Chapter 100 Is Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Superior?

Tears of rotator cuff can be repaired by open or mini-open surgery, or arthroscopically. Codman first described open repair in 1911. Charles Neer is credited with describing the most commonly performed open technique in which acromioplasty with or without resection of the lateral end of clavicle is performed, a bone trough is made at the articular margin for reattachment of the cuff, and transosseous sutures are placed through bone tunnels. Complex sutures are possible because of the open exposure. The advent of a mini-open technique was largely in response to the most important shortcoming of open repair, the necessity for deltoid detachment. In the mini-open technique, the acromioplasty is done arthroscopically, and the cuff repaired through a smaller deltoid-splitting incision. Most recently, advances have allowed the passage of sutures arthroscopically and, therefore, an all arthroscopic rotator cuff repair procedure.

PREFERENCES—A MATTER OF CHOICE

No Level I or II full manuscript published reports of studies favor 1 type of repair over another. Mohtadi and Hollingshead46 compared open with mini-open repairs in a randomized, controlled trial and found no difference in disease-specific quality-of-life outcomes at 1 year (only available Level I evidence on rotator cuff repair). Most of the evidence in the literature is Level III with patients compared retrospectively. These articles often report a surgeon’s transition from an open to a less invasive technique. The open cases serve as a control group for the newer technique.1–5 Such studies are generally poorly controlled and subject to the multiple types of bias inherent in retrospective studies. Retrospective Level IV studies, where cohorts are studied after a particular surgery and analyzed without any comparator group, are most common and are ill-equipped to compare one technique over another.

A surgeon’s preferences are largely dictated by the training the surgeon has received. In agreement with elsewhere in surgery, there appears to be a general trend toward less invasive procedures. The patient choice, however, is clear. Sperling and colleagues6 demonstrate an overwhelming 92% patient preference for arthroscopic shoulder surgery compared with open. Patients anticipated superior functional outcomes and less morbidity with arthroscopic surgery. Moreover, a significant number of patients would prefer to avoid surgery if the only option was an open procedure. In the consumer-driven society of today, patient preferences at least partially explain the trend from open to mini-open, and ultimately to arthroscopic cuff repair.

Assessment of the success of cuff repairs is problematic. Historically, success was measured using relatively crude, nonvalidated assessments of clinical parameters, sometimes assigning a score or groupings such as good or excellent. Modern studies more often use functional outcome measures in which the patients assess their symptoms and ability to function using validated, specially designed questionnaires. There has also been a move recently to look at success in terms of the integrity of the repair using imaging methods such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound. This difference in the way success is measured makes it difficult to compare studies and particularly to compare new and old repair techniques. In general, most authors have reported clinical improvement after all types of cuff repairs. Since Codman’s first description in 1911, many surgeons have reported good results with open repairs. Ellman,7 Hawkins,8 Cofield9, and others report in early articles 72% to 87% good to excellent results on the basis of improvement in pain, function, and strength (Level IV). More recently, Klepps,10 Mellado,11 and Bishop and others12 have shown 71% to 90% good functional results. Whereas Mellado and coworkers11 used the UCLA score (and postoperative MRI studies), others have used American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) and Constant scores. Functional outcome scores of arthroscopic repairs are similar. Burkhart and coauthors,13,14 Gartsman and coworkers,15 Youm and researchers,16 and Bishop and others12 (ASES and Constant) have reported 80% to 93% satisfaction rates using UCLA and Constant scores (Level IV).

Studies of early arthroscopic repairs suggest greater re-tear rates than with open surgery. Improvements in implants and evolution of technique now are reported to produce intact cuffs as often as open repairs. Verma and coworkers17 found a 25% re-tear rate after both mini-open and arthroscopic repairs at 2-year ultrasound follow-up (Level III). Boileau and coauthors18 report a 29% recurrence rate on computed tomography (CT). Fuchs43, and Goutalier44 found a 10% to 30% re-tear rate for small and medium tears with greater rates for massive tears. In the largest multicenter study published to date, Flurin et al.19 assessed 576 arthroscopically repaired cuffs with MRI or CT arthrogram. Seventy-five percent showed no dye leakage compared with a mean of 69% for all published series in the literature for open repairs (Level IV). The authors conclude that arthroscopic repairs yield intact cuffs as often as open repairs. Previously, Gerber and colleagues20 had provided a useful reference point, reporting an MRI-proven recurrent defect in 40% of open repairs of massive tears in 32 shoulders compared with 22% for arthroscopic repairs in 49 shoulders, which included multiple tendon tears21 (Level III). Lafosse41 reports a 12% failure rate on 105 cuffs repaired arthroscopically; 70% of these tears were large or massive.

Verma and coworkers,17 Bishop and others12 have found that good functional results are possible in the absence of a watertight repair. Irrespective of the technique used, however, there is evidence that intact repairs correlate with better functional results. In 1991, Harryman45 suggested that clinical results after open repair correlate with cuff integrity based on ultrasound. Though he found significant satisfaction rates in terms of motion, strength, and pain relief even in the presence of recurrent defects, better results were seen with intact cuffs. Gerber and colleagues20 found that patients who had a re-tear (on MRI) showed less improvement than those who had intact repairs.

COUNTERARGUMENTS

Exposure/Visualization—Seeing Is Believing!

Codman proposed a saber-cut incision in the earliest known description of rotator cuff repair. Since then, anterior, posterior, and extensile approaches have been described. Neer popularized anterior acromioplasty to relieve rotator cuff impingement. All traditional open approaches involve detachment of the deltoid from the acromion to varying degrees. Although the majority of authors recommend minimal deltoid dissection, large and massive tears often require extensive exposure, placing the deltoid attachment at risk. Burkhart and coauthors22 highlight another theoretical disadvantage of open repair. They hypothesize that “open exposure places undue focus on medial-to-lateral transfer of the torn cuff edge to the greater tuberosity bone trough. Because the surgeon’s visualization is limited medially, all the efforts are directed at somehow to bring the cuff to the bone bed. This approach ignores the tear morphology and ultimately results in a repair with greater tension on bone tendon interface. Such repairs are more likely to fail”. Since Burkhart and coauthors’22 work on tear morphology and progression, open repairs have tried to address this issue.

REPAIR STRENGTH

Traditionally, open repairs have used transosseous sutures. Gerber and colleagues23 showed that bone itself provides a poor fixation point. In 8 of 16 shoulders, transosseous fixation failed by the sutures pulling out of the bone early in the postoperative course. This is more relevant in the poor quality osteoporotic bone encountered in the elderly. Though the authors did not test bone anchors, they recommend that transosseous bone fixation must be supplemented with a cortical bone augmentation device. Craft and coworkers24 compared 4 suture anchors with transosseous repairs and found equal initial fixation strength. Reed and coauthors25 found that anchor repair was significantly stronger than transosseous sutures irrespective of bone quality. Chhabra and investigators,26 in a cadaver study, found that double-loaded anchors provide stronger fixation than transosseous repair in the immediate postoperative period.

Though most of these studies tested sutures and repair strength by ultimate load to failure, Hecker and coauthors27 suggest that this may not be the best way to assess suture security because it may not reflect the real clinical situation. Barber and colleagues28 echoed this and argued that cyclic load testing is more appropriate. Cyclic loading occurs with repeated arm motion, applying a modest force on the repair. They tested 4 commonly used absorbable anchors on human cadaveric humeri. After cyclical load testing, they found that none of the anchors showed signs of failure. In addition, Burkhart and coauthors22 have shown that cyclic loading can cause failure with sutures cutting through bone in transosseous repairs.

With the use of new polyblend “super sutures,” the weakest link has all but shifted to the tendon tissue. Cummins and Murrell,29 Gartsman,30 and others have shown that the new sutures hardly ever break, and the failure to load strength far exceeds 200 N for the commonly used No. 2 sutures compared with Ethibond or other commonly used sutures.

Tendon tissue quality and the suture-tendon interface are the only remaining areas of concern in achieving a stable and durable repair. Whereas the former is beyond the surgeon’s control, the latter can be favorably influenced by more complex suture configurations. Complex suture passes such as the Mason Allen configuration are believed to yield the strongest interface38. Because these are difficult to pass arthroscopically, this has provided an argument for superior strength of open repairs. Arthroscopy advocates have countered by demonstrating nearly the same construct strength with subtle modifications, which are possible to do arthroscopically.31–33 Burkhart and Brady,34 on the other hand, have advocated simple suture configuration with double-loaded anchors. In a biomechanical study, they calculated that maximal load per suture does not exceed 37.7 N if double-loaded anchors are placed 1 cm apart. Simple suture configurations are enough to withstand this load.

REHABILITATION AND RECOVERY

Gerber and colleagues23 and others have found that most of the failures occur in the early postoperative period. Thus, irrespective of type of repair, it needs to be protected in the first 4 to 10 weeks. The type of rehabilitation is usually based on the size of tear and tissue quality. After the initial protection period, many authors1,13 have observed an earlier return to functional range of motion after arthroscopic repair.

COMPLICATIONS

Deltoid detachment and atrophy have been reported to occur in 3% to 18% of open rotator cuff repairs. Similarly, infection has affected the result in 1% to 3% of open repairs.35 Recovery of motion in the early postoperative period (first 3 months) after open repairs usually lags behind arthroscopic repairs, though results in terms of range of motion are comparable at 1 year.1,5 As discussed earlier, re-tear as a complication in small and moderate tears is reportedly similar for arthroscopic and open repairs, but some studies have suggested that there may be a greater incidence of re-tear in arthroscopic repair of massive tears.12 Nho found 6 cases of subacromial impingement in the mini-open group compared with 1 in the arthroscopic group that needed repeat surgery. Overall, he found 14 complications in 473 patients (prevalence rate, 3%) in the arthroscopic group compared with 27 complications in 411 patients (prevalence rate, 6.6%) in mini-open group.

Arthroscopic surgery is the choice of most of our patients. It permits better visualization and detects coexisting pathology, which allows a planned and systematic approach to management. The repair construct is strong and can withstand physiologic loads. The complication rate is low, though there may be an increased incidence of re-tears in massive tears. Fortunately, functional outcomes even in these cases are generally improved and the most recent reports suggest that, as techniques improve, equivalent or even better results are being achieved in large tears repaired arthroscopically. Besides, recent reports of Flurin, Cole, and Lafosse show better or equivalent results in large or massive tears repaired arthroscopically. In fact, literature comparison of 2 types of repair at various points of time since the earlier 1990s shows a distinct trend of continuously improving results with arthroscopic repairs. Cost concerns have not been specifically studied for rotator cuff repairs; however, Wang and coworkers36 and Bohnsack and coauthors,37 in separate studies, found cost of arthroscopic Bankart repair to be less than that of open surgery.

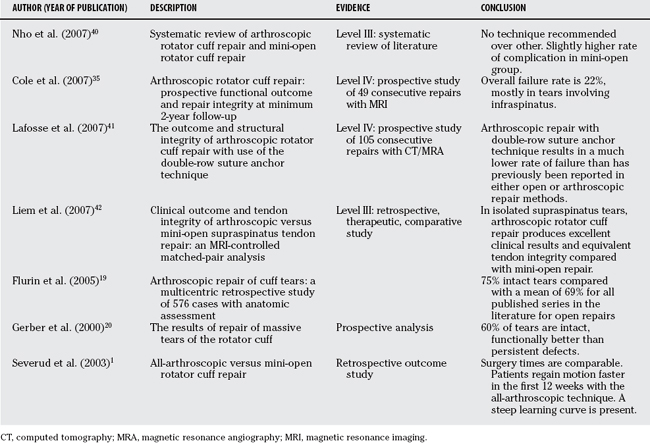

Barring a greater incidence of complications in the case of open repairs, no single factor in the published literature overwhelmingly favors one technique over another. The trend is toward arthroscopic repair as the least invasive technique because it is in many surgical procedures. Based on largely Level III/IV evidence available, it is our opinion that arthroscopic cuff repair seems to be a superior technique in skilled hands. However, the absence of Level I studies prevents us from making a grade A recommendation. Our recommendation is, therefore, a grade C recommendation in favor of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Prospective, randomized multi-center trials are currently being conducted by groups such as JOINTS Canada and should provide more definitive answers in the near future. Tables 100-1 and 100-2 provide a summary of recommendations and levels of evidence.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

| Rotator cuff repair should be performed arthroscopically. | C |

1 Severud EL, Ruotolo C, Abbott DD, et al. All-arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: A long-term retrospective outcome comparison. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:234-238.

2 Ide J, Maeda S, Takagi K. A comparison of arthroscopic and open rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1090-1098.

3 Kang L, Henn RF, Tashjian RZ, et al. Early outcome of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: A matched comparison with mini-open rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:573-582. e1–e2

4 Yamaguchi K, Ball CM, Galatz LM. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair transition from mini-open to all-arthroscopic. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 390; 2001; 83-94.

5 Baker CL, Liu SH. Comparison of open and arthroscopically assisted rotator cuff repairs. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:99-104.

6 Sperling JW, Smith AM, Cofield RH, et al. Patient perceptions of open and arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:361-366.

7 Ellman H, Hanker G, Bayer M. Repair of the rotator cuff. End-result study of factors influencing reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:1136-1144.

8 Hawkins RJ, Misamore GW, Hobeika PE. Surgery for full-thickness rotator-cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1349-1355.

9 Cofield RH: Rotator cuff disease of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 67:974–979.

10 Klepps S, Bishop J, Lin J, et al. Prospective evaluation of the effect of rotator cuff integrity on the outcome of open rotator cuff repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1716-1722.

11 Mellado JM, Calmet J, Olona M, et al. Surgically repaired massive rotator cuff tears: MRI of tendon integrity, muscle fatty degeneration, and muscle atrophy correlated with intraoperative and clinical findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1456-1463.

12 Bishop J, Klepps S, Lo IK, et al. Cuff integrity after arthroscopic versus open rotator cuff repair: A prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:290-299.

13 Burkhart SS, Danaceau SM, Pearce CEJr. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: Analysis of results by tear size and by repair technique—margin convergence versus direct tendon-to-bone repair. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:905-912.

14 Burkhart SS, Barth JR, Richards DP, et al. Arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears with stage 3 and 4 fatty degeneration. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:347-354.

15 Gartsman GM, Khan M, Hammerman SM. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:832-840.

16 Youm T, Murray DH, Kubiak EN, et al. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: A comparison of clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:455-459.

17 Verma NN, Dunn W, Adler RS. All-arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: A retrospective review with minimum 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:587-594.

18 Boileau P, Brassart N, Watkinson DJ, et al. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus: Does the tendon really heal? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1229-1240.

19 Flurin PH, Landreau P, Gregory T. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness cuff tears: a multicentric retrospective study of 576 cases with anatomical assessment. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2005;91(S8):31-42. [Article in French]

20 Gerber C, Fuchs B, Hodler J. The results of repair of massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:505-515.

22 Burkhart SS, Danaceau SM, Pearce CEJr. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: Analysis of results by tear size and by repair technique—margin convergence versus direct tendon-to-bone repair. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:905-912.

23 Gerber C, Schneeberger AG, Perren SM, et al. Experimental rotator cuff repair. A preliminary study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1281-1290.

24 Craft DV, Moseley JB, Cawley PW, et al. Fixation strength of rotator cuff repairs with suture anchors and the transosseous suture technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:32-40.

25 Reed SC, Glossop N, Ogilvie-Harris DJ. Full-thickness rotator cuff tears. A biomechanical comparison of suture versus bone anchor techniques. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:46-48.

26 Chhabra A, Goradia VK, Francke EI, et al. In vitro analysis of rotator cuff repairs: A comparison of arthroscopically inserted tacks or anchors with open transosseous repairs. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:323-327.

27 Hecker AT, Shea M, Hayhurst JO, et al. Pull-out strength of suture anchors for rotator cuff and Bankart lesion repairs. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:874-879.

28 Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing of biodegradable suture anchors containing 2 high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:355-360.

29 Cummins CA, Murrell GA. Mode of failure for rotator cuff repair with suture anchors identified at revision surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:128-133.

30 Gartsman GM. All arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32:501-510.

31 Sileo MJ, Ruotolo CR, Nelson CO, et al. A biomechanical comparison of the modified Mason-Allen stitch and massive cuff stitch in vitro. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:235-240. 240.e1–2,

32 Schlegel TF, Hawkins RJ, Lewis CW, et al. An in vivo comparison of the modified Mason-Allen suture technique versus an inclined horizontal mattress suture technique with regard to tendon-to-bone healing: A biomechanical and histologic study in sheep. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:115-121.

33 Klinger HM, Steckel H, Spahn G, et al. Biomechanical comparison of double-loaded suture anchors using arthroscopic Mason-Allen stitches versus traditional transosseous suture technique and modified Mason-Allen stitches for rotator cuff repair. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2007;22:106-111.

34 Burkhart SS, Brady PC. A Cowboy’s Guide to Advanced Shoulder Arthroscopy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006;34-35.

35 Cole BJ, McCarty LP3rd, Kang RW, et al. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: prospective functional outcome and repair integrity at minimum 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5):579-585.

36 Herrera MF, Bauer G, Reynolds F, et al. Infection after mini-open rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(6):605-608.

37 Wang C, Ghalambor N, Zarins B, et al. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair: analysis of patient subjective outcome and cost. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(10):1219-1222.

38 Bohnsack M, Brinkmann T, Rühmann O, et al. Open versus arthroscopic shoulder stabilization. An analysis of the treatment costs. Orthopade. 2003;32(7):654-658.

39 Burkhart SS, Diaz Pagan JL, Wirth MA, et al. Cyclic loading of anchor-based rotator cuff repairs: confirmation of the tension overload phenomenon and comparison of suture anchor fixation with transosseous fixation. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(6):720-724.

40 Nho SJ, Shindle MK, Sherman SL, et al. Systematic Review of Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair and Mini-Open Rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:127-136.

41 Lafosse L, Brozska R, Toussaint B, et al. The outcome and structural integrity of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with use of the double-row suture anchor technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(7):1533-1541.

42 Liem D, Bartl C, Lichtenberg S. Clinical outcome and tendon integrity of arthroscopic versus mini-open supraspinatus tendon repair: a magnetic resonance imaging-controlled matched-pair analysis. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(5):514-521.

43 Fuchs B, Gilbart MK, Hodler J. Clinical and structural results of open repair of an isolated one-tendon tear of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(5):514-521.

44 Goutallier D, Postel JM, Gleyze P, Leguilloux P. Influence of cuff muscle fatty degeneration on anatomic and functional outcomes after simple suture of full-thickness tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(6):550-554.

45 Harryman DT2nd, Mack LA, Wang KY. Repairs of the rotator cuff. Correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(7):982-989.

46 Mohtadi NG, Hollingshead SK, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing open to arthroscopic acromioplasty with mini-open rotator cuff repair for full-thickness rotator cuff tears: disease-specific quality of life outcome at an average 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1043-1051.