Chapter contents

4.1 Pulse diagnosis and the need for clear and unambiguous terminology 34

4.2 Pulse diagnosis, subjectivity and the need for reliable assessment methods 37

4.3 Pulse in changing contexts 38

4.4 The normal pulse 38

4.5 Reliability and validity of the pulse diagnosis process 39

4.6 Radial pulse palpation method 42

In their guidelines for providers of CM education, the World Health Organization (WHO 1999) regarded pulse diagnosis as a core component of the CM diagnostic framework and integral to the curriculum of quality degree programs in acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine. This view is similarly reflected in curriculum guidelines by accreditation and regulation authorities in various countries (BAC 2000, BMA 2000, NASC 2001). These recommendations are largely founded on the premise that pulse assessment is a clinically reliable diagnostic technique. The antiquity of the use of the technique and historical roots are seen as proof of this; if a technique has been in use for so long, then who is to question the practice of pulse diagnosis? Unfortunately, a ready acceptance of what is written in the classics and contemporary texts, combined with the diversity of CM practices, means the pedagogical framework for using pulse diagnostically is readily compromised, so questioning its reliability for this task (Birch 1998, Hammer 2001, King et al 2002, Wiseman & Ye 1999).

At the core of this problem is the actual nature of pulse diagnosis: it is dependent first and foremost on touch. Consequently, the literature and descriptions of the pulse qualities are enshrouded by tactile imagery constructed from a range of literary devices including analogies, similes and metaphors. For example, Wang Shu-he describes the Tight pulse (Jiu/Jing Mai) as being ‘an inflexible pulse like a tensely drawn rope’ (1997: p. 3). At times, writing involved prose as a learning aid. Notably, Li Shi-Zhen’s Bin Hue Mai Xue is written entirely in rhyming format. Yet it is this very use of descriptive imagery that makes pulse diagnosis a doubly difficult technique to apply in a clinical context. Not only is pulse diagnosis dependent on an individual’s perception of touch, but there are no clear and unambiguous guidelines for interpreting these literary images in a practical sense.

With these factors in mind, a reliance on the practitioner’s skills to discriminate between pulses means pulse diagnosis is often regarded as highly subjective. When the pulse diagnosis process is viewed objectively, the lack of sound scientific evidence to support it can be seen as contributing to its questionable validity, if not complicit in perpetuating the aura of mystification often associated with the technique. It is for this very reason that the pulse procedures and terminology used to assess the pulse need to be explicit and detailed enough to ensure that the diagnosis is done correctly. This is termed reliability . How this is achieved, and the factors that affect it, is the central theme of this chapter.

4.1. Pulse diagnosis and the need for clear and unambiguous terminology

Formulating terminology to describe the different pulse types only happened after implementation of pulse in the CM diagnosis process itself (Wiseman and Ye 1999). Originally, pulses were defined descriptively, often using metaphors with particular relevance to everyday life at the time of their development. For example:

When man is sick the pulse of the liver moves more fully, and it is large and long and slightly tense, felt on both light and heavy pressure; but it is also slippery like the sound of many long bamboo rods strung together, then one can speak of a sick liver.

At the point of death the pulse of the liver moves with increased speed and strength, like a new long bow of a musical instrument — and then one can speak of the death of the liver.

When man is tranquil and healthy the pulse of the spleen flows softly, coming together and falling apart like a chicken treading the earth — and then one can speak of a healthy spleen

Yet, despite recognition of the need for more detailed and informative definitions of pulse qualities as undertaken in Mai Jing, the old descriptive terms remained in subsequent writings. For example, in his classic text on pulse diagnosis, Li Shi-zhen describes the Rough (choppy) pulse (Sè mài) with descriptive terms in addition to more informative details from the Mai Jing:

Fine and slow, going and coming difficult, short and scattered.

Possibly one stop and again comes [description from the Mai Jing].

Uneven, not regular [description from the Su Wen].

Like a light knife scraping bamboo [description from the Mai Jue (Pulse Knacks)].

Like rain wetting sand.

Like a diseased silkworm eating a leaf.

Wiseman and Ye (1999) note interpreting pulse qualities is not helped by complications arising from authors over the centuries attempting to expand and further define the pulse types listed in older CM texts and adding their own interpretations while doing so. A further complicating factor with the use of pulse terminology derived from a different cultural context, and indeed, a temporal context as well, is that it is difficult to determine the exact definition and context of the original author’s use of a pulse word or term. Agdal (2005) notes the ‘Language is not a neutral tool describing realities but is embedded with cultural meaning; it is a formative principle which constitutes objects as much as it describes them’ (p. S-68). According to Manaka, Itaya and Birch (1995) this problem is further accentuated when authors do not reference the sources from which they obtained the pulse terminology used, so negating the benefits of a standard system of terminology.

Confusion also arises when terminology is used in a descriptive manner but also to identify specific CM pulse qualities. The Replete pulse is a good example of this dichotomy. The term ‘replete’ is often used in the CM literature to convey the idea of excess, and thus is used as a general descriptor of any pulse that hits the finger with considerable strength on palpation. However, the term is also used to name one of the specific CM pulse types, the Replete pulse (Shí mài), traditionally meaning a pulse that ‘arrives dynamically, it is hard and full, and its movement is large and long. With light touch it remains; with heavy pressure it has force. Its arrival and departure are both exuberant, and it can be perceived at all three levels’ (Deng 1999: p. 125). Further adding to this confusion is the existence of a number of different definitions for the same stated pulse quality, while there may be differently named pulse qualities with the same pulse definition (see TABLE 4.1 and TABLE 4.2).

| Author and source | Skipping pulse (Cù mài) | Rough pulse (Sè mài) | Stirred pulse (Dòng mài) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung & Belluomini (trans) (1982) | Accelerated | Difficult | Agitated |

| Deng (1999) | Skipping | Rough | Stirred |

| Flaws (1997) | Skipping, rapidly, irregularly interrupted | Choppy | Stirring |

| Kaptchuk (2000) | Hurried | Choppy | Spinning Bean |

| Li (Huynh, trans) (1981) | Hasty | Choppy | Moving |

| Lu (1996) | Running | Choppy | Tremulous |

| Maciocia (2004) | Hurried | Choppy | Moving |

| O’Connor & Bensky (trans and ed) (1981) | Hasty | Rough | Not mentioned |

| Porkert (1995) | Agitated | Grating | Mobile |

| Morant (1994) | Accelerated | Hesitant Astringent Rough | Turbulent |

| Wiseman & Ellis (1996) | Skipping Interrupted | Uneven | Stirred |

| Author and source | Definition | Page no. |

|---|---|---|

| Deng (1999) | A replete pulse …arrives dynamically, it is hard and full, and its movement is large and long. With light touch it remains; with heavy pressure it has force. Its arrival and departure are both exuberant, and it can be perceived at all three levels | 125 |

| Guanzhou Chinese Medicine College (1991) | Felt at Cun, Guan and Chi forceful, long and large, on both light and heavy pressure | 18 |

| Li (Huynh, trans) (1981) | Sinking, firmer than the firm pulse, and has a strong beat | 15 |

| When a pulse is felt both superficially and deeply, and has big, long, wiry, strong beats | 73 | |

| Kaptchuk T (2000) | Is big and also strong, pounding hard against the fingers at all three depths | 199 |

| Maciocia (2004) | The Full pulse feels hard, full and rather long; it is felt easily at all levels and it has a springy quality resistant to finger pressure” Also notes the term as a description of a ‘broad range of full pulses…’ | 475 |

| Porkert (1995) | Strong pulse manifesting on at least two levels. Still, the pulse shows its greatest strength and deployment on one particular level, “its specific level’ | 38 |

| Wiseman & Ellis (1996) | Similar to the forceful except it is forceful on both rising and falling | 120 |

Although the traditional pulse qualities have been named for the distinct set of features or characteristics that manifest in the pulse, the names of these specific pulse qualities are sometimes used as general descriptive terms. This arises because the changes in the pulse characteristics cluster in such a way that when a pulse quality ‘appears’ to occur as described in the literature, it may be further complicated by an additional change in another pulse characteristic, and so does not satisfactorily fit the usual description of a particular CM pulse. For example, Maciocia (2004: p. 485) describes a possible formation of a Stringlike (Wiry) (xián mài) and Slippery pulse (Huà mài) occurring with Full Liver pattern and Phlegm, which appears quite contradictory. That is, the Stringlike (Wiry) pulse is defined by the tension in the arterial wall which constrains the arterial contour from manifesting, whereas the Slippery pulse is defined by the arterial contour deforming the arterial wall, which is quite distinctly rounded as it moves under the fingers, and it is the relative lack of arterial tension which allows the pulse wave to form in this way. (There are additional changes in other pulse characteristics that further differentiate the two pulses.) So the question is, why have these two distinctly different terms been used in this way?

The answer is that they have been used in this way because the focus has been on the most apparent or distinctive change occurring in the pulse, rather than on all the information available. By focusing on the apparent changes, the increased arterial tension has been termed the Stringlike (Wiry) pulse. Yet, the classical definition of the Stringlike (Wiry) pulse notes this pulse without a distinct contour, and so by definition the pulse described by Maciocia is not the Stringlike (Wiry) pulse. Similarly, the pulse described is not the Slippery pulse either, despite the presence of Phlegm.

Yet in undertaking the process of pulse diagnosis it is hard for the practitioner not to think of the terminology of the traditional pulse qualities, if only because they have dominated any discourse of pulse diagnosis in Chinese medicine for so many years. However, it soon becomes apparent that there are limitations to the use of the pulse names when used in this way, as evidenced in the example above.

The pulse diagnosis process is further complicated when the traditional pulse names are used to discretely classify the pulse when this is not warranted (that is, when the pulse is categorised or termed as one of the traditional CM pulse qualities but not all aspects or characteristics of its presentation actually fit the traditional definition). In doing so, the other pulse characteristic changes, which do not match the traditional description of the pulse being felt, are excluded. Such an approach means all available clues about the pathogenesis are not considered in diagnoses, and so a practitioner may underestimate or overestimate the pathology against incorrectly ‘recognised’ pulse qualities rather than using all the information that is available. The obvious problem with this is that the lost pulse information may signal the difference between treatment that aims to tonify against one that aims to disperse.

4.1.1. Practical implications of confusion in CM pedagogy

The ultimate outcome of this confusion is great variance in terminology between CM texts affecting the practical application of pulse diagnosis. This includes the application of pulse diagnosis in:

• Treatment planning within clinical practice

• Educational purposes and pulse learning

• Research investigations involving traditional methods of diagnosis.

4.1.1.1. Pulse pedagogy and treatment planning

The absence of standardised pulse terminology has implications for the use of pulse diagnosis in clinical practice, where the role of pulse is thought to have various applications in diagnosis, in treatment formulation and as an immediate indicator of the effectiveness of the treatment (Birch & Felt 1999). When used for these purposes, it is vital that the pulse information is reliable, ensuring that the patient receives the correct diagnosis and so appropriate treatment. This is particularly important when using herbal medicine, as an incorrect diagnosis and hence an incorrect herbal prescription may result in a worsening of the condition. Similarly in acupuncture, there are some systems that rely on pulse assessment as the primary means of diagnosis and so treatment is dependent on a reliable and accurate assessment.

4.1.1.2. Pulse pedagogy and learning

In Asia and elsewhere Birch and Felt (1999) note that there has been a shift away from clinically based pulse teaching to a model that emphasises intellectual or theoretically based knowledge. As a result, intensive clinically based training in pulse diagnosis has fallen out of common use. The theoretical approach is commonly applied in other areas of CM education, and this pedagogical approach is usually based on the premise of a standardised and workable theoretical data set such as that used in Eight Principles differential diagnosis (Ba Gang) or Five Phases (Wu Xing). Such a standardised theoretical approach is often in contrast to the theoretical information on pulse diagnosis, with its characteristic ambiguous descriptive terms which lack clarity.

Consequently, Birch & Felt (1999: p. 235) proposed that the pulse literature was intended as a supportive adjunct to practice-based teaching, and so explains its apparent failings when used as the only form of teaching. Accordingly, they claimed, it was never meant to be the primary means of imparting knowledge in this area. Birch & Felt based their claims on historical texts that documented the traditional teaching methods of pulse diagnosis. The repetitive practice of pulse palpation under a teacher’s guidance in clinic was once the mainstay of education in this area.

Yet even this explanation of the failings of the pulse pedagogy warrants questioning. For example, even as far back as the second century ce, where traditional master—apprentive teaching methods for learning pulse diagnosis were used, Wang Shu-he (author of the Mai Jing) wrote of the difficulty in distinguishing between pulse qualities, even when having memorised the definitions. He used an example in which the Bowstring, Tight, Floating and Scallion Stalk pulses could be seen to share some common characteristics. This, he observed, made these pulses easy to mistake for one another, even with the use of a standard pulse terminology:

The mechanisms of the pulse are fine and subtle, and the pulse images are difficult to differentiate. The bowstring and the tight, the floating and the scallion-stalk confusingly resemble one another. They may be readily distinct at heart (that is, their verbal definition may have been memorized), but it is difficult for the fingers to distinguish them. If a deep pulse is taken as a hidden one, the formula and treatment will never be in the right line. If a moderate pulse is taken as a slow one, crisis may crop up instantly. In addition, there are cases where several different kinds of pulse images appear all at the once or several different categories of disease may exhibit the same type of pulse

Other CM authors argue that pulse taking should not be difficult to learn (Porkert 1995, Flaws 1997), stressing the importance of the theories and of learning the standard textbook definition of each pulse quality (King 2001: p. 37). However, it can be strongly argued that it is precisely the lack of clarity of the standard definitions that cause problems. Wiseman and Ye (1999) note a lack of precision and non-standardised definitions arise when authors and practitioners have failed to identify exactly what they mean when stating or describing pulse characteristics (Wiseman & Ye 1999).

4.1.1.3. Pulse pedagogy and research

In research, ideally, an appropriate study method requires detailed documentation of all facets of the design process, detailing how information was collected, interpreted and decisions made using CM methods of diagnosis, leading to the development of a treatment protocol. Therefore a clear and unambiguous terminology is required here as well. In addition, the careful detailing of both treatment and diagnostic processes should be included in clinical trials (Birch 1997), not only to enable replication of the studies but also to provide clinically relevant information for the CM profession.

A failure to standardise pulse terminology and descriptions hinders the evaluation of traditional-based systems of CM, where the role of pulse is given equal weighting with other assessment approaches. For example, a holistic perspective and a method of treatment tailored to the individual are integral components of the traditional approach to CM. This involves the systematic gathering and collating of patient data to construct a diagnosis and subsequent treatment protocol. With a treatment based directly on the diagnostic assessment, it is vital that this initial process is both objective and reliable. As Flaws notes: ‘In TCM, a correct pattern discrimination is vitally important. It is the guide and foundation to successful, individualised treatment’ (Flaws 1997: p. 3).

4.2. Pulse diagnosis, subjectivity and the need for reliable assessment methods

A subjective procedure is one in which an observation or outcome arises from the individual; it is dependent on the individual’s own interpretation and therefore cannot be objectively measured or confirmed. The pulse diagnosis method, by definition, is such a procedure. Subjective procedures are prone to ambiguity, and this is clearly reflected in the pulse literature where there may be two quite contradictory descriptions for the same pulse quality. Subjective procedures are also prone to variability in their application; different practitioners may interpret the same patient’s pulse in different ways. Alternatively, the same practitioner may interpret the same patient’s pulses differently on subsequent examinations at the same sitting, as was reported by Craddock (1997).

In part, it is thought that such variability is due to the pulse’s sensitivity to external temporary influences such as physical activity and emotions (Maciocia 2004). In this respect, rather than the reliability of the method being at fault, it is suggested that the patient’s variability is responsible for pulse reading discrepancies (King 2001: p. 37). However, this is somewhat tenuous, particularly in the absence of any standardised terminology or pulse taking procedure, as differences in a patient’s pulse characteristics may be due to inconsistent pulse technique or the pulse taker’s own subjective interpretation of the pulse changes.

Because of the perceived subjectivity not only of pulse diagnosis but also of other aspects of the CM diagnostic procedure, there has been debate about whether the treatment and choice of acupuncture points should be based on conventional medical diagnostic procedures rather than CM theories (Bensoussan 1991, Hammerschlag 1998, Smith 1998, Ulett 1992 cited in King 2001: p. 38). This has particular relevance for CM research involving clinical efficacy, where diagnostic procedures need to be shown to be objective, reliable and reproducible, and also have validity.

(As an aside, the term ‘objective’ refers to information that is uncoloured by the practitioner’s perceptions and interpretation. In the context of pulse diagnosis, the parameters of pulse rate and rhythm are two common CM pulse characteristics that can be objectively verified and the measurements validated by others. Interestingly, this is also reflected in the literature, in which the pulse descriptions for pulses defined by rate or rhythm have a higher consensus among different authors (Table 4.3). Yet many other variables remain subjective, reinforcing the need for unambiguous terminology and concrete operational definitions for applying the pulse taking procedure.)

| Author and source | Definition | Page no. |

|---|---|---|

| Deng (1999) | A slow pulse …refers to three beats per breath, or one less than normal | 117 |

| Guanzhou Chinese Medicine College (1991) | Generally regular rhythm 40–60 beats per minute | |

| Kaptchuk (2000) | Fewer than four beats per respiration | 197 |

| Porkert (1995) | …less than four beats per breath (on the adult) | 38 |

| Wiseman & Ellis (1996) | Three or less beats per respiration | 119 |

4.3. Pulse in changing contexts

The available pulse literature identifies a range of factors as contributing to the variability of the pulse and so needing to be factored into assessment processes when interpreting pulse findings. However, the associated effects on the pulse are often based on assumptions. This is because there have been so few studies investigating the clinical relevancy of even the most basic assumptions underlying radial pulse diagnosis. These assumptions include the relationships between pulse and age, gender, season and body types. For example, it is assumed that the left side pulse in men is stronger than the right side pulse, while in women the reverse is the case. This is stated in the CM classics Nan Jing, Mai Jing and Bin Hue Mai Xue, in addition to similar claims by modern authors such as Hammer (2001: p. 95) and Rogers (2000: p. 88). The claims regarding this and other relationships first appeared over 2000 years ago in a society that was fundamentally very different in terms of culture, society, geography and economics from contemporary modern society. As Hammer (1993: p. 125) noted: ‘Much of what has come down to us as Scripture does not stand the test of time.’

The veracity of long-held CM assumptions may change over time for many reasons. For example, temporal changes in diet, lifestyle, environmental pollution and the changed pace of modern life may impact on the general health of a population, generating different health problems. Similarly, technological advances in biomedical practices and medication have seen the eradication of some diseases and the control of others. Conditions once considered incurable or terminal are now treatable or manageable, and so it can be strongly argued that the related pulses are no longer seen in individuals presenting in primary CM practice in the developed countries. Conversely, conditions once rarely seen in east Asia are occurring with greater frequency in modern society. For example, in Western countries the rise of cardiovascular diseases such as arteriosclerosis and hypertension has been linked to genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors, and these diseases are now occurring more often in Asian populations.

Any of these factors may indeed impact in some way on the pulse characteristics of the general population. Some clinical support for this was provided by the report of the existence of a new pulse quality, tentatively termed the Fluctuating pulse (Zhou & Rogers 1997). Rather than an oversight of the ancient CM practitioners and scholars, they suggested that the appearance of this additional quality was: ‘A pulse quality that developed in modern times in response to a changed, and changing, environment’ (p. 91).

Obviously, the recognition of new pulse qualities may equally mean that some of the traditional pulse qualities may no longer manifest as frequently in the population as may have happened in centuries past. While applying the knowledge and skills contained in older CM texts, modern practitioners should also continue to broaden their knowledge base to encompass changing environment and demographic factors.

4.4. The normal pulse

If pulse qualities are evolving, then the CM image of a normal pulse (usually described as moderate in speed, located neither superficially nor deeply, with an even and regular rhythm) may no longer be valid for contemporary Western urban society, or indeed, contemporary urban Chinese or Japanese society. The notion of what constitutes a normal pulse is further complicated by the assumption that the pulse is prone to seasonal changes, resulting in particular changes that are considered to be normal for the season. Other influences on the pulse include age, gender and time of day. An extensive English-language literature review has not revealed any large-sample demographic study to assess the types of pulse occurring in the general population or their cyclical change through the seasons.

Confusion concerning the features of a normal pulse is not limited to CM practice. In their text on arterial pulses O’Rourke et al (1992: p. 47) point out that it is difficult to define the normal pulse since: ‘The arterial pulse shows a range of patterns under normal conditions. Different patterns are seen … in the same artery at different ages, in the same artery under different physiological conditions.’

This view is similar to that of the CM theory regarding pulse, where it is claimed that a range of pulse qualities constituting the normal pulse may be seen, according to the influence of age, gender, body type or season. Although the classical literature notes the effects of these variables on the pulse, in a modern context there are no data demonstrating these effects or evidence of exactly how they manifest in a clinical setting.

4.5. Reliability and validity of the pulse diagnosis process

Discrepancy between what is written in the classics regarding pulse and what may be occurring in contemporary industrialised populations raises further issues of the validity of the available body of pulse knowledge. Together with inconsistencies of pedagogy and palpatory technique, this brings us to ask a further critical question: Is pulse diagnosis a sound diagnostic tool, and can it be relied on to produce consistent results?

How one chooses to answer this question probably depends on one’s ideological perspective on the practice of pulse diagnosis. From an evidenced-based perspective, the answer is ambivalent as so few studies have been undertaken to confirm or disprove the palpatory technique and its associated assumptions. For example, there are insufficient empirical data either supporting or refuting the notion that changes in the organ system are reflected at the associated radial arterial pulse positions, and too few studies to determine whether practitioners can reliably and consistently discern these changes (Walsh et al 2001: p. 25).

While accepting there is not a large body of firm evidence, there are ways of ensuring that the reliability of pulse taking is maximised, which is the point of this book. This entails ensuring that all abstractions concerning measurement of the pulse are made concrete and the pulse measurement procedure must be shown to be reliable. Stern & Kalof (1996) note that this should involve the development of appropriate operational definitions to determine which variables are being measured and how they will be measured. For pulse diagnosis, it is essential to use concrete operational definitions to ensure that the correct finger positions are located and that consistent methods of palpation are adopted for identifying variations in the pulse wave. If pulse assessment is undertaken the same way every time, then any perceived changes are likely to be the result of illness rather than being variations introduced through inconsistent application of palpatory technique by the practitioner.

Reliability also refers to relating any identified changes in pulse characteristics to pathology through a consistent means of interpretation. This largely depends on the use of the body of literature, the pedagogy, used for categorising any such pulse changes felt. In this sense, reliability can apply not only to the consistent use of a technique by the practitioner but also to the intrinsic validity of the technique. Reliability is, in effect, a product of the literature, theories and systematic clinical use of pulse diagnosis in practice.

4.5.1. Inter-rater reliability

In its basic form pulse taking is a measurement tool for assessing changes in pulse characteristics. A measurement procedure is considered reliable if it produces the same (or similar) scores when separately used on the same set of individuals under the same conditions (Gravetter & Wallnau 1996). This is termed inter-rater reliability. From a clinical perspective, inter-rater (or inter-observer) reliability testing is the process used to substantiate the extent to which practitioners are in agreement with each other regarding patient assessment using a specific measurement tool, in this case pulse diagnosis. The measurement tool is considered to be reliable if it can be shown to reproduce similar results when used by two or more independent assessors to evaluate the same group of patients (King 2001: p. 39). A high level of agreement between the assessors means a high level of inter-rater reliability (Polgar & Thomas 1995).

4.5.1.1. Pulse inter-rater reliability research

Relatively little attention has been paid to testing the validity of the basic theory underlying CM diagnostic procedure. Clinical research into acupuncture and CM focuses primarily on determining the mode of action of acupuncture (involving identification of neurological and biochemical pathways), and herbs (receptor interactions and physiological effects on function) (Lewith & Vincent 1998). Relatively few studies have been carried out to evaluate the reliability of CM diagnostic processes. The existing studies concerning pulse diagnosis have generally reported low levels of inter-rater reliability in relation to the agreement about pulse and the perceived differences in pulse characteristics.

Practitioner inter-rater reliability studies (King 2001: pp. 40-41)

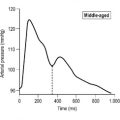

A common finding in the limited research carried out to evaluate the reliability of CM pulse diagnosis is the inverse relationship between the degree of complexity of pulse qualities and levels of inter-rater reliability. A study by Craddock (1997), investigating the reliability of the CM pulse diagnostic process, found that the levels of inter-rater and intra-rater reliability decreased with the increasing complexity of pulse qualities being measured. Since this pilot study included only four practitioners and eight subjects, generalisations of findings require caution. In this study, raters were blinded to subjects, which removed any visual bias from the assessment process. This helped to ensure that the diagnosis was pulse dependent only and not influenced by the physique and appearance of the subject having their pulse assessed (as this is also considered to be part of the CM diagnostic process). The results of a study by Kass (1990) also suggested that levels of inter-rater reliability decreased as more subtle levels of pulse discrimination were required. However, in this study inter-rater reliability was determined using both manual palpation and an electronic pulse detection device, so it is difficult to compare these results with those solely using manual palpation.

The effect of non-standardised pulse terminology and methodology is also reflected in the results of Cole’s British study (1977) of the use of pulse diagnosis in Britain. This research also reported generally low levels of inter-rater agreement between CM practitioners. In addition, a tendency for individual practitioners to favour particular pulse patterns when recording pulse information was also identified: in examining the same group of subjects one practitioner recorded a higher number of ‘normal’ pulses while another practitioner, recorded approximately equal numbers of ‘normal’ and ‘unbalanced’ pulses. Cole surmised that this could have been due to both the practitioners’ preconceived notions about what to expect in the pulse (possibly influenced by other diagnostic criteria available) and to their individual subjective interpretation of the presentation of the pulse characteristics, but unless specific pulse terminology and detailed methodology was provided, it could be equally interpreted as the result of differing measurement techniques and pulse terminology used to evaluate the pulse.

In a study using 5 practitioners and 26 subjects, Birch & Ida (1998, personal communication) found a range of inter-rater reliability agreement in the pulse assessment component of research undertaken to examine diagnostic assessment methods. However, all practitioners had the same access to each subject’s medical history and the raters were able to see the subjects whose pulses they were palpating, which may have had some influence on their evaluation of pulse assessment. The pulse qualities of depth, strength and rate were rated on a 1–5 scale. Using Spearman rank correlation, results ranged from zero (r = −0.004) or no agreement to near-perfect correlation (r = 0.93) or agreement, with most results lying between 0.38 and 0.45.

Because the diversity of the pulse diagnosis systems used in the above studies, it is difficult to compare the findings. However, the generally low levels of inter-rater reliability may be perceived to reflect a systemic weakness: poorly defined pulse definitions and pulse palpation methodology. It is assumed that all practitioners in the same study were purportedly using the same pulse taking system and definitions of pulse qualities. However, unless the exact pulse taking method was prescribed and the pulse qualities clearly defined, the assessors may well have used their own interpretations of the pulse qualities and their own methods of pulse palpation. This is likely, given the wide range of definitions for each of the pulse qualities found in the pulse literature. This also applies to the pulse taking techniques, most notably differences in finding the levels of pulse depth or the traditional pulse positions. These studies reinforce the need for standardisation of both terminology and method when conducting research into aspects of pulse diagnosis.

The relationship between unambiguous, concrete definitions and reliability was clearly demonstrated in a study by King et al (2002), in which levels of inter-rater agreement were statistically significantly better than chance alone. In this study, the descriptive terminology often used to describe the specific CM pulse qualities was not used. Instead, the pulse was broken down into simple components, termed parameters, that related to the actual tactile sensations perceived under the fingers during palpation, but which, when reconstructed, also form the traditional pulse qualities. By operationally defining each parameter, the reliability of the pulse measurement system was demonstrated by two independent assessors. A high level of inter-rater reliability was also demonstrated in a replication phase of the study.

Subsequent studies have shown this parameter method is reliable for pulse characteristic evaluation when used in the context of CM, limiting the source of variability between assessors (King et al 2002, King et al 2006, Walsh 2003, Walsh & Cobbin 2001). In this way, developing a pulse pedagogy that is unambiguous and clearly defined assists in achieving reliability of pulse measurement.

Relevant inter-rater reliability research on pulse has generally focused on practitioners. There has been little investigation of a student’s ability to learn pulse diagnosis and implement pulse theory in the discrimination of radial pulse characteristics. This is surprising, since it is as a student that potential practitioners must learn correct technique and appropriate pulse taking procedures and reliable pulse diagnosis (Walsh et al 2001).

The inconsistent interpretation of pulse types by students, and even practitioners, may be attributed primarily to pulse descriptions that are open to subjective interpretation. Finch & Crunkilton (1993) describe this as ‘constraints of content’ (p. 164); stating that it is content, rather than the inability of the students or the practitioners to integrate information, that inhibits the learning process. This view was supported by a study to assess the inter-rater agreement levels among CM students (Walsh et al 2001), where student participants failed to maintain the number of pulse characteristics for which statistically significant agreement levels were achieved from the initial baseline measures over the following 12 month period. Using a single-blind study design and large sample size, students were tested on three occasions, at the beginning of pulse diagnosis classes (C1), at the completion of the 14 week pulse classes (C2) and one year later (N = 35, 29, 20). Surprisingly, the last collection showed the lowest level of inter-rater agreement among the students. In addition, of the three collections, the second collection alone showed a level of agreement greater than that expected by chance. Walsh found that overall levels of agreement about some basic pulse characteristics (such as depth, speed and length) differed very little from those obtained by chance alone. The study’s findings showed a decrease in the number of pulse characteristics for which inter-rater agreement levels were achieved over time with exposure of the cohort to further curriculum studies (C3) as compared to frequency levels achieved at C2. Significantly, in C1 and C2, the participants used pulse descriptions from a single source in their CM course: the class notes. A further 12 months’ exposure to a set curriculum and extracurricular reading of the CM literature may have contributed to an increased variance in the students’ ability to reach consensus in discriminating differences in the pulse at C3. It was surmised that, rather than stemming from an inability to learn pulse diagnosis, low levels of agreement reflected the conflicting and subjective information about pulse diagnosis in the available CM literature.

4.5.2. Addressing reliability issues

If the practitioner interprets the pulse sensation using a specific set of rules that allows others to understand why and by what means the pulse sensation was interpreted, this begins to establish reliability. This should be the role of pulse terminology: to provide a framework for identifying which procedures were used, how these were applied in palpating the pulse and why a decision regarding the pulse in terms of health or pathology was made. This requires a standardised system of pulse terminology that is still relevant to contemporary clinical practice of pulse diagnosis, but is not subject to the limitations of the traditional literature.

Wiseman & Ye (1999) emphasise the necessity for a standard terminology for unequivocal communication in Chinese medicine. However, this may result in overclassifying pulse terminology to the point where it no longer has any clinical relevance to the practitioner or to aspects of the pulse wave being palpated. As O’Rourke et al (1992) quoted Broadbent who was referring to Galen’s pulse descriptions, ‘it is easy to confuse the essential features of the important variations in the pulse by overwhelming them in minute distinctions of no practical significance’ (p. 5). It is necessary then, when developing appropriate terminology, to ensure that it remains clinically relevant, so not adding more confusion to the process.

In developing an unambiguous terminology for use with pulse palpation, it is first necessary to determine the essential parameters or the characteristics that are involved in the physical manifestation of the radial pulse. This approach is equally applicable to all pulse assumption systems used in CM; whether founded on lineage teachings, on instructions recorded in the classics or on those found in more contemporary constructs such as Five Phase acupuncture.

Such an approach to developing unambiguous terminology is not a recent concept. Wang Shu-he recognised this in the Mai Jing by applying a name to a group of descriptive terms in identifying the pulse qualities he used. In more recent times Wiseman & Ye (1999: p. 56) discuss the analysis of pulse terminology written by Zhou Xue Hai in 1896, in which he determined that there were four main pulse characteristic parameters:

• position (wèi) at which the pulse could be felt (Cun, Guan or Chi, that is length)

• pace (shò) of the pulse (relating to both rate and rhythm)

• form (xíng) of the pulse (level of depth and width)

• dynamic (shì), i.e. the strength of the pulse on arrival and departure.

In this way, some specific CM pulse qualities could be defined by a single parameter, whereas others are defined by two or more parameters. This method of pulse assessment has been partially touched on by contemporary authors such as Lu (1996) and Townsend & De Donna (1990) and a range of other contemporary texts from various sources. The terminology applied to describing pulses and identification of pulse types used throughout this book employs a similar approach to that detailed by Zhou Xue Hai. We have termed this the pulse parameter method.

From an extensive examination of pulse terminology, it was determined that it is the varying combination of the presence or absence of changes in these parameters that forms the basis of the specific CM pulse qualities. For example, the Sinking pulse (Chén mài) is noted for being felt most forcefully at the deep level of depth (regardless of the overall pulse force) and its lack of presence at the superficial level of depth.

The specific CM pulse qualities can be further categorised into simple and complex CM pulse qualities, according to the number of pulse parameters involved in their presentation. The Intermittent pulse (Dài mài) is categorised as a simple CM pulse quality, as rhythm is the only parameter involved. Conversely the Scallion Stalk (hollow) (kōu mài) pulse is classed as complex because of the involvement of changes in a number of parameters including pulse force, depth, arterial wall tension and width. These parameters and associated CM pulse qualities are discussed in further detail in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7.

4.6. Radial pulse palpation method

As well as differences in the ‘standard’ pedagogy in the literature, there are also differences in palpatory technique and a lack of detailed instruction on how to palpate the pulse. This means that idiosyncratic techniques have evolved for locating the levels of depth of the pulse, each with its own methods.

The CM literature concerning pulse diagnostic methodology is fraught with inconsistencies concerning the numerous techniques for pulse taking. Differences occur within and between pulse diagnosis systems and can be related to the specific assumption systems underlying them, influencing the interpretation of the findings in a diagnostic context. For example, there are varying methods for locating the different levels of the pulse among CM texts. Townsend & De Donna (1990) proposed that the superficial pulse could be found by increasing light pressure until a definite pulse could be felt. Other texts suggested placing the fingertips lightly on the skin surface without applying pressure (Deng 1999Li (Huynh trans) 1981, Wiseman & Ellis 1996). The methods of examining the deep level of the pulse were also varied, with simplistic instructions such as ‘felt by pressing firmly’ (Wiseman & Ellis, 1996) or ‘the physician presses quite hard’ (Kaptchuk 2000). Townsend & De Donna (1990) suggested compressing the pulse until it vanished and then decreasing the pressure slightly until the pulse returned, while another author suggested pressing down to the area between the tendon and bone (King 2001).

Generally, CM texts tend not to fully define all aspects of the pulse taking procedure. Instead emphasis is placed on the clinical indications of the different CM pulse qualities and associated disease patterns, while neglecting the very methods used to identify them. This is reflected in the ambiguous and often contradictory pulse definitions. Confusion often occurs over terms used to name specific CM pulse qualities and others that are used as descriptive terms. For example, the Firm pulse (Lílo mài) is described in one text (Lu 1996) as being deep, forceful, large, wiry and long and the indications of its solitary presence in each of the individual positions is described. Yet in the same text, the Long pulse (Chíng mài) is defined as being longer than the normal length of Cun, Guan and Chi, therefore raising the question of how a pulse that is ‘long’ could possibly be present only in a single pulse position.

The subjective methods of the CM classical literature and the use of analogies to define the amount of pressure exerted to find specific levels also have little relevance to modern-day experience, and only confuse the application of techniques further. For example, in the Fifth Difficult Issue of the Nan Jing, the pressure needed to distinguish between the five different levels of depth is described in terms of the weight of a number of beans. In commentaries on the Fifth Difficult Issue discussing how to palpate the different levels of the pulse, there is a comment about the difficulty of understanding the ‘bean method’ (Unschuld (trans) 1986: p. 114), another referenced using pressure to the bone, so it is apparent that there have always been difficulties associated with the various methods of palpation when using descriptive terminology.

4.6.1. Pulse method reliability

Although an unambiguous and concrete terminology is essential for radial pulse diagnosis, it is now apparent that it is equally important to have a consistent method with which to palpate the pulse. A consistent method refers to:

• How and when to apply the pulse taking method: the order of gathering information from the pulse.

• The different techniques (depth, length, strength of application) and required body part (pulse position)

• A consistent application of the techniques in the same way every time.

A consistent method of application is vital, as many of the specific CM pulse types are dependent on the measurement of pulse parameters in specific positions. For example the Long pulse is defined as the presence of pulsations at the three traditional pulse positions Cun, Guan and Chi and beyond these positions, distally and/or proximally. Therefore, it is crucial that the practitioner understands precisely how to locate these positions, in order to be able to identify the CM pulse quality correctly if it is present. This has particular importance in specific methods of radial pulse diagnosis such as the Five Phase method, where the pulses in each of the three traditional pulse positions at the superficial and deep level are rated in terms of overall force: either as deficient, excessive or ‘normal’ (appropriate strength). This is significant because the resulting treatment protocol is primarily based on this diagnostic pulse pattern. Other examples of such systems requiring precise palpatory methods include the Japanese keiraku chiryo system which interprets the organ (Zang Fu) pulse positions into four primary diagnostic categories of organ pairings (Birch 1998: p. 45) and the San Jiao or Three Heater method for looking at a comparative strength differences. Consequently, if the traditional pulse positions are not located in a similar fashion or if there are differences in the methods used to palpate the pulse at different levels of depth, there will be no reliability. The development of a correct and consistent pulse method is detailed in Chapter 5.

References

R Agdal, Diverse and changing perceptions of the body: communicating illness, health, and risk in an age of medical pluralism, Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 11 (S1) (2005) S67–S75.

BAC, The British Acupuncture Council guidelines for acupuncture education. (2000) British Acupuncture Council, London .

A Bensoussan, The vital meridian: a modern exploration of acupuncture. (1991) Churchill Livingstone, Melbourne .

SJ Birch, Testing the claims of traditionally based acupuncture, Complementary Therapies in Medicine 5 (1997) 147–151.

S Birch, Diversity and acupuncture: acupuncture is not a coherent or historically stable tradition, In: (Editor: A Vickers) Examining complementary medicine: the sceptical holist (1998) Stanley Thornes, Cheltenham, pp. 45–62.

S Birch, R Felt, Understanding acupuncture. (1999) Harcourt Brace, London .

BMA, Acupuncture: efficacy, safety and practice. British Medical Association report. (2000) Harwood Academic Publishers, London .

C Cheung, J Belluomini, An overview of pulse types used in traditional Chinese medical differential diagnosis, Journal of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1 (1) (1982) 15–36; (trans).

PC Cole, Pulse diagnosis and the practice of acupuncture in Britain [PhD]. (1977) University of Sussex, Sussex .

D Craddock, Is traditional Chinese medical pulse reading a consistent practice: a comparative pilot study of four practitioners [BAppSc]. (1997) University of Technology Sydney, Sydney .

T Deng, Practical diagnosis in traditional Chinese medicine. (1999) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh .

C Finch, J Crunkilton, Curriculum development in vocational and technical education: planning, content, and implementation. (1993) Allyn & Bacon, Boston .

B Flaws, The secret of Chinese pulse diagnosis. 2nd edn. (1997) Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO .

F Gravetter, L Wallnau, Statistics for the behavioural sciences. 4th edn. (1996) West Publishing Company, St Paul .

Guanzhou Chinese Medicine College, Inspection of the tongue and pulse taking. (1991) Guanzhou Chinese Medicine College, Guanzhou .

L Hammer, Contemporary pulse diagnosis: introduction to an evolving method for learning an ancient art – part 1, American Journal of Acupuncture 21 (2) (1993) 123–139.

L Hammer, Chinese pulse diagnosis: a contemporary approach. (2001) Eastland Press, Seattle .

R Hammerschlag, Methodological and ethical issues in clinical trials of acupuncture, Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 4 (2) (1998) 159–171.

T Kaptchuk, Chinese medicine: web that has no weaver. Revised edn. (2000) Rider Books, London .

R Kass, Traditional Chinese medicine and pulse diagnosis in San Francisco health planning: implications for a Pacific rim city. Online, Available: http://www.acupuncture.com/library/research (1990).

E King, Do the radial qualities of traditional Chinese medicine provide a reliable diagnostic tool?: an examination of pulse relationships stated in modern and classical Chinese texts [MSc]. (2001) University of Technology, Sydney .

E King, D Cobbin, S Walsh, et al., The reliable measurement of radial pulse characteristics, Acupuncture in Medicine 20 (4) (2002) 150–159.

E King, S Walsh, D Cobbin, The testing of classical pulse concepts in Chinese medicine: Left- and right-hand pulse strength discrepancy between males and females and its clinical implications, Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 12 (5) (2006) 445–450.

GT Lewith, CA Vincent, The clinical evaluation of acupuncture, In: (Editors: J Filshie, A White) Medical acupuncture: a western scientific approach (1998) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 205–224; Ch 13.

SZ Li, HK Huynh, Pulse diagnosis. (1981) Paradigm, Brookline, MA ; (trans).

SZ Li, B Flaws, The lakeside master’s study of the pulse. (1998) Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO ; (trans).

Y Lu, Pulse diagnosis. (1996) Shandong Science and Technology Press, Jinan .

G Maciocia, Diagnosis in Chinese medicine: a comprehensive guide. (2004) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh .

Y Manaka, K Itaya, S Birch, Chasing the dragon’s tail. (1995) Paradigm, Brookline, MA .

G Morant, Chinese acupuncture. (1994) Paradigm, Brookline. MA ; (Grinnell L, Leveque M, Jeanmougin C, trans).

NASC, National Academic Standards Committee for Traditional Chinese Medicine. The Australian guidelines for traditional Chinese medicine education. (2001) Australian Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine Association, Brisbane .

J O’Connor, D Bensky, Acupuncture: a comprehensive text. (1981) Eastland Press, Seattle ; (trans and eds).

S Polgar, S Thomas, Introduction to research in the health sciences. 3rd edn. (1995) Oxford University Press, New York .

M Porkert, Classical acupuncture: the standard textbook. (1995) Phainon, Dinkelscherben .

C Rogers, The five keys: an introduction to the study of traditional Chinese medicine, 3rd edn revised. (2000) Acupuncture Colleges Publishing, Sydney .

A Smith, Five Phase diagnosis: the art of science or the science of art, Pacific Journal of Oriental Medicine 5 (1998) 20–26.

P Stern, L Kalof, Evaluating social science research. 2nd edn. (1996) Oxford University Press, Oxford .

G Townsend, Y De Donna, Pulses and impulses: a practitioner’s guide to a unique new pulse diagnosis technique. (1990) Thorsons, Wellingborough .

G Ulett, Beyond yin and yang: how acupuncture really works. (1992) Warren H Green, St Louis .

I Veith, The Yellow Emperor’s classic of internal medicine. (1972) University of California Press, Berkeley .

S Walsh, D Cobbin, K Bateman, et al., Feeling the pulse: trial to assess agreement level among TCM students when identifying basic pulse characteristics, European Journal of Oriental Medicine 3 (5) (2001) 25–31.

S Walsh, The radial pulse: correlation of traditional Chinese medicine pulse characteristics with objective tonometric measures [PhD]. (2003) University of Technology Sydney, Sydney .

Walsh S, Cobbin D 2001 The suitability of the parameter pulse method in teaching undergraduate students: a longitudinal study comparing two methods of pulse diagnosis in the teaching environment. In: Cochran W. (ed) The professionalisation of traditional Chinese medicine. Proceedings of the 6th Australasian Acupuncture and Chinese Herbal Medicine Conference 9 Sept. p. 6

SH Wang, S Yang, The pulse classic: a translation of the Mai Jing. (1997) Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO ; (trans).

WHO, Guidelines on basic training and safety in acupuncture. (1999) World Health Organisation, Geneva .

N Wiseman, A Ellis, Fundamentals of Chinese medicine. Revised edn. (1996) Paradigm, Brookline, MA .

N Wiseman, F Ye, Translation of Chinese medical pulse terms: taking account of the historical dimension, Clinical Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine 1 (1999) 55–60.

Zhou C, Rogers C 1997 The fluctuating pulse: description of a recently identified pulse. In: Cochran W (ed). Towards unity: integrating theory and practice. Proceedings of the Third Australasian Acupuncture and Chinese Herbal Medicine Conference, 13 July. p. 15