Iron deficiency anaemia

Iron

Iron is a constituent of haemoglobin and rate limiting for erythropoiesis. The metabolism of iron in the body is dominated by its role in haemoglobin synthesis (Fig 12.1). Normally, the total iron content of the body remains within narrow limits: absorption of iron from food (usually up to 3–4 mg/day) must replace any iron losses. Iron is not excreted as such but is lost in desquamated cells, particularly epithelial cells from the gastrointestinal tract. Menstruating women will lose an additional highly variable amount of iron, and in pregnant women the rate of iron loss is about 3.5 times greater than in normal men. The storage forms of iron, ferritin and haemosiderin, constitute about 13% of total body iron. The small peptide hepcidin plays a key role in iron metabolism and absorption (see p. 36).

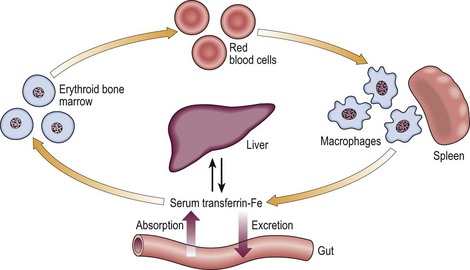

Fig 12.1 The normal iron cycle.

Iron is absorbed from the gut into plasma where it is transported to the bone marrow for haemoglobin synthesis. Dying red cells are engulfed by macrophages in the reticuloendothelial system, and iron is recycled into the plasma for reuse. Iron is transported in the plasma bound to the glycoprotein, transferrin. Transferrin receptors exist on most cells in the body. Of the total 4–5 g of iron in the body only about 0.1% is being recycled at any given time. The rest is in tissue-specific proteins such as haemoglobin (66% of total body iron) and myoglobin, or stored in ferritin.

Causes

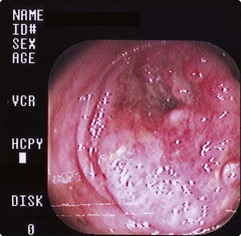

The likely cause will vary with the age, sex and geographic location of the patient (Table 12.1). Iron deficiency is usually caused by long-term blood loss, most often gastrointestinal or uterine bleeding and less commonly bleeding in the urinary tract or elsewhere. Particularly in elderly patients, deficiency may be the presenting feature of gastrointestinal malignancy (Fig 12.2). Hookworm infection is the commonest cause of iron deficiency worldwide. Malabsorption and increased demand for iron, as in pregnancy, are other possible causes. Poor diet may exacerbate iron deficiency but is rarely the sole cause outside the growth spurts of infancy and teenage years.

Fig 12.2 Carcinoma of the colon.

A 53-year-old man presented to his doctor complaining only of tiredness. A blood count was consistent with iron deficiency (Hb 76 g/L, MCV 69 fl) and this was confirmed by a low serum ferritin level. History and examination revealed no obvious cause for his iron deficiency. Colonoscopy revealed a large bowel carcinoma which was successfully resected.

Clinical features

These can be conveniently grouped into three categories:

General symptoms and signs of anaemia (see pp. 14 and 22).

General symptoms and signs of anaemia (see pp. 14 and 22).

Symptoms and signs specific to iron deficiency. Iron is required by many tissues in the body, shortage particularly affecting endothelial cells. Patients with long-standing deficiency may develop nail flattening and koilonychia (concave nails), sore tongues and papillary atrophy, angular stomatitis (Fig 12.3), dysphagia due to an oesophageal web (Plummer–Vinson syndrome) and gastritis. Many patients have none of these and their absence is thus of little significance. Iron deficiency in young children can contribute to psychomotor delay and behavioural problems (see also p. 91).

Symptoms and signs specific to iron deficiency. Iron is required by many tissues in the body, shortage particularly affecting endothelial cells. Patients with long-standing deficiency may develop nail flattening and koilonychia (concave nails), sore tongues and papillary atrophy, angular stomatitis (Fig 12.3), dysphagia due to an oesophageal web (Plummer–Vinson syndrome) and gastritis. Many patients have none of these and their absence is thus of little significance. Iron deficiency in young children can contribute to psychomotor delay and behavioural problems (see also p. 91).

Symptoms and signs due to the underlying cause of iron deficiency. Patients may spontaneously complain of heavy periods, indigestion or a change in bowel habit. Once the diagnosis of iron deficiency is known, it is often useful to retake the history and re-examine the patient with a view to detecting any clue of an underlying disorder. Rectal examination should be routine.

Symptoms and signs due to the underlying cause of iron deficiency. Patients may spontaneously complain of heavy periods, indigestion or a change in bowel habit. Once the diagnosis of iron deficiency is known, it is often useful to retake the history and re-examine the patient with a view to detecting any clue of an underlying disorder. Rectal examination should be routine.

Diagnosis

The blood count

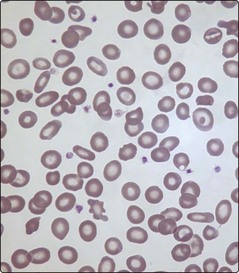

Iron deficiency causes a hypochromic microcytic anaemia. The automated red cell analyser generates a report with haemoglobin, MCV and MCH values below the normal range (see p. 22). There is a variation in red cell size (anisocytosis) reflected by a high red cell distribution width (RDW). A blood film will show characteristic features (Fig 12.4).

Confirmatory tests

Further tests are helpful in confirming the diagnosis (Table 12.2) and excluding other causes of a hypochromic microcytic anaemia (see p. 23). Measurement of serum ferritin is probably the most useful of these tests: a low level always indicates iron deficiency but a normal level does not guarantee normal stores as ferritin is increased in chronic inflammation and liver disease. In occasional difficult cases (e.g. where the patient has recently been transfused) a bone marrow aspirate is helpful in showing absence of iron stores. In practice the most likely confusion is with the anaemia of chronic disease (p. 36).

Table 12.2

Tests to confirm iron deficiency

| Test | Result in iron deficiency | Comment |

| Ferritin | Low | Level increased in chronic inflammation/liver disease |

| Transferrin saturation | Low | Low levels also in elderly and chronic disease |

| Serum iron | Low | Levels fluctuate significantly and low in chronic disease |

| Transferrin concentration1 | High | Useful test as low in anaemia of chronic disease |

| Zinc protoporphyrin | High | Late finding only |

| BM iron | Low | Informative but invasive investigation |

| Serum transferrin receptor level | High | Also high in haemolysis |

| Percentage of hypochromic red cells | High | Limited availability |

| Reticulocyte haemoglobin content | Low | Limited availability |

1Total iron binding capacity (TIBC) may alternatively be used.

Management

This is divisible into investigations of the underlying cause and the correction of iron deficiency.

Investigation of underlying cause

Where the likely cause is apparent, further investigations can be highly selective. Thus in a young woman with severe menorrhagia and no other symptoms it can be assumed that uterine bleeding is the cause of iron deficiency, and investigation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is not necessary. A gynaecological referral would be adequate. Complaints of indigestion or a change in bowel habit should prompt an endoscopy or a colonoscopy or barium enema as first investigations. However, often there are no symptoms suggesting a site of blood loss. The GI tract is by far the most common site in men and postmenopausal women. Faecal occult blood testing is inadequately sensitive to exclude gastrointestinal bleeding and therefore a reasonable approach to this common problem is to commence with colonoscopy and, if normal, to proceed to upper GI endoscopy. If upper GI endoscopy is performed first in an elderly patient and shows a benign ulcerative lesion then assessment of the lower GI tract should probably still be performed as coexistent colonic neoplasms are found in a significant minority of cases. Anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgA) is a simple screening method for coeliac disease. If the GI tract is normal, rare causes of iron deficiency should be considered (see Table 12.1). In 20% of cases of iron deficiency no cause is found.

Correction of iron deficiency

Oral iron is given to correct the anaemia. The normal regimen is ferrous sulphate 200 mg three times a day (providing 195 mg elemental iron daily). Side-effects, including nausea, epigastric pain, diarrhoea and constipation, are best managed by reducing the dosage rather than changing the preparation. An adequate response to oral iron is an increase in haemoglobin of 20 g/L every 3 weeks. Iron is given for at least 6 months to ensure body stores are replete. There are several possible causes of a failure to respond to oral iron (Table 12.3). Parenteral iron (intramuscular or intravenous) can be used where oral therapy is unsuccessful because of poor tolerability or compliance or where there is continuing blood loss or malabsorption. Preparations include iron dextran, iron sucrose and ferric caboxymaltose. Anaphylactic reactions can occur and a test dose may be indicated.