Introduction to respiratory care pharmacology

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to:

3. Describe how drugs are named

4. List the various sources of drug information

5. List the various sources used to manufacture drugs

6. Describe the process for drug approval in the United States

8. Differentiate between prescription drugs and over-the-counter drugs

9. Apply the various abbreviations and symbols used in prescribing drugs

10. Describe the therapeutic purpose of each of the major aerosolized drug groups

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Respiratory disorder characterized by respiratory insufficiency that may occur as a result of trauma, pneumonia, oxygen toxicity, gram-negative sepsis, and systemic inflammatory response.

Group of aerosol drugs for pulmonary applications that includes adrenergic, anticholinergic, mucoactive, corticosteroid, antiasthmatic, and antiinfective agents and surfactants instilled directly into the trachea.

Measure of the impedance to ventilation caused by the movement of gas through the airway.

See Trade name.

Name indicating the chemical structure of a drug.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Disease process characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible, is usually progressive, and is associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lung to noxious particles or gases. Diseases that cause airflow limitation include chronic bronchitis, emphysema, asthma, and bronchiectasis.

Name assigned by a manufacturer to an experimental chemical that shows potential as a drug. An example is aerosol SCH 1000, which was the code name for ipratropium bromide, a parasympatholytic bronchodilator (see Chapter 7).

Inherited disease of the exocrine glands, affecting the pancreas, respiratory system, and apocrine glands. Symptoms usually begin in infancy and are characterized by increased electrolytes in the sweat, chronic respiratory infection, and pancreatic insufficiency.

Method by which a drug is made available to the body.

Name assigned to a chemical by the United States Adopted Name (USAN) Council when the chemical appears to have therapeutic use and the manufacturer wishes to market the drug.

Name of a drug other than its trademarked name.

In the event that an experimental drug becomes fully approved for general use and is admitted to the United States Pharmacopeia–National Formulary (USP-NF), the generic name becomes the official name.

Drug or biologic product for the diagnosis or treatment of a rare disease (affecting fewer than 200,000 persons in the United States).

Mechanisms of drug action by which a drug molecule causes its effect in the body.

Study of the interrelationship of genetic differences and drug effects.

Identification of sources of drugs, from plants and animals.

Time course and disposition of a drug in the body, based on its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination.

Study of drugs (chemicals), including their origin, properties, and interactions with living organisms.

Preparation and dispensing of drugs.

Pneumocystis carinii (jiroveci)

Organism causing Pneumocystis pneumonia in humans, seen in immunosuppressed individuals such as those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Written order for a drug, along with any specific instructions for compounding, dispensing, and taking the drug. This order may be written by a physician, osteopath, dentist, veterinarian, and others but not by chiropractors or opticians.

Gram-negative organism, primarily a nosocomial pathogen. It causes urinary tract infections, respiratory system infections, dermatitis, soft tissue infections, bacteremia, bone and joint infections, gastrointestinal infections, and various systemic infections, particularly in patients with severe burns and in patients who are immunosuppressed (e.g., patients with cancer or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]).

Application of pharmacology to the treatment of pulmonary disorders and, more broadly, critical care. Chapter 1 introduces and defines basic concepts and selected background information useful in the pharmacologic treatment of respiratory disease and critical care patients.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

Virus that causes the formation of syncytial masses in cells. This leads to inflammation of the bronchioles, which may cause respiratory distress in young infants.

Art of treating disease with drugs.

Study of toxic substances and their pharmacologic actions, including antidotes and poison control.

Brand name, or proprietary name, given by a particular manufacturer.

Pharmacology and the study of drugs

The many complex functions of the human organism are regulated by chemical agents. Chemicals interact with an organism to alter its function, providing methods of diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of disease. Such chemicals are termed drugs. A drug is any chemical that alters the organism’s functions or processes. Examples include oxygen, alcohol, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), heparin, epinephrine, and vitamins. The study of drugs (chemicals), including their origin, properties, and interactions with living organisms, is the subject of pharmacology.

Pharmacology can be subdivided into the following more specialized topics:

• Pharmacy: The preparation and dispensing of drugs

• Pharmacognosy: The identification of sources of drugs, from plants and animals

• Pharmacogenetics: The study of the interrelationship of genetic differences and drug effects

• Therapeutics: The art of treating disease with drugs

• Toxicology: The study of toxic substances and their pharmacologic actions, including antidotes and poison control

The principles of drug action from dose administration to effect and clearance from the body are the subject of processes known as drug administration, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. These processes are defined and presented in detail in Chapter 2. Table 1-1 summarizes key developments in the regulation of drugs in the United States.

TABLE 1-1

| 1906 | First Food and Drugs Act is passed by Congress; the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and the National Formulary (NF) were given official status |

| 1914 | Harrison Narcotic Act is passed to control the importation, sale, and distribution of opium and its derivatives as well as other narcotic analgesics |

| 1938 | Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act becomes law. This is the current Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to protect the public health and to protect physicians from irresponsible drug manufacturers. This act is enforced by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) |

| 1952 | Durham-Humphrey Amendment defines the drugs that may be sold by the pharmacist only on prescription |

| 1962 | Kefauver-Harris Amendment is passed as an amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. This law requires proof of the safety and efficacy of all drugs introduced since 1938. Drugs in use before that time have not been reviewed but are under study |

| 1970 | Controlled Substances Act becomes effective; this act lists requirements for the control, sale, and dispensation of narcotics and dangerous drugs. Five schedules of controlled substances have been defined. Schedule I to Schedule V generally define drugs of decreasing potential for abuse, increasing medical use, and decreasing physical dependence. Examples of each schedule are as follows: |

| Schedule I | All nonresearch use is illegal; examples—heroin, marijuana, LSD, peyote, and mescaline |

| Schedule II: | No telephone prescriptions, no refills; examples—opium, morphine, certain barbiturates, amphetamines |

| Schedule III: | Prescription must be rewritten after 6 months or five refills; examples—certain opioid doses, anabolic steroids, and some barbiturates |

| Schedule IV: | Prescription must be rewritten after 6 months or five refills; penalties for illegal possession differ from those for Schedule III drugs; examples—phenobarbital, barbital, chloral hydrate, meprobamate (Equanil, Miltown), and zolpidem (Ambien) |

| Schedule V: | As for any nonopioid prescription drug; examples—narcotics containing nonnarcotics in mixture form, such as cough preparations or Lomotil (diphenoxylate [narcotic; 2.5 mg] and atropine sulfate [nonnarcotic]) |

| Orphan Drug Amendments of 1983 | Provides incentives for the development of drugs that treat diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 patients in the United States |

| Drug Price Competition and Patent Restoration Act of 1984 | Abbreviated new drug application for generic medication. Allows the patent to be extended for up to 5 years owing to loss of marketing because of FDA reviews |

| Prescription Drug User Fee Act of 1992 | Reauthorized in 2007. User fees are paid for certain new drug applications by manufacturers |

| Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 | Established standards of dietary supplements. Specific ingredient and nutrition labels must be included on each package |

| Bioterrorism Act of 2002 | More stringent control on biologic agents and toxins |

| Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 | FDA has greater authority over drug labeling, marketing, and advertising. Makes clinical trial information more visible to the public |

For more information, access the FDA website at www.fda.gov.

Naming drugs

• Chemical name: The name indicating the drug’s chemical structure.

• Code name: A name assigned by a manufacturer to an experimental chemical that shows potential as a drug. An example is aerosol SCH 1000, which was the code name for ipratropium bromide, a parasympatholytic bronchodilator (see Chapter 7).

• Generic name: The name assigned to a chemical by the United States Adopted Name (USAN) Council when the chemical appears to have therapeutic use and the manufacturer wishes to market the drug. Instead of a numeric or alphanumeric code, as in the code name, this name often is loosely based on the drug’s chemical structure. For example, isoproterenol has an isopropyl group attached to the terminal nitrogen on the amino side chain, whereas metaproterenol is the same chemical structure as isoproterenol except that a dihydroxy attachment on the catechol nucleus is now in the so-called meta position (carbon-3,5 instead of carbon-3,4). The generic name is also known as the nonproprietary name, in contrast to the brand name.

• Official name: In the event that an experimental drug becomes fully approved for general use and is admitted to the United States Pharmacopeia–National Formulary (USP-NF), the generic name becomes the official name. Because an officially approved drug may be marketed by many manufacturers under different names, it is recommended that clinicians use the official name, which is nonproprietary, and not brand names.

• Trade name: This is the brand name, or proprietary name, given by a particular manufacturer. For example, the generic drug named albuterol is currently marketed by Schering-Plough as Proventil-HFA, by GlaxoSmithKline as Ventolin-HFA, and by Teva as Proair HFA.

Sources of drugs

For example, the prototype of cromolyn sodium was khellin, found in the eastern Mediterranean plant Ammi visnaga; this plant was used in ancient times as a muscle relaxant. Today, its synthetic derivative is used as an antiasthmatic agent. Another example is curare, derived from Chondrodendron tomentosum (a large vine) and used by South American Indians to coat their arrow tips for lethal effect. Its derivative is now used as a neuromuscular blocking agent. Digitalis is obtained from the foxglove plant (Digitalis purpurea) and was reputedly used by the Mayans for relief of angina. This cardiac glycoside is now used to treat heart conditions. The notorious poppy seed (Papaver somniferum) is the source of the opium alkaloids, immortalized in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater.4

• Animal: Thyroid hormone, insulin, pancreatic dornase

• Plant: Khellin (Ammi visnaga), atropine (belladonna alkaloid), digitalis (foxglove), reserpine (Rauwolfia serpentina), volatile oils of eucalyptus, pine, anise

• Mineral: Copper sulfate, magnesium sulfate (Epsom salts), mineral oil (liquid hydrocarbons)

Process for drug approval in the united states

The process by which a chemical moves from the status of a promising potential drug to one fully approved by the FDA for general clinical use is, on the average, long, costly, and complex. Cost estimates vary, but in the 1980s it took an average of 13 to 15 years from chemical synthesis to marketing approval by the FDA, with a cost of $350 million in the United States.5 In a more recent study by DiMasi and associates,6 it was calculated that companies spend almost $900 million on research and development and on preclinical and postclinical trials of a new drug in the current market.

The major steps in the drug approval process have been reviewed by Flieger7 and by Hassall and Fredd.8 Box 1-1 outlines the major steps of the process.

Orphan drugs

An orphan drug is a drug or biologic product for the diagnosis or treatment of a rare disease. Rare is defined as a disease that affects less than 200,000 persons in the United States. Alternatively, a drug may be designated as an orphan if it is used for a disease that affects more than 200,000 persons but there is no reasonable expectation of recovering the cost of drug development. Table 1-2 lists several orphan drugs of interest to respiratory care clinicians.

TABLE 1-2

Examples of Orphan Drugs of Interest to Respiratory Care Clinicians

| DRUG | PROPOSED USE |

| Acetylcysteine | Intravenous administration for moderate to severe acetaminophen overdose |

| α1-Proteinase inhibitor (Prolastin)* | Replacement therapy for congenital α1-proteinase (α1-antitrypsin) deficiency |

| Beractant (Survanta)* | Prevention or treatment of RDS in newborns |

| Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator | Treatment of CF |

| Dornase alfa (Pulmozyme)* | Treatment of CF: reduction of mucus viscosity and increase in airway secretion clearance |

| Nitric oxide gas (INOmax)* | Treatment of persistent pulmonary hypertension of newborns or of acute respiratory distress in adults |

| Tobramycin solution for inhalation (TOBI)* | Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in CF or bronchiectasis |

| Pentamidine isethionate | Prevent Pneumocystis carinii (jiroveci) pneumonia in high-risk patients |

CF, Cystic fibrosis; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome.

*Use has been approved by the FDA.

Compiled from Drug facts and comparisons, St Louis, 2010, Facts & Comparisons, Wolters Kluwer.

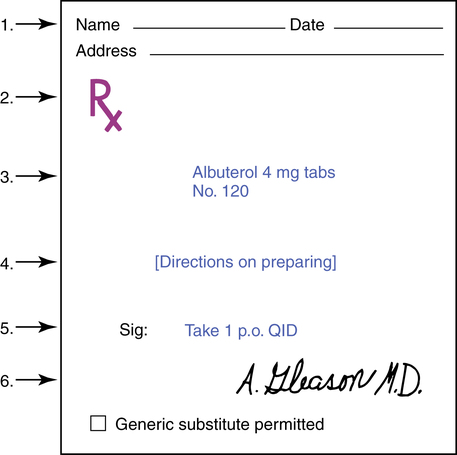

The prescription

The prescription is the written order for a drug, along with any specific instructions for compounding, dispensing, and taking the drug. This order may be written by a physician, osteopath, dentist, veterinarian, and others but not by chiropractors or opticians. The detailed parts of a prescription are shown in Figure 1-1. It should be noted that Latin and English as well as metric and apothecary measures are used for drug orders.

1. Patient’s name and address and the date the prescription was written.

2.  (meaning “recipe” or “take thou”) directs the pharmacist to take the drug listed and prepare the medication. This is referred to as the superscription.

(meaning “recipe” or “take thou”) directs the pharmacist to take the drug listed and prepare the medication. This is referred to as the superscription.

3. The inscription lists the name and quantity of the drug being prescribed.

4. When applicable, the physician includes a subscription, directions to the pharmacist on how to prepare the medication. For example, a direction to make an ointment, which might be appropriate for certain medications, would be “ft ung.” In many cases, with precompounded drugs, counting out the correct number is the only requirement.

5. Sig (signa) means “write.” The transcription or signature is the information the pharmacist writes on the label of the medication as instructions to the patient.

6. Name of the prescriber: Although the physician signs the prescription, the word “signature,” as described in part 5, denotes the directions to the patient, not the physician’s name.

The directions (4 in Figure 1-1) to the pharmacist for mixing or compounding drugs have become less necessary with the advent of the large pharmaceutical firms and their prepared drug products. The importance of these directions is in no way diminished, however, because misinterpretation is potentially lethal when dealing with drugs.

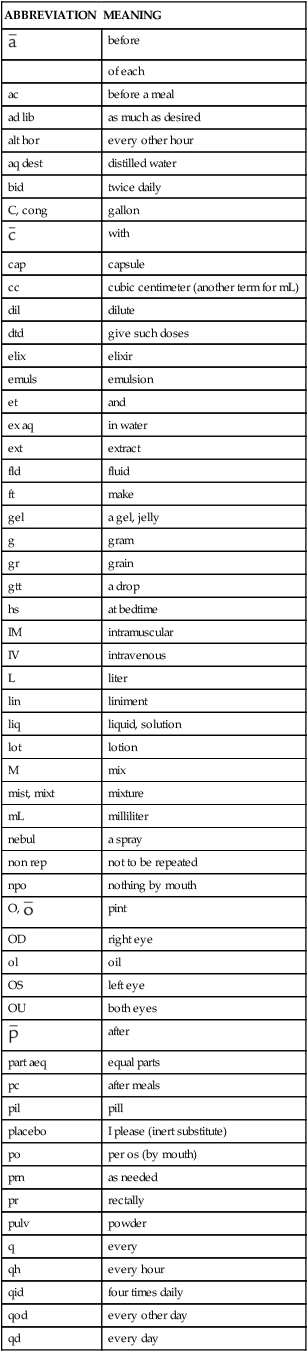

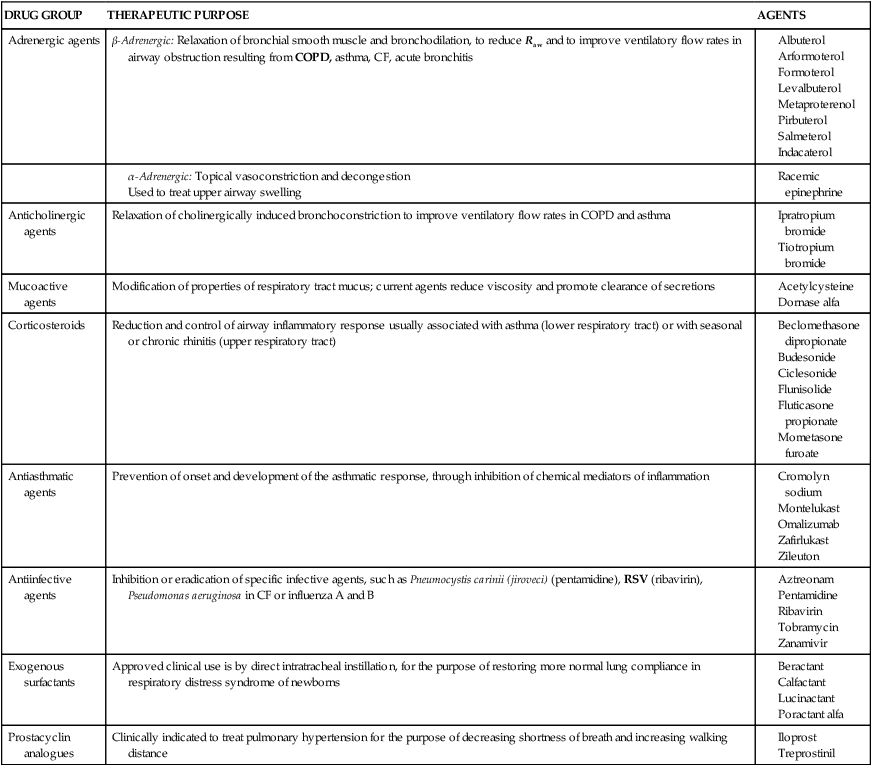

Table 1-3 lists the most common abbreviations seen in prescriptions.

TABLE 1-3

Abbreviations and Symbols Used in Prescriptions*

| ABBREVIATION | MEANING |

|

before |

| of each | |

| ac | before a meal |

| ad lib | as much as desired |

| alt hor | every other hour |

| aq dest | distilled water |

| bid | twice daily |

| C, cong | gallon |

|

with |

| cap | capsule |

| cc | cubic centimeter (another term for mL) |

| dil | dilute |

| dtd | give such doses |

| elix | elixir |

| emuls | emulsion |

| et | and |

| ex aq | in water |

| ext | extract |

| fld | fluid |

| ft | make |

| gel | a gel, jelly |

| g | gram |

| gr | grain |

| gtt | a drop |

| hs | at bedtime |

| IM | intramuscular |

| IV | intravenous |

| L | liter |

| lin | liniment |

| liq | liquid, solution |

| lot | lotion |

| M | mix |

| mist, mixt | mixture |

| mL | milliliter |

| nebul | a spray |

| non rep | not to be repeated |

| npo | nothing by mouth |

O,  |

pint |

| OD | right eye |

| ol | oil |

| OS | left eye |

| OU | both eyes |

|

after |

| part aeq | equal parts |

| pc | after meals |

| pil | pill |

| placebo | I please (inert substitute) |

| po | per os (by mouth) |

| prn | as needed |

| pr | rectally |

| pulv | powder |

| q | every |

| qh | every hour |

| qid | four times daily |

| qod | every other day |

| qd | every day |

| q2h | every 2 hours |

| q3h | every 3 hours |

| q4h | every 4 hours |

| qs | as much as required (quantity sufficient) |

| qt | quart |

| Rx, Rx | take |

|

without |

| sig | write |

| sol | solution |

| solv | dissolve |

| sos | if needed (for one time) |

| spt | spirit |

| sp frumenti | whiskey |

|

half |

| stat | immediately |

| syr | syrup |

| tab | tablet or tablets |

| tid | three times daily |

| tr, tinct | tincture |

| ung | ointment |

| ut dict | as directed |

| vin | wine |

*Not all of these abbreviations are considered safe practice; however, they may still be seen occasionally.

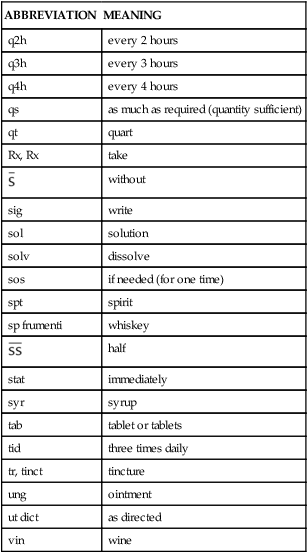

Respiratory care pharmacology: an overview

Aerosolized agents given by inhalation

• Aerosol doses are smaller than doses used for the same purpose and given systemically.

• Side effects are usually fewer and less severe with aerosol delivery than with oral or parenteral delivery.

• The onset of action is rapid.

• Drug delivery is targeted to the respiratory system, with lower systemic bioavailability.

• The inhalation of aerosol drugs is painless, is relatively safe, and may be convenient depending on the specific delivery device used.

The classes of aerosolized agents (including surfactants, which are directly instilled into the trachea), their uses, and individual agents are summarized in Table 1-4.

TABLE 1-4

Common Agents Used in Respiratory Therapy

| DRUG GROUP | THERAPEUTIC PURPOSE | AGENTS |

| Adrenergic agents | β-Adrenergic: Relaxation of bronchial smooth muscle and bronchodilation, to reduce Raw and to improve ventilatory flow rates in airway obstruction resulting from COPD, asthma, CF, acute bronchitis |

CF, Cystic fibrosis; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Raw, airway resistance; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Related drug groups in respiratory care

Additional groups of drugs important in critical care are the following:

• Antiinfective agents, such as antibiotics or antituberculous drugs

• Neuromuscular blocking agents, such as curariform agents and others

• Central nervous system agents, such as analgesics and sedatives/hypnotics

• Antiarrhythmic agents, such as cardiac glycosides and lidocaine

• Antihypertensive and antianginal agents, such as β-blocking agents or nitroglycerin

• Anticoagulant and thrombolytic agents, such as heparin or streptokinase