Chapter 4 Investigation, workup and patient preparation before PCI

INTRODUCTION

A anticipation (of possible complications).

There is inevitably some overlap between these elements, all of which require consideration in all patients. The emergency nature of some procedures (e.g. primary PCI for a patient with an acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction) may curtail the time available for preparation of the patient, but should never result in omission of the basic essentials.

PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS

These are needed to allow three questions to be answered:

With few exceptions, PCI should only be considered in a patient with symptoms of coronary artery disease, objective evidence of myocardial ischaemia/infarction and an anatomically suitable lesion(s), as demonstrated by coronary angiography. As a preliminary to such a procedure, therefore, the interventional cardiologist should review the patient’s history and the results of any non-invasive and invasive investigations. While all this information should be available in advance of procedures performed electively, it is now increasingly common that patients, especially those with acute coronary syndromes (ACS: unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction), have combined diagnostic (i.e. coronary angiography) and therapeutic (i.e. PCI) procedures performed. In this situation, it is especially important for the interventional cardiologist to retain a capacity for objective judgement, so that, for instance, a patient who might best be treated surgically does not receive sub-optimal treatment simply because it is ‘convenient’ and it has been scheduled.

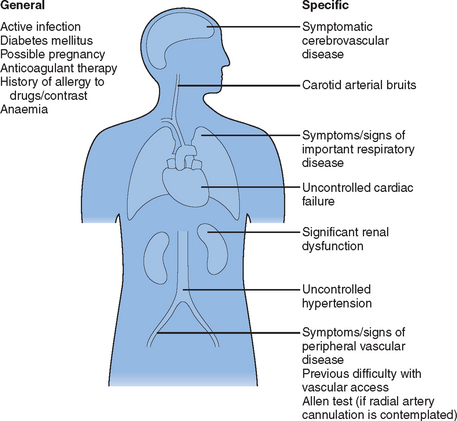

Before arrival in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory, every patient should have a clinical history documented and a physical examination performed (Fig. 4.1). These should be supplemented by some basic investigations, although the number of these will be kept to a minimum in emergency situations (Table 4.1).

| ALL PATIENTS |

It is of particular importance to discover conditions that might increase the technical difficulty or risk of an invasive cardiac procedure. Some such factors can be corrected but awareness of others may lead to changes in peri-procedural drug therapy (see Therapeutics below), the information provided to the patient (see Consent below) or an ability to predict, and hopefully prevent, possible complications (see Anticipation below).

THERAPEUTICS (TABLE 4.2)

Anti-anginal drugs

| DRUG CLASS | ACTION REQUIRED |

|---|---|

| Oral anti-anginal drugs | Continue |

| Cholesterol-lowering therapy | Continue |

| Oral anti-platelet therapy | Ensure that aspirin has been taken |

| ADMINISTER LOADING DOSE OF CLOPIDOGREL (IF NOT ALREADY PRESCRIBED) | |

| Warfarin | Discontinue if possible |

| Measure INR and correct excessive anticoagulation | |

| TAKE APPROPRIATE MEASURES TO AVOID HAEMORRHAGE AT VASCULAR ACCESS SITE | |

| IV Heparin | Continue |

| Measure ACT and consider reduced bolus dose | |

| SC Low molecular-weight heparin | Administer last injection >12 hours prior to PCI (if possible) |

| GP IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists | Continue but consider the use of a reduced, weight-adjusted heparin regime |

| Pre-medication | If necessary, use diazepam 5–20 mg orally |

| Antidiabetic medication | See text |

| Other drug therapy | Continue unchanged |

Oral anti-platelet therapy

Most patients with coronary artery disease are taking Aspirin, which inhibits the platelet cyclo-oxygenase pathway, thus reducing the formation of thromboxane A2, prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin. In the unusual circumstance of a patient not taking regular Aspirin presenting for PCI, this drug (300 mg) should be given, preferably at least two hours before the start of the procedure. Aspirin (75–300 mg daily) should be continued long term thereafter.

As the overwhelming majority of PCI procedures now involve the placement of one or more coronary stents, combined anti-platelet therapy, using Aspirin and Clopidogrel (a thienopyridine derivative that inhibits adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-induced platelet aggregation1), has become normal practice even though Clopidogrel is not currently licensed for this indication. Many patients undergoing urgent PCI procedures for the treatment of ACS may already be taking Clopidogrel but patients undergoing elective or emergency procedures should receive a loading dose of Clopidogrel before the procedure. Available evidence suggests that maximal platelet inhibition is not achieved until at least six hours after a loading dose of 300 mg; this time can be reduced to around two hours by administering a loading dose of 600 mg.2

Anticoagulant therapy

Most patients with acute coronary syndromes are treated with Heparin. Intravenous unfractionated Heparin can be continued until the patient’s arrival in the catheterisation laboratory. Measurement of the activated clotting time (ACT) will then allow the administration of an appropriate bolus of intravenous Heparin, which may not actually be substantially different from that given to a patient not pre-treated with Heparin.3 If a twice-daily regime of subcutaneous low molecular-weight Heparin is being used, the last injection should be given at least 12 hours before any planned coronary interventional procedure.4 At the start of the procedure, an intravenous bolus of unfractionated Heparin can then be given in the usual way. In ‘emergency’ procedures, performed less than 12 hours after the last dose of low molecular-weight Heparin, it is normal practice to use a reduced dose of IV Heparin (<70 U/kg).

Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists

The results of randomised placebo-controlled clinical trials of several agents of this type demonstrate a clear benefit in patients with acute coronary syndromes, those undergoing percutaneous coronary interventional treatment or both. A detailed discussion of the use of such drug treatment is outwith the scope of this chapter – suffice it to say that it is clear that PCI can be performed safely after/during administration of such agents provided that a reduced, weight-adjusted heparin regime is used, in order to reduce the risk of major bleeding.5

Diabetes mellitus6

Although lactic acidosis associated with treatment with Metformin occurs only rarely, it is more common in diabetics with impaired renal function. There have been a number of reports of cases of Metformin-associated lactic acidosis in patients with acute renal failure precipitated by iodinated contrast material, as is used during diagnostic and therapeutic cardiac procedures. This has led to the manufacturer’s current recommendation that Metformin should be discontinued at the time of, or prior to, any such procedure and withheld for 48 hours after the procedure. Treatment should be re-instituted only after renal function has been re-evaluated and found to be normal. In all but emergency cases, renal function should be checked in all patients taking Metformin before the procedure. As Metformin is contraindicated in the presence of abnormal renal function, such patients should have their drug therapy reviewed, although PCI can be performed provided that special precautions are taken7,8 (see Anticipation below).

CONSENT9

It is important to ensure that this information is provided in such a way that the patient has sufficient time to consider it carefully and ask questions before giving consent. In practical terms, it may well be the case that information is given in stages, sometimes by different people working in different institutions. For instance, a patient may be given information about his/her cardiac condition (and a possible need for an invasive procedure) after coronary angiography performed by a physician/cardiologist working in a district general hospital (DGH). Staff at the Regional Cardiac Centre might then provide further information about the proposed procedure, both before and at the time of the patient’s admission for that procedure. It is important that any information given is both consistent and accurate. Medical staff performing interventional procedures should provide their audited results to colleagues in their referring DGHs.10 It is also important that the facts provided are relevant to the patient’s particular clinical situation. For example, it would be misleading to cite an average risk of death during coronary angioplasty as <1% when talking to a patient (or his/her relatives) about performing coronary angioplasty as treatment for cardiogenic shock following acute myocardial infarction – in this fortunately rare clinical situation, the likelihood of survival is considerably less than 99%!

ANTICIPATION

Before and during a cardiac laboratory procedure, it is imperative for the interventional cardiologist to maintain an air of calm and cheerful optimism, as uncertainty will quickly be detected by other members of staff and the patient, with potentially unfortunate consequences. In reality it is important to be thinking at least one step ahead as anticipation of possible problems is a vital step towards preventing them or at least dealing with them swiftly and efficiently if or when they occur. While almost anything can happen to any patient, some are especially vulnerable to particular problems, and appropriate prophylactic measures should be undertaken.

All patients

The ‘easy procedure’ can only be defined in retrospect and one should never assume that an apparently straightforward procedure will necessarily be so. An interventional procedure should only be undertaken by, or under the direct supervision of, a trained operator, with ancillary staff (nurses, technicians and radiographers) who experience a sufficient number of cases in their centre to ensure personal and institutional competence. It is also vital that the procedure is carried out in a fully equipped cardiac catheter laboratory, with an adequate range of equipment and drugs available at all times. This must include full facilities for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, including an intra-aortic balloon pump. There can be no place for a ‘quick angioplasty’ performed by an inexperienced operator in an ill-equipped location.10

Most patients

Although emergency CABG is now required in less than 0.1% of all reported PTCA procedures performed in the UK, the possibility of surgical intervention should be anticipated in all but a very small subgroup of patients in whom a decision is made before the procedure that emergency CABG would be inappropriate. In practical terms this means that coronary interventional procedures should be carried out on patients who have given informed consent for CABG if it should be deemed necessary and have donated a blood sample for blood grouping + formal cross-matching. In other than emergency situations, patients should undergo a three-hour liquid fast and a six-hour solid fast before the procedure. The arrangements for surgical cover for such procedures will vary according to local conditions, but the generally accepted national guideline is that it must be possible to establish cardiopulmonary bypass within 90 minutes of the referral being made to the cardiac surgical service.10

Some patients

Although no patient is immune from the development of ‘contrast nephropathy’, patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction are especially vulnerable. In such patients, measures that may help prevent the development of this condition7 include:

1 Brookes CIO, Sigwart U. Taming platelets in coronary stenting: ticlopidine out, clopidogrel in? Heart. 1999;82:651-653.

2 Longstreth KL, Wertz JR. High-dose clopidogrel loading in percutaneous coronary intervention. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:918-922.

3 Blumenthal RS, Wolff MR, Resar JR, et al. Preprocedural anticoagulation does not reduce angioplasty heparin requirements. Am Heart J. 1993;125:1221-1225.

4 FRISC II Investigators. Invasive compared with non-invasive treatment in unstable coronary-artery disease: FRISC II prospective randomised multicentre study. Lancet. 1999;354:708-715.

5 Topol EJ, Byzova TV, Plow EF. Platelet GPIIb-IIIa blockers. Lancet. 1999;353:227-231. Gill GV, Albert KGMM. The care of the diabetic patient during surgery. In: Alberti KGMM, Zimmet P, DeFronzo RA, et al, editors. International textbook of diabetes mellitus. 2nd edn. Chichester: John Wiley; 1997:1243-1253.

6 Ansell G. Complications of intravascular iodinated contrast media. In: Ansell G, Bettman MA, Kaufman JA, et al, editors. Complications in diagnostic imaging and interventional radiology. 3rd edn. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Science; 1996:245-300.

7 Heupler FA. Guidelines for performing angiography in patients taking Metformin. Cathet Cardiovasc Diag. 1998;43:121-123.

8 General Medical Council. Seeking patients’ consent: the ethical considerations. London: General Medical Council, 1998.

9 Joint working group on coronary angioplasty of the British Cardiac Society and British Cardiovascular Intervention Society. Coronary angioplasty: guidelines for good practice and training. Heart. 2000;83:224-235.

10 Shalansky SJ, Pate GE, Levin A, et al. N-acetylcysteine for prevention of radiocontrast induced nephrotoxicity: the importance of dose and route of administration. Heart. 2005;91:997-999.