10 Kidney and urinary tract disease

Approach to the Patient

Clinical presentations

Presentation with particular renal syndromes

Patients can present with the syndromes shown in Table 10.1.

| Syndrome | Clinical findings |

|---|---|

| Asymptomatic proteinuria ± microscopic haematuria | Protein and/or blood on urine dipstick ± renal impairment |

| Nephrotic syndrome | Proteinuria +++ Hypoalbuminaemia Peripheral oedema |

| Nephritic syndrome | Microscopic haematuria and proteinuria Renal impairment Hypertension |

| Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis | Rapidly worsening renal function with red cell casts in an active urinary sediment |

| Macroscopic haematuria | Visible bloody discoloration of the urine |

Conditions that may be associated with renal disease

Consequences of renal disease

Examination of the urine

Evaluation of Renal Function

Glomerular disease

Measuring GFR

• Equations used to estimate GFR in clinical practice

Tubular disease

See p. 351 for the diagnosis and management of acute and chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis.

Imaging in renal disease

Uroradiology

Renal biopsy

Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

Glomerular Disease

Nephritic syndrome

Nephrotic syndrome

Nephrotic syndrome presents with:

Nephrotic syndrome is the result of damage to the glomerular filtration barrier. The barrier is made up of the endothelium, the GBM, and podocytes and their slit diaphragms. Both molecular size and charge affect the selectivity of the barrier, which is disrupted in the nephrotic syndrome.

Investigations of glomerular disease

Management of glomerular disease: general principles

General principles for immunosuppressive treatment

Specific glomerular diseases and their management

Minimal change disease

• Management

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

Membranous glomerulonephritis

• Management (Box 10.1)

The effectiveness of the various drug regimens is unclear, and good controlled trials are lacking.

Amyloidosis

• Management

Diabetic nephropathy

This is the most common cause of chronic kidney disease in the developed world. Similar changes occur in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Thickening of the GBM and expansion of the mesangium are associated with glomerular hypertension and glomerular ischaemia, progressing to glomerulosclerosis with nodules (Kimmelstiel–Wilson lesions). Microalbuminuria progresses to overt albuminuria and then progressive renal impairment with or without nephrotic syndrome. Renal biopsy is usually not required unless there are grounds for doubt about the diagnosis (e.g. features suggestive of another cause of glomerulopathy).

• Management (Box 10.1)

Even with all of these measures, relentless progression is common.

Mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (MCGN)

Cryoglobulinaemic renal disease

Recognized associations are as follows:

Lupus nephritis

Post-infectious glomerulonephritis

IgA nephropathy

• Management

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN)

Anti-GBM disease

• Management

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-positive vasculitis

A group of small-vessel vasculitides are characterized by a positive ANCA titre. These include:

These diseases share a common pathology with focal necrotizing lesions that may be limited to the kidney or affect other organs, including the lungs (pulmonary haemorrhage), the dermis (vasculitic rash), and the nose and ear (vasculitic ulceration). Systemic symptoms may predominate (fever, weight loss, malaise) or be absent.

• Management

Thrombotic microangiopathies (p. 231)

Multiple myeloma

Acute or chronic kidney disease may occur, by one or more of the following mechanisms:

Renal Hypertension

Renovascular disease

Renal Stone Disease

Investigations

Management of acute renal stone disease 75 mg by IV infusion

Prophylaxis and prevention

Acute Kidney Injury

The Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative group proposed the RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss, end-stage kidney disease) criteria based on increases in serum creatinine or decreases in urine output (Table 10.3). They characterize three levels of renal dysfunction (R, I, F) and two outcome measures (L, E). These criteria indicate an increasing degree of renal damage and have a predictive value for mortality. The mortality of patients with AKI requiring dialysis is 50%.

| Grade | GFR criteria | UO criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Risk | SCr × 1.5 | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/hour × 6 hours |

| Injury | SCr × 2 | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/hour × 12 hours |

| Failure | SCr × 3 or SCr > 350 µmol/L with an acute rise > 40 µmol/L | UO < 0.3 mL/kg/hour × 24 hours |

| Loss | Persistent AKI > 4 weeks | |

| ESKD | Persistent renal failure > 3 months |

AKI, acute kidney injury; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; SCr, serum creatinine; UO, urine output.

The causes of AKI can be divided into pre-renal, renal and post-renal.

Investigations

Management

• Managing fluid balance

Box 10.2 Indications for dialysis in acute kidney injury

Some Renal Causes of Acute Kidney Injury

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN)

This is the most common cause of AKI, especially in hospital practice. Renal impairment secondary to pre-renal causes (p. 348) will progress to ATN if pre-renal factors are not corrected; patients may be oliguric or non-oliguric.

Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN)

Post-renal AKI

Urinary tract obstruction

Imaging

Management

• Relieving the obstruction

Retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF) (peri-aortitis)

Benign prostatic hypertrophy

• Management

Chronic Kidney Disease

Classification

The US National Kidney Federation Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative classification of CKD has been universally adopted (Table 10.4).

| GFR (mL/min) | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1* | > 90 | Normal kidney function |

| 2* | 60–90 | Mild reduction of kidney function, with other evidence of kidney damage |

| 3 | 30–60 | Moderately reduced kidney function |

| 4 | 15–30 | Severely reduced kidney function |

| 5 | < 15 | End-stage or approaching end-stage kidney disease |

* eGFR of > 60 is normal, unless there is other evidence of kidney disease, e.g. proteinuria, haematuria.

Clinical features

Complications of CKD

• Anaemia

• Renal bone disease

• Management of renal bone disease

| Preparation | Limitations | Side-effects |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium salts, e.g. calcium acetate 500 mg 3 times daily | Calcium load may worsen or precipitate arterial calcification | Hypercalcaemia |

| Sevelamer 2.4–12 g in divided doses chewed with meals 3 times daily | Only used in dialysis patients | GI disturbances |

| Lanthanum 1.5–3 g in divided doses chewed with meals 3 times daily | Only used in dialysis patients | GI disturbances |

| Aluminium hydroxide 475 mg tabs, 1–3 times daily with meals | Aluminium toxicity: avoid except for short-term use |

Management of patients with CKD (Box 10.1)

Preparation for renal replacement therapy

Renal Replacement Therapy

Haemodialysis

Blood is removed from the circulation and passed across a semi-permeable membrane. On the other side of that membrane flows dialysate in a counter-current fashion. Dialysate (Table 10.6) consists of ions at physiological concentrations, allowing homeostasis to be maintained/restored by dialysis treatment by diffusion and equilibration across the membrane. Water (and salt) removal can be controlled by controlling the trans-membrane pressure.

| Haemodialysis | Peritoneal dialysis | |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium | 130–145 | 130–134 |

| Potassium | 0.0–4.0 | 0.0 |

| Calcium | 1.0–1.6 | 1.0–1.75 |

| Magnesium | 0.25–0.85 | 0.25–0.75 |

| Chloride | 99–108 | 95–104 |

| Lactate | 35–40 (or acetate 35–40) | 35–40 |

| Glucose | 0–10 | 77–236 |

| Total osmolality | 356–511 mOsm/kg |

Prescription and adequacy of haemodialysis

Peritoneal dialysis

A peritoneal dialysis catheter is inserted into the peritoneal cavity. This single-lumen tube is usually inserted through the midline and tunnelled subcutaneously to exit on the anterior abdominal wall. Dialysate (Table 10.6) can be infused into the peritoneal cavity using gravity, and after a period of time drained out (again using gravity). Typically the peritoneal cavity can accommodate 1.5–2.5 L of dialysate at any time. Attention to sterile technique is essential.

Adequacy of peritoneal dialysis

Complications of peritoneal dialysis

Renal Transplantation

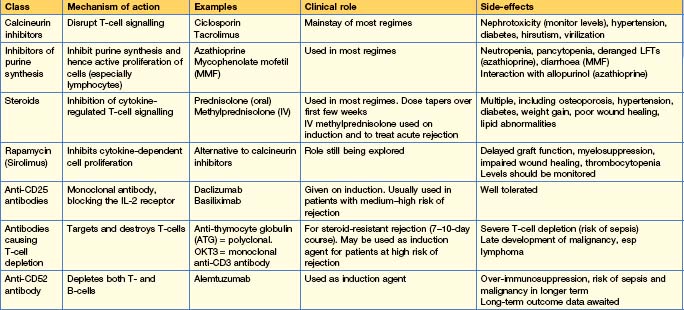

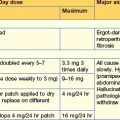

Immunosuppression in renal transplantation

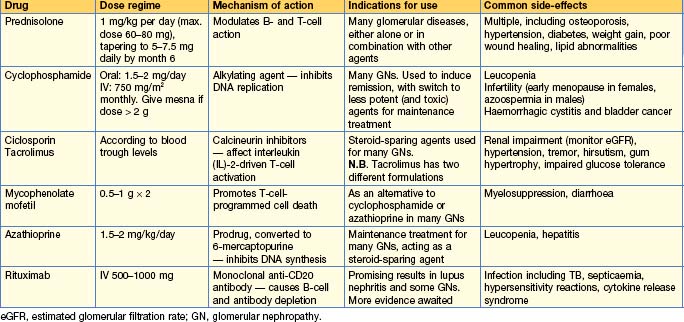

The most commonly used drugs are shown in Table 10.7. Immunosuppression is tailored to the individual, balancing the risks of rejection with those of over-immunosuppression and other side-effects. There are many different combinations of drugs used, varying by patient and by transplant unit, and with trial data continually leading to modifications and refinements in regimes. Monotherapy is unusual — most patients are on 2–3 different immunosuppressive drugs, e.g. ciclosporin (or tacrolimus) + mycophenolate MMF (or azathioprine) + prednisolone. Steroid-free regimes (or early withdrawal of steroids) and calcineurin-free regimes exist and may be suitable for those at highest risk of side-effects from these drugs. In addition, induction agents (e.g. daclizumab, basiliximab, anti-thymocyte globulin) are often given to those at higher risk of rejection at the time of transplantation.