Chapter 9 IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

DEFINITIONS AND CATEGORIES

If there is no structural abnormality to explain the symptoms, and symptoms such as pain or discomfort are associated with changes in bowel habit, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) can be diagnosed. The most stringent definitions for functional gastrointestinal disorders have been provided by the Rome Committee, an international working party. The Rome III criteria for IBS are summarised in Table 9.1. Essentially, IBS can be diagnosed when structural lesions are absent (or unlikely based upon the clinical presentation) and the patient suffers from chronic or relapsing abdominal discomfort or pain associated with an abnormality of bowel movements (constipation, diarrhoea or alternating diarrhoea and constipation). Bloating is also common.

TABLE 9.1 Diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome (Rome III)

| Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort for at least 3 months, and symptoms at least 3 days/month associated with two or more of the following: |

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of IBS ranges from 10% to 20% in Western countries, and it is just as common in India, Japan and China. Only one out of three people who have symptoms of IBS seek medical attention. Generally, those who have more severe symptoms seek medical help. IBS is more prevalent in females. While IBS is not life-threatening, it is remarkable that affected patients have a substantial number of days off work, and thus society has to cope with the burden of IBS too.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF IBS

MANAGEMENT

Diagnostic tests

The diagnosis of IBS is based on patient descriptions of common symptoms and, in particular, abdominal pain or discomfort accompanied by changes in stool form or frequency, often associated symptoms such as bloating and distension. A review of the literature shows that, in patients with no alarm symptoms, the Rome criteria have a positive predictive value of approximately 98%, and that additional diagnostic tests have a yield of 2% or less. The diagnostic evaluation ideally should also include a psychosocial assessment specifically addressing any history of sexual or physical abuse because these issues significantly influence management strategies and treatment success.

The need for additional diagnostic tests such as thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) may depend on the symptom subtype. For example, for constipation-predominant symptoms, a therapeutic trial of fibre supplementation may be sufficient. The American Gastroenterological Association guidelines recommend that in patients who do not respond to fibre, confirmation of slow colonic transit with a whole gut transit test, or evaluation for obstructed defecation with anorectal motility and balloon expulsion test, might be indicated. In patients with diarrhoea-predominant symptoms, clinical judgment will determine the further diagnostic work-up. In patients with relapsing or chronic loose/watery stools, a lactose/dextrose H2 breath test for bacterial overgrowth, serology for coeliac sprue or biopsies of the small intestine (for Giardia, small bowel malabsorption) or colon (for microscopic colitis) might be necessary. Small intestine imaging might be required to rule out Crohn’s disease. Other imaging procedures such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be justified in very selected patients with severe symptoms not responding to therapy, and patients whose symptoms appear to worsen over time. However, none of these can be considered routine diagnostic measures. If clinically indicated, lactose intolerance should be excluded by breath test or an exclusion diet.

Treatment

General measures

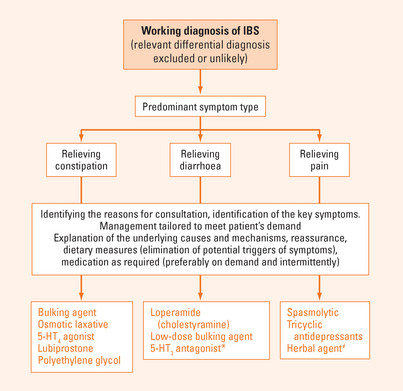

The management approach in patients with IBS is summarised in Figure 9.1. It is most important to address the patient’s needs and to match their individual requirements with the management strategy. Ultimately, it must be recognised that a proper clinical assessment and carefully selected diagnostic measures are important to reassure the patient. Thus, theoretically while the decision to use a specific diagnostic test can be based simply upon the clinical presentation (symptoms, age, family history), this decision making should also address the patient’s needs in order to avoid over- or under-treatment.

General advice to patients should also include dietary recommendations. Foods that trigger symptoms should be identified and systematically avoided. A logbook to document meals and symptoms might be helpful for this purpose. Alternatively, a systematic elimination diet can be attempted. In patients with diarrhoea and bloating, artificial sweeteners sometimes contribute to the manifestation of symptoms. Thus, advice should be given to avoid (at least temporarily) nutrients and sweets with large amounts of artificial sweeteners (including soft drinks, and chewing gum, if used extensively). However, there is currently no diet that has been proven to cure IBS. Removal of foods that have high IgG responses may improve symptoms in a sub-group of patients but remains to be better tested.

IBS is a chronic or relapsing condition. Probably with the exception of fibre, medication should be only used temporarily and doses reduced or drugs discontinued as soon as possible. However, it needs to be acknowledged that a proportion of patients requires long-term maintenance therapy.

Alternative therapies

Alterations of enteric flora may play a role in irritable bowel syndrome. There is emerging evidence that bacterial overgrowth exists in a subgroup of patients. These patients are usually characterised by bloating and abdominal distension. While antibiotic treatment or probiotics appear to improve symptoms, little is known about the long-term outcome.

SUMMARY

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a highly prevalent condition affecting 15% of the population. IBS is defined by chronic or relapsing abdominal symptoms (abdominal pain and/or discomfort) associated with an abnormality of bowel movements (diarrhoea and/or constipation) in the absence of structural lesions. In younger patients (<50 y), if there are no alarm symptoms (e.g. weight loss, per anal blood loss), the diagnosis can usually be made with no additional testing. Communicating the diagnosis and explaining the implications for the prognosis and future management is key for optimal treatment. Based upon the severity of symptoms and the severity of impairment of quality of life, no further therapeutic measures may be required in a subgroup of patients once the diagnosis has been established. A large proportion of patients with IBS suffer from concomitant anxiety or depression. Thus there is frequently the fear of an underlying catastrophic disease as the cause of the symptoms. In this context, further diagnostic measures may need to be done to reassure the patient. Proper dietary assessment and advice can sometimes help identify triggers for symptoms. Pharmacotherapy targets the dominant symptoms but is not disease modifying. Low doses of tricyclic antidepressants may be used in subjects not responding to standard therapy.

American Gastroenterological Association. Medical position statement: irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2105-2107.

Bueno L, de Ponti F, Fried M, et al. Serotonergic and non-serotonergic targets in the pharmacotherapy of visceral hypersensitivity. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(1 Suppl):89-119.

Halvorson HA, Schlett CD, Riddle MS. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome—a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1894-1899. quiz 942

Heading R, Bardhan K, Hollerbach S, et al. Systematic review: the safety and tolerability of pharmacological agents for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome—a European perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:207-236.

Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491.

Mayer EA, Tillisch K, Bradesi S. Review article: modulation of the brain–gut axis as a therapeutic approach in gastrointestinal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:919-933.

Monsbakken KW, Vandvik PO, Farup PG. Perceived food intolerance in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome—etiology, prevalence and consequences. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:667-672.

Park JM, Choi MG, Park JA, et al. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:995-1000.

Riordan SM, Kim R. Bacterial overgrowth as a cause of irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:669-673.