Chapter 23 Irritable bowel syndrome

Introduction

The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has been reported to be 9–22% in the US and 4–35% worldwide.1–5 In the US this burden accounts for 12% of primary care provider visits and 28% of visits to a gastroenterologist.6–8 IBS is a disorder of the brain–gut interactions with both physical and psychosocial components. Key factors appear to be mind–body, nutrition, bacterial flora and immunity.

The common symptoms of IBS include abdominal discomfort, abdominal pain, bloating and irregular bowel habits (Table 23.1).9 Several non-gastrointestinal somatic symptoms, including lethargy, backache, headache, urinary symptoms, irritability of the uterus and dyspareunia suggest a generalised disorder. Usually there is no weight loss or weight gain and pain does not disturb sleep. It is vitally important that the patient has been well screened to exclude other pathological causes for their symptoms, such as coeliac disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, diverticulitis and parasite infection such as Blastocystis Hominis and Giardia, as a clear diagnosis that offers treatment options can offer reassurance to patients. Management should include a positive diagnosis with an explanation of symptoms and their possible causes, and listening to patient’s concerns, thereby addressing any underlying fears and beliefs which may help reduce patient anxiety.

Table 23.1 The criteria for diagnosing irritable bowel syndrome

| Manning criteria(a) |

∗ The second group of criteria included in Rome I are now considered supportive rather than mandatory in the diagnosis.

(a) Manning AP, Thompson WG, Heaton KW, et al. Towards a positive diagnosis of the irritable bowel. BMJ 1978;2:653–4.

(b) Drossman DA, Thompson WG, Talley NJ, et al. Identification of sub-groups of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Int 1990;3:159–72.

(c) Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999;45:II43–7.

(Source: adapted and modified from the British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of the irritable bowel syndrome)9

IBS is a significant problem in general practice, as treatment options are limited and can frequently develop into a chronic condition. Many patients turn to alternative health care to seek symptomatic relief.10 Given the frequency and disabling nature of IBS symptomatology, resorting to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) remedies and therapies has long been a frequent encounter among IBS patients.11 A recent study reports that IBS is poorly understood by patients.12 There is evidence that some IBS patients in primary care experience dissatisfaction and negative attitudes in GP interactions.12 GPs may be the first avenue for IBS patients to voice their frustrations, and hence appropriate education programs for optimal management of patients with IBS may be needed in primary care.12 The health care practitioner is ideally suited to provide comprehensive lifestyle advice including diet, exercise and stress management to assist patients with IBS.

Healthy lifestyles

A healthy lifestyle approach of diet, exercise and stress management is of benefit in adult patients with IBS.13–15 According to a prospective longitudinal study of 52 adult outpatients with IBS, patients attended a structured class that taught health-promoting lifestyle by completing a Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile (HPLP). According to symptom scores on questionnaires, improved response rates to the HPLP at 1 and 6 months were 75% and 83%, respectively. Results revealed significant improvements in pain and overall IBS symptoms such as bloating and discomfort.14

Moreover, in a study that investigated the effects of multidisciplinary education on outcomes in patients with IBS, it was demonstrated that a one-time, multidisciplinary education class for patients with IBS was significantly associated with improvement in symptoms and health-promoting lifestyle behaviors.15

Mind–body medicine

Meditation and/or relaxation

Patients with IBS do well when they are taught to understand the nature of their symptoms, the symptom’s relationship to stress and the practice of regular relaxation exercises. A controlled trial with 35 patients diagnosed with IBS who were randomised to a stress management program involving six 40-minute sessions with a physiotherapist, or to conventional care, demonstrated that two-thirds of the intervention group improved symptomatically, including less episodes of abdominal pain and cramps.16 The benefits persisted over 12 months.

A small controlled treatment study of 16 adults revealed that meditation was superior to control (P = 0.04) in relieving symptoms of IBS.17 A symptom diary at 3-month follow-up, showed significant improvements in flatulence (P<0.01), belching (P = 0.02), bloating (P = 0.05), and diarrhoea (P = 0.03). Further follow-up at 1 year by the same group demonstrated additional improvement in reducing symptoms of pain and bloating with regular meditation practice.18 At the 1-year follow-up they examined changes from the original 3-month follow-up point and noted significant additional reductions in pain (P = 0.03) and bloating (P = 0.04), which tended to be the most distressing symptoms reported of IBS. Hence, it appears that:

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)

There exists research demonstrating the efficacy of CBT in the treatment of IBS. An early published study on a multi-component delivery design that included relaxation, thermal biofeedback, and CBT treatments for IBS compared to an ostensible attention-placebo control (pseudo-meditation and EEG alpha suppression biofeedback) and to a symptom-monitoring control, showed that participants in both treatment conditions showed significant reductions in gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, as measured by daily symptom diaries, and significant reductions in trait anxiety and depression compared with control group.19 The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) symptom reductions held up over a 6-month follow-up. However, this same group in a more recent randomised study of 210 patients with Rome II diagnosed IBS, of at least moderate severity, were randomised to 1 of 3 groups that consisted of:

The results demonstrated that the CBT and psycho-educational support groups continued not to differ on any measure. It was hence concluded that group CBT is not superior to an attention placebo-control condition.20

Hypnosis

There are numerous clinical reports and a body of research on the effectiveness of hypnotherapy in the treatment of IBS. Early randomised clinical trials have demonstrated that hypnotherapy provided a small but significant improvement in abdominal pain, abdominal distension and general wellbeing with lasting benefits in the treatment of IBS.21, 22 Both individual and group hypnotherapy have been reported to be equally effective in alleviating symptoms in patients with IBS. Thirty-three patients were treated with either four 40-minute sessions of hypnotherapy over 7 weeks alone or in a group of 8 patients.23 Twenty improved and 11 participants were virtually asymptomatic. This improvement was maintained at 3 months without further formal treatment.

In a recent study, a large scale audit was conducted on the first 250 unselected patients at a UK centre undergoing hypnosis for IBS.24 Patients underwent 12 sessions of hypnotherapy over a 3-month period and were required to practice at home. Questionnaires before and after treatment demonstrated greater than 70% improvement in all symptom measures, improved quality of life, anxiety and depression (all P< 0.001), fewer consultations and less medication. These benefits persisted for greater than 5 years. It was less useful in males with diarrhoea-predominant IBS, suggesting differences in pathophysiology.24

A recent Cochrane review has concluded that more high-quality research is required.25 The review found that 4 studies including a total of 147 patients met the inclusion criteria. Only 1 study compared hypnotherapy to an alternative therapy (psychotherapy and placebo pill), 2 studies compared hypnotherapy with waiting-list controls and the final study compared hypnotherapy to usual medical management. Data were not pooled for meta-analysis due to differences in outcome measures and study design. The therapeutic effect of hypnotherapy was found to be superior to that of a waiting list control or usual medical management, for abdominal pain and composite primary IBS symptoms, in the short term in patients who fail standard medical therapy. Harmful side-effects were not reported in any of the trials.

Physical activity/exercise

A recent study has reported that associations between GIT symptoms and exercise as well as dietary behaviours may have implications for the treatment of GIT symptoms that includes IBS.26 Lack of exercise is considered as a contributor to the development of IBS although it is not clear what level and duration of exercise would be helpful.13

Yoga

In a controlled study of 22 males (mean age 35 years) with diarrhoea-predominant IBS, the participants were randomised to yoga treatment 2 times a day or symptomatic treatment with loperamide 2–6mg/day for 2 months.27 Both the pharmaceutical and yogic interventions showed a significant decrease of bowel symptoms and anxiety state. However, there was an increase in electro-physiologically recorded gastric activity and enhanced sympathetic reactivity, as measured by heart rate parameters, in the loperamide intervention group suggesting concerns with safety. In a more recent study with 25 adolescents aged 11 to 18 years with IBS who were randomly assigned to either a yoga or wait list control group, it was demonstrated that yoga held promise as an intervention for adolescents with IBS.28 In a recent review it was concluded that non-drug options such as yoga may be proposed to some patients.29

Nutritional influences

Diet

It has been reported that the prevalence of IBS has increased over the last 50 years in countries where a Western-style diet has been prominent or introduced and that 20–65% of patients with IBS attribute their symptoms to something in their food consumption that activates an abnormal response.30

The role of high fibre in the diet — from fruit, vegetables, nuts and seeds — adequate fluid intake, and establishing normal relaxed eating patterns is well established for the maintenance of good gastrointestinal function. This approach is best in those with mainly constipation and less likely to be useful in those with diarrhoea. The role of food sensitivity is not as well established.

A review of the evidence from 12 studies concluded that whilst more research is required, the history of adverse reactions to food in patients with IBS is common.31 The reviewers concluded that there was a high placebo response of 30%, a small fraction of patients with IBS showed immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated food allergy and that there was evidence of an increase in the inflammatory cells present in the gut of some IBS patients. A recent study of 150 outpatients with IBS found elimination diets provided considerable relief in individuals who demonstrated raised immunoglobulin G (IgG) food antibodies by an ELISA test.32 The commonest foods identified were wheat, milk, cashew nuts, whole eggs and yeast. The elimination diet led to 26% greater improvement in fully compliant patients compared with a sham diet after 12 weeks.32

An Australian systematic review of the literature included 7 studies which demonstrated positive response rates to an elimination diet ranging from 15–71% improvement in IBS symptoms.33 Of the double-blind placebo-controlled challenges, food contributed from 6% to 58% of cases. Patients with diarrhoea-predominant IBS showed a higher likelihood of adverse food reactions. The foods most commonly identified as exacerbating symptoms of IBS from the studies included milk, wheat, eggs and amines. Carefully designed controlled clinical trials are reported to be warranted. It is suspected that there is increased immunological activity, perhaps due to stress and poor digestive flora.

Bulk-producing agents

Bulking agents include various types of fibre including psyllium, methylcellulose, corn fibre, calcium polycarbophil, and ispaghula husk.1 Fibre provides bulk to the stool and is prescribed to increase stool frequency and improve stool passage in those who have constipation as a key symptom of IBS.

Whilst some research demonstrates benefit with bulk-producing agents such as psyllium and ispaghula husk (Plantago ovata) in IBS, a recent meta-analysis of 51 double-blind clinical trials found the evidence weak for the use of bulking agents in the treatment of constipation-predominant IBS.34 A recent Cochrane review further concluded that bulking agents may improve constipation and can be used empirically, but should be evaluated at an early stage for individual benefit.35

Herbal medicines

Traditionally a number of herbs such as meadowsweet, golden seal, Aloe vera, German chamomile, slippery elm, marigold, ginger root, passiflora and wild yam have been used for digestive problems such as IBS, but little or no scientific evidence exists to support their efficacy and safety.36 In 1 small study, Aloe vera appeared to be useful in the short-term treatment of constipation, but not IBS.37 Long-term use of Aloe vera should be avoided and has been linked with melanosis coli.

There are only a few herbs that have been clinically trialled for IBS.

Peppermint oil

Peppermint oil is known to have anti-spasmodic properties.38 A 1998 meta-analysis reviewed the use of peppermint oil for IBS but only 5 double-blind, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were suitable for assessment.39 Collectively the studies indicated that peppermint oil could be efficacious for symptom relief in IBS, however, in view of the methodological flaws associated with most studies, no definitive conclusions on efficacy were possible.

In a more recent review40 of 4 of the 5 trials published and reported earlier by Pittler and Ernst there was sufficiently comparable methodologies to attempt a meta-analysis.41 The result of this analysis modestly favoured peppermint oil over placebo (odds ratio [OR], 2.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.56–4.76). This was consistent with the earlier analysis.37 However, this latter analysis showed significant heterogeneity, which limited interpretability (χ2 = 20.81; P<.001).

Recent studies have used enteric-coated peppermint oil capsules. Not included in the meta-analysis, was a randomised, double-blind controlled trial of 42 children (mean age of 12 years) with IBS that were supplemented with enteric-coated peppermint oil capsules or placebo.42 After 2 weeks, 76% of the children receiving peppermint oil had reduced symptoms of IBS and resolution of abdominal pain compared with 19% improvement in the placebo group. In a randomised study performed on a Taiwanese population consisting of 66 men and 44 women (aged 18–70 years) with symptoms of IBS, it was reported that peppermint oil was superior to placebo in improving symptoms after 1 month of therapy.42

Peppermint oil appears to be relatively safe,43 however, side-effects such as heartburn and peri-anal burning/itch have been documented in the literature.

Iberogast (STW 5-II)

Iberogast is a complex herbal preparation.44 Composed of a mixture of aqueous-ethanolic plant extracts from Iberis amara, chamomile leaves, caraway seeds, peppermint leaves, greater celandine, liquorice root, lemon balm leaves, angelica root and St Mary’s thistle. Iberogast has a long history of use in Europe for over 40 years and is newly available in Australia. In a multi-centre study of 208 patients with IBS, the patients were randomised to treatment with Iberogast (STW 5), modified Iberogast (STW 5-II) or placebo.45 STW 5-IIa is a mixture of 6 herbs of Iberogast excluding greater celandine, angelica and milk thistle, but with added bitter candytuft extract or placebo. STW5 was better in reducing the total abdominal symptoms by 54% compared with 27% in the placebo group at 4 weeks. There were no statistical differences between the STW 5-IIa group group and the placebo group. Iberogast (STW 5) and STW 5-II were significantly better than placebo in reducing the total abdominal pain score (Iberogast, P = 0.0009; STW 5-II, P = 0.0005 versus placebo) and the IBS symptom score (Iberogast, P = 0.001; STW 5-II, P = 0.0003 versus placebo) at 4 weeks.45 Further studies are warranted to assess the long term effects of treatment and the mechanism of action.

Chinese herbal medicines (CHMs)

An Australian study demonstrated strong scientific support for the traditional use of Chinese herbs in the treatment of IBS.46 Patients diagnosed with IBS (n = 116) were randomised to receive a standard Chinese herbal formula, an individualised herbal formula or placebo. Significant improvement in IBS symptoms were reported in patients receiving either the Chinese herbal supplement or the individual preparation, compared with those receiving placebo. The average improvement of symptoms was 64%, 76% and 33% respectively. This improvement continued for 14 weeks after therapy was ceased. The group receiving individualised therapy did not relapse after treatment was discontinued, suggesting a change in the person being treated.46

A recent systematic review reports that herbal medicines have therapeutic benefit in IBS.47 A total of 22 studies with 25 CHMs met the inclusion criteria. Four of these studies were of good quality, while the remaining 18 studies involving 17 CHM formulas were of poor quality. Eight of these reports using 9 CHMs showed global improvement of IBS symptoms, 4 studies with 3 CHMs were efficacious in diarrhoea-predominant IBS, and 2 studies with 2 CHMs showed improvement in constipation-predominant IBS. Out of a total of 1279 patients, 15 adverse events in 47 patients were reported with CHMs. No serious adverse events or abnormal laboratory tests were observed. Thus the incidence of the adverse events was low (2.97%; 95% CI: 2.04%−3.90%).47

However, a recent study that investigated the therapeutic efficacy of an ancient herbal Chinese formula in patients with diarrhoea-predominant IBS did not lead to global symptom improvement.48 There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with global symptom improvement between the herbal preparation and placebo groups at week 8 (35% versus 44.1%, P = 0.38) and at week 16 (31.7% versus 33.9%, P = 0.62). Moreover, there was no difference in individual symptom scores and the quality-of-life assessment between the 2 groups at all time points.48

Supplements

Probiotics and prebiotics

To date, there are more than half a dozen randomised, double-blind, cross-over trials that demonstrate the usefulness of probiotics in the management of IBS.49

A recent trial of 50 patients, mean age 40 years with IBS, were randomly assigned to receive either combined probiotics lactobacillus plantarum and bifidobacterium breve or placebo powder for 4 weeks.50 Abdominal pain score after treatment decreased in probiotics group of 38% versus 18% of placebo group after 14 days and of 52% versus 11% after 28 days respectively. The severity of symptoms significantly decreased in probiotic group versus placebo group after 14 days 49.6% versus 9.9% (P<0.001) and these data were confirmed after 28 days (44.4% versus 8.5%, P<0.001).50

A further randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 19 patients with Rome II criteria-defined IBS failed to show benefit after treatment with lactobacillus GG.51 There was a trend toward improvement for a reduction in the number of unformed bowel motions in treated patients with diarrhoea.

Prebiotic agents such as oligofructose and inulin are reported to increase bifidobacteria in faeces and increase stool weight, which makes them attractive in the management of constipation.52 A randomised, controlled, double-blind cross-over study of oligofructose in 21 patients with IBS, however, failed to detect any effects on symptoms, whole-gut transit time, faecal weight, or pH.53

Three recent reviews report that there is substantial biological plausibility as well as research evidence for the use of probiotics in the treatment of IBS.54, 55, 56 However, recommendations for the use of probiotics for IBS are still limited as results of controlled clinical trials are contradictory because they have been performed using different species, dosages, treatment durations and end-points for effective result evaluation. Nevertheless, the role of the enteric flora is an area of great potential in IBS and requires additional trials to further confirm efficacy.

Physical therapies

Acupuncture

Several small studies suggest that acupuncture may be of value for IBS.57, 58 A pilot study of 7 people with IBS found that acupuncture improved general wellbeing and symptoms of bloating.59 Recent Cochrane and systematic reviews for IBS show it is still inconclusive whether acupuncture is more effective than sham acupuncture or other interventions for treating IBS.59, 60

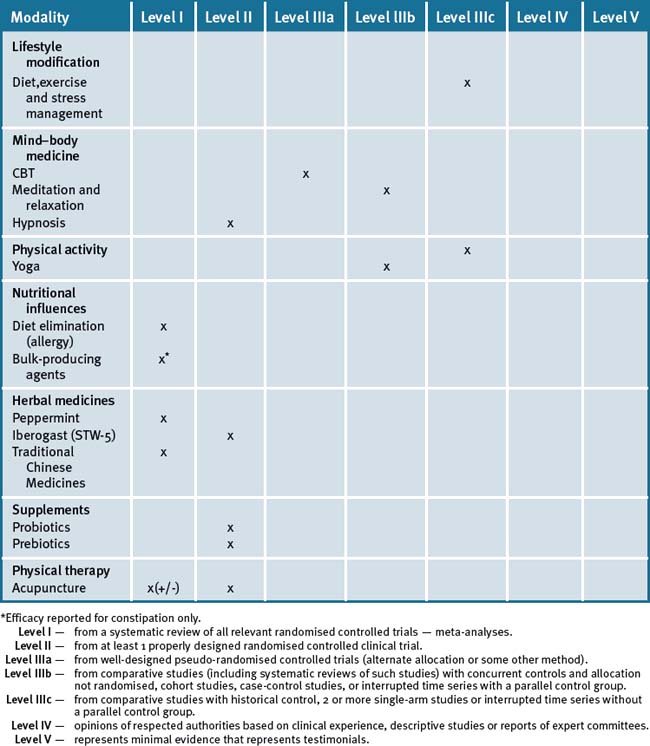

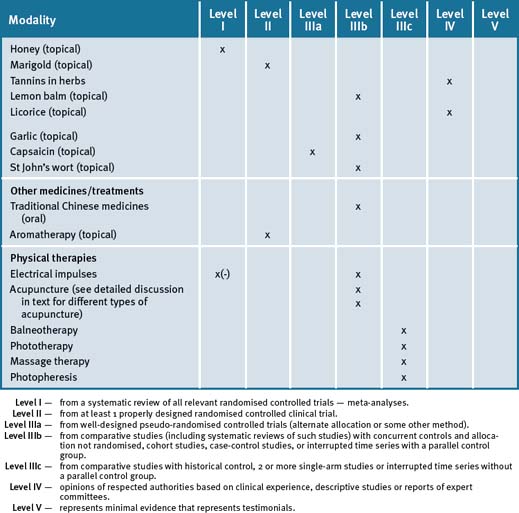

Conclusion

The treatment difficulties encountered with IBS often lead clinicians and patients to seek alternative therapies for the management of IBS-associated symptoms. A number of therapies offer limited scientific support from the existing evidence. The exceptions are the use of diet modification, peppermint oil, Iberogast (STW-5) Chinese herbs, probiotics and psychotherapy which present the best evidence. While Chinese medicine offers only 1 study of high quality, psychological and relaxation therapies offer many studies of lesser quality.40 However these studies have methodological deficits. Many of the studies are further disadvantaged by the absence of a defined control group.

From the current evidence what appears scientifically plausible and feasible is that the treatment of IBS symptoms requires an integrative (multi-modal) approach for symptom management that may, in the first instance, require an individualised approach. This is clearly evident in the high-quality Chinese herb study that hints at a subset of responsive patients with similar needs.46 However, details of what this individualised therapy was were not given.46 A holistic approach to treating IBS should at least include lifestyle changes such as exercise, stress management and dietary adjustments. Table 23.2 summarises the evidence for complementary medicine/therapies.

Clinical tips handout for patients — irritable bowel syndrome

1 Lifestyle advice

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine

5 Dietary changes

Food intolerance

7 Supplements

Bulk-producing agents

Psyllium and ispaghula husk (Plantago ovata)

Other bulk-producing agents include methyl cellulose, corn fibre, calcium polycarbophil.

Probiotics: lactobacillus plantarum and bifidobacterium breve

Lactobacillus GG (acidophilus)

Prebiotics — oligofructose and inulin to increase bifidobacteria

Oligofructose are plant sugars from a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, and cereals.

Consisting of amylase, lipase, protease, tilactase, and cellulose.

Digestive enzymes

Consisting of amylase, lipase, protease, tilactase, and cellulose.

Herbs

Peppermint oil (enteric coated capsules)

Indication: reduces symptoms of IBS and resolution of abdominal pain; flatulence; dyspepsia.

Children > 8 years of age: 0.1–0.2 mL 3 times daily in enteric-coated capsules.

Dyspepsia, peppermint oil 90mg/day combined with caraway oil.

Traditional Chinese herbal medicine (most helpful)

1 Podovei M., Kuo B. Irritable bowel syndrome: a practical review. South Med J. 2006;99(11):1235-1242.

2 Cash B.D., Chey W.D. Advances in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2003;5(6):468-475.

3 Saito Y.A., Locke G.R., Talley N.J., et al. A comparison of the Rome and Manning criteria for case identification in epidemiological investigations of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(10):2816-2824.

4 Drossman D.A., Li Z., Andruzzi E., et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38(9):1569-1580.

5 Drossman D.A., Whitehead W.E., Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome: a technical review for practice guideline development. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:2120-2137.

6 Mitchell C.M., Drossman D.A. Survey of the AGA membership relating to patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol. 1987;92(5 Pt 1):1282-1284.

7 Schuster M.M. Defining and diagnosing irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7(8 Suppl):S246-S251.

8 Switz D.M. What the gastroenterologist does all day: a survey of a state society’s practice. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:1048-1050.

9 Jones J., Boorman J., Cann P. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2000;47(Suppl 2):ii1-ii19.

10 Hussain Z., Quigley E.M. Systematic review: Complementary and alternative medicine in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(4):465-471.

11 Langmead L., Chitnis M., Rampton D.S. Use of complementary therapies by patients with IBD may indicate psychosocial distress. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8(3):174-179.

12 Dhaliwal S.K., Hunt R.H. Doctor-patient interaction for irritable bowel syndrome in primary care: a systematic perspective. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16(11):1161-1166.

13 Wald A., Rakel D. Behavioral and complementary approaches for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23(3):284-292.

14 Colwell L.J., Prather C.M., Phillips S.F., et al. Effects of an irritable bowel syndrome educational class on health-promoting behaviors and symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(6):901-905.

15 Saito Y.A., Prather C.M., Van Dyke C.T., et al. Effects of multidisciplinary education on outcomes in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(7):576-584.

16 Shaw, et al. Stress management for irritable bowel syndrome: a controlled trial. Digestion. 1991;50(1):36-42.

17 Keefer L., Blanchard E.B. The effects of relaxation response meditation on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: results of a controlled treatment study. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39(7):801-811.

18 Keefer L., Blanchard E.B. A one year follow-up of relaxation response meditation as a treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(5):541-546.

19 Blanchard E.B., Schwarz S.P., Suls J.M., et al. Two controlled evaluations of multicomponent psychological treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 1992;30(2):175-189.

20 Blanchard E.B., Lackner J.M., Sanders K., et al. A controlled evaluation of group cognitive therapy in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(4):633-648.

21 Whorwell P.J., Prior A., Colgan S.M. Hypnotherapy in severe irritable bowel syndrome: further experience. Gut. 1987;28(4):423-425.

22 Whorwell P.J., Prior A., Faragher E.B. Controlled trial of hypnotherapy in the treatment of severe refractory irritable-bowel syndrome. Lancet. 1984;2(8414):1232-1234.

23 Harvey R.F., Hinton R.A., Gunary R.M., et al. Individual and group hypnotherapy in treatment of refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 1989;1(8635):424-425.

24 Gonsalkorale W.M., Houghton L.A., Whorwell P.J. Long term benefits of hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:1623-1629.

25 Webb A.N., Kukuruzovic R.H., Catto-Smith A.G., et al. Hypnotherapy for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2007. CD005110

26 Levy R.L., Linde J.A., Feld K.A., et al. The association of gastrointestinal symptoms with weight, diet, and exercise in weight-loss program participants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(10):992-996.

27 Taneja I., Deepak K.K., Poojary G., et al. Yogic versus conventional treatment in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised control study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2004;29(1):19-33.

28 Kuttner L., Chambers C.T., Hardial J., et al. A randomised trial of yoga for adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome. Pain Res Manag. 2006 Winter;11(4):217-223.

29 Ducrotté P. Irritable bowel syndrome: current treatment options. Presse Med. 2007;36(11 Pt 2):1619-1626.

30 Wächtershäuser A., Stein J.M. Nutritional factors and nutritional therapy for irritable bowel syndrome—what is worthwhile? Z Gastroent. 2008;46(3):279-291.

31 Ortolani C., Bruijnzeel-Koomen C., Bengtsson U., et al. Controversial aspects of adverse reactions to food. Allergy. 1999;54:27-45.

32 Atkinson W., et al. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53:1391-1393.

33 Niece A.M., Frankum B., Talley N. Are adverse food reactions linked to irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(11):2184-2190.

34 Lesbros-Pantoflickova D., Michetti P., Fried M., et al. Meta-analysis: The treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(11–12):1253-1269.

35 Quartero A.O., Meineche-Schmidt V., Muris J., et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2005. CD003460

36 Langmead L., Rampton D.S. Herbal treatment in gastrointestinal and liver disease—benefits and dangers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1239-1252.

37 Davis K., Philpott S., Kumar D., et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of aloe vera for irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(9):1080-1086.

38 Hills J.M., Aaronson P.I. The mechanism of action of peppermint oil on gastrointestinal smooth muscle: an analysis using patch clamp electrophysiology and isolated tissue pharmacology in rabbit and guinea pig. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:55-65.

39 Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Peppermint oil for irritable bowel syndrome: a critical review and metaanalysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1131-1135.

40 Spanier J.A., Howden C.W., Jones M.P. A systematic review of alternative therapies in the irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3):265-274.

41 Kline R.M., Kline J.J., Di Palma J., et al. Enteric-coated, pH-dependent Peppermint oil capsules in the treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in children. Journal of Pediatrics. 2001;138:125-128.

42 Liu J.H., Chen G.H., Yeh H.Z., et al. Enteric-coated peppermint-oil capsules in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective, randomised trial. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:765-768.

43 McKay D.L., Blumberg J.B. A review of the bioactivity and potential health benefits of peppermint tea (Mentha piperita L.). Phytother Res. 2006;20(8):619-633.

44 Saller R., Pfister-Hotz G., Iten F., et al. Iberogast: a modern phytotherapeutic combined herbal drug for the treatment of functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract (dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome)-from phytomedicine to “evidence based phytotherapy. Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2002;9(Suppl 1):1-20.

45 Madisch A., Holtmann G., Plein K., et al. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with herbal preparations: results of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:271-279.

46 Bensoussan A., Talley N.J., Hing M., et al. Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Chinese Herbal Medicine. JAMA. 1998;280:1585-1589.

47 Shi J., Tong Y., Shen J.G., et al. Effectiveness and safety of herbal medicines in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(3):454-462.

48 Leung W.K., Wu J.C., Liang S.M., et al. Treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome with traditional Chinese herbal medicine: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1574-1580.

49 Vitetta L., Sali. A. Probiotics, Prebiotics and Gastrointestinal Health. Medicine Today. 2008;9(8):65-70.

50 Saggioro A. Probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. J. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(6 Suppl):S104-S106.

51 O’Sullivan M.A., O’Morain C.A. Bacterial supplementation in the irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:294-301.

52 Gibson G.R., Beatty E.R., Wang X., et al. Selective stimulation of bifidobacteria in the human colon by oligofructose and inulin. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:975-982.

53 Hunter J.O., Tuffnell Q., Lee A.J. Controlled trial of oligofructose in the management of irritable bowel syndrome. J Nutr. 1999;129:1451S-1453S.

54 Guslandi M. Probiotic agents in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. J Int Med Res. 2007;35(5):583-589.

55 Borowiec A.M., Fedorak R.N. The role of probiotics in management of irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9(5):393-400.

56 Quigley E.M. Probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: an immunomodulatory strategy? J Am Coll Nutr. 2007;26(6):684S-690S.

57 Li Y., Tougas G., Chiverton S.G., et al. The effect of acpuncture on gastrointestinal function and disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1372-1381.

58 Chan J., Carr I., Mayberry J.F. The role of acupuncture in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a pilot study. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44(17):1328-1330.

59 Schneider A., Streitberger K., Joos S. Acupuncture treatment in gastrointestinal diseases: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(25):3417-3424.

60 Lim B., Manheimer E., Lao L., et al. Acupuncture for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2006. CD005111