Chapter 46 Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is a chronic autoimmune disease that begins before 16 years of age. It is the most common rheumatic disease in children and is a leading cause of short- and long-term disability. It is also a major cause of eye disease leading to blindness. Although its exact etiology is unknown, it is immune-mediated, with abnormal cytokine production in the inflammatory pathway (increased tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6). There are also genetic predispositions, as well as environmental triggers such as infection, trauma, or stress. JRA causes chronic inflammation of the synovium with joint effusion, which can result in eventual erosion and destruction of the articular cartilage. If the process persists long enough, adhesions between the joint surfaces and ankylosis of the joints develop.

The diagnosis is based on the following criteria defined by the American College of Rheumatology:

1. The age at onset must be less than 16 years.

2. Objective evidence of arthritis must be present (defined as swelling or effusion, or presence of two or more of the following: limitation of range of motion, tenderness or pain on motion, and increased heat) in one or more joints.

3. The duration of the disease is 6 weeks or longer.

4. The onset type is defined by the type of disease in the first 6 months:

Common characteristics of JRA include morning stiffness, joint pain, limping gait, fatigue, anorexia, anemia, and weight loss.

INCIDENCE

1. JRA is twice as common in girls.

2. The incidence of JRA varies from 2 to 20 in 100,000 per year. Prevalence is about 1 per 1000 children.

3. Age ranges of peak incidence are 1 to 3 years and 8 to 11 years.

4. Subtype frequencies are systemic, 10%; polyarticular, 30%; and pauciarticular, 60%.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Systemic JRA

1. Systemic JRA is characterized by persistent, intermittent (quotidian) fever: daily or twice-daily temperature elevations to 102.2° F (39° C) or higher, with rapid return to normal temperature between fever spikes. The fever is usually present in the late afternoon to evening. It almost always occurs with the rheumatoid rash.

2. The rheumatoid rash is described as salmon-pink erythematous macules on the trunk and extremities. The rash is migratory and in 5% of cases is reported to be pruritic.

3. Arthritis may not occur until weeks or months after the onset of the symptoms.

4. It affects 10% of all JRA patients, with peak onset from 1 to 5 years of age.

5. The arthritis pattern may be pauciarticular (one to four joints affected) or polyarticular (five or more joints affected). Those children with polyarthritis have a tendency for erosions and a poorer prognosis.

6. Extraarticular symptoms are present, including hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, pericarditis, and pleuritis.

Polyarticular JRA

1. Arthritis is present in five or more joints in the first 6 months of disease.

2. Peak age of onset is between ages 1 and 4 years, and between 6 and 12 years.

3. Systemic manifestations include low-grade fever, fatigue, anorexia, growth failure, and weight loss.

4. Morning stiffness, gelling or stiffness after inactivity, joint pain, and sluggishness with movement are characteristic.

5. Joint involvement is generally symmetric and usually involves the large joints of the knees, the wrists, the elbows, and the ankles. The small joints of the hands and the feet may also be affected.

6. The cervical spine and the temporomandibular joints are often involved.

7. If the temporomandibular joint is involved, impaired biting, shortness of the mandible, and micrognathia may result.

8. Those with onset in late childhood or adolescence who are rheumatoid factor–positive tend to have a more severe disease course than those who are rheumatoid factor–negative.

9. Rheumatoid nodules occur in 5% to 10% of children with JRA, but are most often seen in those with polyarticular disease who are rheumatoid factor–positive. The typical rheumatoid nodule is firm, movable, and nontender. They usually occur below the elbow or at other pressure points.

Pauciarticular JRA

1. Arthritis is present in one to four joints in the first 6 months of disease.

2. Pauciarticular-onset JRA primarily affects girls, aged 2 to 4 years.

3. The joints most commonly affected are the knees and the ankles.

4. The affected joints are swollen and warm, but usually not painful or tender.

5. Uveitis (15% to 20% of cases) is insidious and often asymptomatic.

6. Disease course is variable. After the first 6 months, 5% to 10% develop a polyarticular disease course.

COMPLICATIONS

1. Uveitis is intraocular inflammation of the iris and the ciliary body, found in 15% to 20% of children with pauciarticular-onset JRA, in 5% of those with polyarticular-onset JRA, and rarely in children with systemic-onset JRA. At increased risk for development of uveitis are girls with pauciarticular-onset disease. Those with a positive antinuclear antibody are at even higher risk. The onset is usually insidious and asymptomatic; however, approximately half of children have some symptoms (pain, redness, headache, photophobia, change in vision) later in the disease course. If not diagnosed early, the disease can result in cataracts, glaucoma, visual loss, and blindness. If the disease is detected early, the prognosis is improved. In about half of all patients with uveitis, it occurs before the arthritis is diagnosed, at the time of diagnosis or soon after. In 70% to 80% of children, the uveitis is bilateral.

3. Growth disturbances, including leg length discrepancy and micrognathia

4. Valgus deformity, cervical spine ankylosis

6. Cardiopulmonary complications and other systemic complications

7. Severe anemia and malnutrition

8. Renal, bone marrow, gastrointestinal, and liver toxicity to drugs

9. Macrophage activation syndrome is a rare but severe complication of systemic JRA leading to severe morbidity and sometimes death. The syndrome is characterized by rapid development of fever, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and liver failure with encephalopathy, purpura, bruising, and mucosal bleeding. A bone marrow aspiration showing active phagocytosis of red cells and white cells by macrophages and histiocytes confirms the diagnosis.

LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

There are no laboratory tests that yield the juvenile rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis. Lab testing is more supportive than diagnostic.

1. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level—may be increased with inflammation. These are occasionally helpful in measuring disease activity and monitoring response to antiinflammatory medications. However, these values are often normal in JRA and do not necessarily correlate with response to medications.

2. Rheumatoid factor—present in only 15% of children with JRA (primarily those with polyarticular disease)

3. Antinuclear antibodies—primarily seen in pauciarticular JRA (in 40% of cases); reflect increased risk for uveitis

4. Complete blood count—leukocytosis is common with active disease, and can be very high (30,000 to 50,000/mm3 in those with systemic-onset JRA); polymorphonuclear leukocytes predominate. The platelet count may be high in severe disease activity.

5. Complement levels (C3)—often increased with disease activity, acting as an acute phase protein

6. Immunoglobulin levels—correlate with disease activity

7. Synovial fluid analysis (cell count and culture)—to rule out other conditions, especially infection

8. Urinalysis—mild proteinuria may accompany increased fever, or may be related to medication side effects

9. Imaging studies such as plain film radiography, computed tomography (CT), high-resolution ultrasonography, radionucleotide imaging, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are helpful in diagnosing arthritis and monitoring disease progression. Findings may include soft tissue swelling, epiphyseal overgrowth, marginal erosions, narrowing of cartilaginous space, joint subluxation, and bony fusion. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan measures bone mineral density in order to diagnose osteopenia or osteoporosis.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

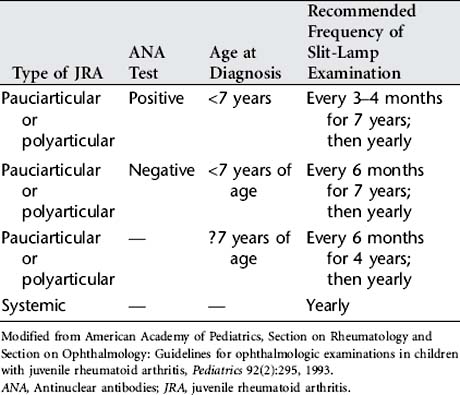

Treatment goals for JRA are to control pain; reduce the inflammatory process; preserve range of motion, and increase muscle strength and function; manage systemic complications; facilitate normal nutrition and growth; promote independence in activities of daily living; and maintain the child or adolescent’s self-esteem and self-image in the face of a chronic illness. Drug therapy is used to reduce inflammation. JRA is treated earlier and more aggressively to decrease disability. Physical and occupational therapy and a regular daily program of exercise are essential to promote mobility and function. Heat is used to relieve joint pain and stiffness. The treatment plan also includes frequent slit-lamp microscopy examinations by an ophthalmologist according to specified guidelines (Table 46-1).

1. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used to control inflammation, fever, and pain. Aspirin and salicylates are no longer used as the first-choice NSAIDs because of the association with Reye’s syndrome during influenza or varicella infection and the availability of other NSAIDs. Naproxen, ibuprofen, tolmetin, piroxicam, indomethacin, meloxicam, and diclofenac are common NSAIDs used in JRA. To be effective antiinflammatories, NSAIDs must be taken on a routine basis. If adequate effectiveness is not achieved after 2 to 3 months, an alternative NSAID can be tried. Many children require a second-line medication in addition to an NSAID to control disease activity.

2. Methotrexate is the initial second-line medication for the treatment of JRA. Given orally once a week in small doses, it has been markedly effective in the treatment of arthritis in children. It is also given subcutaneously once a week for higher dosages or in children with poor absorption or inadequate response.

3. Glucocorticoid drugs: systemic glucocorticoids (daily oral or intravenous pulse steroids) are used for uncontrolled or life-threatening systemic JRA or polyarticular disease that has been unresponsive to other therapies. They are also used as a temporary measure until the second-line drug is effective. Intraarticular steroid injections (triamcinolone hexacetonide) are indicated for the management of pauciarticular JRA that has not responded to NSAIDs, and for the management of polyarticular disease in which one or several joints have not responded to antiinflammatory drugs. These joint injections are generally done under anesthesia or conscious sedation.

4. Biologic response modifiers such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have demonstrated much promise in the treatment of JRA. Etanercept has been approved for pediatric use as a subcutaneous injection given twice per week. It has become standard therapy for JRA that has not responded well to methotrexate. Infliximab, which is given as an infusion, is also being used for JRA treatment. Before starting biologic response modifiers, a negative skin reaction to purified protein derivative (PPD) should be documented. These drugs should not be given while the child has a serious infection.

5. Other biological response modifiers: Anakinra, an IL-1 receptor inhibitor, is used as a once daily subcutaneous injection in systemic-onset JRA. Thalidomide has also been recommended for treatment of systemic-onset JRA.

6. Slower-acting antirheumatic drugs or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs can be added to the medical treatment program for children who have an inadequate response to the NSAID, methotrexate, and a TNF blocker. These include hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, parenteral gold compounds, and penicillamine.

7. Intravenous immunoglobulin is sometimes used in severe, progressive systemic and polyarticular disease.

8. Cytotoxic and immunosuppressive drugs (azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporin) are used occasionally in children with JRA who have life-threatening complications, major steroid toxicity, or severe progressive, erosive disease. Cyclosporin has been found to be beneficial in treatment of the macrophage activation syndrome seen in systemic JRA.

9. Autologous stem cell transplantation is an experimental treatment that is being evaluated in a small number of children. It is very risky and is associated with a high death rate.

NURSING INTERVENTIONS

1. Provide pain relief measures as necessary.

2. Promote joint mobility, maintain strength, and prevent deformity of joints.

3. Collaborate with physical therapist and/or occupational therapist to devise methods that will promote independent functioning.

4. Monitor growth and development pattern.

5. Assist child with intervention strategies for common school problems.

6. Provide education and support to child and family to maximize coping with a chronic and sometimes disabling disease.

Box 46-1 Resources

• www.pedrheumonlinejournal.org. The Pediatric Rheumatology Online Journal is a refereed publication developed for the international pediatric rheumatology community.

• www.goldscout.com. This is the pediatric rheumatology webpage developed by Thomas Lehman, MD (pediatric rheumatologist).

• www.arthritis.org. This is the official website for the Arthritis Foundation. The address for the national office is Arthritis Foundation, 1330 Peachtree Street, Atlanta, GA 30309 (404-872-7100). The American Juvenile Arthritis Organization (AJAO) is a council of the Arthritis Foundation, available online at www.arthritis.org/communities/juvenile_arthritis/about_ajao.asp. The Arthritis Foundation publishes Kids Get Arthritis Too, which includes articles on current topics, research reviews, “Ask the Experts” and “Kids Ask Kids” question sections, professional and patient interviews, and news. It can be ordered online or by phone 1-800-933-0032.

Discharge Planning and Home Care

CLIENT OUTCOMES

1. Child will exhibit no signs or symptoms of discomfort and will be able to move with minimal discomfort.

2. Child will be able to perform activities of daily living and participate in age-appropriate activities with minimal fatigue.

3. Child and family will demonstrate understanding of home treatment plan, including medications and home exercise program.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Rheumatology and Section on Ophthalmology. Guidelines for ophthalmologic examinations in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 1993;92(2):295.

Calmak A, Nalan B. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: physical therapy and rehabilitation. South Med J. 2005;98(2):212.

Cassidy JT, et al. Textbook of pediatric rheumatology, ed 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005.

Feldman DE, et al. Factors associated with the use of complementary and alternative medicine in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(4):527.

Lehman TJA. It’s not just growing pains: A guide to childhood muscle, bone and joint pain, rheumatic diseases, and the latest treatments. Oxford: Oxford Press, 2004.

Mason TG, Reed AM. Update in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(5):796.

Miller-Hoover S. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: why do I have to hurt so much? J Infusion Nurs. 2005;28(6):385.