9 Kidney and Urinary Tract Disease

Presentation of kidney and urinary tract disease

• Patients’ complaints are directly related to the urinary tract or urine output, e.g. frequency, dysuria, burning micturition, urgency, colic, polyuria, nocturia, haematuria, oliguria, and anuria.

• Discovery of abnormal laboratory findings during routine investigations, e.g. proteinuria, haematuria, elevated plasma creatinine, electrolyte and acid–base disturbances.

• Symptoms and signs of renal failure (e.g. uraemia, anaemia, anuria, hypertension and oedema) in the absence of prior renal disease.

• Discovery of renal and urinary tract disease as part of involvement in systemic disease, for example:

Information

Fluid balance and electrolytes: assessing fluid status

Clinical assessment

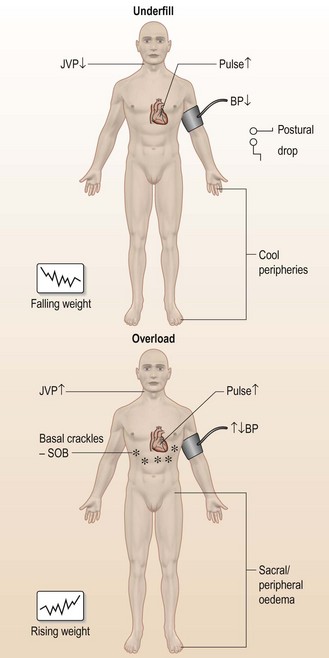

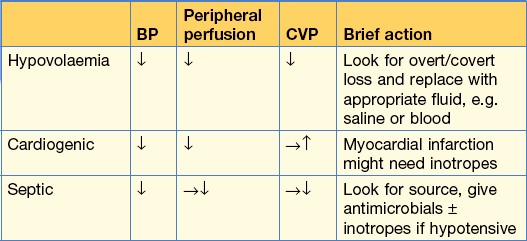

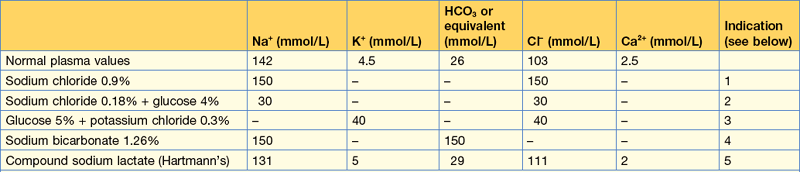

Take a quick history, particularly of fluid and electrolyte intake (oral or intravenous) and output (renal, GI tract or skin), then examine the patient (Fig. 9.1, Table 9.1).

| Useful | Not so useful | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical examinations | BP (especially postural or post-exercise drop) | Skin turgor |

| Oedema | Eye turgor | |

| JVP | Mucous membranes | |

| Peripheral perfusion | ||

| Pulse | ||

| Basal crackles | ||

| Charts | Serial weight (on same machine) | Fluid balance (input/output) |

| Additional tools | CVP line – use dynamically | CVP – absolute |

| CXR | Urine Na+ | |

| Pulmonary artery flow catheter | Osmolality |

Case history (1)

He is normally fit and well and he wonders whether he has some form of severe gastroenteritis.

Figure 9.1 (a) shows the other signs of hypovolaemia.

Investigations

Management

An emergency CT scan confirmed the haemothorax and an intercostal tube drain was inserted.

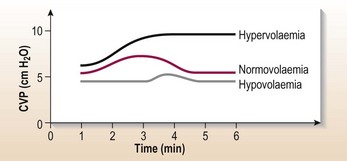

A CVP line was inserted to assess fluid balance. Fluid challenge (Table 9.2 and Fig. 9.2) indicated hypovolaemia, and blood transfusion (2 units) was started with repeated checks on his fluid status.

A laparotomy was performed and 20 cm of small bowel resected.

Fluid balance and electrolytes: sodium problems

What are you actually measuring when you measure the serum sodium?

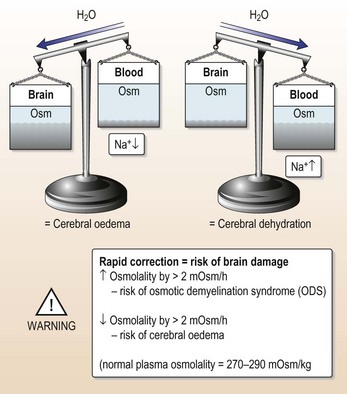

Using this concept you can describe how serum Na+ becomes abnormally low (hyponatraemia) or high (hypernatraemia) (Table 9.3).

| Ratio (Na+ : water) | Extracellular water |

|---|---|

| Hyponatraemia | |

| Water ↑ | → or ↓ |

| Water ↑ > Na+ ↑ | ↓↓ |

| Na+ ↓ | ↓ |

| Hypernatraemia | |

| Water ↓ | → or ↓ |

| Water ↓ > Na+ ↓ | ↓↓ |

| Na+ ↑ | ↑ |

How do I work out why?

The key is to determine the extracellular water. Examine the patient (see Fig. 9.1).

Management

On examination there were no features of fluid depletion, which excludes true Na+ depletion.

Action

• Stop IV fluids, restrict oral fluids to 1 litre daily and food as requested by the patient. 48 hours later her serum sodium is 132 mmol/L.

Other causes of hyponatraemia

• Diuretic therapy: particularly loop diuretics cause large renal losses of salt and water and metabolic alkalosis.

• Severe heart failure, advanced liver cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome: hyponatraemia with increased total body sodium and even greater excess of water resulting in ascites and oedema. Plasma osmolality is low. Increased water orally continues in the face of salt restriction, diuretic therapy or both and will aggravate the ascites and oedema.

• Syndrome of inappropriate ADH production (p. 459).

• Pseudohyponatraemia: e.g. hyperlipidaemic states where sodium is confined to the aqueous phase or monoclonal gammopathies, hyperglycaemia (10 mmol rise reduces sodium by approximately 2 mmol).

Hypernatraemia

Hypernatraemia is defined as sodium > 145 mmol/L.

• Iatrogenic: IV infusion of hypertonic sodium bicarbonate, hyperalimentation by IV route or nasogastric tube, sodium chloride tablets, sea water drowning or mineralocorticoid excess; total body sodium is elevated in these conditions. Signs are of hypervolaemia.

• Impaired thirst/unconscious patient: total body sodium is low because of both sodium and water deficit but water losses are greater than the losses of sodium. Signs are of hypovolaemia.

• Osmotic diuresis, e.g. diabetic ketoacidosis, radiocontrast, mannitol: total body sodium is low because of both sodium and water deficit, but water losses are greater than sodium losses. Urine is not maximally concentrated despite hyperosmolar state, in contrast to GI losses of sodium and water where urine is maximally concentrated. Signs here are of hypovolaemia.

• Water loss, e.g. diabetes insipidus: normal total body sodium. Signs are of euvolaemia.

Treatment

• Avoid rapid correction (Fig. 9.3). Serum Na+ should not fall > 1 mmol every 2 hours, i.e. 10 mmol/24 hours.

• Initially give IV 0.45% saline. This is followed by 5% glucose with 20 mmol/L K+ with frequent monitoring of volume status and serum Na+ level. This stays in the extracellular compartment (see assessing fluid status, p. 223).

Patient stopped passing urine

What should you do?

Take a detailed history of type of surgical procedure. Ask about GI bleeding, dehydration or other fluid losses, nephrotoxic drugs, drugs associated with hypersensitivity reaction causing tubo-interstitial nephritis (e.g. penicillins, NSAIDs, cephalosporins), evidence of previous renal insufficiency, and any radiological procedure with contrast enhancement. Anuria usually means obstructive uropathy or vasculitides rather than acute tubulo-nephritis (ATN); evidence of these conditions should be sought.

On examination the patient has a tachycardia of 110 bpm with a low BP 90/50.

Common causes of poor urinary output

• Urine retention: always catheterise.

• Dehydration: assess fluid status (see Fig. 9.1). Look at fluid balance charts.

Initial management

This man is fluid depleted and needs fluid replacement (Table 9.5):

Still no urine?

• Are you certain the patient is adequately fluid replete?

• Check that the urine catheter is not blocked or misplaced.

• Give a loop diuretic, e.g. furosemide.

• The patient might now have established acute kidney injury. Refer to nephrologist.

Fortunately this man responded to fluid replacement and produced urine, intitially 50 mL/hour.

Acute heart failure

What has gone wrong?

| Grade | GFR Criteria | UO Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Risk | SCr × 1.5 or GFR decrease >25% (within 48 hr) | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/h × 6 h |

| Injury | SCr × 2 or GFR decrease >50% | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/h × 12 h |

| Failure | SCr × 3, GFR decrease >75%, | UO < 0.3 mL/kg/h × 24 h |

| SCr > 350 µmol/L | ||

| with an acute rise > 40 µmol/L | ||

| Loss | Persistent AKI > 4 weeks | |

| ESKD | Persistent ESKD > 3 months |

SCr = serum creatinine; UO = Urinary output; ESKD = end stage kidney disease.

(Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C. Acute kidney injury. Lancet 2012; 380: 756–766.

There is a new consensus definition that merges RIFLE criteria and the Acute Kidney Injury network definition (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (K-DIGO) group 2012).

Clinical suspicion of renovascular disease

• Most patients will have disseminated atheroma with missing pulses and/or bruits and a history of smoking.

• Abdominal/renal bruits (although they have a very strong association with renal artery stenosis (RAS)) are rare.

• ‘Flash pulmonary oedema’ (without an obvious precipitant) is a good predictor of renovascular disease.

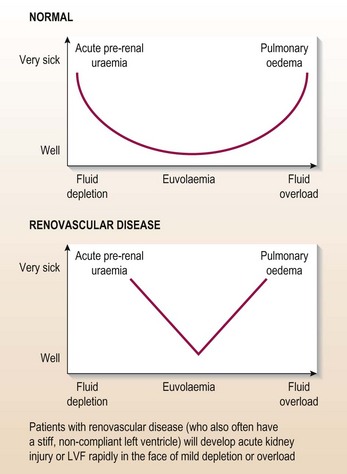

• Brittle response to volume loading or off-loading (Fig. 9.5).

Note: her renal function was abnormal at presentation.

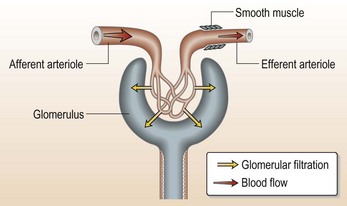

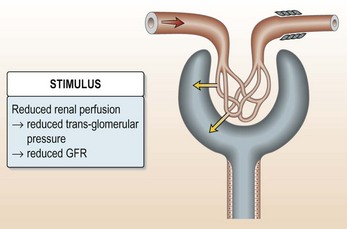

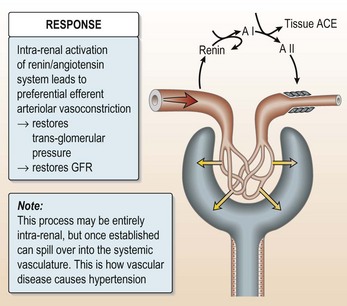

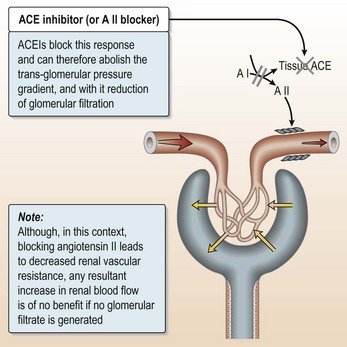

ACE inhibitors can cause acute kidney injury in patients with renovascular disease (Fig. 9.6).

How should patients like this be managed?

The key to successful management is very careful fluid control.

Managing acute heart failure (AHF) in the presence of suspected renovascular disease

• Treat the pulmonary oedema: it is a dangerous and very distressing condition.

• Avoid ACEIs/AII blockers: use other vasodilators (this patient was given captopril!).

• Avoid rapid volume off-loading: titrate the diuretic dose against renal function.

• Insert a CVP line and use it properly (see Fig. 9.1).

• Examine (and weigh) the patient regularly: use low-dose dopamine (can be given via peripheral line at 2.5 mg/kg/min) for its natiuretic effect if no response to initial therapy.

Renal imaging investigations

• Ultrasound: unequal renal size (> 2 cm difference) is a good predictor of renovascular disease but its absence does not exclude RAS. Duplex ultrasound is used to demonstrate renal artery perfusion.

• Isotope renography: unequal function, slow transit and altered dynamics with captopril are all suggestive of renovascular disease. In experienced hands and with good renal function, its sensitivity and specificity are 70% (creatinine < 150 µmol/L); however, in inpatients with severe renal impairment its sensitivity falls below 30%.

• MR angiography is increasingly used to visualise the renal arteries.

• Intra-arterial angiography: the gold standard – should be done by experienced radiologists with minimal contrast load.

On the natural history of atheromatous renovascular disease

• ACEI/AII blockers will cause ARF only if both kidneys are affected by RAS, or if only one functioning kidney is present. However, the atheroma is diffuse and progressive. Complete renal artery occlusion with total loss of renal function on one side is usually clinically silent.

• Anatomical renovascular disease is very common and much of it is not physiologically significant (but you can’t tell which is which until it is too late).

• Small vessel (intra-renal) disease behaves identically to main renal artery disease (but you can’t treat it).

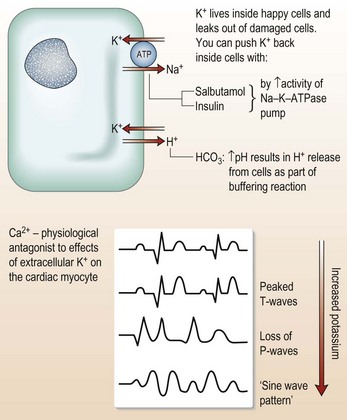

Hyperkalaemia

Don’t let your patient die tonight!

What do you do next?

As K+ > 6.5 mmol/L:

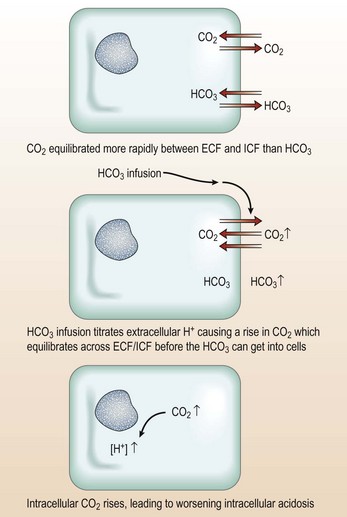

• Get K+ inside cells: 50 mL of 50% glucose with (or followed by) 10 U insulin. IV 50 mL sodium bicarbonate 8.4% is given over 1 h for severe acidosis pH < 6.9. Salbutamol infusion is now rarely used.

Now you have time to stop and think. The K+ is telling you that something has gone badly wrong. Find it and treat it!

Quick and simple ways to stop or reverse underlying causes of raised K+

As you can’t promptly reverse the cause

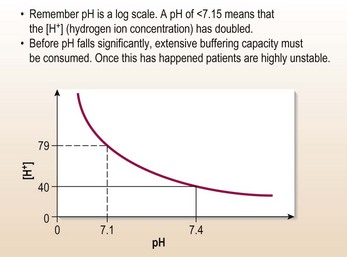

The acidotic patient

How to manage severe acidosis

Problems with any of these will contribute to acidosis and must be corrected.

Identify and treat the underlying problem

Note: all the above result in metabolic acidosis with high anionic gap.

Examples of normal anionic gap acidosis (hyperchloraemic acidosis):

Acute kidney injury

What are your priorities?

1 Safety

In this case, the patient has a K+ of 5.6 mmol/L and his fluid status is OK. At this stage, review/stop any drug therapy. Now, you have to consider:

Guide to indications for dialysis

There is no magic level of urea or creatinine. Dialysis is indicated:

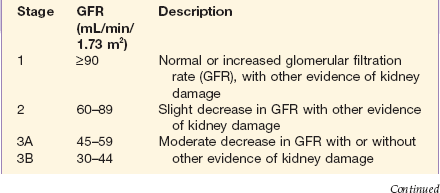

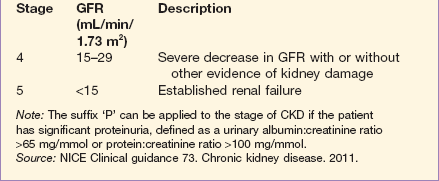

Chronic kidney disease

Investigations

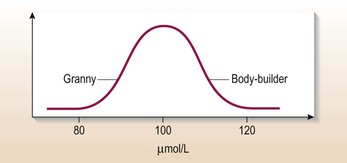

Estimation of creatinine clearance

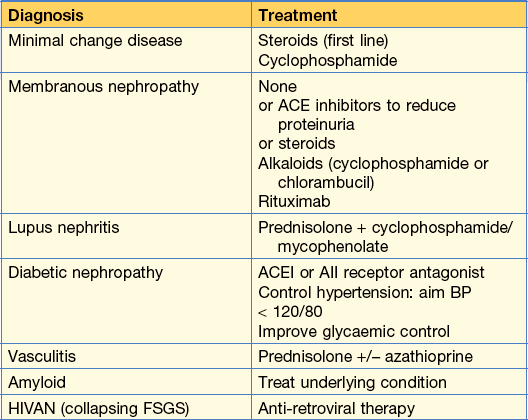

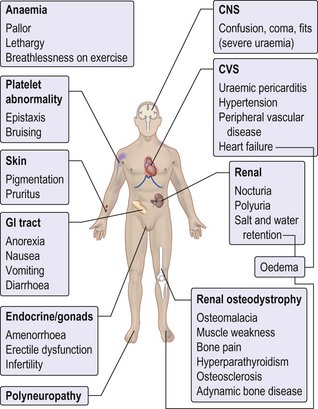

Clinical features seen in CKD are shown in Figure 9.10.

Figure 9.10 Symptoms and signs of chronic kidney disease.

From Kumar and Clark Clinical Medicine 8th edn, 2012.

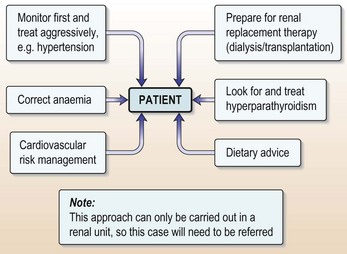

How do you manage this case?

Remember

• CKD is an insidious condition with no specific symptoms. In some cases, patients do not present until they have reached the stage when dialysis is required

• Preparing the patient for dialysis is a specialist task: refer!

• CKD is a major cardiovascular risk factor: the average dialysis patient is approximately 20 times at risk.

Preparing the patient

Specific conditions:

Hyperparathyroidism

Multisystem vasculitis/acute glomerulonephritis

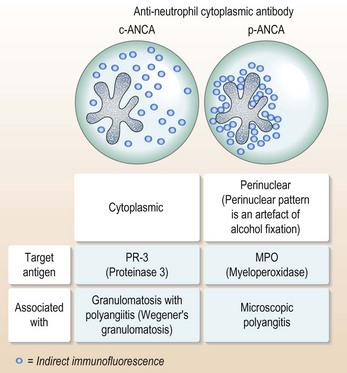

Inflammatory autoimmune vasculitis: microscopic polyangiitis/Wegener’s granulomatosis

At this point the diagnosis is more obvious but these diseases respond well to treatment if diagnosed early.

Pulmonary haemorrhage

• Most common disease-related cause of death in ANCA +ve vasculitis and anti-GBM (glomerular basement membrane) disease (Goodpasture’s syndrome).

• CXR appearances very variable but usually patchy alveolar shadowing (can mimic, or be accompanied by, pulmonary oedema or chest infection).

• Often precipitated by pulmonary oedema/infection/smoking.

• Can be diagnosed non-invasively by finding increased KCO (carbon monoxide (CO) binds to blood and gives falsely elevated KCO).

How to diagnose multi-system vasculitis

If you find microscopic haematuria in a patient with non-specific malaise/myalgia:

• Enquire specifically for suggestive symptoms:

• Don’t assume that microscopic haematuria is due to UTI: send an MSU.

• If there are suggestive symptoms or signs: discuss with a nephrologist.

• If there are no suggestive symptoms or signs but MSU is –ve for a urinary tract infection: Check renal function; if it is abnormal, discuss with a nephrologist.

ANCA points (Fig. 9.12)

• False +ves occur in situations of polyclonal B-cell activation (usually on immunohistology but not against specific target antigens).

• ANCA –ve small vessel vasculitis can be clinically and pathologically identical to ANCA +ve vasculitis.

• Changes in antibody titre might be unrelated to, lag behind or precede changes in disease activity in different patients.

Other rapidly progressive glomerulonephritides (GN)

• Goodpasture’s disease is rare: it is classically described as a ‘one-hit’ disease and is less likely to be preceded by a non-specific prodrome than ANCA +ve vasculitis.

• IgA nephropathy, mesangiocapillary GN due to cryoglobulins, and diffuse proliferative GN in SLE can all present with a rapidly progressive, crescentric nephritis.

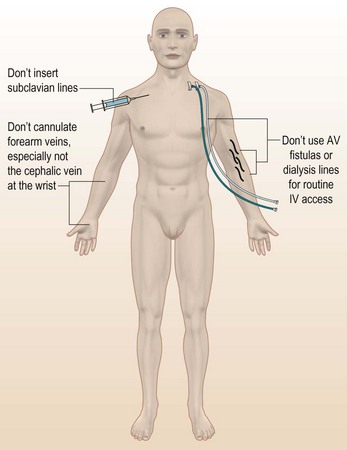

Intercurrent illness in dialysis and transplant patients

Remember

• Don’t give blood transfusion in a dialysis patient unless a nephrologist tells you to – you could precipitate lethal hyperkalaemia and volume overload (and the normal methods of treating these complaints will be ineffective)

• Also: even if your patient survives, you might sensitise him or her to HLA antigens in the blood, thereby denying the chance of a renal transplant

• As a general rule: dialysis patients should not be transfused while on dialysis.

Other things not to do in dialysis patients

Things to watch out for in dialysis patients

• Vascular disease: ischaemic heart disease is very common in dialysis patients – even young ones. It is often unmasked by anaemia.

• Infection: dialysis patients are significantly functionally immunosuppressed. They cope poorly with sepsis and rapidly become systemically unwell. Infections in access sites (lines, fistulae, PD catheters) are common and might not be clinically evident, e.g. subacute infective endocarditis and osteomyelitis – always think of these complications.

• Electrolytes: haemodialysis patients are often chronically hyperkalaemic pre-dialysis (and invariably hypokalaemic immediately post-dialysis). They will often present with hypercalcaemia (too much vitamin D or Ca2+-based PO4-binders) or hypocalcaemia (too little).

• Poorly compliant patients are routinely hyperphosphataemic; if they then start taking their ‘prescribed’ doses of vitamin D (1-α calcidol) and Ca2+-based phosphate binders, their Ca2+ × PO4 product might exceed 7 mmol/L, precipitating ectopic calcification.

Beware drug interactions that matter in transplantation

Nephrotic syndrome

Nephrotic syndrome is not a diagnosis but a set of signs and symptoms:

• Proteinuria: usually > 3 g per day

• Hypercholesterolaemia: this is a secondary phenomenon due to increased liver synthesis associated with increased protein synthesis:

• Hypertension, which accompanies the fluid overload

• Thrombophilia: nephrotic syndrome is associated with an increased clotting tendency and risk of thromboembolic disease. It is also a secondary condition. However, while the patient is nephrotic, anti-coagulation is indicated, especially in membranous nephropathy.

Remember

In nephrotic syndrome there is a reduction in relative circulating volume in the presence of oedema.

Haematuria without albuminuria

Aetiology

• Systemic: fever, anti-coagulant therapy, sickle-cell trait or disease, strenuous exercise or coagulopathies.

• Renal: glomerulonephritis (GN; IgA nephropathy, Alport’s, thin basement nephropathy), interstitial tubulonephritis, renal infarcts, TB, polycystic disease, papillary necrosis, neoplasm, trauma, vascular malformations.

• Urinary tract: calculi, foreign bodies, neoplasms, endometriosis, trauma, infections.

History

• Menstrual history to exclude vaginal cause of blood in urine.

• Frequency, urgency, dysuria or urethral discharge suggests bladder or urethral involvement.

• Pain or colic might be seen with stones, obstruction, infarction, polycystic kidney disease (PCKD).

• Bleeding at the beginning of micturition suggests urethral cause whereas terminal bleeding is associated with prostate or bladder pathology.

• Rectal or perineal pain suggests prostatitis.

• Weight loss might suggest a neoplasm.

• History of blood dyscrasia or anti-coagulant therapy: anticoagulant therapy usage and haematuria should be investigated further for underlying lesions of urinary tract.

• Family history of PCK, sickle-cell disease or GN (Alport’s or thin basement nephropathy).

• Upper respiratory tract infections or gastroenteritis: suggests exacerbations of IgA nephropathy.

• History of easy bruising or vasculitic rash, arthralgia and abdominal pain suggests Henoch–Schönlein purpura. Occasionally anti-GBM disease, SLE or vasculitis can present as isolated haematuria.

Physical examination:

• Look for elevated blood pressure or oedema (usually implies renal lesion).

• Bilaterally palpable kidneys (PCK).

• Unilateral mass (neoplasm or cystic or hydronephrotic kidney).

• Fever and tenderness over renal angle (pyelonephritis).

• Tender prostate (prostatitis).

• Presence of atrial fibrillation or valvular heart disease suggests embolism or renal infarction.

• Presence of petechiae, ecchymosis, lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly may signal blood dyscrasia or clotting disorder.

Investigations

• Complete urinalysis: polarised microscopy may reveal dysmorphic RBC (glomerular origin) or isomorphic RBC (urothelial origin). Pyuria and haematuria with bacterial growth suggest UTI. No bacteriological growth triggers search for TB

• Ultrasound scan of kidneys and bladder with residual bladder volume assessment

• IVU/CT: stones and urinary tract lesions can be missed on ultrasound scan alone

• Cystoscopy is the best procedure for evaluating urinary tract after KUB/CT

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

Information

• Frequency is defined as voiding every 2 hours or more than seven times per day. A variety of factors can affect voiding intervals, including fluid intake, drugs (diuretics), alcohol and caffeine. Patients with polyuria from any cause complain of frequency with an increased urine flow. By contrast, bladder inflammation can cause frequency without an increase in urine flow.

• Urgency is described as powerful sensation to void, regardless of bladder volume. Typically, voided volumes of these patients are small – much less than the patient’s normal maximum bladder capacity. Urgency is often caused by bladder inflammation but prostatic enlargement and external compression of the bladder by masses (as in pregnancy) can also generate the feeling of urgency.

• Dysuria (painful micturition) suggests irritation or inflammation in the bladder neck or urethra, usually because of bacterial inflammation.

Physical examination

Investigations

• Urinary dipstix are positive for both nitrite and leucocyte esterase.

• Urine microscopy: pyuria, bacteriuria and leucocyte casts are consistent with UTI.

• Mid-stream urine specimens sent for culture and sensitivity show E. Coli 105 organisms/mL.

• Full blood count, serum urea and electrolytes and blood cultures show no abnormality.

• An abdominal ultrasound showed no abnormality of the right kidney. Ultrasound should be performed when pyelonephritis is suspected to rule out calculi obstruction and incomplete emptying.

How would you manage this patient?

• Cefuroxime (750 mg 8-hourly) for 3 days, then switch to oral therapy as per sensitivities

• Ciprofloxacin (500 mg oral × 2 daily if no sensitivities are available)

She made a good recovery.

Renal and ureteric colic

Aetiology

• Renal colic is usually caused by stretching of the renal capsule due to acute inflammation or bleeding within the kidney. Acute pyelonephritis, an expanding cyst or an acute expansion of the renal pelvis due to pelviureteric obstruction by calculus or blood clot are the usual causes.

• Ureteric colic is often caused by the passage of a calculus, sloughed papilla or blood clot.

• Renal stones are usually calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate and caused by hypercalciuric or hyperoxaluric states. Other types of stones are struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) stones, which are caused by urea-splitting organisms, cystine stones (the result of an inherited disorder of cystinuria) and urate stones (idiopathic or hyperuricosuric state).

In the history, ask about:

• Pain: this is usually associated with GI symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension).

• Chills, fevers and increased frequency are common.

• Age at which symptoms of stones were first noted.

• Family history of nephrolithiasis.

• History of fractures or prolonged immobilization.

Physical examination

The physical examination is usually unremarkable except for the presence of flank tenderness.

How would you investigate this patient?

• Urinalysis: the urine might be normal despite multiple calculi. Macroscopic or microscopic haematuria is common. Pyuria with or without bacteria may be seen.

• CT-KUB (CT of kidney, ureter and bladder) is carried out during the episode of pain; a normal CT excludes the diagnosis of pain due to calculous disease. The CT-KUB appearances in a patient with acute left ureteric obstruction are shown in Figure 9.14.

Cause of stone formation

• Urinary excretion of calcium, phosphate, oxalate, urate, cystine should be performed on at least two separate occasions.

• Morphological and biochemical analyses should be performed on all the stones that are passed.

This patient was advised to take a high fluid intake and dietary oxalate restriction (refer to a dietitian).