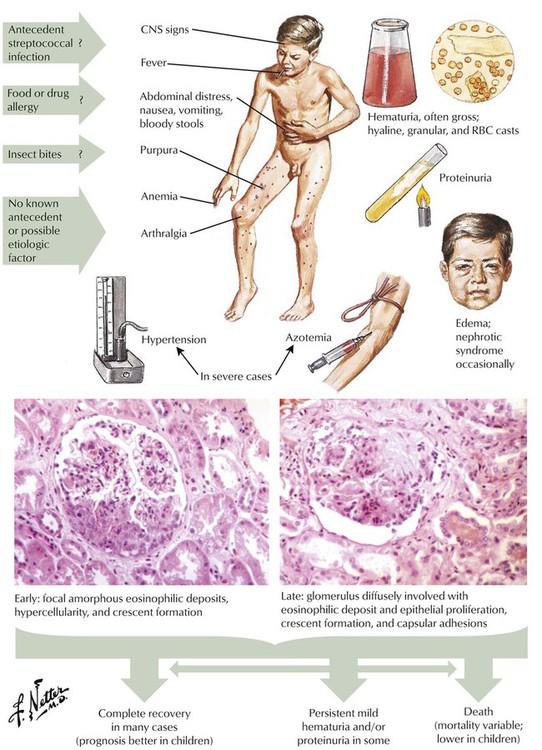

Anaphylactoid purpura (Henoch-Schönlein disease), a hypersensitivity disorder with renal involvement, usually affects children. The disorder closely resembles serum sickness in humans and experimental animals. Multiple allergens may be involved. Skin lesions include urticaria, maculopapular rash, petechiae, and purpura. Joints may become inflamed, painful, and swollen. Other features may include central neurologic signs, gastrointestinal involvement, and anemia. Renal manifestations are dominated by hematuria and nephrotic syndrome, which in severe cases may be accompanied by hypertension and azotemia. Renal biopsies show variable involvement of most of the glomeruli, with focal changes consisting of proliferation of endothelial and mesangial cells and accumulation of periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reaction–positive matrix material.

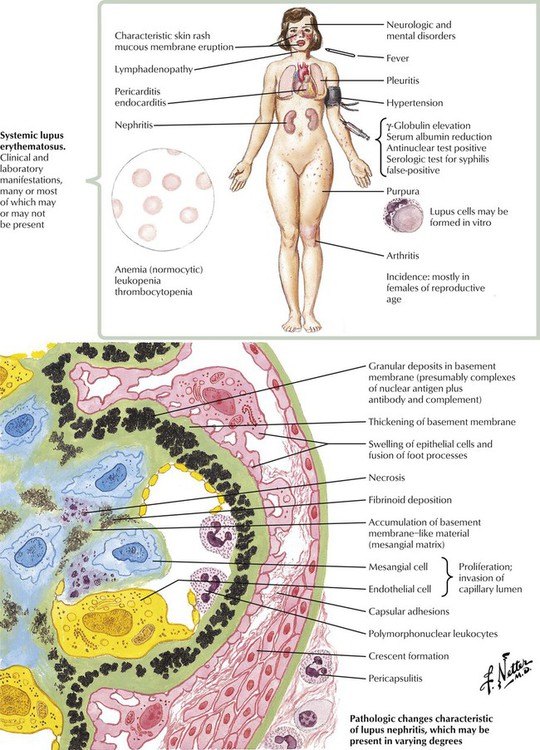

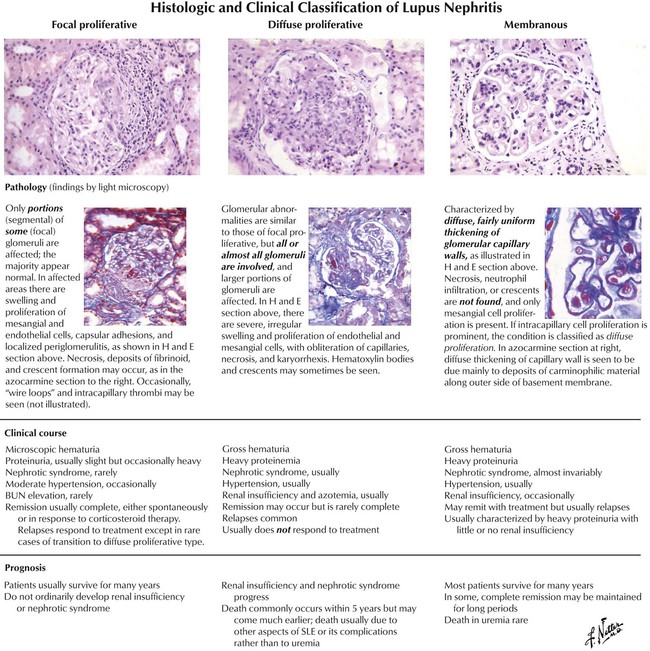

Systemic lupus erythematosus, an autoimmune disease that occurs predominantly in young women, involves many tissues and organs. Important renal abnormalities involving the glomeruli include swelling and proliferation of endothelial and mesangial cells, fibrinoid necrosis, thrombi, neutrophil infiltration, crescent formation, increased mesangial matrix, and thickening. Deposits of antigen-antibody complexes in the basement membrane often appear as “wire-loop” lesions. Focal proliferative lupus nephritis (class III) is characterized by focal involvement of some of the glomeruli, swelling and proliferation of endothelial and mesangial cells, neutrophil accumulation, and necrosis.Diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis (class IV) is characterized by involvement of most glomeruli coupled with more prominent accumulation of basement membrane material and more severe and widespread interstitial inflammation. Diffuse membranous lupus nephritis is characterized by diffuse abnormalities of the basement membranes resembling those of idiopathic membranous nephropathy.

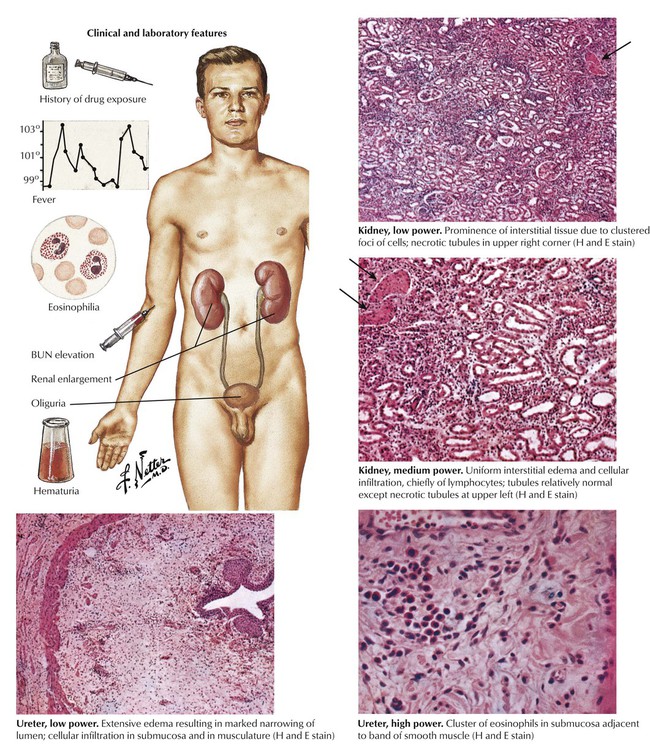

Acute diffuse interstitial nephritis, although uncommon, is an important cause of acute oliguric renal failure. It usually occurs as a manifestation of a hypersensitivity reaction to sulfonamides, penicillins, or other drugs (drug reaction). The characteristic features are fever, rash, eosinophilia, hematuria, oliguria, and azotemia. The kidneys are enlarged and may be 3 times their normal weight. Microscopy reveals pronounced edema and cellular infiltration by lymphocytes, eosinophils, and, occasionally, plasma cells. Parenchymal damage is minimal and is usually limited to focal tubular necrosis.

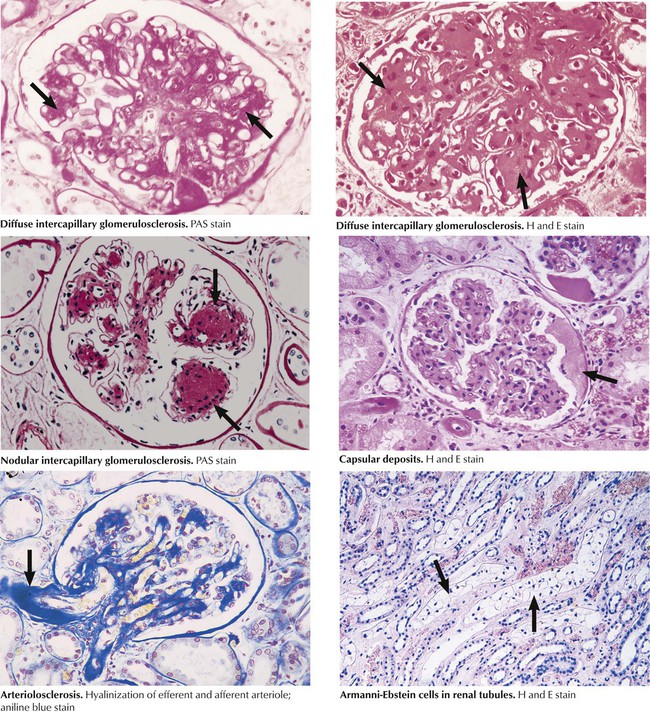

In diabetic glomerulosclerosis, a characteristic lesion occurs in diffuse and nodular (Kimmelstiel-Wilson) forms when increased amounts of PAS basement membrane material accumulate in the mesangium (intercapillary glomerulosclerosis) and the capillary walls. The pathogenesis of the glomerulopathy seems to involve accelerated degeneration and turnover of connective tissue cells coupled with abnormal glycosylation of matrix proteins. The capillary walls, although thickened, become porous, giving rise to nephrotic syndrome. Similar degeneration and accumulation of glycosylated proteins occurs in the walls of the microvasculature, giving rise to hyaline thickening (arteriolosclerosis) of both the afferent and efferent glomerular arterioles. Other lesions include hyaline, lipoproteinaceous deposits in the parietal layer of Bowman capsules, lipohyaline deposits in glomerular capillaries, thickening of the tubular basement membranes, and glycogen-filled epithelial cells in the distal, straight portion of the proximal tubule (the Armanni-Ebstein lesion).

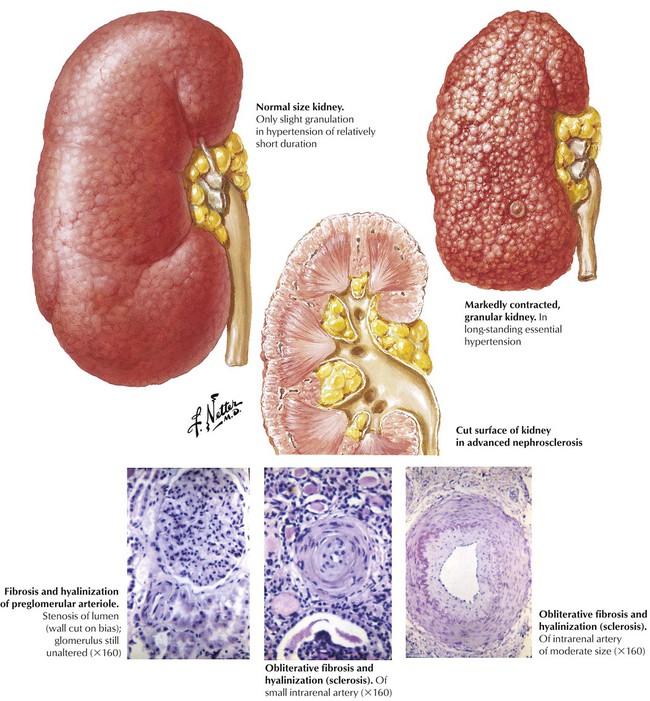

Benign essential hypertension is a poorly defined condition of multifaceted origin characterized by persistent, moderate increase of systemic blood pressure. Over time, progressive damage occurs to the resistance vessels, leading to hyaline arteriolosclerosis in the kidneys and other organs. The small and medium intrarenal arteries become involved, which leads to fibrosis, hyalinization (sclerosis), and narrowing of the lumen. The hyaline material is composed of degenerated vascular cells and plasma proteins that have leaked into the vessel. Fibrosis results from active laying down of collagen by vascular cells. The narrowing of the arterioles and small arteries results in multifocal ischemia and small scars throughout the renal cortex giving rise to a thinned cortex and a finely granular surface. These changes lead to progressive renal insufficiency.

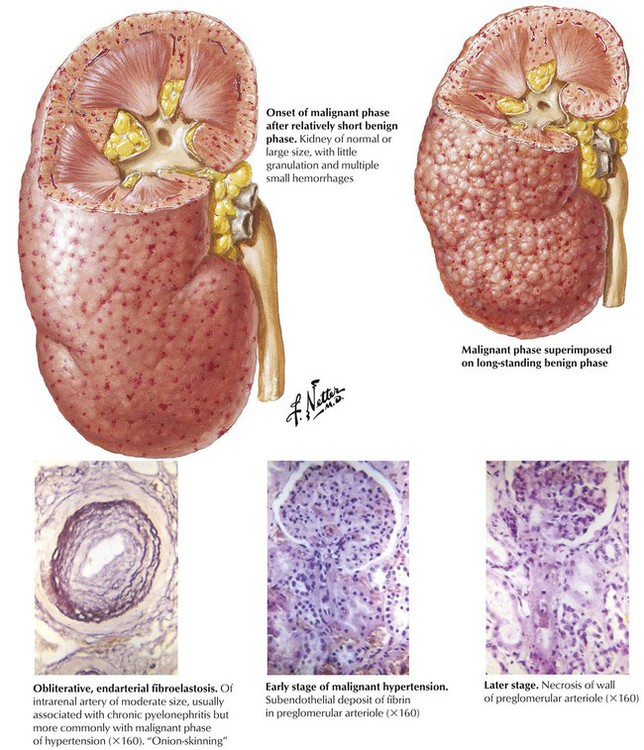

Malignant hypertension is closely associated with renal ischemia due to parenchymal or renovascular abnormalities or to rapid progression of renal changes in essential hypertension. The kidney may be of normal size with minimal granularity or shrunken and scarred, depending on the extent and duration of preexistent moderate hypertension. The characteristic gross feature of malignant hypertension is the presence of multiple petechial hemorrhages, reflective of multifocal severe ischemia, which produce the “flea-bitten” kidney. Hyperplastic arteriolosclerosis, the characteristic microscopic lesion in widespread obliterative fibroelastosis of arterioles and small arteries, is accompanied by glomerular and interstitial hemorrhage and fibrin deposition. Severe malignant hypertension produces fibrinoid necrosis of the afferent glomerular arterioles.

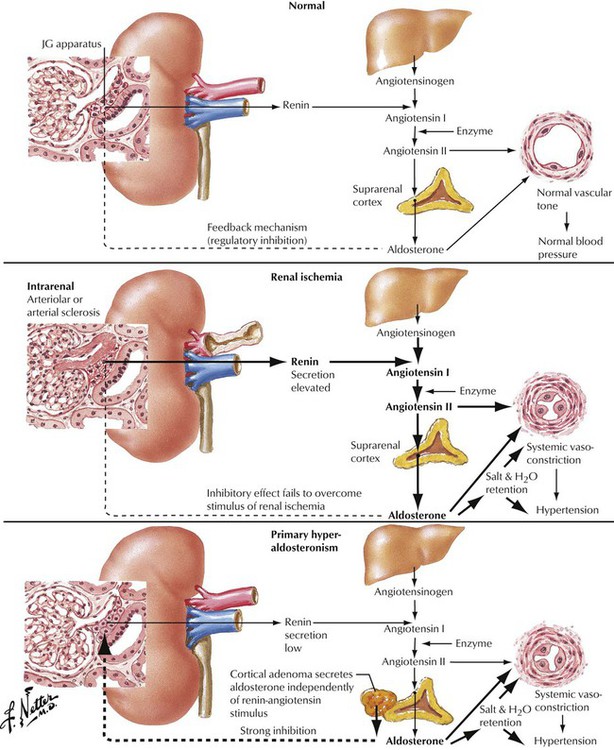

Various stenosing or obstructing lesions of the extrarenal vasculature, especially stenosis of the main renal artery, often result in hypertension. Such lesions include arteriosclerotic plaques, various forms of fibromuscular dysplasia, obstruction, and trauma. An appropriate evaluation is needed to determine whether the lesion is unilateral and whether the hypertension is likely to be relieved by surgery. The renin-angiotensin system has an important role in both extrarenal renovascular hypertension and hypertension due to intrarenal disease. Renal ischemia leads to increased renin excretion, which is followed by production of increased levels of angiotensin I and II and increased release of aldosterone. In primary hyperaldosteronemia, aldosterone is increased, and levels of renin and angiotensin are low.

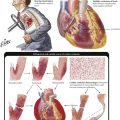

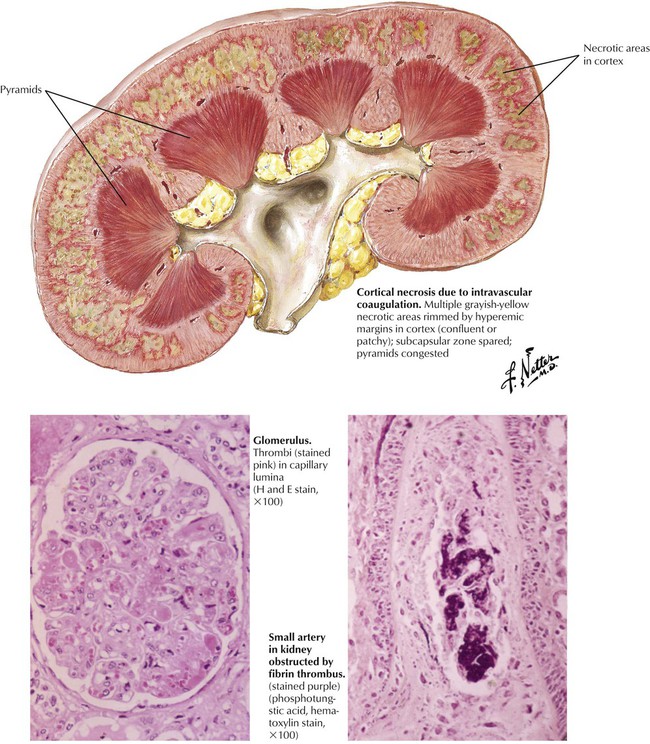

Intravascular coagulation and thrombotic microangiopathy (hemolytic-uremic syndrome [HUS]) is characterized by hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, intravascular coagulation, hypertension, and renal failure. HUS occurs as an idiopathic disease, usually in infants and young children, or during the course of systemic disease (e.g., malignant hypertension, eclampsia, and disseminated carcinomatosis). The histologic picture is dominated by fibrin-platelet thrombi in many glomerular capillaries and in small arteries, which sometimes exhibit fibrinoid necrosis. The accumulation of pale, finely granular or fibrillar material between the endothelium and the capillary basement membranes of the glomeruli is an important feature of HUS. Immunofluorescence shows that the deposits contain fibrinogen and globulin. The affected capillary walls are thick, and the lumens are narrow. The combination of arteriolar thrombosis and capillary wall thickening constitutes the entity of thrombotic microangiopathy.

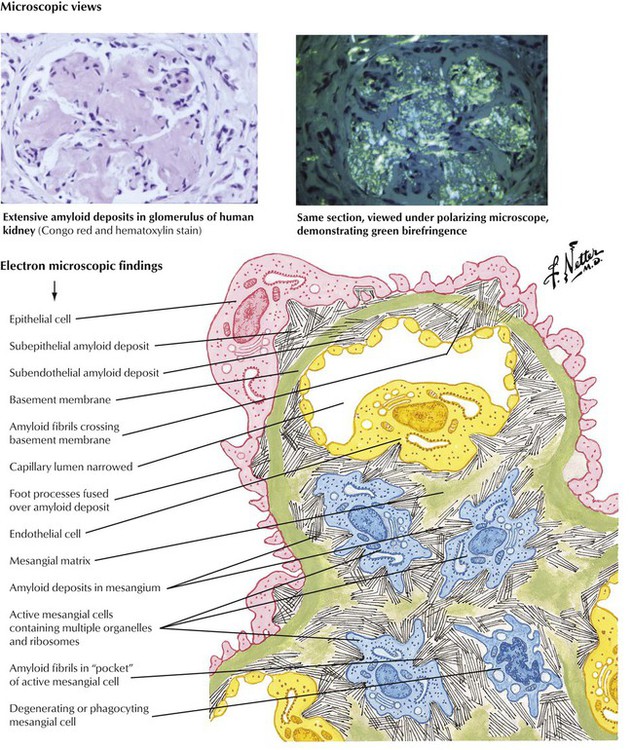

The kidneys are frequently involved in various forms of amyloidosis. Marked proteinuria is the usual mode of presentation, and overt nephrotic syndrome occurs in most cases. Homogeneous hyaline deposits of amyloid involve the arterioles and the glomeruli. When examined under polarized light, Congo red–stained sections show typical apple-green birefringence as a result of the β-pleated sheet configuration of the amyloid protein. Electron microscopy reveals that amyloid deposits are composed of masses of nonbranching fibrils of 7.5 to 10 nm in diameter, which are much smaller than collagen fibrils found in the foci of ordinary fibrosis.

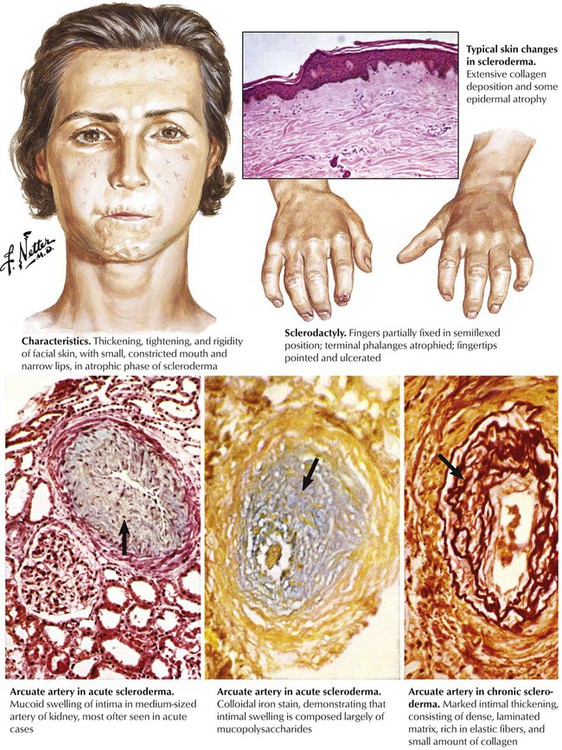

Progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) is a systemic disease characterized by the accumulation of excess collagen and the presence of vascular lesions with little inflammation. The classic form exhibits widespread involvement of skin and internal organs. Vascular lesions are particularly striking in the kidneys. Medium-sized renal arteries exhibit variable combinations of mucoid swelling of the intima and fibroelastic intimal proliferation, similar to the onion-skinning seen in malignant hypertension. When renal involvement becomes clinically apparent, it progresses rapidly, and malignant hypertension, retinopathy, encephalopathy, and renal failure ensue. Renal involvement in rheumatoid arthritis is less common and usually less severe than in other autoimmune diseases. The basic lesion, a multifocal vasculitis, involves small arteries and veins.

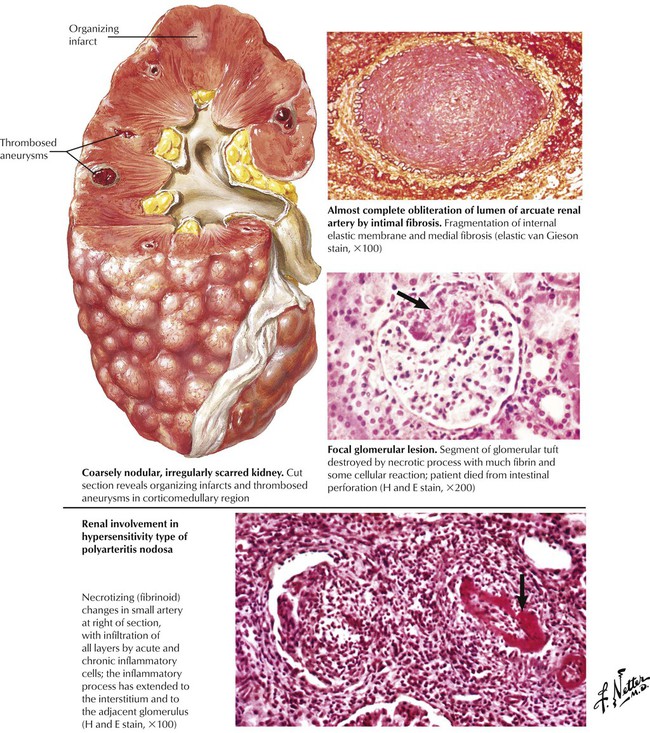

Polyarteritis nodosa refers to a constellation of inflammatory and necrotizing disease processes that involve medium and small arteries, most commonly in the kidneys, the gastrointestinal tract, and the heart. Classical polyarteritis nodosa produces multifocal involvement of medium or larger arteries. The kidneys may be coarsely nodular and irregularly scarred as a result of regional areas of ischemia and infarction of various ages. Acute lesions are characterized by fibrinoid necrosis of the arterial wall with inflammatory cellular infiltration by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and plasma cells in the adventitia extending into the media. Healing lesions exhibit medial fibrosis, focal destruction of the internal elastic lamella, and intimal fibrosis. The hypersensitivity type of polyarteritis nodosa is dominated by fibrinoid necrosis and inflammation of small arteries. In the kidney, Wegener granulomatosis shows segmental and focal necrotizing glomerular lesions and a granulomatous and necrotizing arteriolitis.

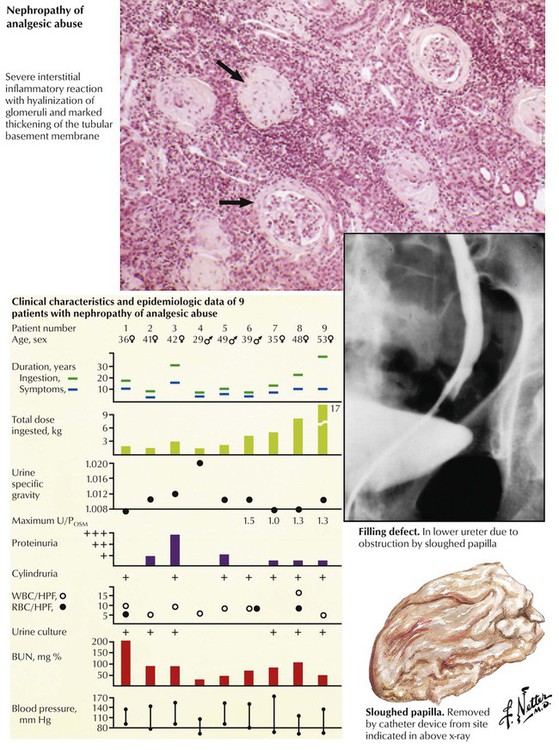

Toxic nephropathy encompasses any adverse functional or structural change in the kidney produced by a chemical or biological product. The renal tubules are a frequent target of injury. Nephrotoxins include heavy metals (mercury, lead), organic chemicals (carbon tetrachloride, ethylene glycol), drugs (many antibiotics, analgesics), pesticides (e.g., chlorinated hydrocarbons), physical agents (radiation), and products of metabolic disturbances, including hyperuricemia, hypercalcemia, and hypokalemia. Nephrotoxins may act directly on the nephrons or may produce hypersensitivity reactions, which result in vasculitis, nephritis, or nephrotic syndrome. With the toxic nephropathy resulting from excessive intake of mixed analgesic tablets, especially those containing phenacetin, the pathologic process is one of chronic interstitial nephritis with inflammatory cellular infiltration and fibrosis and a tendency for papillary necrosis.

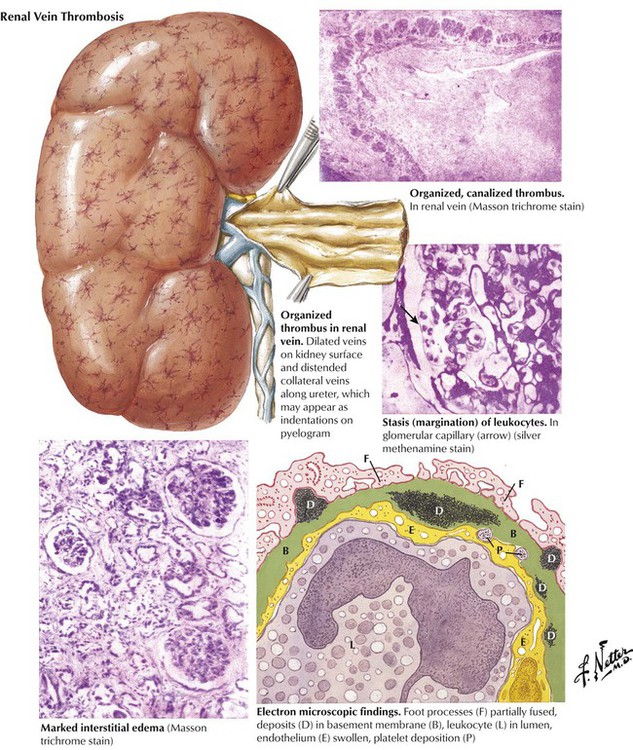

Renal vein thrombosis is an uncommon cause of nephrotic syndrome. It may occur as a complication of previously existing renal disease or as a primary disease after trauma, particularly in individuals predisposed to venous thrombosis, or as a result of compression of the renal vein by tumors or adhesions. In infants and children, severe dehydration may lead to acute renal vein thrombosis producing renal cortical necrosis and severe renal insufficiency. In adults, the typical presentation is nephrotic syndrome with severe proteinuria. The kidneys become extremely enlarged as a result of interstitial edema, and their surfaces may exhibit small, dilated veins. By electron microscopy, the glomeruli show fusion of epithelial foot processes and the presence of dense osmiophilic deposits on both sides of and sometimes within the basement membrane. These deposits have been shown to consist of IgG, IgM, complement, and fibrin-fibrinogen.

Lung purpura with nephritis (Goodpasture syndrome) is an acute condition involving the lungs and the kidneys. The characteristic feature is profound hemoptysis, which may lead to severe anemia and very low serum iron levels. Chest radiography typically shows cardiomegaly and striking pulmonary opacities. The pathologic counterpart is a hemorrhagic alveolitis. Kidney involvement, which may develop simultaneously with or subsequent to the pulmonary lesion, manifests clinically by gross or microscopic albuminuria and pathologically by necrotic and proliferative lesions. Hypertension generally does not develop.

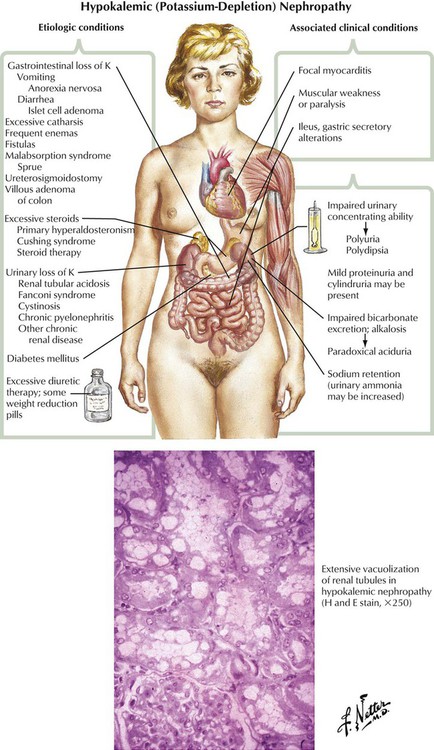

Hypokalemic nephropathy may result from excessive fluid loss through the gastrointestinal tract, excess fluid loss in the urine, excessive sterol levels, or miscellaneous conditions. Renal dysfunction includes impaired urinary concentrating ability, impaired bicarbonate excretion, alkalosis with paradoxical aciduria, and sodium retention. The characteristic histologic finding is marked vacuolization of renal tubular epithelium, which is more marked in the proximal convoluted tubules than in the distal. Clinical manifestations include focal myocarditis, muscle weakness or paralysis, and ileus.

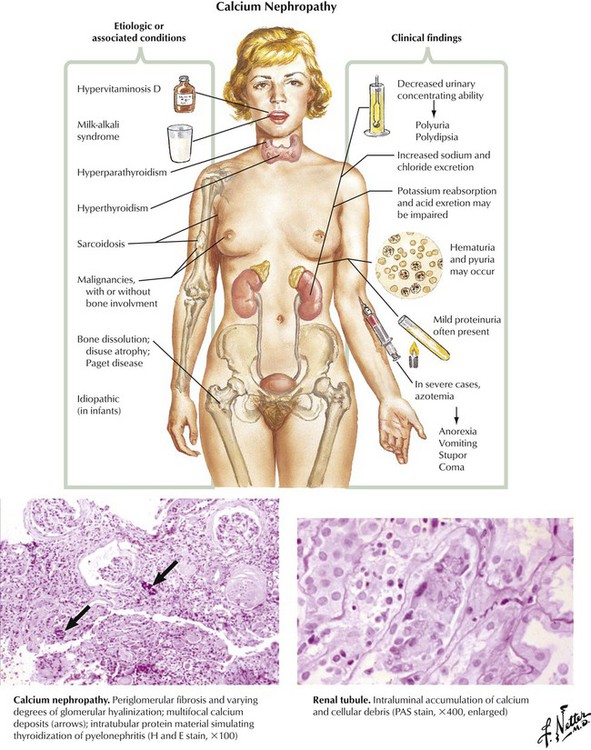

A variety of metabolic states and systemic diseases may result in an excess calcium load to the kidneys. Clinical findings include decreased urinary concentrating ability; increased sodium and chloride excretion; hematuria; mild proteinuria; and, in severe cases, azotemia, anorexia, stupor, and coma. Pathologically, multifocal calcification of interstitial tissue, distal convoluted tubules, and collecting ducts may be seen. Glomeruli frequently show partial or complete hyalinization, and chronic inflammatory changes are frequently present.

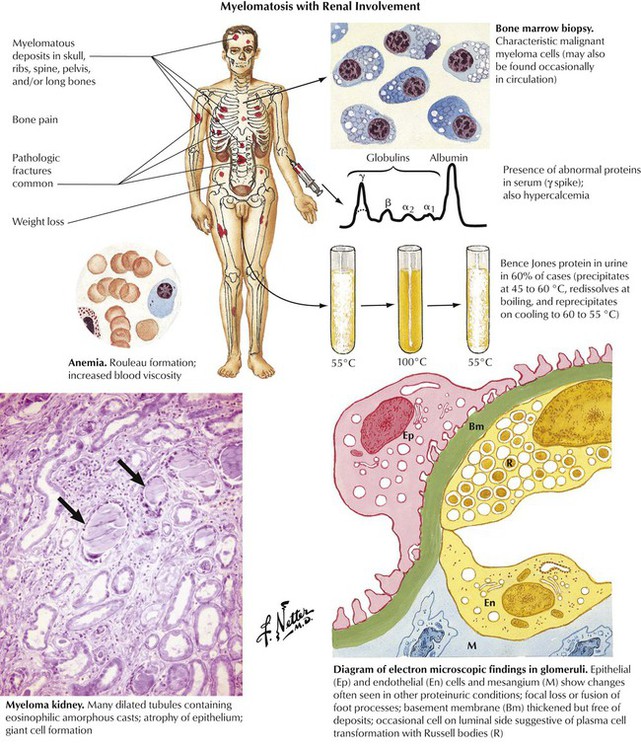

Multiple myeloma is a part of the clinical spectrum of paraproteinemias in which neoplastic plasma cells infiltrate bone, lymph nodes, and various soft tissues and elaborate abnormal serum proteins. These proteins typically produce a monoclonal γ-globulin spike on serum electrophoresis. Approximately 15% of individuals with multiple myeloma also have amyloidosis. In at least 60% of cases, with or without amyloidosis, the kidneys excrete immunoglobulin fragments known as Bence Jones proteins into the urine. The kidneys exhibit glomerular lesions associated with proteinuria as well as markedly dilated tubules containing proteinaceous casts.

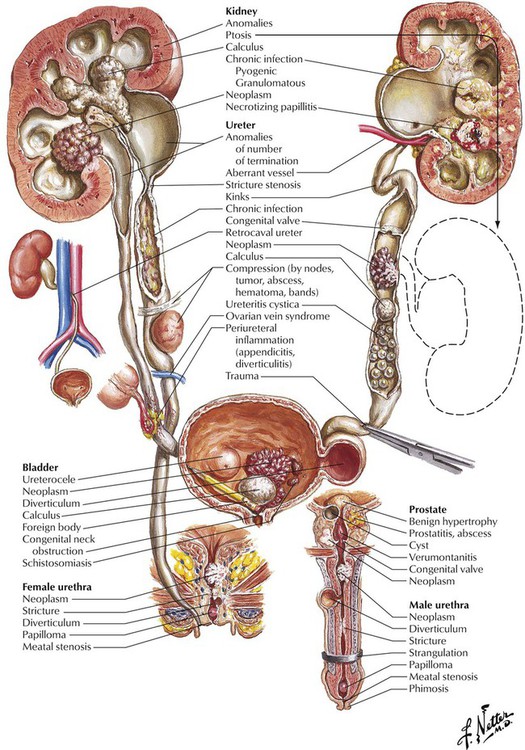

Obstructive uropathy, a common cause of severe or fatal renal failure, is caused by pathologic changes in the urinary tract produced by obstruction to the flow of urine. It may be unilateral or bilateral, depending on the site of obstruction. The likelihood of complications is greatly increased by urinary tract infection, a common finding of obstruction. Acute urinary tract obstruction is often associated with obvious clinical symptoms, whereas chronic obstruction may be insidious or clinically silent. Hydronephrosis, a dilatation of the renal collecting system resulting from severe obstruction to the flow of urine, may be bilateral depending on the site of obstruction. Severe hydronephrosis with renal parenchymal atrophy is unusual except in persons with congenital hydronephrosis. Asymptomatic or silent hydronephrosis, which occurs in adults, may become clinically significant because it increases susceptibility to trauma and infection.

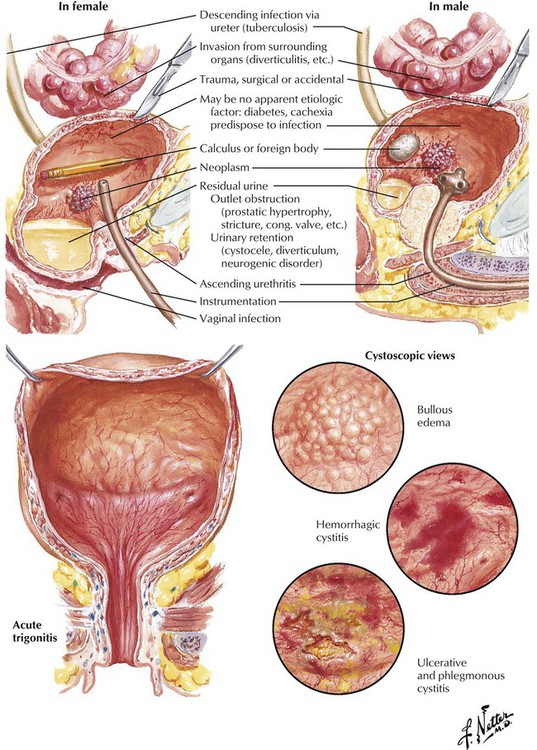

Cystitis results from an inflammation of the urinary bladder. Cystitis usually is a self-limited condition or one easily treated with antibiotics. In some circumstances, such as poorly controlled DM or chronic urinary tract obstruction, cystitis is a severe condition that progresses to involve the upper urinary tract and kidneys and leads to renal failure. In adult women, cystitis is usually limited to the trigone and rarely develops into a severe ulcerative or hemorrhagic disease. In adult men and in children of both sexes, cystitis usually signifies the presence of an underlying anatomical or physiologic abnormality. On cystoscopy, various patterns of involvement may be seen, including cystitis cystica, which is manifest as multiple epithelial-lined cysts. The chief complication of cystitis is spread of infection to the kidneys.

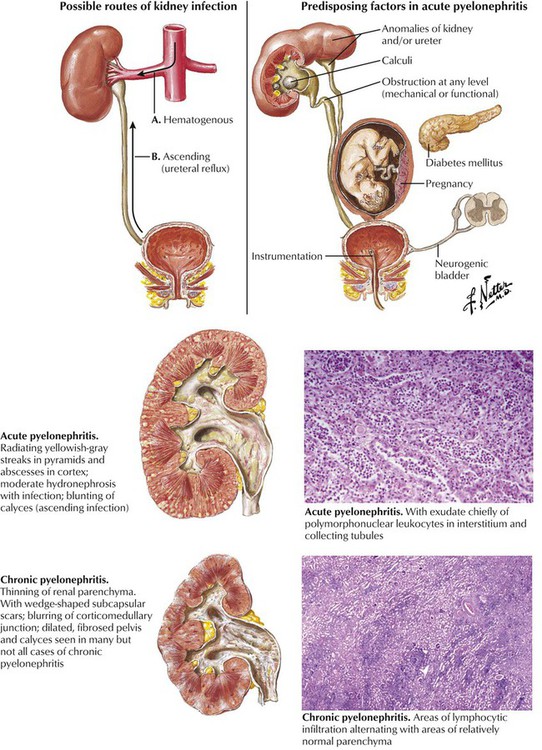

Pyelonephritis, an infectious disease of the kidney, is usually induced by pyogenic microorganisms, particularly Escherichia coli and other gram-negative bacteria. The primary process is inflammation of the renal interstitium and the tubules. In acute pyelonephritis, the swollen kidney exhibits multiple small abscesses seen as linear, yellowish areas radiating continuously from the corticomedullary junction to the surface and sometimes extending through the medulla into the papillae. Microscopically, the yellow lesions correspond to a heavy interstitial infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, with pus formation and liquefaction necrosis. The lesions are generally patchy with preserved glomeruli and vessels. The characteristic gross feature of chronic pyelonephritis is a coarsely granular contracted kidney with significant loss of renal parenchyma in the cortex and the medulla. Chronic interstitial inflammation (lymphocytes, macrophages) is widespread; many tubules are destroyed, and those remaining are dilated, lined by flattened epithelium, and filled with proteinaceous casts.

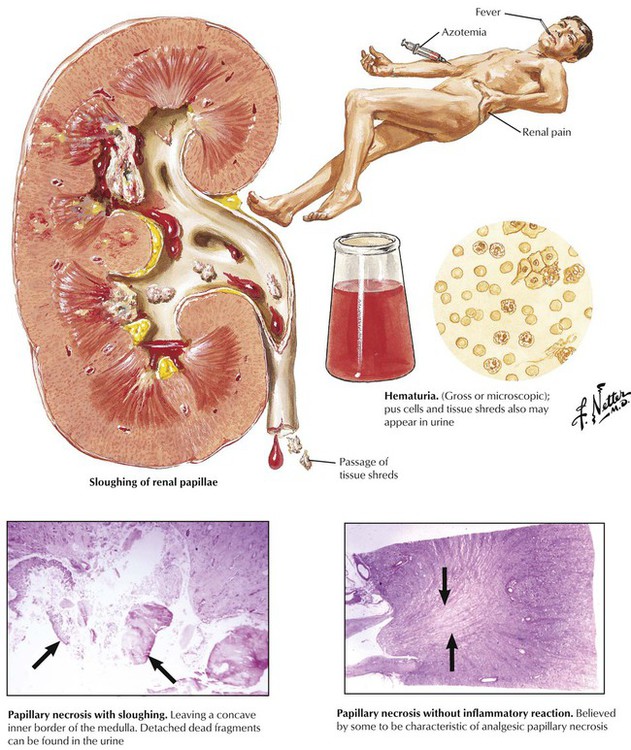

When coagulation necrosis of the renal papillae and portions of the medulla occurs, the necrotic tissue may be sloughed into the renal pelvis and passed into the ureter. The patient typically becomes ill with fever, renal colic, hematuria, oliguria, and azotemia, which may progress to fatal uremia. In some patients, particularly those with long-standing azotemia, sloughing of the papillae may occur over a prolonged period without overt ARF. Papillary necrosis occurs most often in older people and in those with DM or pyelonephritis, particularly if there is lower urinary tract obstruction. In such individuals, a zone of neutrophilic infiltration at the periphery of the necrotic papilla is usually present. In patients who ingest excessive amounts of analgesic drugs, the papillary necrosis seems to result from a chemical toxicity without significant inflammation.

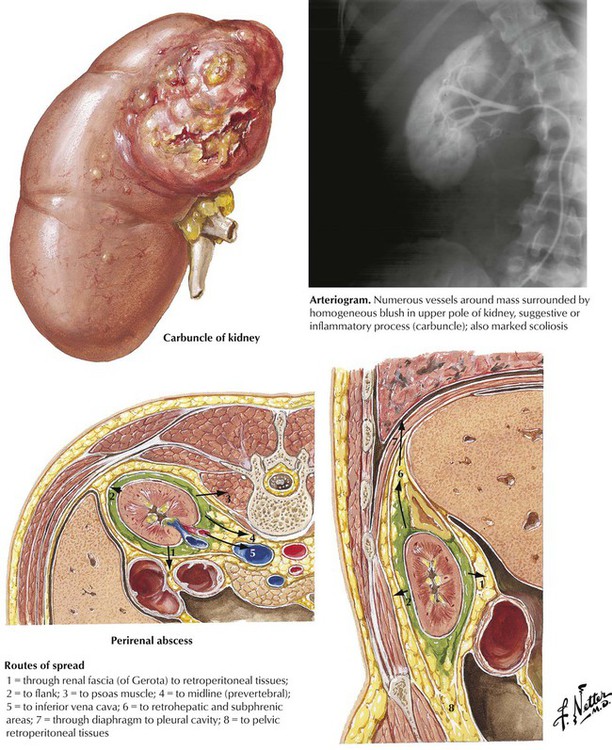

Renal carbuncle and perirenal abscess are septic conditions caused by infections with Staphylococcus species. These conditions, which may begin as an innocuous skin furuncle, reach the renal or perirenal tissue by hematogenous or lymphogenous spread. A renal carbuncle is an abscess in the renal cortex that typically results from the confluence of several smaller abscesses. This lesion occasionally produces a perirenal abscess through rupture into the collecting system or through the capsule. The perirenal abscess usually develops as a primary abscess in the perirenal fat inside the Gerota fascia. Both renal carbuncle and perirenal abscess produce a marked leukocytosis of the blood, with variable findings on urinalysis. An intrarenal or perirenal mass lesion is detected by imaging studies.

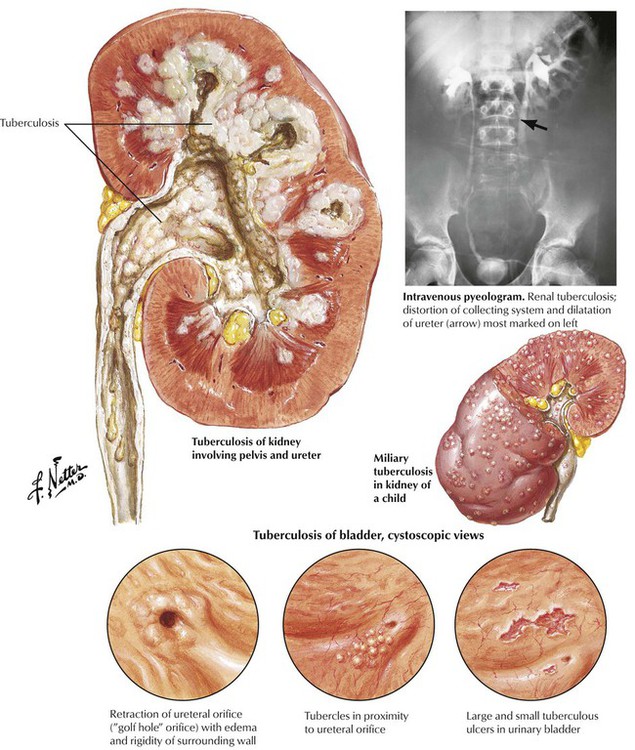

Tuberculosis of the urinary tract develops as a consequence of hematogenous dissemination of the tubercle bacilli (usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis). Urinary tract involvement has a peak incidence between the ages of 30 and 50 years and occurs more frequently in males. Bilateral involvement, particularly of the upper poles of the kidneys, is common. After the initial involvement of the kidneys, spread may occur to other components of the urinary tract. In countries where the dairy industry is closely regulated, the infecting organism is usually the human strain, but infection by the bovine strain is prevalent in other parts of the world. The lesions are those of a caseating granulomatous process with predisposition to cavitation and calcification. The kidneys are a common site of involvement in miliary tuberculosis in children.

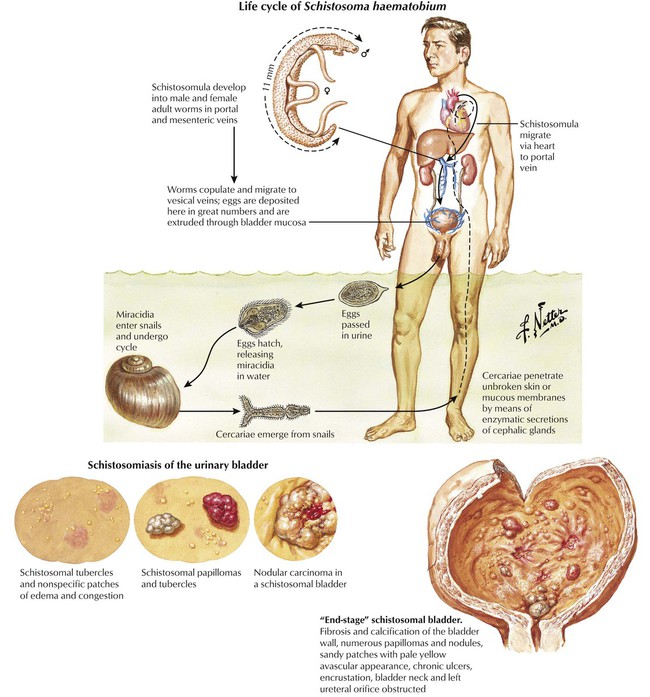

Blood fluke parasites have a worldwide distribution. Infection with Schistosoma haematobium leads to urinary schistosomiasis. In the acute phase of the infection, cercarial penetration produces local skin erythema and itching, which is usually followed in 4 to 6 weeks by a febrile and toxic illness with eosinophilia. Spontaneous clinical resolution occurs, although the adult worm continues to lay eggs. Chronic illness resulting from lesions caused by the eggs occurs months or years later. Initially, a granulomatous reaction occurs around schistosome eggs, producing pseudotubercles. Dystrophic calcification of the eggs and adjacent tissue is common. The progression of the lesions is toward a fibrotic stage, which is frequently associated with anatomical distortion of the genitourinary tract. The chronic infection predisposes to the development of carcinoma of the urinary bladder. The disease may progress to bilateral obstructive uropathy with renal dysfunction.

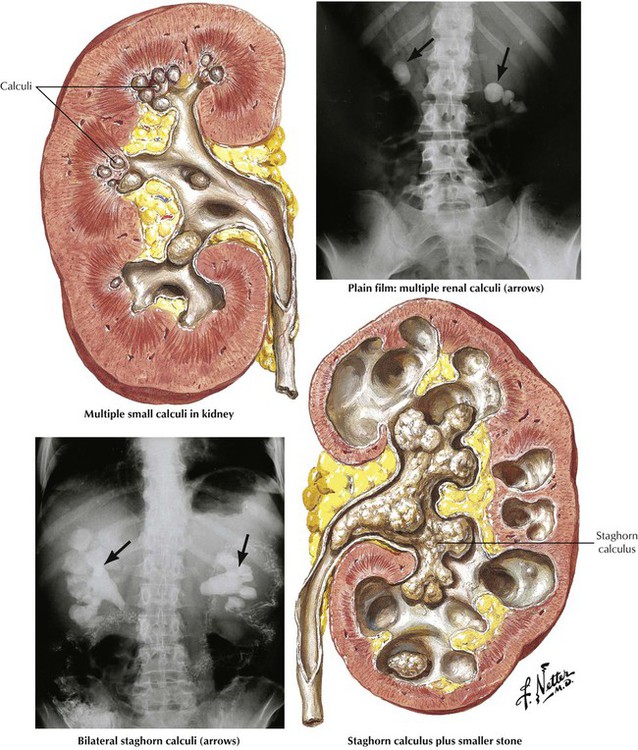

Clinically significant complications of urinary calculi involve up to 10% of the population. The calculi affect men more than women, with peak occurrence between 20 and 50 years of age. The etiology is poorly defined, although factors leading to highly concentrated urine predispose to stone formation. Most stones originate in the kidney and are composed of calcium oxylate and other calcium salts embedded in an organic matrix. Certain metabolic diseases (hyperoxaluria and disorders of amino acid metabolism) predispose to stone formation. Renal calculi may remain in the pelvis of the kidney (staghorn calculus) or pass down the ureter, which produces the severe pain of renal colic. Destruction of renal parenchyma may result from progressive growth of the calculus, obstruction, or infections. Occasionally, calculi form in the ureter or urinary bladder as a result of urinary stasis secondary to various congenital or acquired anomalies.

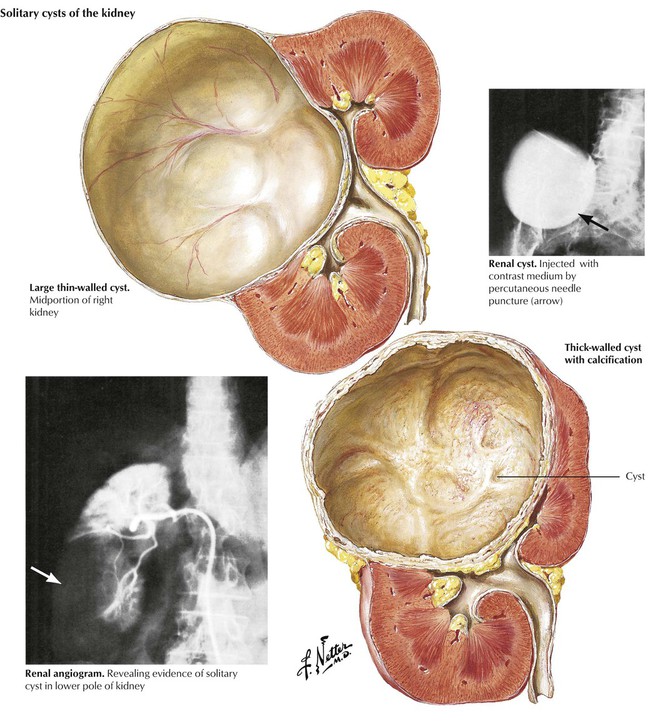

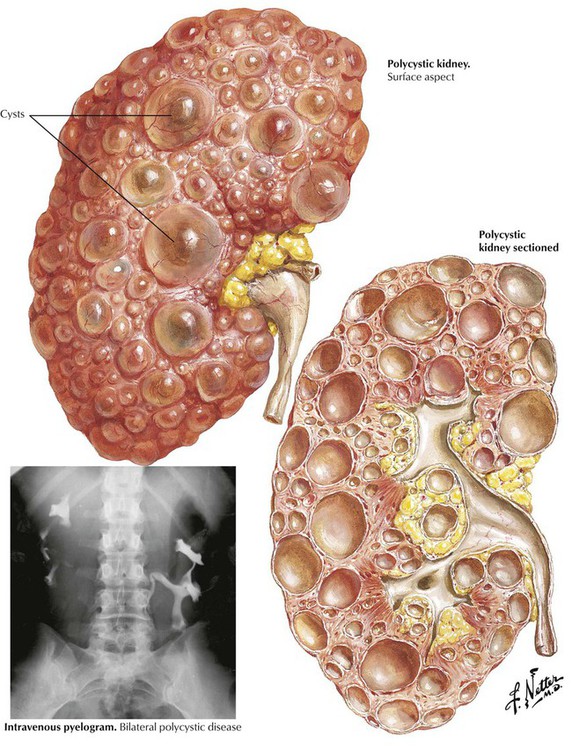

A general classification of renal cystic diseases is as follows: (1) autosomal dominant (adult) polycystic disease of the kidney; (2) autosomal recessive (childhood) polycystic disease of the kidney; (3) unilateral multicystic disease of the kidney (unilateral renal dysplasia); (4) simple cysts (single, multiple, and multilocular); and (5) cysts of miscellaneous origin, such as retention or inflammatory cysts, and cysts secondary to hematoma, Echinococcus infections, pyelonephritis, and other specific diseases. Simple cysts may be solitary or multiple, thin walled or thick walled, trabeculated or multilocular. The cystic fluid may be clear or hemorrhagic, and the wall may occasionally have foci of dystrophic calcification. Rarely, adenocarcinoma of the wall may occur. Simple cysts are usually located in the cortex and bulge through the renal capsule. Sometimes, the cysts may be more deeply located and produce obstruction to urine outflow. Cysts must be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of mass lesions in the kidney.

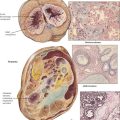

Adult polycystic kidney disease has an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, with individual cases resulting from a mutation of the PKD1 gene on chromosome 16, the PKD2 gene on chromosome 4, or a yet-to-be-localized PKD3 gene. In contrast, infantile or childhood polycystic disease has an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern and represents a severe form of renal dysplasia. Adult polycystic kidney disease is relatively common, occurring in 1 of 400 to 1000 live births and accounting for approximately 10% of chronic renal failure in adults. Kidney damage is a slowly developing but progressive process that eventually reaches clinical significance in all affected individuals surviving into the ninth decade of life. In the more advanced stages, destruction of renal tissue results in azotemia and physical discomfort from the sheer size of the large cystic masses. Hypertension occurs frequently, as do urinary tract infections. Associated conditions include intracranial berry aneurysms. The patients inevitably become dependent on hemodialysis and are candidates for kidney transplantation.

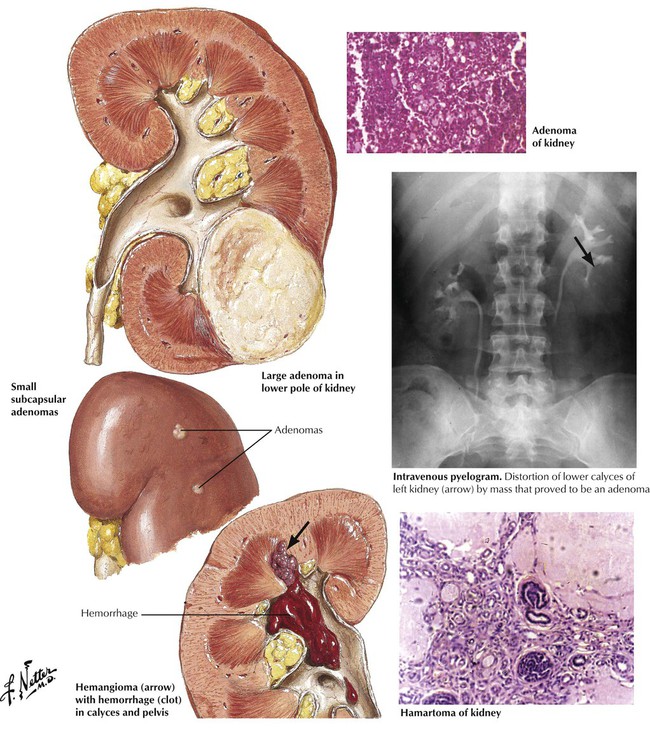

Benign tumors of the kidney may mimic malignant tumors and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a renal cyst. Renal adenomas are typically small cortical nodules, which often grow within small cysts. They are usually papillomatous structures but may have a tubular or alveolar growth pattern. Occasionally, a large, single adenoma is found. The cells of adenomas are usually cuboidal and show well-differentiated cytology and growth pattern. The adenoma should be considered premalignant and prone to give rise to clones of malignant cells. Tumors larger than 3 cm in diameter are likely to metastasize. Connective tissue tumors that arise in the kidney include fibroma, lipoma, myoma, hemangioma, and angiomyolipoma (hamartoma), the latter occurring as part of the tuberous sclerosis complex.

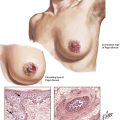

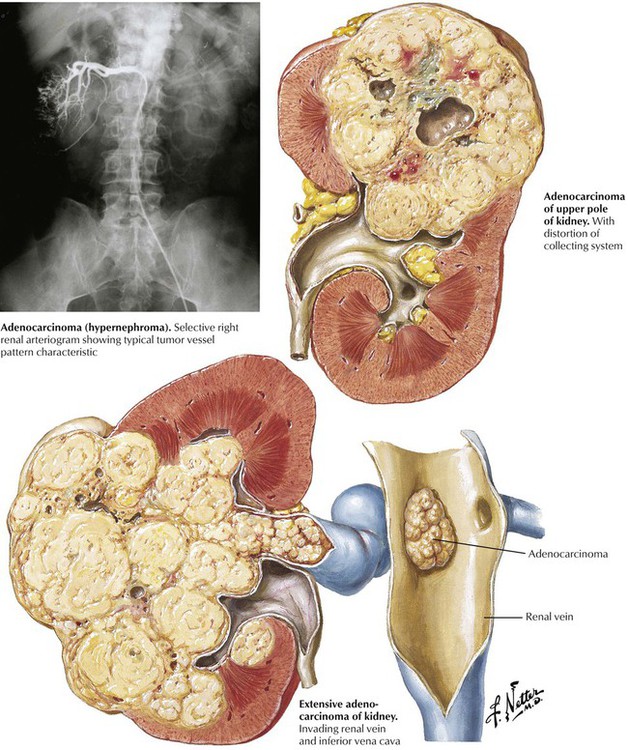

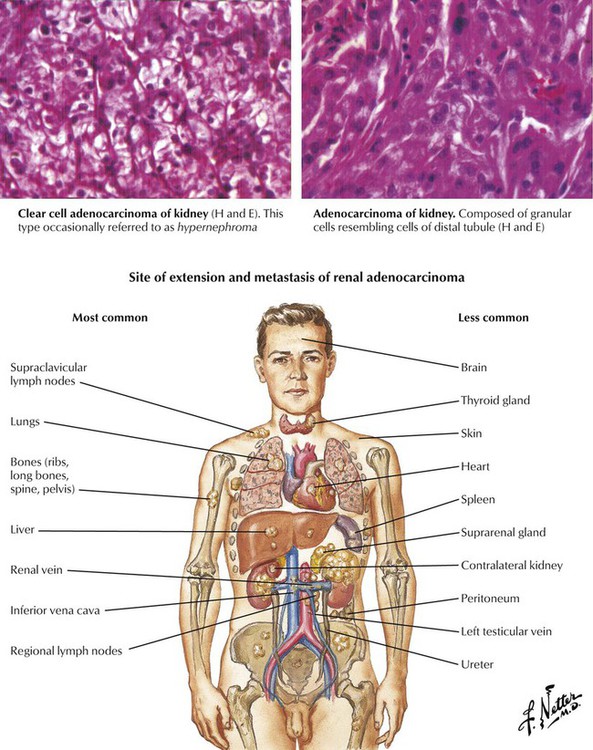

Malignant tumors of the kidney may be primary tumors originating in the parenchyma, pelvis, or capsule or they may be metastatic, usually with bilateral involvement. Fibrosarcoma, myosarcoma, liposarcoma, and angioendothelioma are rare primary tumors. Renal adenocarcinoma, which encompasses all malignant epithelial renal tumors, accounts for approximately three fourths of all renal malignancies, usually occurs in middle age, and affects males twice as often as females. Typically, the unilateral and solitary tumor, which is usually encapsulated, firm, and solid, arises from either pole or the central region of the kidney. Renal vein invasion is common. Growth of the primary lesion may lead to a mass in the flank, microscopic or gross hematuria, and renal colic.Subtypes of renal cell adenocarcinoma (in order of frequency) are clear cell carcinoma (70 to 80%), papillary carcinoma (10 to 15%), chromophobe renal carcinoma (5%), and collecting duct carcinoma (1%). Histologically, adenocarcinoma shows a variety of patterns, including vacuolated clear cells, granular cells, and anaplastic cells. The extent of local spread and the presence of metastases are more important than the histological pattern. Renal cell carcinoma often metastasizes via the blood, but lymphatic spread also occurs.

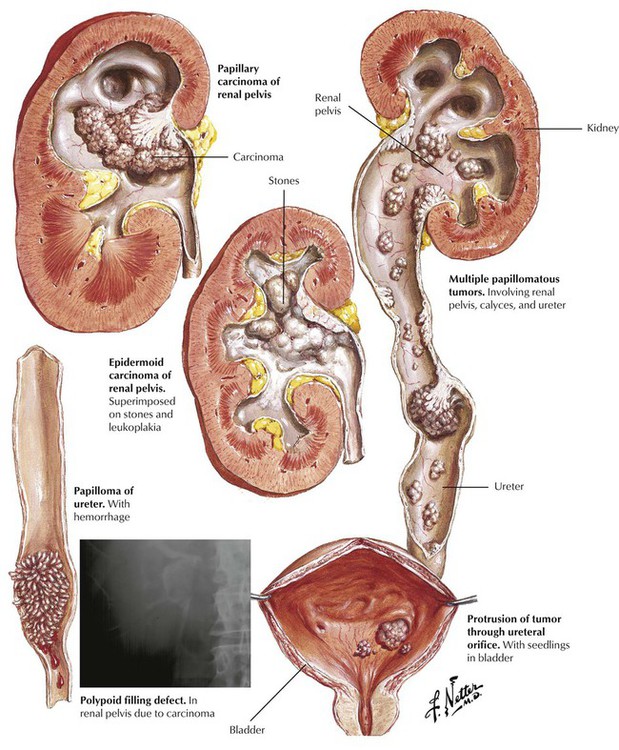

Tumors of the renal collecting system, which usually arise from the epithelium as urothelial cell (transitional cell) papillomas or urothelial cell carcinomas, comprise approximately 10% of renal tumors. Squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and metastases are less common. Urothelial cell papilloma is cytologically bland but must be considered premalignant, whereas urothelial cell carcinomas exhibit overt cytologic atypia. Urothelial cell tumors of the renal pelvis, ureter, and bladder occur predominately in older men. They may be single or multiple and are usually papillomatous and unilateral. Squamous cell (epidermoid) carcinoma is frequently associated with renal calculi and infection. The lesions, which are usually flat and firm and often ulcerated, are likely to invade the renal parenchyma and metastasize early. These tumors usually present with microscopic or gross hematuria.

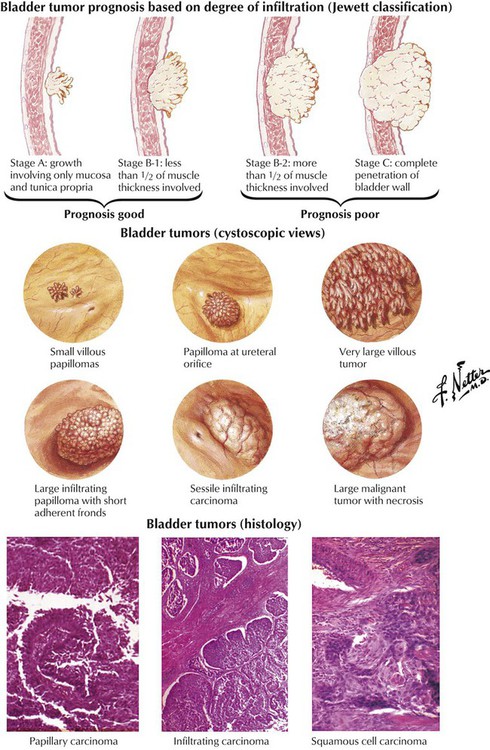

Urinary bladder tumors typically arise from the mucosa and are composed of urothelial cells. The full spectrum of lesions includes papillomas, papillary lesions of low malignant potential, flat urothelial carcinoma, and papillary carcinomas. Other forms of bladder cancer include undifferentiated carcinomas, squamous (epidermoid) carcinomas (in areas of leukoplakia), adenocarcinoma (which may be mucin producing), and the rare epithelial mesenchymal tumors. The lesions occur principally in older adults, mostly males, and in 25% of cases are multiple. Exposure to and ingestion of environmental toxins are important in the pathogenesis of these lesions. The prognosis for patients with bladder tumors is strongly influenced by the degree of tumor infiltration of the bladder wall, or tumor stage (Jewett classification), but histologic grading of the degree of differentiation and cytologic atypia also provides useful information (Broder classification).

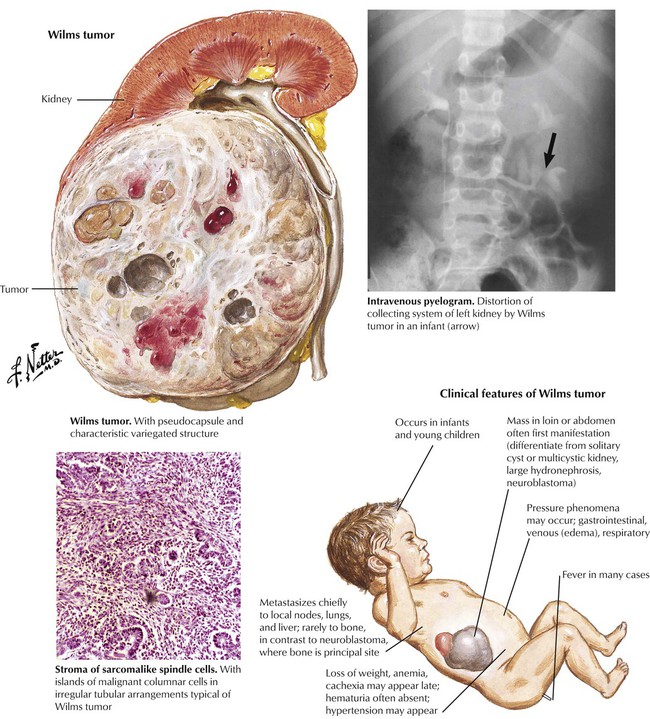

The differential diagnosis of an upper abdominal mass in an infant or child includes the more common benign conditions such as ureteropelvic junction obstruction, with or without associated pyelonephritis, multicystic kidney disease, and malignant tumors, particularly neuroblastoma and nephroblastoma (Wilms tumor, WT). Nephroblastoma is a usually unilateral, intrinsic renal neoplasm containing both epithelial and connective tissue elements with various degrees of cellular differentiation. It is thought to arise from the metanephrogenic blastoma. Definitive differential diagnosis and rapid treatment are important because the tumor has a propensity for metastasis, primarily to lungs, the liver, the lymph nodes, and, less frequently, the bones. The prognosis has improved with the combined use of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery.

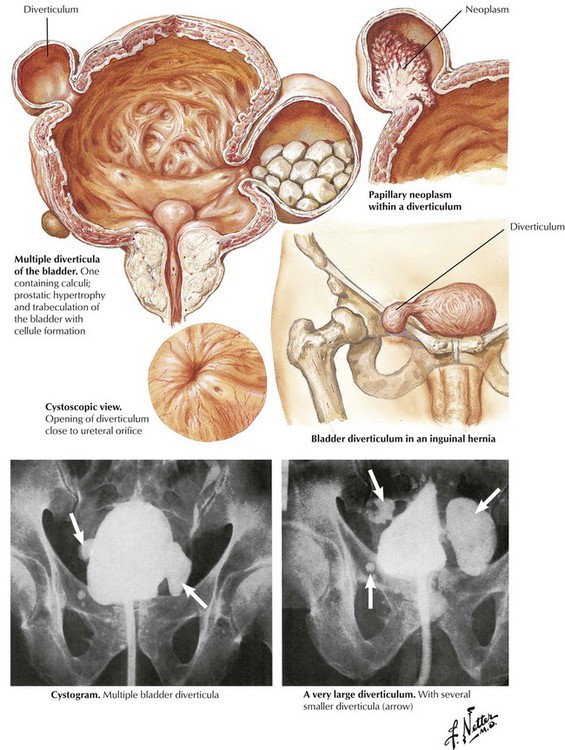

Diverticula of the bladder begin as small outpouchings or evaginations of the bladder wall between hypertrophied muscle bundles in the setting of bladder outlet obstruction. As obstruction progresses, weakening of the detrusor muscle, the external muscle layer of the bladder, gradually allows the formation of one or more true diverticula. The opening of the diverticulum is usually narrow, the lumen is covered with urothelium, and the wall is constructed primarily of connective tissue with focal strands of muscle fibers. The incidence of bladder diverticula is much greater in men and is usually a consequence of bladder outlet obstruction resulting from prostatic enlargement. Congenital diverticula are likely secondary to obstruction.

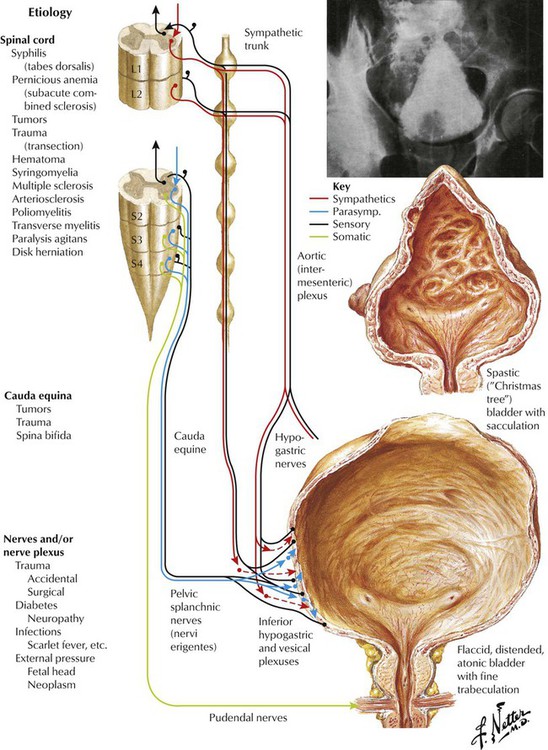

Neurologic impairment of bladder function may result from a variety of conditions. The site of the injury or disease determines the nature of the abnormality because the innervation of different parts of the bladder arises from different portions of the nervous system. Treatment of neurogenic bladder is aimed at prevention of eventual damage to the upper urinary tract from infection, urolithiasis, and obstruction. When effective control is absent, chronic neurogenic bladder may cause chronic urinary infection with secondary stone formation, leading to deterioration of kidney function and eventual uremia. Prevention includes use of indwelling urinary catheters, good hydration to maintain high urine volume, bladder irrigation to dissolve calcium salts, and treatment with antibiotics.