27 Juvenile Dermatomyositis

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous Features

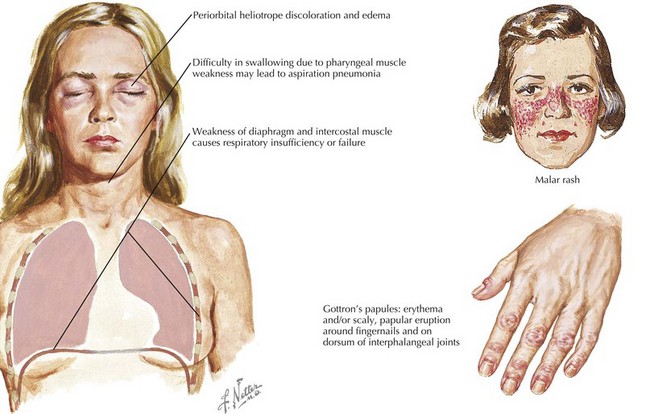

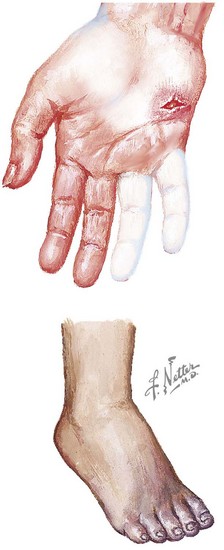

Dermatomyositis has several classic cutaneous findings (Figure 27-1). Gottron’s papules are erythematous, raised, scaling plaques on the dorsal surface of the knuckles, elbows, and knees that are present in more than 90% of children at the time of diagnosis. Gottron’s papules are frequently confused with severe eczema if JDMS is not suspected. The classic heliotrope rash is a violaceous discoloration of the eyelids with associated eyelid edema; this is present in approximately 80% of children at diagnosis. About 40% of children also have a prominent erythematous malar rash. This rash can be ulcerative, cross the nasolabial folds, and extend onto the forehead. Raynaud’s phenomenon (Figure 27-2) and associated nailfold capillary changes are seen in up to 80% of patients. Nailfold changes are characterized by proximal nailfold erythema, capillary dilatation, tortuosity, or dropout. The measured density of capillaries per millimeter may be a useful tool for monitoring clinical activity. Skin ulcerations reflect significant vasculopathy of the skin and may be a sign of internal organ vasculopathy. Ulcerative skin lesions are associated with more severe disease and worse prognosis.

Musculoskeletal Features

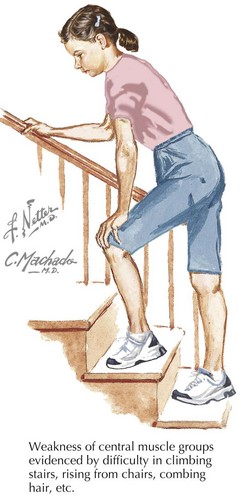

Classic JDMS is manifested by symmetric, proximal muscle weakness especially in the neck, hip flexors, and abdominal wall (Figure 27-3). Targeted muscle testing is necessary because children are often able to compensate well for their weaknesses. Children may have functional limitations at the time of presentation secondary to muscle involvement. For example, affected children may report problems with brushing or washing their hair, climbing stairs, and standing from a seated position (Gower’s sign). Dysphonia, difficulty swallowing, dysphagia, and reflux of food into the nasopharynx may be present due to weakness of the palate, cricopharyngeal muscles, and upper esophagus. Rarely, the myocardium can be involved. Joint contractures may be present as a result of muscle shortening. Muscle tenderness may also be a prominent feature.

Brown VE, Pilkington CA, Feldman BM, Davidson JE. An international consensus survey of the diagnostic criteria for juvenile dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45(8):990-993.

Feldman BM, Rider LG, Reed AM, Pachman LM. Juvenile dermatomyositis and other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies of childhood. Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2201-2212.

Ramanan AV, Feldman BM. Clinical features and outcomes of juvenile dermatomyositis and other childhood onset myositis syndromes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2002;28(4):833-857.