224 Key Issues in Critical Care Nursing

Critical Care Nursing Knowledge and Skill Development

Critical Care Nursing Knowledge and Skill Development

Patricia Benner is said to have revolutionized our understanding of clinical expertise in nursing. In her landmark book, From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice, Benner related the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition to her study of nursing expertise.1 This model was originally developed through a study of skill development among nonclinicians (e.g., chess players and airline pilots). Benner and her colleagues have recently directed their analysis specifically to critical care nursing.2

Some have argued that Benner’s conception of skill acquisition is also relevant to medicine.3 A recent study demonstrated that critical care physicians employ a similar mode of thinking in their practice of diagnostic reasoning.4

Concurrent with this management of a specific case, Benner and her associates further described how an expert nurse also monitors and limits potential hazards in the highly technological critical care environment, fosters teamwork, and initiates preventive and corrective management of systems breakdown.2 These functions are commonly performed without the nurse necessarily being consciously aware of the reasoning that underlies them.

Any strategy that diminishes or fragments the depth of critical care nursing expertise will fundamentally diminish the strength of a critical care service.5 Cho and associates have demonstrated that efforts to reduce nursing staffing levels can significantly increase levels of patient morbidity. A 1-hour decrease of worked nursing hours per patient was associated with a 8.9% increased probability of patients acquiring pneumonia.6

Clinical Topics

Clinical Topics

Pain and Discomfort

It is likely most nurses would list patient pain and discomfort as their most challenging clinical problems. The constancy and proximity of a nurse’s bedside relationship with a patient heightens awareness and attentiveness to unresolved pain and discomfort and can take a deep toll. This is partly due to nursing’s traditional commitment to the promotion of comfort and caring.7,8 Although significant advances have been made over the years in developing effective pharmacologic agents for managing these problems, pain and discomfort commonly persist.9,10

One factor that has limited successful management of these problems is the challenge involved in their evaluation.11 Outside the critical care setting, pain management has benefited from systematic measurement and documentation. Widely accepted pain measures such as the Visual Analogue Scale or numeric rating scales rely on patient self-report, but self-report is typically not accessible in critical care, given patients’ diminished level of consciousness. Thus, observational methods are most appropriate for this population. The Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) has demonstrated reliability and validity for critically ill adults regardless of their level of consciousness.12,13 The CPOT measures four behavioral categories: facial expression, body movements, muscle tension, and compliance with the ventilator for intubated patients or vocalization for extubated patients. Significant experience exists in pediatrics with the utilization of observational pain measures such as the FACES Pain Scale14 and the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale, CHEOPS.15 However, most research has been conducted outside of critical care settings.

In critical care settings, overall “comfort” is increasingly measured with sedation scales.16,17 The Ramsay Scale, likely the most widely used sedation scale in the intensive care unit (ICU), has established some reliability and validity for critically ill adults.18 This is a six-level sedation scale, three levels for when the patient is awake and three levels for when the patient is asleep: 1—anxious, agitated, or restless; 2— cooperative, oriented, or tranquil; 3—responds to commands only; 4—asleep, brisk response to light touch on cheek or loud auditory stimulus; 5—sluggish response; and 6—no response. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses has published a sedation assessment scale for critically ill patients that may be more sensitive to the end goals of sedation.19 It comprises five domains of assessment (consciousness, agitation, anxiety, sleep, patient-ventilator synchrony) as compared to many existing scales that focus only on one or two domains such as consciousness and agitation. In pediatric critical care, the COMFORT Scale has demonstrated impressive merits.20 This consists of eight behavioral and physiologic parameters including alertness, calmness/agitation, respiratory response, physical movement, blood pressure, heart rate, muscle tone, and facial tension. Each parameter is measured along a 5-point rating scale and summed to provide a total score that ranges from 8 to 40. Some work with this tool has indicated that physiologic parameters such as blood pressure and heart rate have weak validity as indicators of discomfort.21 Although these signs are commonly and intuitively associated with patient discomfort, they are also affected by numerous other phenomena within the critical care setting, such as cardiovascular dysfunction.

Delirium is the most common psychiatric diagnosis in critical care; its evaluation and management is therefore a key comfort concern for this population. The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) is a valid and reliable tool developed for bedside assessment of delirium in aduts.22

Sedation in critical care is closely tied to the management of mechanical ventilation discomfort. A problem arising from this sedation-ventilation relation is the complex process of weaning patients from both therapies.23,24 Some research has examined the merits of daily interruption of sedation to permit spontaneous breathing.25,26 The use of a daily “sedation vacation” can help prevent some significant iatrogenic effects of critical care and shorten ICU and hospital stay.

Overall improvements in pharmacologic management of pain and discomfort have contributed to a more recent concern: withdrawal reactions.27 Overly rapid weaning of sedation and analgesia can precipitate a constellation of phenomena such as acute pain, excessive agitation, “ICU psychosis,” as well as withdrawal reactions. Reliable and valid measures for evaluating withdrawal reactions are therefore important in successfully managing this problem. Some strong measurement tools have been documented for the pediatric population.28,29

Although guidelines have been published for recommended rates of weaning, very little empirical research has established the optimal rate for reducing opioid and benzodiazepine infusions, balancing the need to rapidly extubate patients (and therefore minimize ventilation-related morbidities) with the prevention of withdrawal reactions. Some evidence suggests that one optimal weaning rate does not exist.30 It must be tailored to the length of time the patient has been receiving such infusions, whereby 20% daily weaning is optimal for patients receiving continuous infusions for 1 to 3 days, 13% to 20% for 4 to 7 days of infusions, 8% to 13% for 1 to 2 weeks, 8% for 2 to 3 weeks, and 2% to 4% for more than 4 weeks of infusions.30

In their study of critical care nursing judgment in the management of pain, Stannard et al. reported that nurses demonstrated a sophisticated balancing of patients’ analgesic needs against other competing needs.31 A less cumbersome pain and discomfort management process can be established through the use of a sedation protocol or standing orders that “transfer” some decisional autonomy to nurses. A protocol can authorize nurses to modify sedation and analgesia infusion rates and bolus administration according to a prescribed target level of patient comfort.

For example, Alexander and associates reported on a sedation protocol used in pediatric critical care where the COMFORT Scale was used to measure patients’ level of comfort.32 The physician’s prescription specifies a target COMFORT Scale range for the patient, which the nurse can then use as a guideline for modifying the administration of sedation and analgesia. This study reported that patient comfort was managed effectively while facilitating the decision-making process.

Finally, the nursing literature has devoted some attention to the use of nonpharmacologic means for managing pain and discomfort: massage, relaxation exercises, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture, guided imagery, and hypnosis, among others.33 However, these techniques have undergone very little clinical research investigation within critical care. In light of major adverse effects associated with pharmacologic agents, as well as their limitations in fully ensuring patient comfort, these adjunctive measures should be further developed for the critically ill.

Pressure Ulcers

In their study of iatrogenic problems, Cho and associates reported that pressure ulcers had the greatest impact on length of stay (i.e., a 1.84-fold increase).6 Documented prevalence rates vary from 7.1% to 11.1%.34 Jiricka et al. have reported that prevalence rates are even higher among the critically ill.35 This is attributable to the greater likelihood of immobility and reduced skin perfusion.

The principal extrinsic causes of pressure ulcers are pressure, friction, and shear. Therefore, preventive strategies are directed toward minimizing these extrinsic forces. Although over 200 pressure-relieving devices are commercially available, a paucity of controlled clinical trials have examined their efficacy.36

An emerging body of literature is effectively identifying the sites of pressure ulcers and the relative significance of various risk factors. This will help build a base of evidence from which clinical trials can be designed. This literature has led to the development of scoring systems for predicting the risk of pressure ulcers. A highly regarded system is the Braden Scale,37 which has six subscales: mobility, activity, friction and shear, sensory perception, skin moisture, and nutrition; it provides a total score that ranges from 6 to 23 points (high scores indicate less risk). A Braden score of 16 has demonstrated a high degree of sensitivity and specificity in predicting pressure ulcer formation in critically ill adults. This tool has recently been adapted and validated for the pediatric critical care population.38

Whereas pressure ulcers in adults predominantly appear on the lower body (sacrum, ischium, and heels), they are more common on the upper body of children (occiput and ears). This is a result of proportional differences in body weight distribution between these age -groups. A 27% rate of pressure ulcer incidence has been reported in critically ill children, 57% of which were identified on their second day in the ICU.39 Particularly disturbing was that an additional 27 ulcers were identified as caused by medical devices such as oximetry probes, BiPAP masks, and endotracheal tubes.

It is remarkable that wide disparities of preventive measures are currently practiced, including some high-cost pressure-relieving mattresses.36,40 These include some aids that are largely regarded as ineffective, such as synthetic sheepskins.39 Although a substantial amount of evidence has examined this problem outside of critical care, systematic evaluations of management strategies are required to understand their efficacy among the critically ill.

Psychosocial Issues in Critically Ill Patients and Their Families

Patients

Many critically ill patients endure profound psychological trauma, and many others develop delirium or “ICU psychosis.”41,42 One group of patients examined up to 8 weeks after their discharge from an ICU reported “experiences of chaos,” feelings of extreme instability, vulnerability, and fear, as well as prolonged inner tension.43 It was found that even trivial events could trigger changes in their feelings of fear or inner tension. The caring behaviors of nurses provided an important degree of security and comfort. Hupcey reported that the overarching need of critically ill patients is the need to feel safe.44

In an investigation of the experiences of patients through their transfer out of ICU, patients exhibited feelings of significant despondency and apprehension.45 These findings highlight the mandate for greater attentiveness to the needs of these highly vulnerable adults. A number of studies suggest that some of these patients exhibit manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).46–48 More research is needed, as the prevalence of PTSD and the optimum timing and method for assessing PTSD among the critically ill has not yet been determined.49

McKinley and colleagues50 have developed a tool for assessing anxiety in critically ill patients: the Faces Anxiety Scale. This single-item tool requires patients to select one of five drawings of faces. The scale exhibits minimal subject burden, while eliciting self-reports more often than other self-report scales.

Among psychological studies of critically ill children, Rennick et al. have reported that children who were younger, more severely ill, and underwent more invasive procedures demonstrated more medical fears, a lower sense of control over their health, and ongoing posttraumatic stress responses up to 6 months after discharge.47 In a long-term follow-up study of critically ill children, significant dispositional and mental function changes were reported.51 Parental accounts and clinical evaluations suggested that these children were profoundly transformed by their critical illness for variable lengths of time. Papathanassoglou and Patiraki reported similar observations among critically ill adults.52

Families

Many studies of families of the critically ill can be traced to Molter’s examination of family needs.53 Following Molter’s introduction of the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory, several studies systematically investigated the needs of these families. This body of research has demonstrated that families need honest, clear, and timely information, liberal visiting policies, and competent and compassionate care for their family member.54 “Hope” has been described as the most frequently used method of coping,55 which has complex implications for how clinicians portray the patient’s outlook. The latter report also indicated that families identified the provision of information, emotional support, and the competence and manner of the nurse as helpful nursing interventions. A systematic review has examined the impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families.56 Although it is clear pediatric critical illness is stressful for the family, the reported effects on parents, siblings, and marital relations are variable. It is evident that many of these families’ needs go unmet.

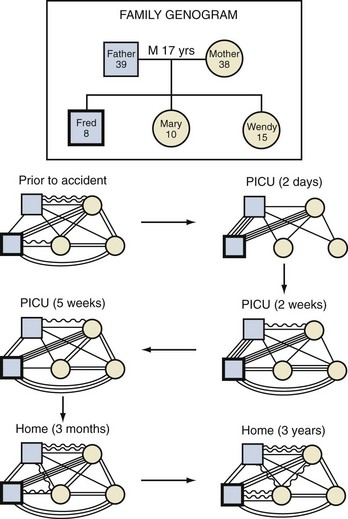

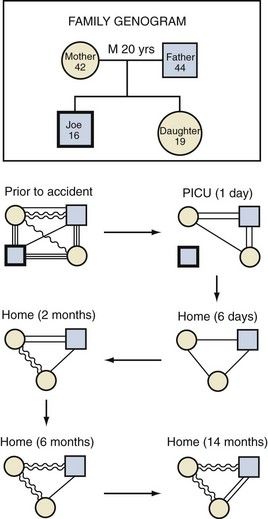

Carnevale51,57 has described a family systems model for understanding the experiences of families of critically ill patients. Drawing on family therapy theory, this model recognizes families as constellations of interrelationships among members, including the critically ill patient. Variable levels of attachments or conflicts that continually change over time characterize these ties (Figures 224-1 and 224-2). Space constraints preclude additional discussion of death and dying in critical care, but some relevant issues will be discussed in the ethics review in the next section.

Figure 224-2 Diagrams demonstrating the profound relational transitions that followed the death of a family member.

Any significant event that affects one member of a family system will necessarily affect the entire family constellation. A common feature that appears to characterize the response of families of critically ill children is a deeply motivated attempt to recapture life as it was before the need for critical care.51 Although it is plausible that families of critically ill adults have similar responses, this requires further study. This work suggests that the quality of the patient’s experience through his/her critical illness is intimately intertwined with the quality of the family’s experience. For example, efforts to preserve family integration—through the rigorous promotion of family presence and participation in the care of the patient—help satisfy numerous family needs while also profoundly comforting the patient’s deepest stresses. Generally, what is good for the family tends to be good for the patient, and vice versa.

Therefore, ICUs should promote the implementation of family support and follow-up programs to help alleviate patient and family distress. Some data have demonstrated that such programs can be highly effective.58

Ethical Dilemmas in Critical Care Nursing

In an anonymous survey of 852 critical care nurses in the United States, Asch reported that 16% stated they had either performed euthanasia or assisted in suicide, following the requests of patients or family members.59 Several informant quotes were provided that suggested these nurses were quite frustrated with the physicians they were working with, whom they described as detached and insensitive to patients’ suffering. The paper implies that these frustrated nurses unilaterally took matters into their own hands to do what they thought was right for the patient. Following the release of this paper and the understandable media attention that followed, many hospital centers turned to their critical care nurses to examine whether such practices were performed within their own institution. Although the practice of euthanasia or assisted suicide was clearly illegal and therefore unacceptable within the study’s jurisdictions, many of the controversies that ensued missed the central phenomenon highlighted by the study: these nurses attempted to report serious problems in their units that placed them in significant ethical binds.

Nurses are autonomous professionals who bear responsibility for patient well-being (albeit within a multidisciplinary team context). Nurses practice according to a professional code of ethics (which may vary somewhat across regions) that requires them to do everything they can to ensure that patient needs are adequately met. Bioethicist Tristram Engelhardt60 observed that:

Critical care nurses frequently find themselves in a moral bind in which they judge that the current medical plan conflicts with their appraisal of the wishes or needs of the patient. This can create moral distress among nurses if they find themselves in a situation where they do not have the power to do what they believe should be done.61

The Manitoba, Canada, government commissioned an inquest into a series of pediatric cardiac deaths in which there was suspicion regarding a surgeon’s competence. The inquest report recognized that the nurses held important insights into the unfolding situation and were inadequately “heard” by their organization.62 The report highlighted that nurses bear a responsibility to ensure patients are protected from harms and risks, and that the organization is responsible for creating mechanisms that can facilitate the inclusion of nurses in clinical and administrative decisions. One such mechanism can include the creation of a nursing ethics committee where nurses can feel free to examine nursing-specific concerns.63

This “in-between” viewpoint of nurses (between the patient and the physician) can help shed new light on a number of ethical dilemmas in critical care and foster new strategies for resolving them. For example, one study examined the controversy over the practice of judging some critical care interventions as “futile” under certain conditions (e.g., cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a patient with a very grave prognosis) and can therefore be unilaterally withheld or withdrawn by the critical care team.64 This study highlighted that such conflicts are rarely related to an intervention’s actual physiologic futility (i.e., whether or not it will achieve its intended purpose) but about fundamental disparities in the beliefs and values of the various persons involved in the conflict. Therefore, ethically sensitive strategies should aim to address these differences through reciprocal discussions and negotiations that seek to reconcile the disparities rather than assert declarations of futility.

Chambers-Evans has illuminated the particular difficulties involved in being a surrogate decision maker (i.e., a family member making decisions for a critically ill patient).65,66 She has proposed a model that promotes shared decision making. This ensures that the surrogate’s intimate understanding of the patient’s wishes and interests are adequately considered while diminishing the surrogate’s moral burden associated with feeling solely responsible for the life and death of their loved one.

Finally, some nurses have examined the impact of family presence during resuscitation.67–68 This work suggests that there is increasing recognition of the merits of family presence, although priorities for further research are outlined. In sum, nursing perspectives on ethical issues in critical care both foster an awareness of the particular moral binds of nurses and illuminate new insights into the multidisciplinary management of prevalent ethical problems.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Over 20 years ago, Knaus and associates demonstrated that the mortality outcomes of a critical care unit are not a function of the level of technology the unit possesses, its university-teaching status, or a closed (versus open) unit.69 Rather, outcomes are strongly associated with the strength of the interdisciplinary collaboration practiced within the unit.

Key Points

Benner P, Hooper-Kyriakidis P, Stannard D. Clinical wisdom and interventions in critical care: a thinking-in-action approach. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1999.

Cho SH, Ketefian S, Barkauskas VH, et al. The effects of nurse staffing on adverse events, morbidity, mortality, and medical costs. Nurs Res. 2003;52:71-79.

Gélinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, et al. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:420-427.

Bergstrom N, Braden BJ, Laguzza A, et al. The Braden Scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nurs Res. 1987;36:205-210.

Austin W, Kelecevic J, Goble E, Mekechuk J. An overview of moral distress and the paediatric intensive care team. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16:57-68.

1 Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

2 Benner P, Hooper-Kyriakidis P, Stannard D. Clinical wisdom and interventions in critical care: a thinking-inaction approach. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1999.

3 Gordon DR. Clinical science and clinical expertise: Changing boundaries between art and science in medicine. In: Lock M, Gordon DR, editors. Biomedicine examined. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1988:257-295.

4 Rashotte J, Carnevale FA. Medical and nursing clinical decision making: a comparative epistemological analysis. Nurs Philos. 2004;5:160-174.

5 Morrison AL, Beckmann U, Durie M, et al. The effects of nursing staff inexperience (NSI) on the occurrence of adverse patient experiences in ICUs. Aust Crit Care. 2001;14:116-121.

6 Cho SH, Ketefian S, Barkauskas VH, et al. The effects of nurse staffing on adverse events, morbidity, mortality, and medical costs. Nurs Res. 2003;52:71-79.

7 Benner P, Wrubel J. The primacy of caring: stress and coping in health and illness. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1989.

8 Watson J. Nursing: Human science and human care. New York: National League for Nursing; 1988.

9 Carroll KC, Atkins PJ, Herold GR, et al. Pain assessment and management in critically ill postoperative and trauma patients: A multisite study. Am J Crit Care. 1999;8:105-117.

10 Puntillo KA. Dimensions of procedural pain and its analgesic management in critically ill surgical patients. Am J Crit Care. 1994;3:116-122.

11 Shannon K, Bucknall T. Pain assessment in critical care: What have we learnt from research? Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2003;19:154-162.

12 Gélinas C, Arbour C. Behavioral and physiologic indicators during a nociceptive procedure in conscious and unconscious mechanically ventilated adults: similar or different? J Crit Care. 2009;24:628.e7-628.e17.

13 Gélinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, et al. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:420-427.

14 Bieri D, Reeve R, Champion GD, et al. The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: Development, initial validation and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain. 1990;41:139-150.

15 McGrath PJ, Johnson G, Goddman JT, et al. CHEOPS: A behavioral scale for rating postoperative pain in children. Adv Pain Res Ther. 1985;9:395-402.

16 De Jonghe B, Cook D, Appere-De-Vecchi C, et al. Using and understanding sedation scoring systems: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(3):275-285.

17 Olson DM, Thoyre SM, Auyong DB. Perspectives on sedation assessment in critical care. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2007;18:380-395.

18 Ramsay MAE, Savege TM, Simpson BRJ, et al. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone. BMJ. 1974;2:656-659.

19 De Jong MM, Burns SM, Campbell ML, et al. Development of the American association of critical-care nurses’ sedation assessment scale for critically ill patients. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(6):531-544.

20 Ambuel B, Hamlett K, Marx C, et al. Assessing distress in pediatric intensive care environments: The COMFORT scale. J Pediatr Psychol. 1992;17:95-109.

21 Carnevale FA, Razack S. An item analysis of the COMFORT Scale in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2002;3:177-180.

22 Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286:2703-2710.

23 Fuchs EM, Von Rueden K. Sedation management in the mechanically ventilated critically ill patient. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2008;19:421-432.

24 Riker RR, Fraser GL. Altering intensive care sedation paradigms to improve patient outcomes. Crit Care Clin. 2009;25:527-538.

25 Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:126-134.

26 Girard TD, Ely EW. Protocol-driven ventilator weaning: reviewing the evidence. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:241-252.

27 Puntillo K, Casella V, Reid M. Opioid and benzodiazepine tolerance and dependence: Application of theory to critical care practice. Heart Lung. 1997;26:317-324.

28 Franck LS, Harris SK, Soetenga DJ, et al. The Withdrawal Assessment Tool-1 (WAT-1): an assessment instrument for monitoring opioid and benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms in pediatric patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:573-580.

29 Ista E, van Dijk M, de Hoog M, et al. Construction of the Sophia Observation Withdrawal Symptoms scale (SOS) for critically ill children. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1075-1081.

30 Ducharme C, Carnevale FA. A prospective study of adverse reactions to the weaning of opioids and benzodiazepines in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2000;1(Suppl):118.

31 Stannard D, Puntillo K, Miaskowski C, et al. Clinical judgment and management of postoperative pain in critical care patients. Am J Crit Care. 1996;5:433-441.

32 Alexander E, Carnevale FA, Razack S. Evaluation of a sedation protocol for intubated critically ill children. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2002;18:292-301.

33 Fontaine DK. Nonpharmacologic management of patient distress during mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Clin. 1994;10:695-708.

34 Amlung SR, Miller WL, Bosley LM. The 1999 National Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey: A benchmarking approach. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14:297-301.

35 Jiricka MK, Ryan P, Carvalho MA, et al. Pressure ulcer risk factors in an ICU population. Am J Crit Care. 1995;4:361-367.

36 Theaker C. Pressure sore prevention in the critically ill: What you don’t know, what you should know and why it’s important. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2003;19:163-168.

37 Bergstrom N, Braden BJ, Laguzza A, et al. The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk. Nurs Res. 1987;36:205-210.

38 Curley MAQ, Razmus IS, Roberts KE, et al. Predicting pressure ulcer risk in pediatric patients: The Braden Q Scale. Nurs Res. 2003;52:22-33.

39 Curley MA, Quigley SM, Lin M. Pressure ulcers in pediatric intensive care: Incidence and associated factors. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2003;3:284-290.

40 Allman RM, Goode PS, Burst N, et al. Pressure ulcers, hospital complications, and disease severity: Impact on hospital costs and length of stay. Adv Wound Care. 1999;12:22-30.

41 Gelling L. Causes of ICU psychosis: The environmental factors. Nurs Crit Care. 1999;4:22-26.

42 Webb JM, Carlton EF, Geehan DM. Delirium in the intensive care unit: Are we helping the patient? Crit Care Nurs Q. 2000;22:47-60.

43 Granberg A, Bergbom Engberg I, Lundberg D. Patients’ experience of being critically ill or severely injured and cared for in an intensive care unit in relation to the ICU syndrome: I. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1998;14:294-307.

44 Hupcey JE. Feeling safe: The psychosocial needs of ICU patients. J Nurs Scholarship. 2000;32:361-367.

45 McKinney AA, Deeny P. Leaving the intensive care unit: A phenomenological study of the patients’ experience. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2002;18:320-331.

46 Jones C, Griffiths RD, Humphris G, et al. Memory, delusions, and the development of acute posttraumatic stress disorder-related symptoms after intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:573-580.

47 Rennick JE, Johnston CC, Dougherty G, et al. Children’s psychological responses after critical illness and exposure to invasive technology. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23:133-144.

48 Schnyder U, Morgeli H, Nigg C, et al. Early psychological reactions to life-threatening injuries. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:86-92.

49 Griffiths J, Fortune G, Barber V, et al. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1506-1518.

50 McKinley S, Coote K, Stein-Parbury J. Development and testing of a Faces Scale for the assessment of anxiety in critically ill patients. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41:73-79.

51 Carnevale FA. “Striving to recapture our previous life”—The experience of families of critically ill children. Off J Can Assoc Crit Care Nurs. 1999;9(4):16-22.

52 Papathanassoglou ED, Patiraki EI. Transformations of self: A phenomenological investigation into the lived experience of survivors of critical illness. Nurs Crit Care. 2003;8:13-21.

53 Molter NC. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients. Heart Lung. 1979;8:332-339.

54 Van Horn E, Tesh A. The effect of critical care hospitalization on family members: Stress and responses. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2000;19:40-49.

55 Koller PA. Family needs and coping strategies during illness crisis. AACN Clin Issues Crit Care Nurs. 1991;2:338-345.

56 Shudy M, de Almeida ML, Ly S, et al. Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: a systematic literature review. Pediatrics. 2006;118(Suppl 3)):S203-S218.

57 Carnevale FA. The injured family. In: Moloney-Harmon PA, Czerwinski SJ, editors. Nursing Care of the Pediatric Trauma Patient. St. Louis: Saunders; 2003:107-117.

58 Curley MAQ. Effects of the nursing mutual participation model of care on parental stress in the pediatric intensive care unit. Heart Lung. 1988;17:682-688.

59 Asch DA. The role of critical care nurses in euthanasia and assisted suicide. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1374-1379.

60 Engelhardt HT. Physicians, patients, health care institutions—and the people in between: nurses. In: Bishop AH, Scudder JR, editors. Caring, curing, coping: nurse, physician, patient relationships. Birmingham, AL: University of Alabama Press; 1985:73.

61 Austin W, Kelecevic J, Goble E, et al. An overview of moral distress and the paediatric intensive care team. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16:57-68.

62 Sinclair M. The report of the Manitoba pediatric cardiac surgery inquest: An inquiry into twelve deaths at the Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre in 1994. Canada: Provincial Court of Manitoba; 2001. Available online at http://www.pediatriccardiacinquest.mb.ca/

63 Bradley K, Collinge J. [A forum on nursing ethics; a necessity in pediatric nursing] French. Infirm Que. 1997;5(2):58-60.

64 Carnevale FA. The utility of futility: The construction of bioethical problems. Nurs Ethics. 1998;5:509-517.

65 Chambers-Evans J. The family as window onto the world of the patient: Revising our approach to involving patients and families in the decision-making process. Can J Nurs Res. 2002;34:15-31.

66 Chambers-Evans J, Carnevale FA. Dawning of awareness: the experience of surrogate decision making at the end of life. J Clin Ethics. 2005;16:28-45.

67 Clark AP, Meyers TA, Eichorn DJ, et al. Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation and invasive procedures: A research-based intervention. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001;13:569-575.

68 Latour JM. Perspectives on parental presence during resuscitation: A literature review. Pediatr Intensive Care Nurs. 2002;3(1):5-8.

69 Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. An evaluation of outcome from intensive care in major medical centers. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:410-418.