Jaundice

Diagnostic Approach

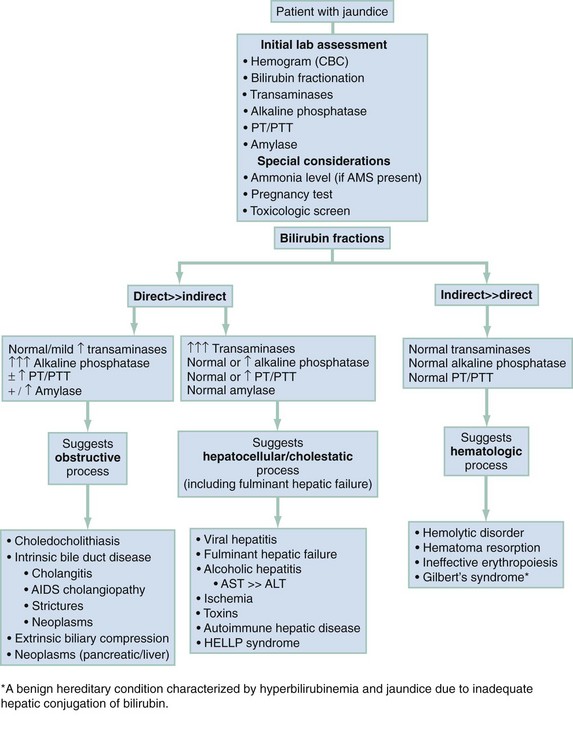

The three major diagnostic categories to consider are liver injury or dysfunction (cholestasis), biliary obstructive disorders, and disorders of hemolysis. Figure 28-1 outlines a laboratory-based approach to differentiating among these three categories.

Pivotal Findings

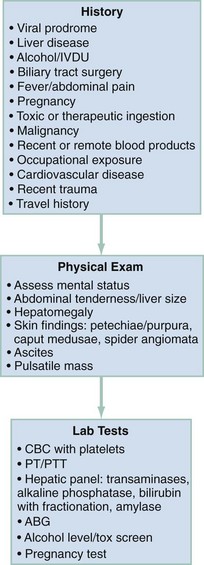

The pivotal findings related to history, physical examination, and ancillary testing are listed in Figure 28-2.

Signs

Pertinent physical examination findings are summarized in Figure 28-2. Examination of the skin and the abdomen is particularly helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

Neurologic examination of the jaundiced patient may show depressed mental status, indicating hepatic encephalopathy or cerebral dysfunction caused by sepsis. Asterixis is a specific finding of hepatic encephalopathy. Table 28-1 addresses the clinical stages of hepatic encephalopathy.

Table 28-1

Clinical Stages of Hepatic Encephalopathy

| CLINICAL STAGE | INTELLECTUAL FUNCTION | NEUROMUSCULAR FUNCTION |

| Subclinical | Normal examination findings, but work or driving may be impaired | Subtle changes in psychometric testing |

| Stage 1 | Impaired attention, irritability, depression, or personality changes | Tremor, incoordination, apraxia |

| Stage 2 | Drowsiness, behavioral changes, poor memory, disturbed sleep | Asterixis, slowed or slurred speech, ataxia |

| Stage 3 | Confusion, disorientation, somnolence, amnesia | Hypoactive reflexes, nystagmus, clonus, muscular rigidity |

| Stage 4 | Stupor and coma | Dilated pupils and decerebrate posturing; oculocephalic reflex |

From Fitz G: Systemic complications of liver disease. In Feldman M, Sleisenger M, eds: Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998.

Laboratory Tests

Figure 28-2 lists the laboratory tests that are helpful in the evaluation of a patient with jaundice. Serum γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) rises in parallel with alkaline phosphatase (AP) in the setting of liver disease.1 Although AP also can be elevated in diseases affecting bone or placenta, the concomitant increase in serum GGT or 5′-nucleotidase confirms a hepatic source. A reticulocyte count and evaluation of the peripheral blood smear may identify hemolysis. In cases of unexplained hepatocellular injury, a quantitative acetaminophen level may be helpful. Bedside stool guaiac testing assesses for the presence of gastrointestinal bleeding. Both glucose and ammonia metabolism can be altered in the presence of hepatocellular injury, and patients with altered mental status should have glucose and ammonia levels determined. The degree of elevation in serum ammonia does not correlate directly with the level of hepatic encephalopathy. Ascitic fluid should be analyzed in patients with new-onset ascites and in those with established ascites but new complaints of fever, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, hypotension, or renal failure. Cell count and differential, albumin, and total protein concentration are sufficient initial screening tests. In the setting of suspected bacterial peritonitis, fluid culture is also necessary; Gram stain is rarely helpful. Two sets of blood cultures should be performed for patients with fever and jaundice. If there is evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding with hemodynamic instability or severe anemia, a type and crossmatch should be performed by the laboratory.

Imaging

Although not always necessary, abdominal imaging can help narrow the differential diagnosis of jaundice, especially in patients for whom biliary obstruction is a concern. The primary role of imaging is in the characterization of obstructive biliary disease. The first choice of study remains somewhat controversial. Ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT) are available in most EDs and are reasonably sensitive in diagnosing obstruction. The choice of imaging procedure depends on the pretest probability that there is biliary obstruction and that the obstruction is malignant. For patients with painless, progressive jaundice and without suspicion of hepatocellular injury (e.g., hepatitis, alcoholism), malignant obstruction has a high pretest probability, so CT is the preferred method owing to its improved sensitivity in locating the site of the obstruction, determining resectability, and assessing for disseminated disease. Patients with a high likelihood of biliary disease and benign obstruction are best screened with US. Ultrasonography is less expensive and less invasive than CT but has a lower sensitivity in identifying common bile duct stones.2,3 US with Doppler flow can detect obstruction in the hepatic, portal, and splenic veins. Sonographic features of cholecystitis are discussed in Chapter 90. In patients with low or intermediate clinical likelihood of mechanical obstruction, US is the preferred modality to evaluate whether or not biliary obstruction is present. CT is preferred if the entire abdomen needs to be evaluated.

Diagnostic Algorithm

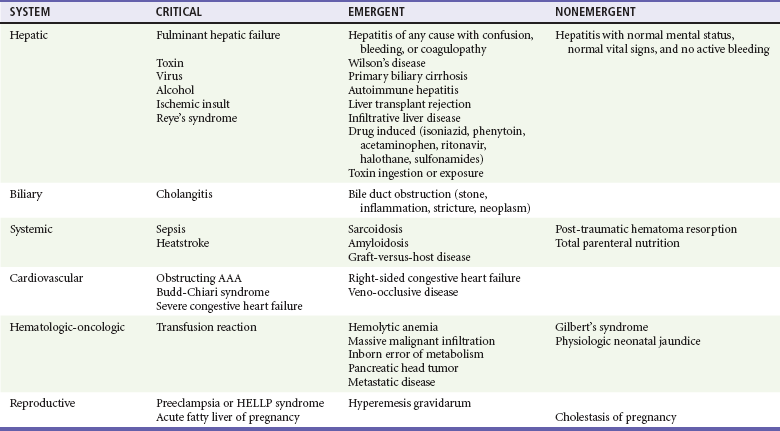

The differential considerations for jaundice are broad; there are critical and emergent causes that should be ruled in or out in the ED. Table 28-2 lists these conditions by organ system. Patients are considered in a critical state if they have jaundice and any of the following: altered level of consciousness, hypotension, fever with abdominal pain, or active bleeding.

Table 28-2

Jaundice: Differential Diagnosis of Critical and Emergent Diagnoses

AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; HELLP, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets.

Further characterization of the cause of jaundice involves analysis of the laboratory studies (Fig. 28-1). Indirect bilirubinemia points to a hematologic cause, whereas direct bilirubinemia indicates hepatobiliary pathology. Elevated direct bilirubin with transaminase elevation is indicative of hepatocellular inflammation or necrosis. Quantitative acetaminophen level, hepatitis serologies, and prothrombin time (PT) should be assessed. Prolongation of PT indicates significant hepatocellular dysfunction. Elevated AP with elevated direct bilirubin indicates extrinsic biliary obstruction. Patients with biliary obstruction require CT or US in the ED to determine the cause and site of the obstruction.

The identification of critical or emergent causes of jaundice requires the clinician to identify patterns in the patient’s signs, symptoms, and ancillary testing. For instance, patients with a triad of jaundice, encephalopathy, and coagulopathy (international normalized ratio [INR] >1.5) have acute hepatic failure.4 Fever, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice can indicate biliary obstruction with infection (e.g., cholangitis, cholecystitis, or hepatitis). Ascites with abdominal tenderness raises suspicion for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). Rapid onset of hepatomegaly and ascites can point to portal vein thrombosis (Budd-Chiari syndrome).

Empirical Management

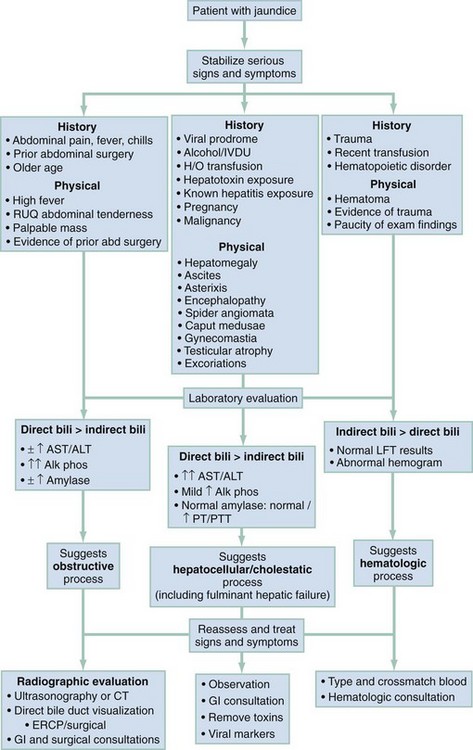

General supportive therapies and specific therapies depend on the presumptive cause of the jaundice (Fig. 28-3). If coagulopathy is known or suspected, compressible sites and ultrasound guidance should be used for central venous access. Coagulopathy in the context of acute hemorrhage should be corrected with fresh frozen plasma and blood volume repletion accomplished with packed red blood cells.

Patients with jaundice and transaminases out of proportion to elevation of AP have a hepatocellular injury pattern. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy is described in Chapter 90. Patients with fulminant hepatic failure should be admitted to the intensive care unit or transferred to a hospital with expertise in severe liver disease, depending on the severity of the illness. Acetaminophen toxicity and indications for N-acetylcysteine therapy are discussed in Chapter 148.

Fever, abdominal pain, and obstructive jaundice suggest ascending cholangitis. Antibiotic recommendations for ascending cholangitis are in Chapter 90. In addition to antibiotics, patients should be resuscitated with intravenous fluids as necessary and have any metabolic derangements corrected. Because biliary excretion of most antibiotics is compromised in the setting of obstruction, all patients will require biliary drainage.5 This generally should be done urgently but may be deferred 24 to 48 hours in stable patients.6 Drainage can be accomplished by endoscopic, percutaneous, or open surgical approaches. Prompt consultation with general surgery or gastroenterology is necessary to determine which approach and timing are appropriate.

Patients with extrahepatic obstructive jaundice without cholangitis should also be admitted for drainage. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is therapeutic for benign obstructions such as gallstones or strictures. Patients with obstructive jaundice caused by malignancy also benefit from biliary decompression, whether operative or endoscopic. Malignancy with jaundice heralds more advanced disease and increased morbidity and mortality.7,8

In general, patients with uncomplicated cholecystitis should receive intravenous fluids in the ED, parenteral analgesics, and antiemetics as needed and should be hospitalized. Antibiotic therapy for acute cholecystitis is discussed in Chapter 90. These patients should undergo emergent imaging and consultation with a surgeon or gastroenterologist.

Patients with confirmed or suspected choledocholithiasis, stones in the common bile duct, require admission for possible ERCP or cholecystectomy.9–11 Neither CT nor US is 100% sensitive in identifying a common bile duct stone, but they are reasonably sensitive in identifying a dilated common bile duct, which is highly suggestive of obstruction.

In immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, the decision to transfuse should be based on the patient’s ability to oxygenate and the ability to institute alternative treatments. An urgent hematology consultation is recommended (see Chapter 121) In the case of drug-induced hemolytic anemia, the mainstay of treatment involves removal of the offending agent. For patients with glucose-6-phosphate deficiency, blood transfusions are rarely indicated, and the focus of management should be on maintaining urine output to prevent renal failure. Patients with hemoglobinopathies rarely require transfusion therapy unless they have severe anemia without evidence of reticulocytosis. Fluids, oxygen, and analgesics can be given for an acute crisis.

Special Populations

Hyperemesis gravidarum usually manifests in the first trimester. The exact mechanism for jaundice is unknown but is likely related to malnutrition and impaired excretion of bilirubin. The liver panel can be abnormal in up to 50% of cases. This includes transaminases elevated up to 20 times the upper limit of normal and mild jaundice.12 ED treatment is unchanged in these cases: hydration and antiemetics. Liver enzymes will normalize with the resolution of vomiting; patients with hyperemesis and jaundice may require admission for intravenous hydration.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is an idiopathic cause of jaundice that occurs in the second or third trimester. It manifests with pruritus mainly in the trunk, extremities, and palms and soles, followed by jaundice after 1 to 4 weeks. Other features of obstructive jaundice such as acholic stools and dark urine may be present. Laboratory analysis reveals a cholestatic picture. These patients are at increased risk for preterm delivery and intrauterine fetal demise and should therefore be managed in conjunction with the obstetric team or transferred to a center capable of caring for premature neonates. Specific treatments include ursodeoxycholic acid or cholestyramine for pruritus and vitamin K.13,14 These treatments should be initiated in conjunction with obstetric and gastroenterologic specialists.

References

1. Lewis, JR, Mohanty, SR. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A review and update. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:560.

2. Sugiyama, M, Atomi, Y. Endoscopic ultrasonography for diagnosing choledocholithiasis: A prospective comparative study with ultrasonography and computed tomography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:143.

3. Williams, EJ, et al. Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2008;57:1004.

4. Bernal, W, Auzinger, G, Dhawan, A, Wendon, J. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2010;376:190.

5. Tanaka, A, et al. Antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:59.

6. Wada, K, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:52.

7. Hawkins, WG, et al. Jaundice predicts advanced disease and early mortality in patients with gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:310.

8. Qin, L, Tang, Z. Hepatocellular carcinoma with obstructive jaundice: Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:385.

9. NIH state-of-the-science statement on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for diagnosis and therapy. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002;19:1.

10. Eisen, GM, et al. An annotated algorithm of the evaluation of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:864.

11. Adler, DG, et al. ASGE guideline: The role of ERCP in diseases of the biliary tract and pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:1.

12. Hay, JE. Liver disease in pregnancy. Hepatology. 2008;47:1067.

13. Kondrackiene, J, Beuers, U, Kupcinskas, L. Efficacy and safety of ursodeoxycholic acid versus cholestyramine in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:894.

14. Binder, T, Salaj, P, Zima, T, Vitek, L. Randomized prospective comparative study of ursodeoxycholic acid and 5-adenosyl-l-methioninie in the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2006;34:383.