Introduction to Pelvic

Anatomy 1

The anatomy taught in this book is based on actual cadaveric dissection. This section consists entirely of color drawings constructed from anatomic models (cadavers). This section was added to help the reader orient the dissection photographs to the overall geography of abdomen, pelvis, breasts, and extremities. In several pictures, our artist has used actual photographs of body parts (pelvic bone) into which muscles and ligaments were sketched via computer.

The following terms are used in this section to provide directive relationships: (1) cranial = toward the head; (2) caudal = toward the foot; (3) superior = above; (4) inferior = below; (5) deep = to the interior; (6) superficial = to the surface; (7) medial = toward the midline; (8) lateral = toward the side; (9) beneath = under; (10) anterior = to the belly; and (11) posterior = to the back.

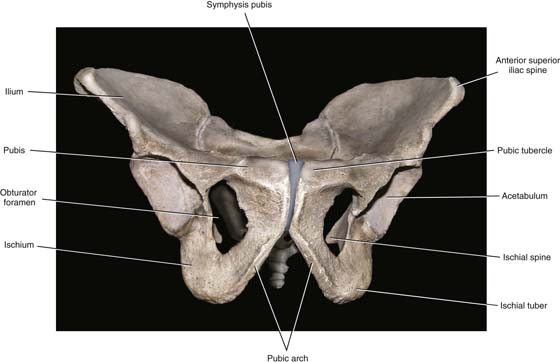

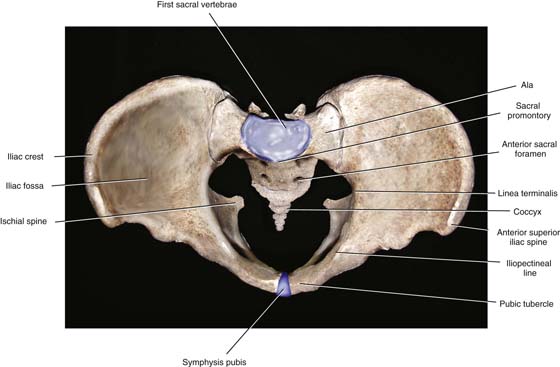

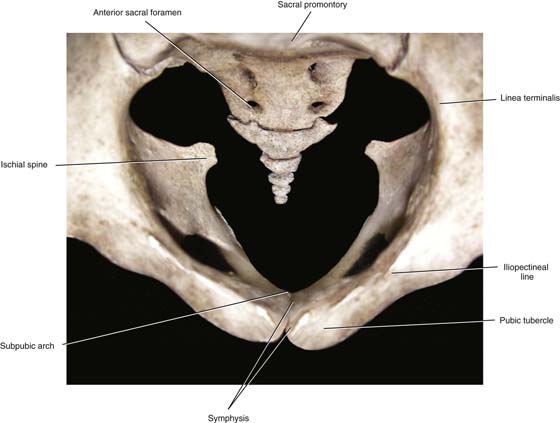

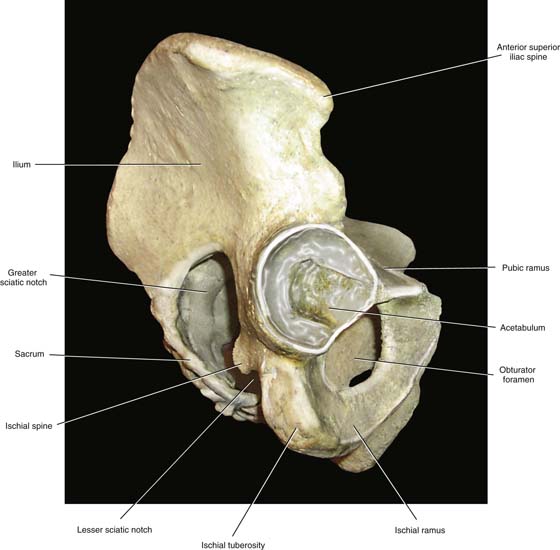

The surgeon needs to be familiar with certain bony landmarks. The pelvic bones consist of the sacrum and coccyx, the ilium, the pubic bone, and the ischium (Fig. 1–1). The first anterior projection of the sacral vertebra is the sacral promontory, and the exaggerated transverse processes form the sacral ala (Fig. 1–2). On both anterior and posterior surfaces are the holes, or foramina, from which nerve roots exit. Articulating with the last sacral vertebra is the coccyx (Fig. 1–3). When the pelvis is observed from above (see Fig. 1–2), the iliac fossa, iliac crest, and anterior superior iliac spine are prominent. The articulations at the sacroiliac joint and the symphysis pubis mark major posterior and anterior joints, respectively. Between the two are the iliopectineal lines and the linea terminalis. Facing the pelvis, the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle mark the boundaries of the inguinal ligament. The two pubic bones form an arch beneath the symphysis pubis. The rhomboid space between ischial and pubic bones is the obturator foramen (see Fig. 1–1). The lowest portion of the ischium forms a broad, rounded accumulation of bone referred to as the ischial tuberosity. Above that structure is a hemispherical socket (acetabulum), where the head of the femur articulates (see Fig. 1–1).

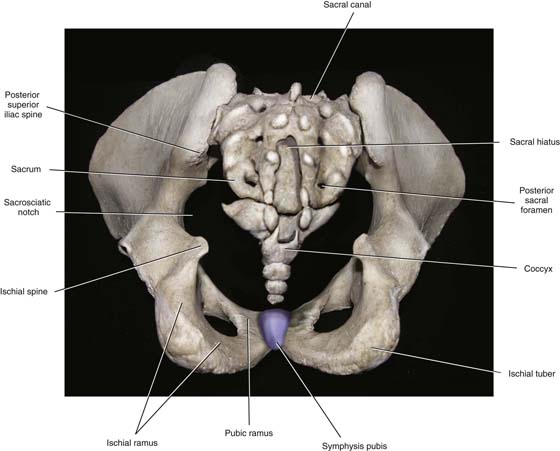

When one faces the back of the pelvis, the sacrum and the sacral canal are visible. The ischial tuberosity, ischial spines, and greater and lesser sacral sciatic notches are identified (Fig. 1–4). From the side, the iliac crest, ischial tuberosity, ischial spine, greater sciatic notch, and lesser sciatic notch are seen, as is the obturator foramen (Fig. 1–5).

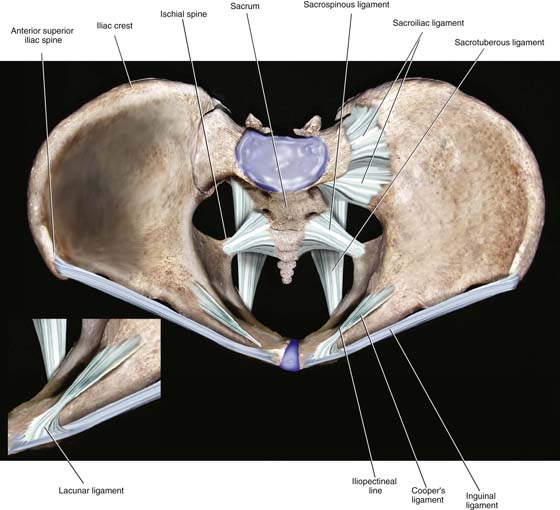

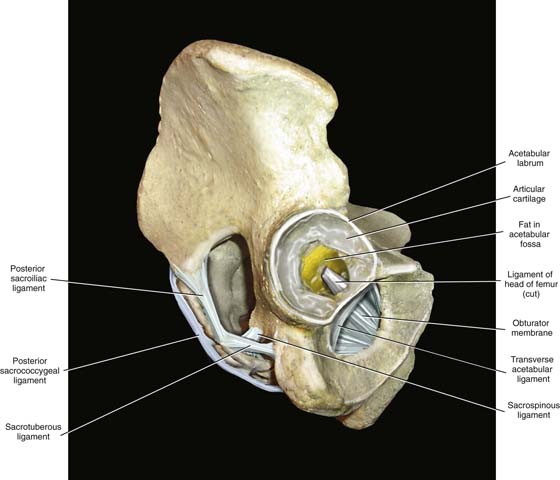

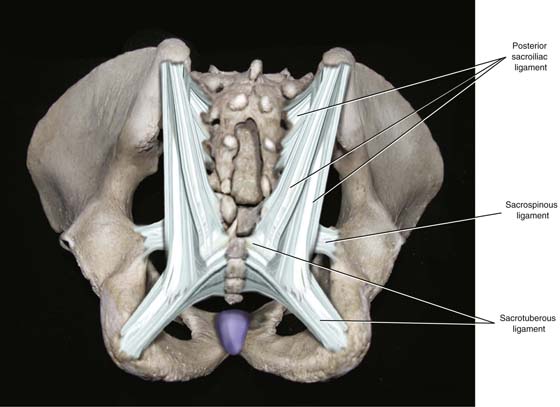

The following ligamentous structures can be observed: Cooper’s ligaments, the sacroiliac ligaments, the symphysis fibrocartilage, the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments, the inguinal ligament, the lacunar ligament, and the obturator membrane (Figs. 1–6 through 1–8). The sacrospinous and Cooper’s ligaments are utilized in pelvic reconstructive surgery, as are the pubic symphysis and the anterior longitudinal ligament (overlying the anterior sacral surface, not sketched). Large vessels and nerves cross from the abdomen to the thigh beneath the inguinal ligament and through the obturator foramen. The lacunar ligament forms the medial abutment of the femoral canal and sometimes is referred to as the pectineal portion, or extension, of the inguinal ligament.

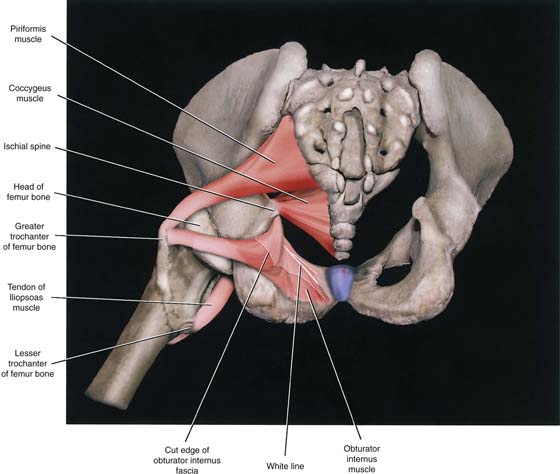

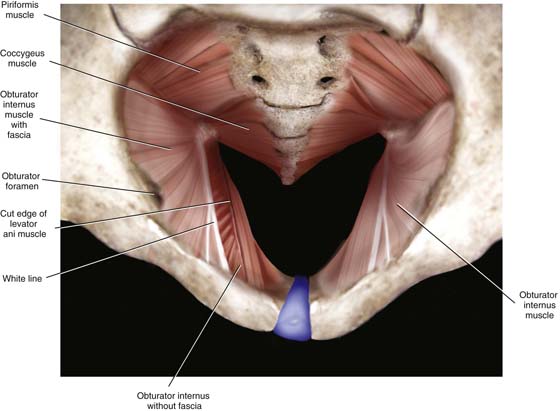

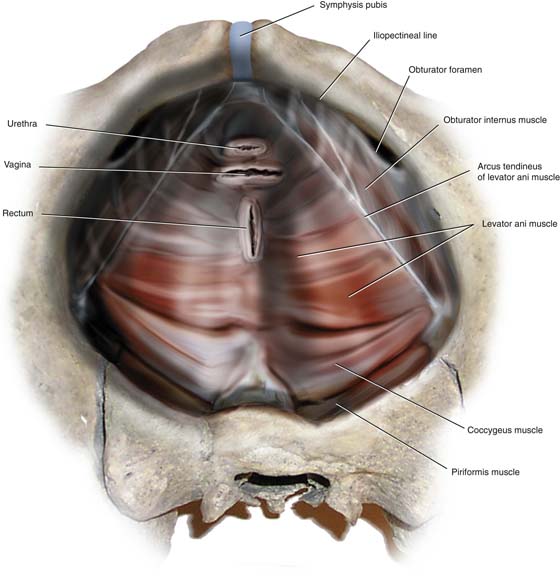

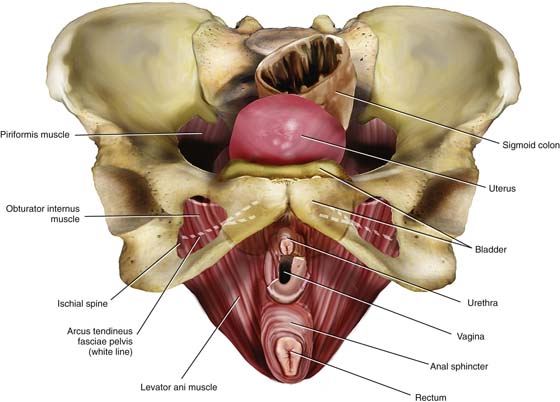

The muscles of the pelvis that have practical and special importance for our discussion are the obturator internus muscle, which constitutes the “pelvic side wall” or “ovarian fossa,” the coccygeus, the piriformis, and the levator ani muscles (Fig. 1–9).

The obturator fascia is a well-defined, tough structure. A particularly thickened portion of the obturator fascia is named the arcus tendineus, or white line (Fig. 1–10). The line stretches from the inner aspect of the ischial spine across the belly of the obturator internus muscle and terminates at the lower margin of the posterior pubic bone (Fig. 1–11).

The levator ani muscle takes its origin from the inferior margin of the pubic bone and the entire arcus (obturator fascia). Several anatomy texts have divided the levator into anterior and posterior portions; however, these subdivisions are artificial and have little practical value (Fig. 1–12). Functionally, the gynecologist can feel this muscle contract by performing a rectovaginal examination and requesting the patient to tighten her muscles as if holding in a bowel movement. At a point 2 cm up (cranial) from the vaginal introitus, the U-shaped muscle is felt along the side and posterior vaginal walls. A similar contraction can be felt posterior to the rectum when the anal sphincter is contracted. Insofar as the rectum is concerned, the levator component can be palpated across the posterior rectal wall. The levator ani in concert with the external sphincter ani squeezes the rectum to narrow the bowel lumen while elevating the anorectum.

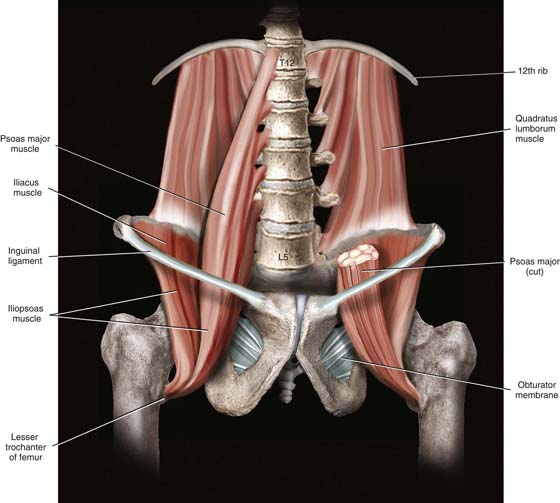

The muscles and ligaments divide notches into windows (foramina). The coccygeus is overlain (deep) by the sacrospinous ligament. The piriformis muscle exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen and is partially overlain (deep) by the sacrotuberous ligament (see Figs. 1–7 through 1–9). Internally, the hollow iliac fossa is covered by the iliacus muscle. At the medial margin and slightly superficial to the iliacus muscles are the psoas major muscles. Together with the iliacus (iliopsoas), the psoas major muscles pass into the thigh beneath the inguinal ligament to insert on the femur (lesser trochanter). Occasionally, the psoas minor tendon may be seen on the anterior surface of the psoas major muscle (Fig. 1–13).

FIGURE 1–1 The pelvic bone consists of the ilium, ischium, and pubis. The ilium is bound to the sacrum at the sacroiliac joints. This anterior aspect of the pelvis shows the pubic arch, symphysis, and obturator foramen via a head-on view.

FIGURE 1–2 This overhead view details the pelvic inlet, which is bounded anteriorly by the pubic symphysis and the pubic tubercle; laterally by the iliopectineal line and the linea terminalis; and posteriorly by the sacral alae and the first sacral vertebra. This view also nicely shows the ischial spines.

FIGURE 1–3 High-power detail viewed through the pelvic inlet shows the sacrum and coccyx. The anterior sacral foramina are distinct, as are the ischial spines and the subpubic arch.

FIGURE 1–4 The posterior view of the pelvis is combined with an outlet “looking-in” perspective. The ischial tuberosity, ischial spine, and greater and lesser sacrosciatic notches are best seen from this vantage point. Posterior sacrum highlights include the sacral hiatus, sacral canal, and posterior sacral foramina.

FIGURE 1–5 This right lateral view depicts the acetabulum, sacrosciatic notches, anterior superior iliac spine, and ischium.

FIGURE 1–6 The inguinal ligament stretches between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. From the latter is reflected the lacunar ligament, which forms the medial boundary of the femoral canal. Cooper’s ligament is a stout structure that clings to the iliopectineal line (see inset). Between the ischial spines and the lateral aspect of the sacrum is the sacrospinous ligament. This ligament also creates the greater and lesser sacrosciatic foramina.

FIGURE 1–7 This side view displays the obturator membrane, as well as the sacrotuberous ligament. The latter begins on the ischial tuberosity and terminates on the lateral margin of the sacrum.

FIGURE 1–8 Posterior view combined with outlet view. The sacrotuberous ligament and the sacrospinous ligament cross.

FIGURE 1–9 The ligaments have been eliminated. Views are through the pelvic outlet. The obturator internus, piriformis, and coccygeus are seen in sharp detail.

FIGURE 1–10 The large obturator internus muscle covered with tough obturator fascia forms the pelvic sidewall. The arcus tendineus, or white line, is produced by a thickened area of obturator fascia. The levator ani muscle arises from the arcus. The cut edge of the levator is shown on the patient’s right side (viewer’s left side). The left levator has been removed. The enclosure of the pelvis is completed by the piriformis and coccygeus muscles.

FIGURE 1–11 This view shows the intact levator ani muscle arising along the length of the arcus tendineus. Note the exposed retropubic space, together with the cut edges of the urethra and vagina.

FIGURE 1–12 Frontal view of the funnel-like levator ani and its relationship to the vulva and superficial muscles of the perineum. The levator arises in part from the inferior margins of the pubic bone. The artist has superimposed the arcus tendineus (dashed white line) onto the obturator internus and pubic bone.

FIGURE 1–13 The large muscles of the retroperitoneum include the psoas major muscle, iliacus muscle, and quadratus lumborum muscle. The psoas and iliacus (iliopsoas) depart the abdomen and enter the thigh beneath the inguinal ligament.

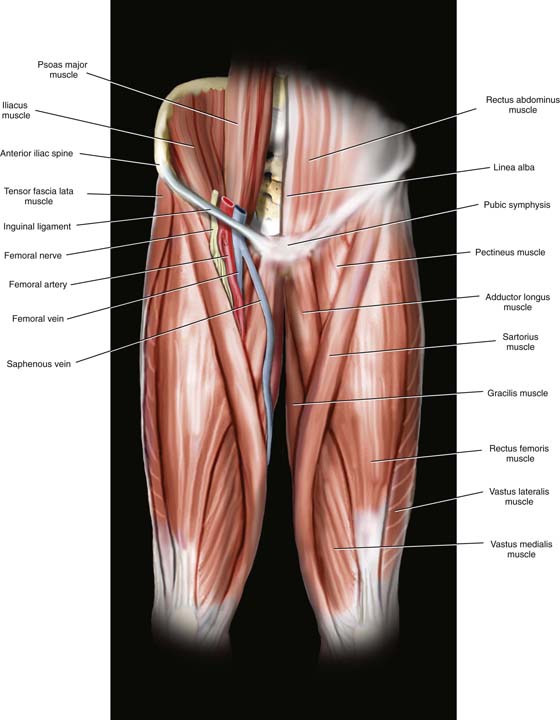

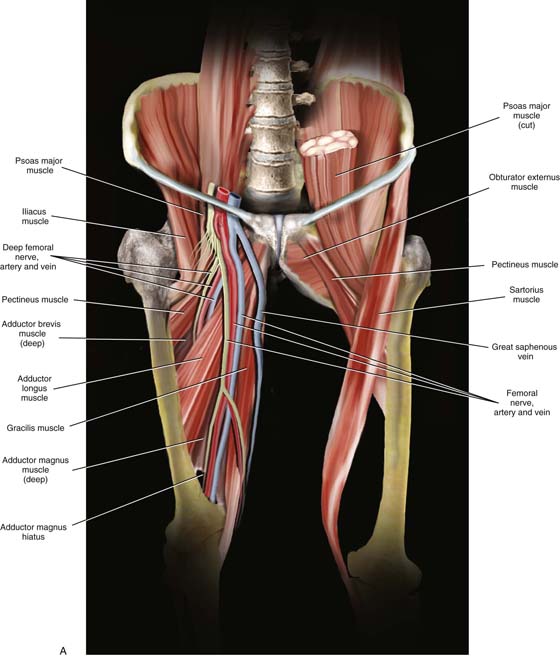

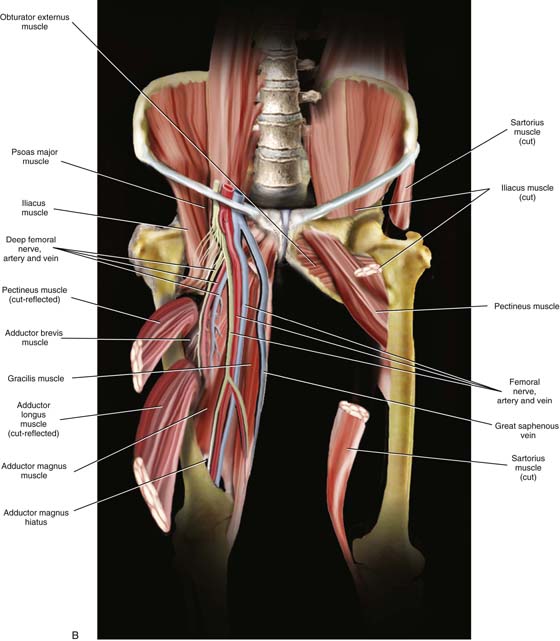

The muscles of the thigh are in many cases relevant to pelvic anatomy. For example, the iliopsoas muscles leave the pelvis beneath the inguinal ligament with accompanying nerves to enter the thigh. The sartorius muscle is detached from the anterior superior iliac spine in radical vulvectomy surgery and transposed to cover the exposed femoral vessels. The gracilis muscle is utilized for pelvic reconstructive surgery as a myocutaneous graft. In addition to the muscles mentioned earlier, the gynecologist should be familiar with the fascia lata, tensor fascia lata muscle, rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, pectineus, and adductor longus muscles (Figs. 1–14 and 1–15A and B).

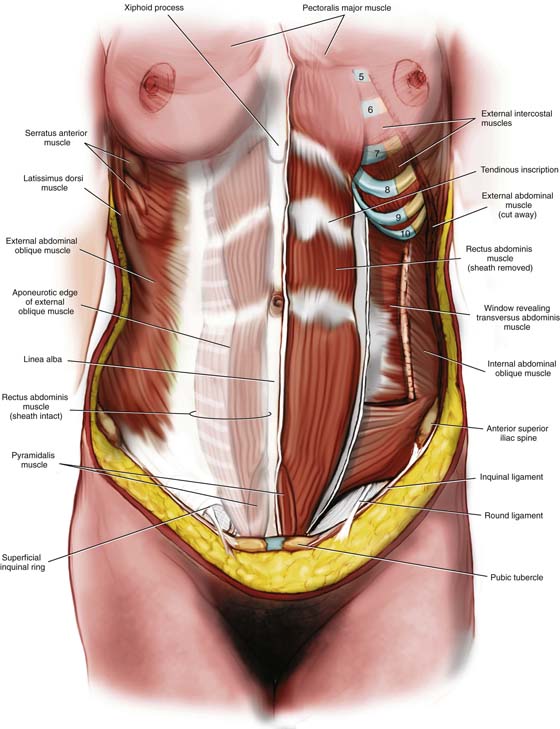

The muscles and fascia of the abdominal wall are discussed in detail in Chapter 7.

However, the schema of the external oblique, internal oblique, rectus abdominis, and transversus abdominis muscles, and inguinal ligament are convenient to view in a single picture (Fig. 1–16).

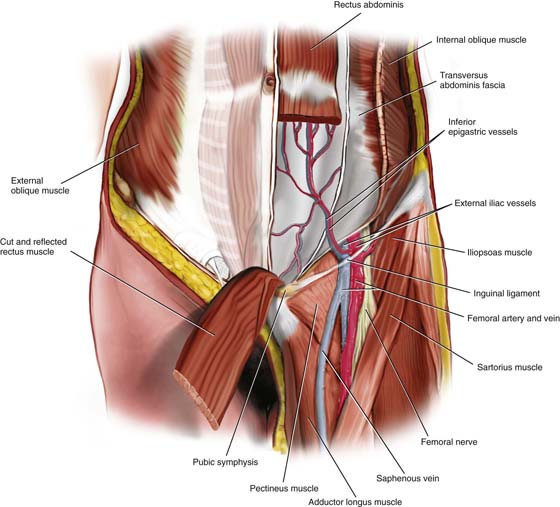

The inferior epigastric vessels are identified crossing the transversus abdominis fascia from their origin in the external iliac vessels. In this drawing, the left rectus abdominis muscle has been divided and the lower muscle belly has been reflected downward (caudal) to show the details of the inferior epigastric vessels, which lie on the post sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle and the transversus fascia. The triangle formed by the inferior epigastric vessels, the inguinal ligament, and the lateral border of the rectus is Hesselbach’s triangle (Fig. 1–17). Indirect inguinal hernias most commonly develop here (Hesselbach’s triangle).

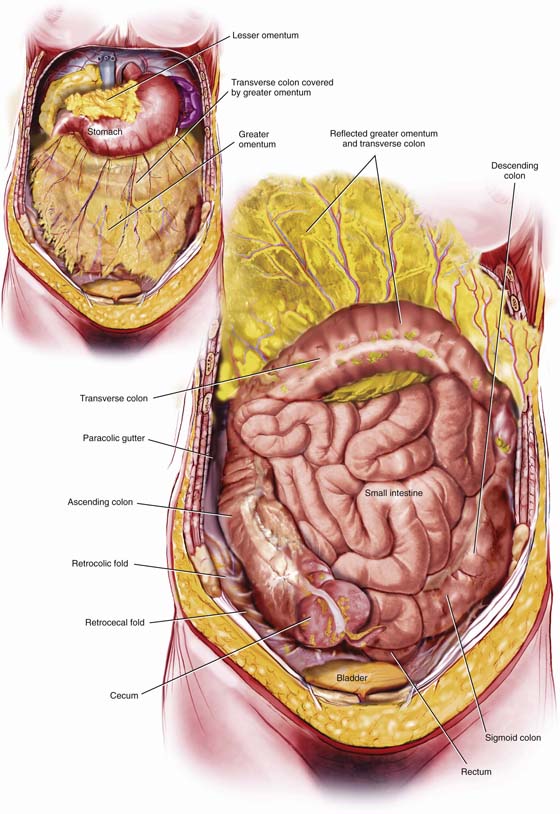

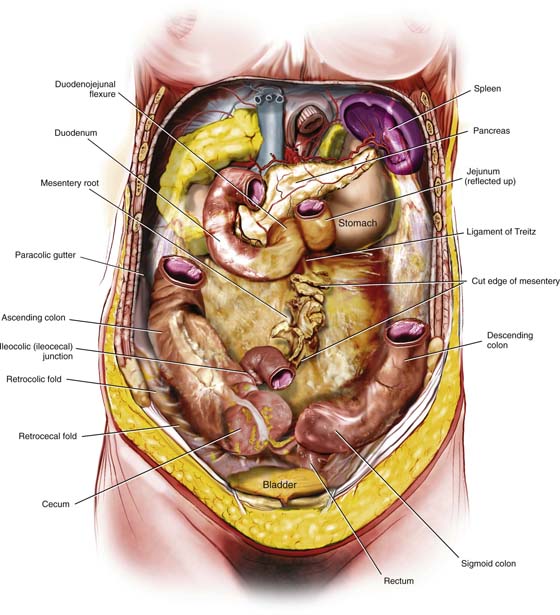

When the lower abdomen is opened, the peritoneal cavity is seen to be filled with intestines. A fat pad, the greater omentum, which is attached cranially to the greater curvature of the stomach and the transverse colon, hangs like an apron over the small and large intestines. Lifting the omentum reveals the large intestine on the periphery surrounding coils of small bowel. The large bowel is anchored normally to the parietal peritoneum along the right and left gutters (Fig. 1–18). The pelvic colon, or sigmoid colon, is a mobile intraperitoneal structure that is suspended by a mesocolon. The pelvic colon ranges from 5 to 35 inches in length and usually lies under the ileum. The rectum is 5 to 6 inches in length. It begins at the third sacral vertebra and hugs the curve of the sacrum, terminating just beyond the end of the coccyx. The rectum is covered only partially with peritoneum, with its upper third having peritoneal covering on the front and sides and the lower two thirds lying largely retroperitoneal (middle third has peritoneum in front only). The large bowel consists of cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and anus.

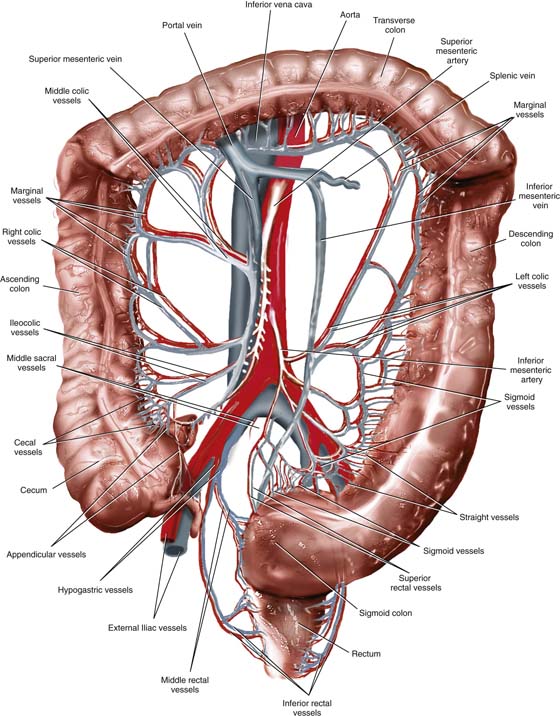

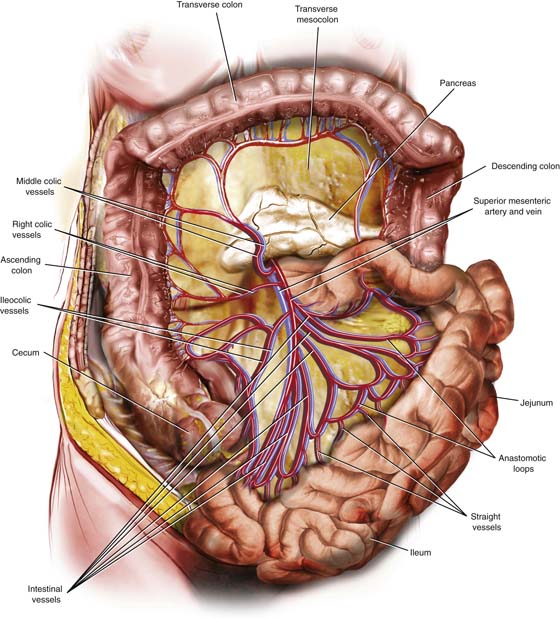

The blood supply to the large intestine emanates from the superior mesenteric artery (right colon and transverse colon) and the inferior mesenteric artery (left flexure, left colon sigmoid colon, upper two thirds of rectum), as well as the internal pudendal artery (anus and lower rectum). The venous drainage is to the hypogastric veins to a smaller extent and to the splenic, or portal, vein to a greater extent (Fig. 1–19).

FIGURE 1–14 Muscles of the thigh are shown, together with their relationships to the saphenous vein, femoral vessels, and femoral nerve. Note that the saphenous vein lies in the fat (dissected away) overlying the adductor longus muscle. The femoral vein is directly superficial to the pectineus muscle. The femoral artery and nerve lie on the iliopsoas muscle(s).

FIGURE 1–15 A. On the cadaver’s right side, the sartorius muscle has been removed, as have the rectus femoris and the vasti. Similarly, the tensor fasciae latae muscle, together with the fascia lata, has been removed to expose the course of the nerves and vessels, as well as the deeper muscles. B. On the cadaver’s left side, the obturator externus muscle, which covers the obturator membrane and foramen, is visible. Note the relationship of the latter to the pectineus muscle and the femoral vessels. Note that the adductor longus has been removed. On the right side, the adductor longus and pectineus muscles have been divided.

FIGURE 1–16 The anterior abdominal wall has been dissected deeply on the patient’s left (viewer’s right) and more superficially on the right. The anterior rectus sheath and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle are prominent on the right. On the left, the external oblique has been cut and largely removed. The internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles are exposed. Note the direction of the external and internal oblique, and of the transversus fibers. The anterior rectus sheath has been opened on the left side, allowing the entire left rectus abdominis muscle to be viewed. The anterior sheath of the rectus is derived only from the fascia of the external and internal obliques below the umbilicus. At this location, the posterior sheath is derived solely from the transversus abdominis muscle.

FIGURE 1–17 The inferior epigastric vessels are important landmarks on the anterior abdominal wall, particularly because of their risk for injury during laparoscopic trocar entry. The artery arises from the lower medial aspect of the external iliac artery. The vein flows into the external iliac vein just cranial to the inguinal ligament. The femoral nerve emerges from within the substance of the psoas major muscle to be exposed directly under the tough inguinal ligament. This view shows the upper portion of the adductor longus, as well as the pectineus muscle. The latter overlies the obturator foramen (canal) and the obturator externus muscle, through which penetrate the obturator nerve plus the obturator vessels (not shown). Note also that the saphenous and femoral veins cross above the pectineus muscle.

FIGURE 1–18 The transversus fascia, which is bound to the anterior parietal peritoneum, is cut and retracted, exposing the greater omentum (inset). When the greater omentum itself is retracted cranially, the underlying large and small intestines dominate the abdominal cavity.

FIGURE 1–19 The blood supply to the right colon emanates from the superior mesenteric vessels. The inferior mesenteric vessels supply the left colon and sigmoid colon. The rectum receives blood from the inferior mesenteric vessels, as well as from branches of the hypogastric vessels. The inferior rectal vessels are branches and tributaries of the internal pudendal vessels. The transverse colon receives dual supply and drainage from superior and inferior mesenteric arteries and veins.

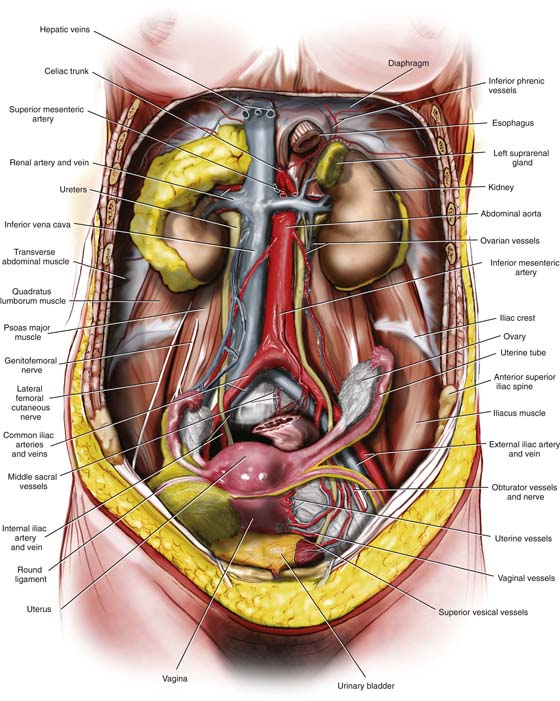

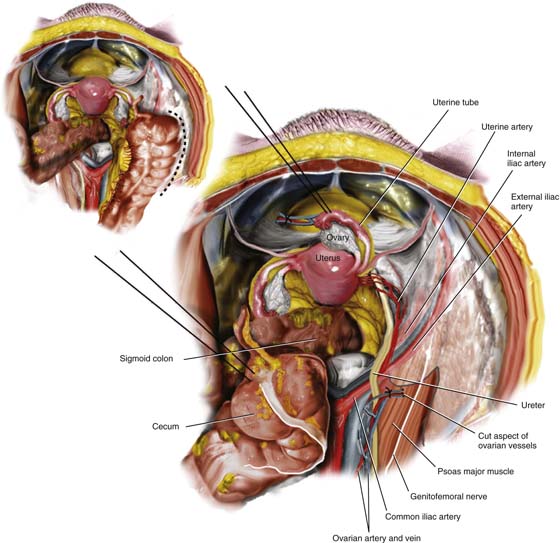

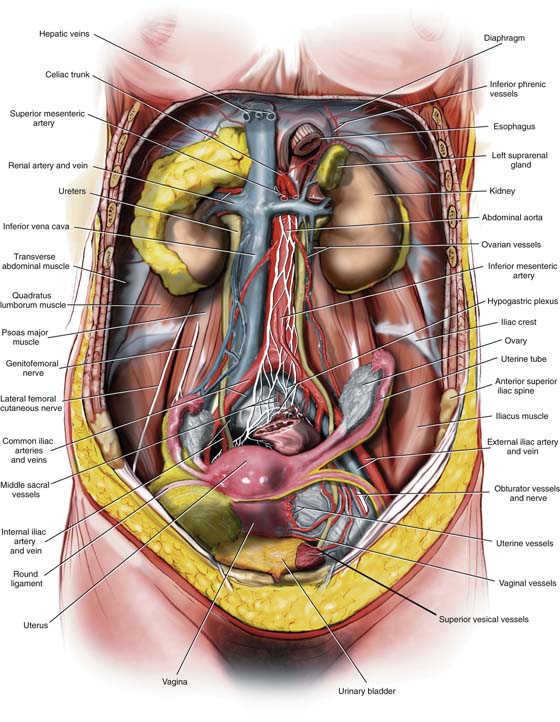

The small intestine measures approximately 20 feet in length. The shortest portion of the small bowel is the duodenum (10 inches), which is closely related to the stomach at its first part and to the jejunum in its fourth part. The major portion of the small intestine consists of jejunum and ileum. The jejunum and ileum are totally surrounded by visceral peritoneum and are anchored to the posterior abdominal wall by a mesentery. The root of the mesentery is 6 to 8 inches in length and extends obliquely from the duodenojenunal flexure to the right colon. The small intestine itself extends from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve (Fig. 1–20). The superior mesenteric artery supplies the small intestine by a series of arcades. Venous drainage occurs via the superior mesenteric vein to the portal vein (Fig. 1–21). The ileum should be carefully examined 2 to 3 feet before the ileocolic junction for the presence of a finger-like projection called Meckel’s diverticulum. This is located on the antimesenteric border. When the small and large bowels are retracted, the uterus, adnexa, and urinary bladder are brought into view (Fig. 1–22). The posterior and lateral parietal peritonei are clearly and similarly viewed but cover the underlying retroperitoneal structures. The peritoneum is incised over the psoas major muscle. The muscle (which may include the psoas minor) is exposed, and the genitofemoral nerve is identified. At the medial margin of the pelvic portion of the psoas muscle is the external iliac artery. Beneath the artery is the larger external iliac vein. The external iliac artery is dissected retrograde and cephalad for identification of the common iliac artery and vein. The latter are marked by the crossover of ovarian vessels coupled with the ureter (Figs. 1–22 and 1–23). The common iliac bifurcation should be identified. The common iliac vein is seen to lie in the crotch formed by the bifurcation of the internal and external iliac arteries. Continuing in a cephalad direction, the common iliac arteries are dissected to their origin at the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta at the L4–L5 interface. Just beneath (caudal to) the aortic bifurcation, the large, blue left common iliac vein crosses the L5 vertebral body. It next tracts beneath the right common iliac artery and joins the right common iliac vein to form the inferior vena cava. The middle sacral artery and vein can likewise be seen on L5–S1 vertebral bodies before descending into the sacral hollow on the sacral vertebrae.

Lateral to the psoas major muscle is the iliacus muscle, over which courses the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. The ureter begins at the renal pelvis. It then courses on the psoas major muscle in company with the ovarian artery and veins. The ureter enters the pelvis by crossing over the common iliac vessels and then assumes a medial position relative to the hypogastric artery (see Fig. 1–23).

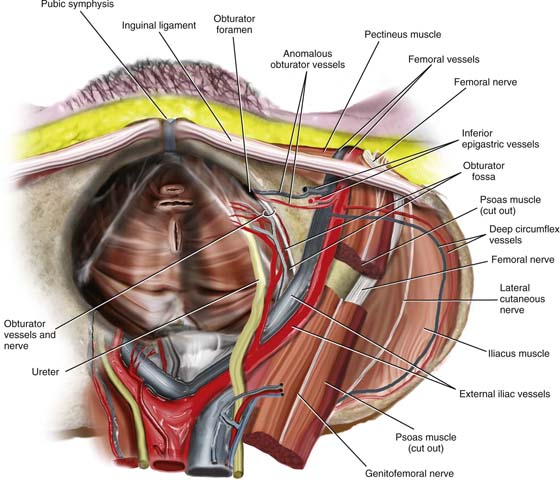

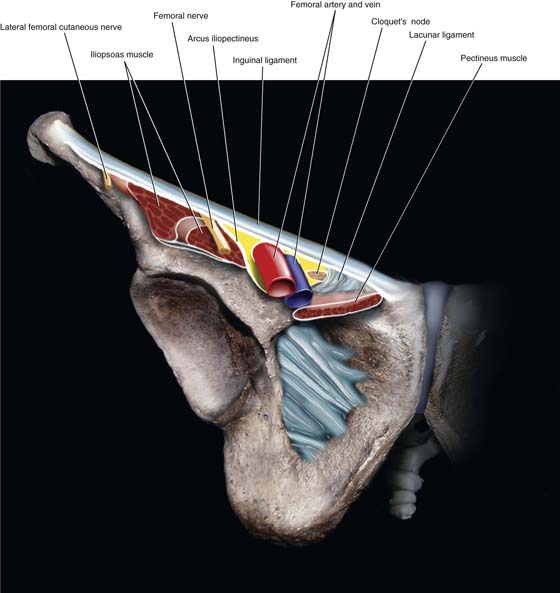

If the pelvic viscera are removed, details of the relationship between the uterine artery and the ureter can be easily appreciated. Similarly, the relationships of the obturator vessels and nerve to the obturator internus muscle and foramen are clear. The external iliac artery and vein cross into the thigh between the inguinal ligament and the iliopectineal line (of the pubic bone). The femoral nerve lies within and is protected by the substance of the psoas major muscle but emerges from this protection as it leaves the abdomen and enters the thigh beneath the inguinal ligament. It is therefore not surprising that compression injuries can happen when women are placed in the lithotomy position with the thigh hyperflexed or severely abducted (Figs. 1–23 and 1–24).

FIGURE 1–20 The normal mesenteric attachments of the intestines are shown in this picture. The small bowel mesentery runs obliquely from left to right. The mesentery starts at the duodenojejunal flexure and ends at the cecum. The right and left sides of the colon are attached by peritoneum to the posterolateral abdominal gutters (left and right). During surgery, inspection of the small intestine should be performed systematically. The entire small bowel should be examined, beginning at the ligament of Treitz and ending at the ileocecal junction.

FIGURE 1–21 The blood supply to the small intestine emanates from the superior mesenteric vessels. The branches of the superior mesenteric vessels are located within the fat of the small bowel mesentery and form a series of arcades as they divide distally. These arcades provide excellent overlapping circulation to the intestine. The collateral circulation is protective in cases of vascular compromise within one of the feeding branches.

FIGURE 1–22 The intestines have been removed. The uterus, adnexa, urinary bladder, ureters, kidneys, and rectum remain. The great vessels, as well as their branches, are exposed. Note that a deeper dissection has been performed vis-à-vis the broad ligament on the left side. The anterior leaf of the left broad ligament has been removed, exposing the course of the uterine and vaginal vessels, as well as the pelvic ureter.

FIGURE 1–23 The ureter descends into the pelvic cavity lying on the psoas major muscle. It is lateral to the inferior vena cava. The ureter crosses over the common iliac vessels just cranial to the iliac bifurcation. It is medial to the hypogastric artery, the obturator neurovascular bundle. At the level of the cardinal ligament, the uterine vessels cross over the ureter. This drawing illustrates the relationships of structures crossing from the abdomen beneath the inguinal ligament into the thigh. The genitofemoral nerve lies on the psoas major muscle. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve lies on the iliacus muscle. The femoral nerve (see cutaway) is buried within the substance of the psoas major and emerges from the muscle just above where it crosses under the inguinal ligament.

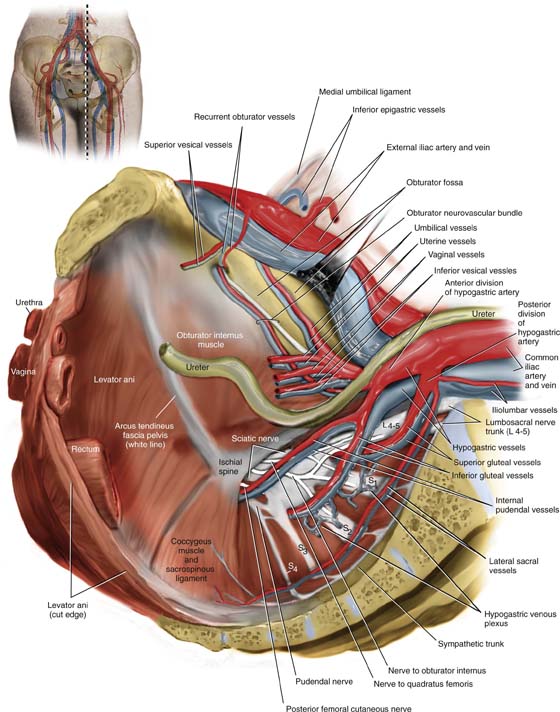

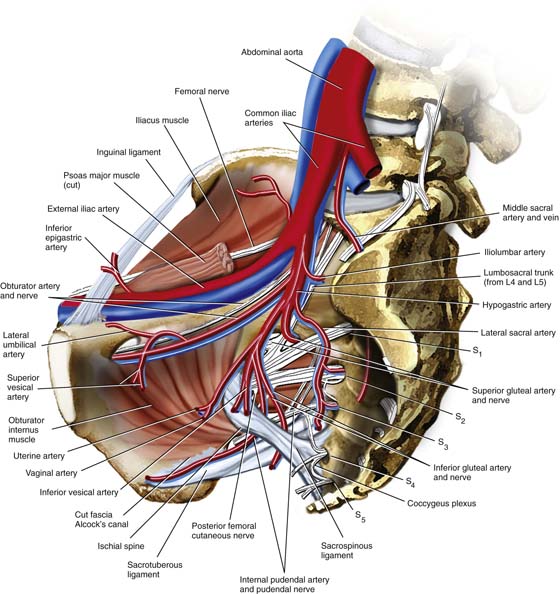

FIGURE 1–24 Sagittal section through the pelvis (see inset). The muscles enclosing the pelvis include the sidewall muscles, that is, the obturator internus, coccygeus, and piriformis. The white line, or arcus tendineus, stretches between the ischial spine and the lower margin of the pubic bone. The levator ani takes its origin from the thickened obturator internus fascia (the arcus tendineus), as well as from the lower margin of the pubic ramus. The bifurcation of the common iliac vessels is seen. The internal iliac, or hypogastric, vessels supply the pelvic viscera via several branches and tributaries. The hypogastric artery divides into a superior posterior division and an inferior anterior division. From the posterior division, the following emanate: superior gluteal vessels, lateral sacral vessels, and iliolumbar vessels. Anterior division branches include lateral umbilical, superior and inferior vesical, obturator, uterine, and vaginal. Terminal branches of the anterior division include the inferior gluteal and internal pudendal vessels. The posterior division of the hypogastric artery will lead the dissector to the sacral nerve roots and the sciatic nerve. The obturator neurovascular bundle is best exposed by retraction of the external iliac vein. The lateral umbilical vessels ascend the anterior abdominal wall supported superficial to the external iliac vessels on either side of the urachus (not shown here).

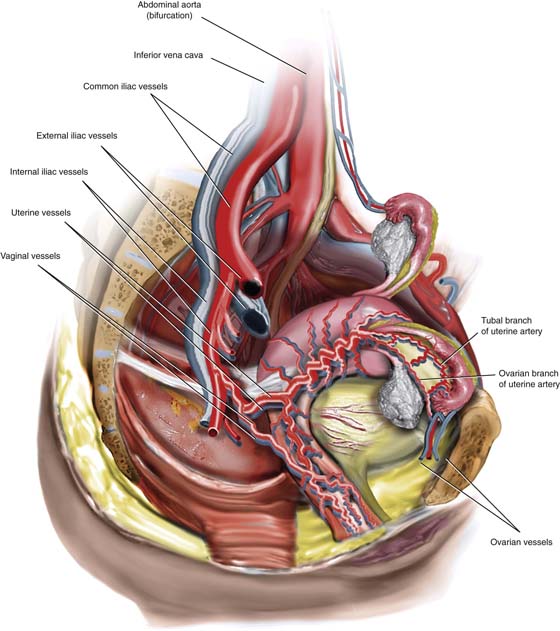

The sagittal cut shows details of the bony pelvis and musculature but mainly the pelvic blood supply (Figs. 1–24 and 1–25). After bifurcating from the common iliac artery, the hypogastric artery (internal iliac artery) itself immediately splits into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior division supplies most of the pelvic viscera. The posterior division branches to form the superior gluteal, lateral sacral, and iliolumbar vessels. Following the posterior division down into the depths of the pelvis will lead to the sacral nerve roots, which together constitute the huge sciatic nerve. A vein retractor is placed carefully under the external iliac vein; an upward pull will expose the obturator fossa (see Fig. 1–23). When the fat is cleared from this space, the lateral margins of the fossa are seen and consist of the pubic bone and the obturator internus muscle. Several branches of the anterior division of the hypogastric artery can also be identified. These include the lateral umbilical vessels, the superior vesical vessels, and the obturator vessels. Variations in these vessels are common, for example, anomalous obturator vessels (see Fig. 1–23). The terminal branches of the anterior division are the internal pudendal and inferior gluteal vessels. The uterine and vaginal vessels may come off via a common trunk or separately (see Fig. 1–25).

The internal pudendal artery actually leaves the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen then reenters by crossing behind and under the sacrospinous ligament to reenter the pelvis via the lesser sciatic foramen. The neurovascular bundle transverses the lowest portion of the obturator internus muscle and fascia (Alcock’s canal), just medial to the ischial tuberosity (see Fig. 1–25).

The relationship of the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments to major pelvic vessels and nerves is of important clinical value in that surgery performed in this area must be precise to avoid injury to those vital structures. As can be readily observed, inaccurate placement of stitches could damage the superior or inferior gluteal vessels (or both), as well as the sciatic nerve (see Fig. 1–25).

Because some urethral tape-suspensory surgeries utilize the obturator foramen, the precise location of the obturator vessels and nerves is required to avoid injury to these structures. For operations involving the presacral space, knowledge of the location of the middle sacral vessels and emerging sacral nerve roots is essential (see Fig. 1–25).

Exposure of the pelvic ureter is a required skill for anatomists as well as for gynecologic surgeons. Any technique to accomplish the goal of ureteral identification should be easily performed with a low risk for bleeding or ureteral injury.

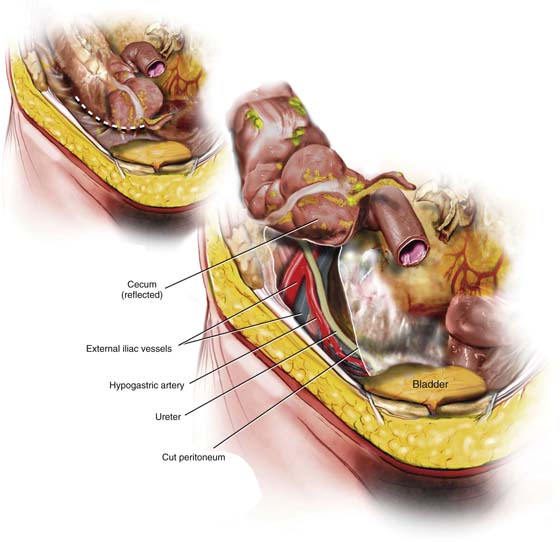

On the right side, the surgeon or anatomist should grasp the cecum, elevate it, and place light traction toward the left. The peritoneum along the right gutter is incised (dashed line, Fig. 1–26), which in turn produces great mobility. As the cecum is freed, the psoas major muscle comes into view, as do the right ureter and common iliac vessels. Next, the medial edge of the peritoneum, to which the ureter is closely attached, is grasped with fine forceps and placed on traction (see Fig. 1–26). The ureter can be easily separated from the peritoneal edge with a dissecting scissors, using a closed-push, open-spread technique. Thus, the ureter can be freed from the pelvic brim to the point where the uterine arteries cross over the ureter (Fig. 1–27). The surgeon should be aware that the ovarian artery and veins are in the same peritoneal fold as the ureter at the crossover of the common iliac artery (see Fig. 1–22). The ovarian pedicle and the ureter should be separated from one another by sharp dissection. Only after both structures are separately identified should the ovarian vessels be clamped, cut, and ligated. If short-cuts are taken in accurately identifying and securing the anatomic landmarks, ureteral injury will be inevitable.

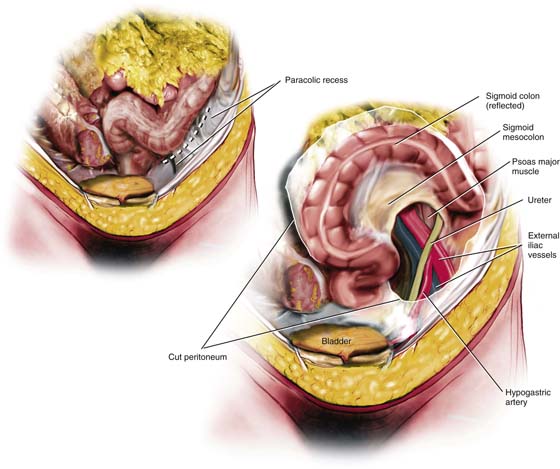

The left ureter is identified by similar measures to those described for the right side of the pelvis. However, on the left, the sigmoid colon is grasped and pulled to the right, thereby placing tension on the left peritoneal attachment. Retroperitoneal entry and exposure are produced by incising the peritoneum along the left paracolic gutter (dashed line, Fig. 1–28). Once this is done and the loose areolar tissue dissected, the psoas major muscle comes directly into view. The muscle crosses the incision line in a perfect perpendicular direction. The left iliac vessels are identified, and medial to these is the left ureter. The left ureter proceeds deep into the pelvis to the left and in the bed of the sigmoid colon.

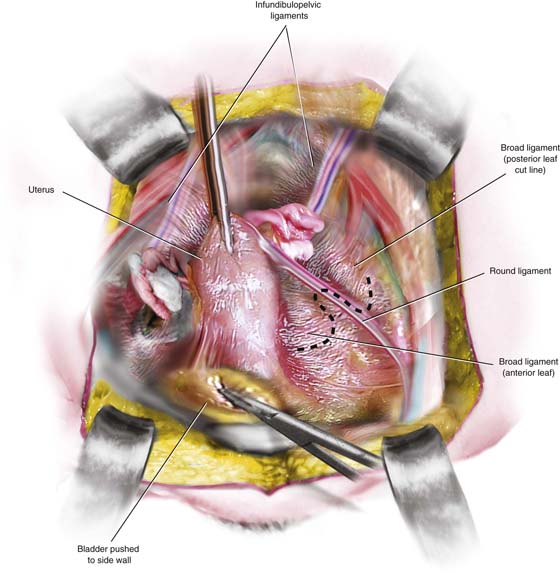

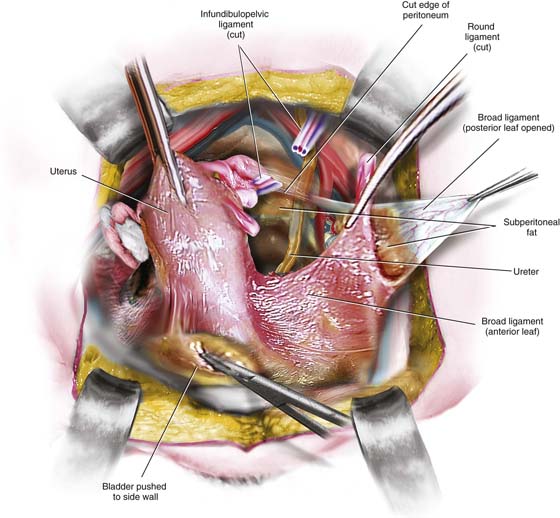

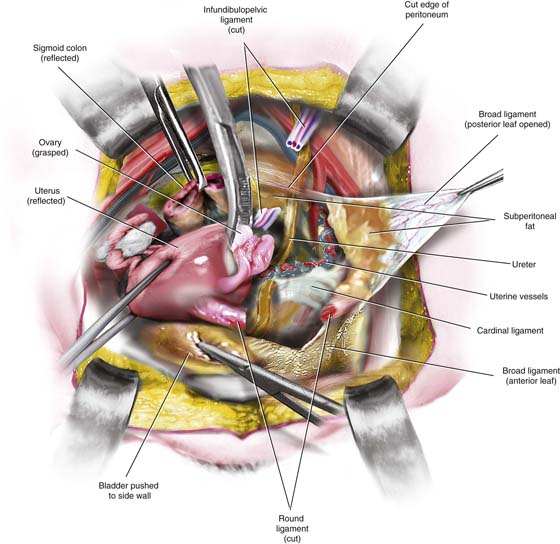

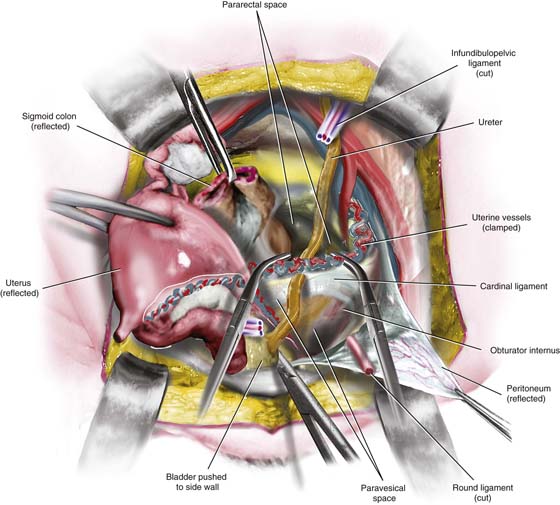

As the right and left ureters descend inferiorly and caudally into the depths of the pelvis, they also vector medially. At the point where the ureters encounter the uterus, they are less than a centimeter from the uterosacral ligaments. The ureters enter the substance of the cardinal ligaments at the point where the uterine vessels cross above and the vaginal vessels cross below (Fig. 1–29). To expose the lower ureter, the cardinal ligament must be dissected, that is, the ureter will be unroofed. This dissection is sharply performed and requires knowledge of the sense of direction that the ureter is taking through the cardinal ligament. A tonsil clamp creates an oblique tunnel over (superiorly and anteriorly) the ureter. The clamp is spread, thereby enlarging the space; then the cardinal ligament on each side is clamped and cut, thereby exposing the ureter as it enters the bladder, as well as securing the uterine vessels as they cross above the ureter (Figs. 1–30 through 1–33).

FIGURE 1–25 Sagittal section with several pelvic muscles removed to show the inguinal, sacrospinous, and sacrotuberous ligaments. Note the internal pudendal artery and the pudendal nerve leaving the pelvis via the superior sacrosciatic foramen and reentering via the inferior sacrosciatic foramen. At the reentry point, the pudendal neurovascular bundle enters a fascial canal created within the lowest portion of the obturator internus muscle—Alcock’s canal. Note that the femoral nerve (within the substance of the psoas major muscle) emerges from within the psoas major muscle as it passes exposed beneath the inguinal ligament. The huge sciatic nerve (L4, L5, S1, S2, S3) leaves the pelvis over the piriformis muscle via the greater sacrosciatic foramen. Note that the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments form the sciatic foramina from the sacrosciatic notches.

FIGURE 1–26 A quick, safe, and relatively easy technique for entering the retroperitoneal space is illustrated in this drawing. The cecum is grasped, elevated, and pulled to the left. The peritoneum (parietal) supporting the cecum to the right abdominal gutter is cut (dashed line). The cecum is mobilized upward. The underlying psoas major muscle, common iliac vessels, and ureter are brought into clear view. Note that the ovarian vessels have been removed in the drawing. This view is oriented from below in a cranial direction. The ovarian vessels have been removed.

FIGURE 1–27 Exposure of the retroperitoneal space on the right by incising the lateral peritoneal supports, the cecum, and ascending colon (dashed line) allows the large bowel to be mobilized toward the left. The right common iliac vessels, the vena cava, and the ureter are brought into view. The genitofemoral nerve is seen on the surface of the psoas major muscle. The uterine vessels are shown crossing the ureter at the level of the cardinal ligament. Note the right ovarian vessels cut and ligated but overlying the ureter on the right side. This view is oriented to allow observation of the field from above, looking caudally.

FIGURE 1–28 The technique for exposure of the retroperitoneal space on the left side is shown. The sigmoid colon is grasped, elevated, and pulled to the right. The lateral peritoneal attachments of the sigmoid and descending colon are cut along the left gutter (dashed line in inset), permitting free mobilization of the large bowel. The left psoas major crosses the sigmoid colon at a perfect 90° angle. The left common iliac vessels and the left ureter are brought into view. The left ovarian vessels, which overlie the ureter, have been removed in this drawing. The ovarian vessels (infundibulopelvic ligament) are not shown in this drawing (i.e., they have been removed).

FIGURE 1–29 This view from the back shows the course of the ureters as they descend deeply into the pelvis. Note that the ureters are closely approximated to the medial-lying hypogastric arteries. The ovarian vessels have been pulled laterally to separate them from the ureters and to better expose the ureters. The cardinal ligaments have been exposed by incising the posterior leaf of the broad ligament. Note the uterine vessels above and the vaginal vessels below as the ureters curve inward during their short journey through the cardinal ligaments. The infundibulopelvic ligament (ovarian vessels) has been retracted laterally and away from the ureters in this picture. In actual dissection, the ovarian vessels and the ureters cross over the common iliac vessels very close to one another.

FIGURE 1–30 The uterus is pulled upward by means of a fundal clamp. This technique places the broad ligament on tension and makes it easier to see. The dashed line shows how an incision will be made through the top of the ligament and extended to open the anterior and posterior leaves.

FIGURE 1–31 The left broad ligament has been opened. The loose areolar tissues between the leaves have been dissected to expose the deeply situated left ureter.

FIGURE 1–32 The ureter is further dissected to expose the uterine arteries crossing over the ureter.

FIGURE 1–33 The uterus is rotated to stretch the ureter and uterine vessels. Tonsil clamps are placed on the uterine artery to divide it above the point where the ureter crosses under it. The entire course of the ureter is visible.

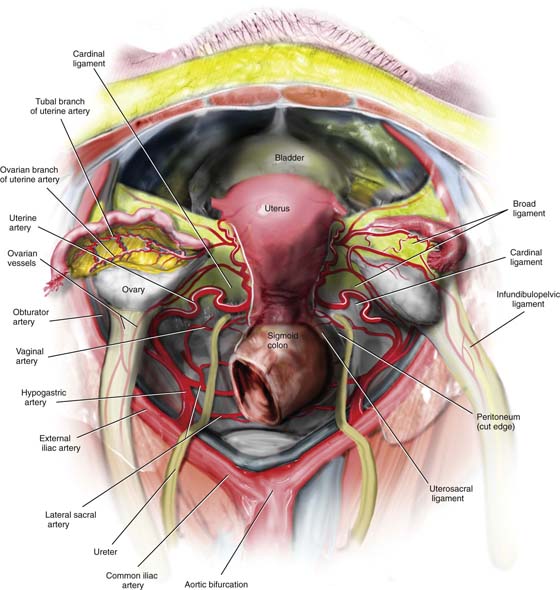

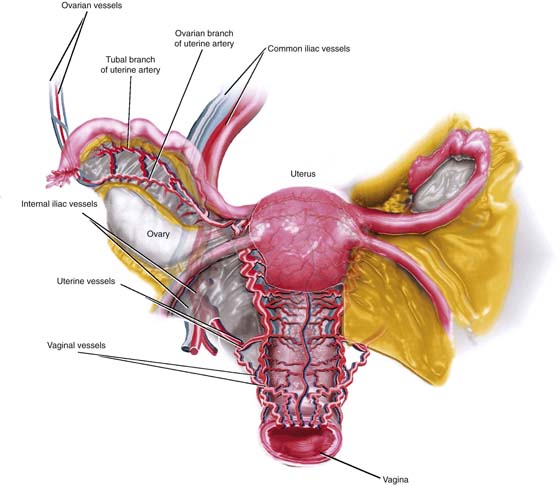

The blood supply to the uterus is generous. The uterine artery is a major branch of the anterior division of the hypogastric artery. The uterine artery in the vicinity of the junction of the cervix and uterine body splits into ascending and descending branches. The former is a coiled vessel that makes its way up the side of the uterus beneath the round ligament to the area between the junction of the tube, utero-ovarian ligament, and upper uterine corpus. At that point, the uterine and ovarian arteries anastomose (Figs. 1–34 and 1–35).

Just before the uterine artery bifurcation, the vaginal artery may come off a common trunk, with the uterine artery. Alternatively, the vaginal artery may arise directly as a branch of the main hypogastric artery. Several sources of collateral circulation may be observed relative to the pelvic viscera. Although the hypogastric artery may be bilaterally ligated, blood flow to the pelvic organs continues via these collaterals. The inferior mesenteric and ovarian vessels are examples of collaterals via middle and inferior hemorrhoidal connections, as well as between ovarian and uterine branches of tubo-ovarian vessels (see Figs. 1–34 and 1–35).

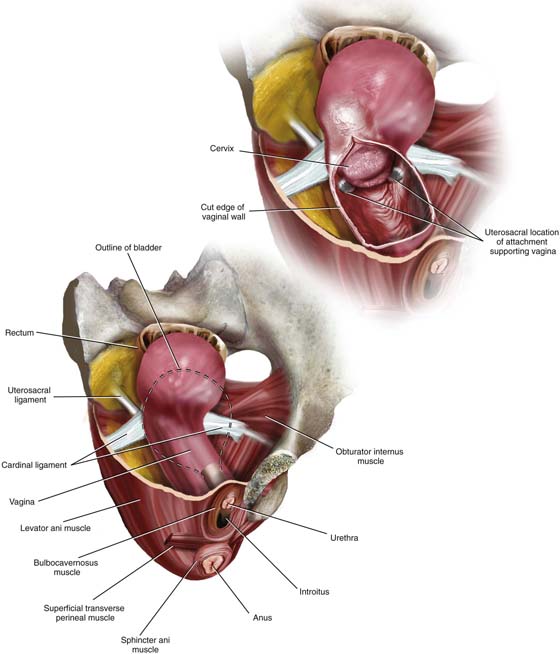

The vagina is a musculoepithelial tube extending from the level of the external genitals to the cervical portion of the uterus. It is a reproductive conduit in all respects, connecting the external environment to the internal genitalia. Anatomically, the vagina is anchored caudally and directly at the introitus by the levator ani muscles and bulbocavernosus muscles. Indirectly, other structures may contribute to the caudal vaginal support; these include the external sphincter ani, superficial transverse perineal muscles, and the perineal membrane. The anterior and posterior vaginal walls share fascial support in a manner analogous to that in unibody automobile construction with the bladder/urethra and rectum/anus. The vagina is intimately close to the bulb of the vestibule and clitoral apparatus. At the upper (cranial) end, the vagina shares support with the same structures that support the uterus. Specifically, these are the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments (Fig. 1–36).

Between the two terminals, the vagina is relatively flexible and may be easily freed from surrounding fatty tissue and loose fascia. Anteriorly and posteriorly, the potential spaces are the vesicovaginal and rectovaginal, respectively. Laterally, on either side, the free space may be identified by cutting medially to the bulbocavernosus and levator ani muscles and developing the space along the outer wall of the vagina.

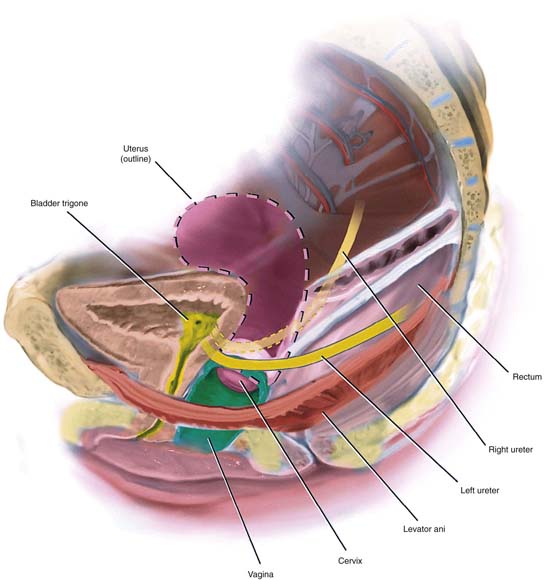

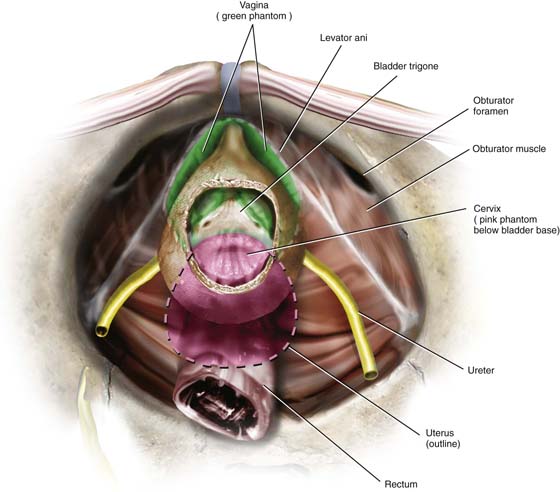

The relationship of the lower ureters to the uterosacral ligaments and anterolateral vagina is important in that injuries to the ureters are most likely to occur in areas where there is close proximity of structures such as these. Similarly, the cervix uteri and anterior fornix of the vagina are intimately close to the bladder base (trigone and interureteric ridge). Because multiple operations (e.g., hysterectomy [vaginal and abdominal], cervical suture, colposuspension, transvaginal urethral suspensions, culdoplasty) are performed in the area, knowledge of the anatomy of the vagina, ureters, and bladder is vital for avoiding unintended iatrogenic injury (Figs. 1–37 and 1–38).

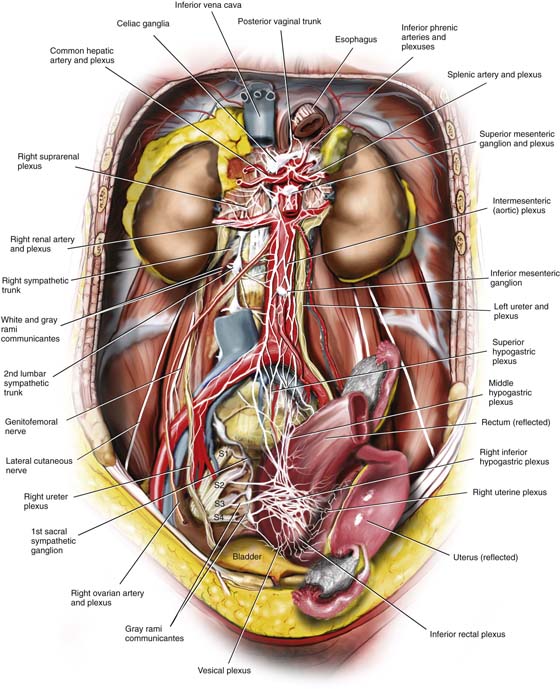

The hypogastric plexus is anterior to the lower aorta and enters the presacral space from above over the retroperitoneal fat anterior to the left common iliac vein and middle sacral vessels and to the right of the inferior mesenteric vessels. As the plexus descends into the hollow of the sacrum, it typically splits into right and left divisions. The inferior hypogastric plexuses join other nerves to form the pelvic plexuses, which in turn are named for the organ with which they are associated. The hypogastric plexus is a conduit for autonomic nerves, as well as visceral pain fibers. The pelvic plexuses contain visceral and parasympathetic fibers from sacral roots 2, 3, and 4 and sympathetic fibers via the sympathetic trunks and hypogastric plexus (Figs. 1–39 and 1–40).

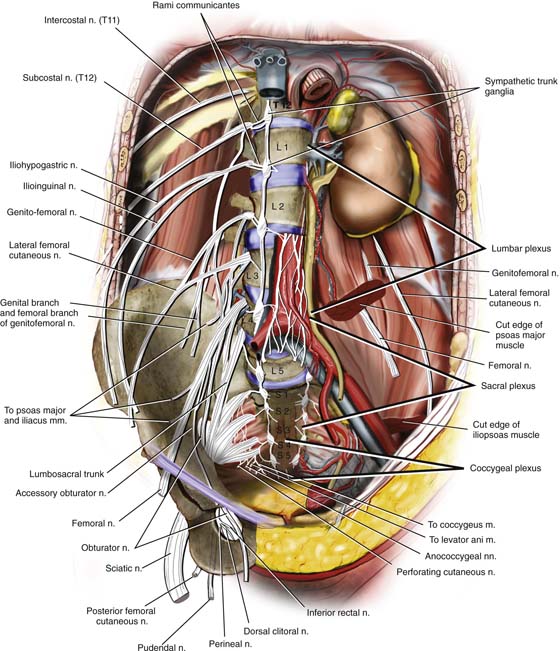

Several of the large nerves of the pelvis and inferior extremity originate deep in the retroperitoneum of the lower abdomen and pelvis. The plexuses include lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal (Fig. 1–41). The lumbar plexus is buried deeply beneath the substance of the psoas major muscle. The subcostal nerve sends a branch to the first lumbar nerve and should be considered part of the plexus. The following nerves emanate from the lumbar plexus (see Fig. 1–41):

1. Iliohypogastric

2. Ilioinguinal

3. Genitofemoral

4. Lateral femoral cutaneous

5. Obturator

6. Femoral

The lumbosacral trunk consists of the anterior ramus of the fifth lumbar nerve joined to the descending branch of the fourth lumbar nerve. The lumbosacral trunk and the anterior rami of sacral nerves 1, 2, and 3, as well as the upper fourth sacral anterior root, form the sacral plexus. The sciatic nerve consists of fibers from the lumbosacral trunk, as well as sacral roots 1, 2, and 3. The pudendal nerve springs from the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves and leaves the pelvis between the piriformis and coccygeus muscles (see Fig. 1–41).

The following additional nerves have their origin in the sacral plexus:

1. Superior gluteal

2. Inferior gluteal

3. Posterior cutaneous nerve

4. Nerve to quadratus femoris

5. Nerve to obturator internus

6. Perforating cutaneous nerve

7. Perineal branch of fourth sacral nerve

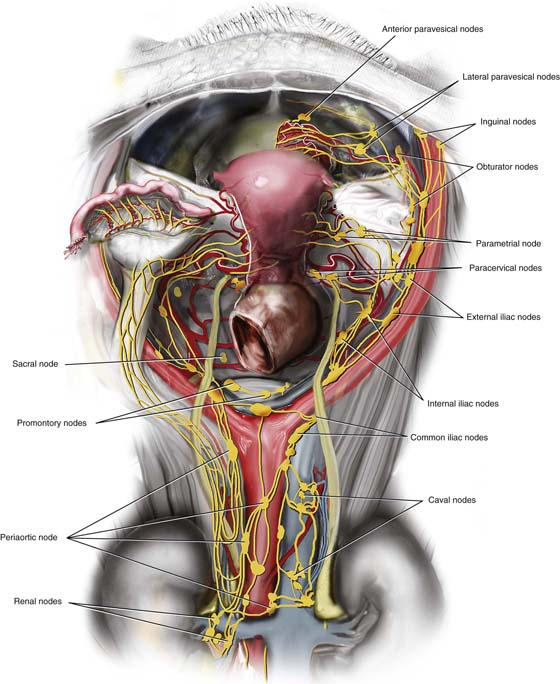

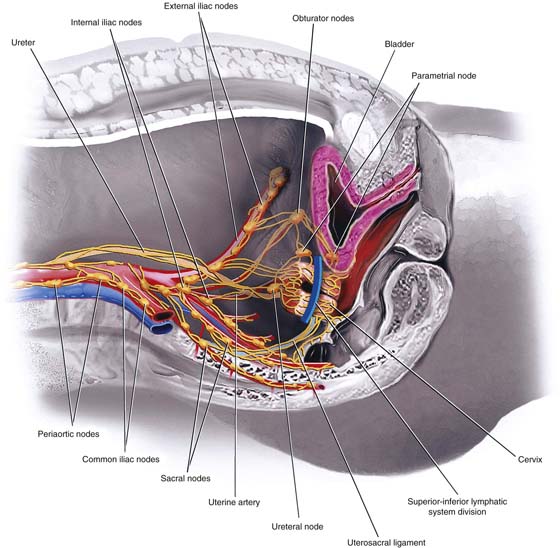

The lymph channels of the pelvis generally follow the course of the major blood vessels. The pelvic lymph nodes are located at various vascular and nonvascular sites (Fig. 1–42).

FIGURE 1–34 This illustration details the blood supply to the uterus and upper half of the vagina. The anterior division of the internal iliac, or hypogastric, artery branches to give off the uterine and vaginal arteries. Not uncommonly, these vessels emanate from a common arterial trunk (as illustrated here). The uterine artery passes obliquely through the lower portion of the broad ligament to reach the upper portion of the uterine cervix at a point where cervix and corpus fuse. The uterine artery divides to form an ascending branch, which heads up the side of the uterus to the level of the fundus, and a descending or cervical branch, which heads downward toward the cervix and its ultimate anastomosis with the vaginal artery. Plentiful cross-uterine anastomoses occur where the ascending branch of the uterine artery reaches the point at which the oviduct joins the fundus of the uterus. It anastomoses with the ovarian and tubal branches of the ovarian artery.

FIGURE 1–35 Sagittal view of the uterine artery and vein. Note the close relationship of the bifurcation of the uterine vessels and the uterosacral ligaments. The main trunk of the artery is just lateral to the point where the uterosacral ligament attaches to the uterus. The anastomosis between the descending branch of the uterine artery and the vaginal artery is clearly seen. The ureter has been excluded from the drawing on the right side.

FIGURE 1–36 This three-dimensional drawing shows the relationships of the vagina to other structures in the pelvis. The lower figure also shows the superimposed outline of the urinary bladder relative to the vagina. The upper vagina shares support with the uterus and bladder. Principally, this consists of the deep cardinal ligament and, to a lesser extent, the uterosacral ligaments. Note in the upper illustration the schematically drawn location of the portion of the uterosacral ligaments that attach to the vagina.

The lower vagina is clearly supported by the levator ani muscle, the anal sphincter, and the deep vascular structures located beneath the bulbocavernosus muscle, as well as by the commonly shared connective tissue, smooth muscle, and vessels found in the tissues between the rectum and vagina, and, likewise, between the bladder and vagina. Between these anchors, the lateral vaginal wall is not attached and opens into fat-filled paravaginal space. If the lateral wall is cut and the fat being dissected is removed, the anatomist will be looking into a retropubic (extraperitoneal) space filled with fat. If the fat is cleaned away, the obturator internus muscle is visible.

FIGURE 1–37 Sagittal view of the ureters and urinary bladder shown in relation to the vagina (green) and the uterus (dark pink). Note that the bladder base and trigone are closely applied to the anterior vaginal fornix and to the cervix, as well as to the cervicocorpal junction. The ureters cross the anterolateral aspects of the vaginal fornices just before entering the bladder wall. Sutures placed too high into the vagina during a colposuspension operation could conceivably injure the ureter(s).

FIGURE 1–38 This full frontal view of the bladder with an anterior window of tissue excised shows the trigone and interureteric ridge. Beneath the bladder posteriorly lies the (phantom) uterus and cervix, which are pink. Note that the bladder base overlies the cervix and vagina (green). The phantom vagina is seen because this stylized drawing has presumed to make the posterior wall of the bladder selectively transparent. Again, note that a misplaced and high suture placed in the vagina during a colposuspension could injure the terminal ureter. The ureters must traverse the tissue above the anterolateral vaginal fornices to reach the bladder.

FIGURE 1–39 Full view of the abdomen showing the hypogastric nerve plexus descending into the pelvis superficial to the aorta and the left common iliac vein. Below the bifurcation, the hypogastric nerve is embedded within the fat of the presacral space. The hypogastric nerve plexus is sometimes referred to as “the presacral” nerve.

FIGURE 1–40 The pelvic viscera are innervated via the autonomic nervous system, which can be seen as a somewhat amorphous concentration of nerve fibers and ganglia. These collections are named on that basis of the organ(s) they supply, for example, vesical, uterine. The sympathetic fibers originate in the thoracic and lumbar segments of the spinal cord and reach the pelvic organs via the hypogastric plexus. In this illustration, the superior, middle, and inferior hypogastric plexuses are shown. The parasympathetic contribution joins the inferior hypogastric plexus via the pelvic nerves (sacral nerve roots 2, 3, and 4). The picture shows the pelvic nerves and the inferior hypogastric plexus joining in the right uterine plexus.

FIGURE 1–41 The lumbar and sacral plexuses shown here contribute efferent and afferent fibers to the major somatic nerves of the pelvis and inferior extremity. The lumbosacral trunk and the first four sacral nerves form the sacral plexus.

FIGURE 1–42 The lymphatic vessels and nodes of the pelvic viscera are shown. Note the relationship of the primary cervical drainage to the paracervical lymph nodes located at the point where the uterine vessels cross above the ureter. The parametrial lymph vessels draining the corpus and fundus drain into nodes located in the obturator fossa and the internal iliac nodes. The ovarian lymph vessels drain along a course following the ovarian veins to periaortic, caval, and renal lymph nodes. Lymphatics along the round ligament drain into groin lymph nodes.

From the cervix, channels drain into a series of primary nodes:

1. Parametrial nodes at the junction of the corpus and cervix located within the fat of the broad ligament.

2. Paracervical nodes located at the point where the uterine artery crosses over the ureter.

3. Obturator nodes located within the fat of the obturator fossa surrounding the obturator nerve and blood vessels.

4. Internal iliac nodes located along the hypogastric vein and in the crotch between the divisions of the common iliac artery.

5. External iliac nodes located between the artery and the vein.

6. Sacral nodes located along the middle sacral vessels and the sacral promontory and the lateral margins of the sacrum.

Secondary lymph nodes consist of the following:

A. The common iliac lymph nodes, which lie on both lateral and medial surfaces of the iliac arteries and veins.

B. The periaortic nodes, which lie on the anterior and lateral surfaces of the aorta from the bifurcation to the diaphragm.

C. The inguinal lymph nodes, above and around the femoral vein and artery and the great saphenous vein.

If one were to draw a transverse line through the middle of the cervix at the vaginal attachment, it would divide the lymphatic drainage into superior and inferior segments, with the former draining the upper cervix and lower uterus into the hypogastric nodes, and the latter draining the lower cervix and upper vagina into the lateral sacral nodes (Fig. 1–43).

Interiliac nodes are located at the bifurcation of the common iliac arteries and along the external and hypogastric vessels. Uterine fundal lymphatics may drain along the round and inguinal ligaments to the superficial and deep inguinal nodes. Similarly, the lymph vessels that drain the ovaries follow the ovarian arteries and veins, hence to the pericaval, periaortic, and right and left renal nodes.

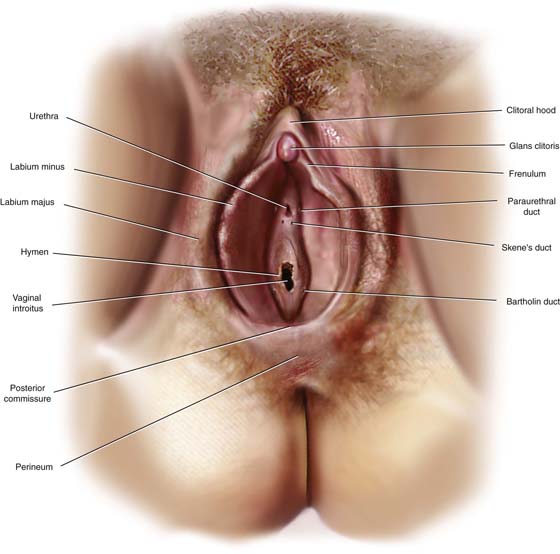

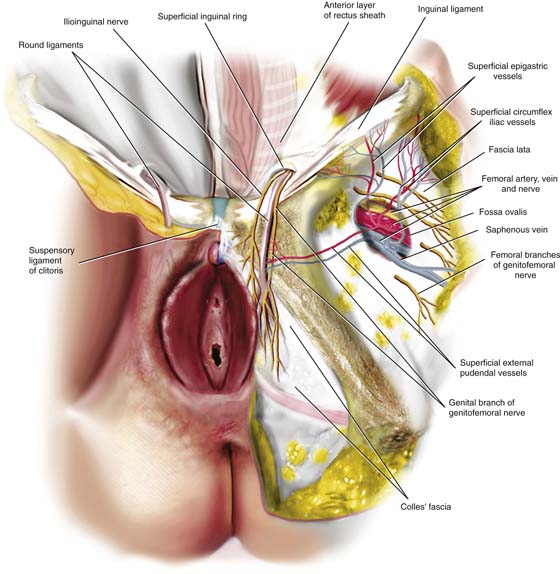

The vulva consists of the labia majora, labia minora, vestibule, clitoral and periclitoral tissues, and perineum (Fig. 1–44). The greater vulva would include the mons veneris, crural tissues, and anal and perianal skin and structures. The vestibule contains many mucus-secreting glands and their ducts. The urethra and vagina also open into the vestibule. Beneath the vulvar skin is fatty subcutaneous tissue. The general contour of the vulva is largely created by fat and the deeper, Colles’ fascia. The round ligaments and the vestigial canal of Nuck insert into the deep layers of fat within the labium majus.

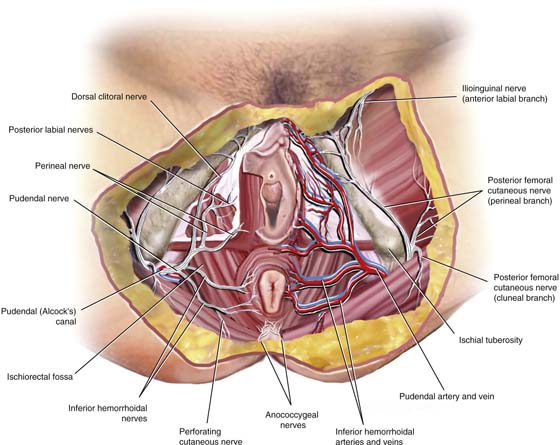

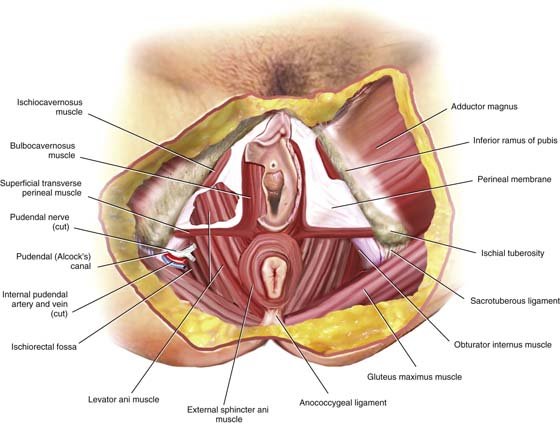

The pudendal vessels and nerves are found within the deep fat. The neurovascular bundle emerges just medial to the ischial tuberosity on either side. Branches are given off to the anus and lower rectum, perianal skin, vulvar skin, and superficial and deep vulvar structures (Fig. 1–45). When Colles’ fascia is peeled away, the muscular structures of the vulva are exposed. These consist of the external (and internal) sphincter ani, the superficial transverse perineal muscle, the ischiocavernosus muscle, and the bulbocavernosus muscle. Bridging the space between the latter three muscles stretches a tough fascial sheet, the perineal membrane. When the perineal membrane is opened, the underlying levator ani muscle is exposed. The dissector should note the topographic relationships by locating the ischial tubers and the pubic arch, and by inserting a finger into the rectum and vagina (Fig. 1–46).

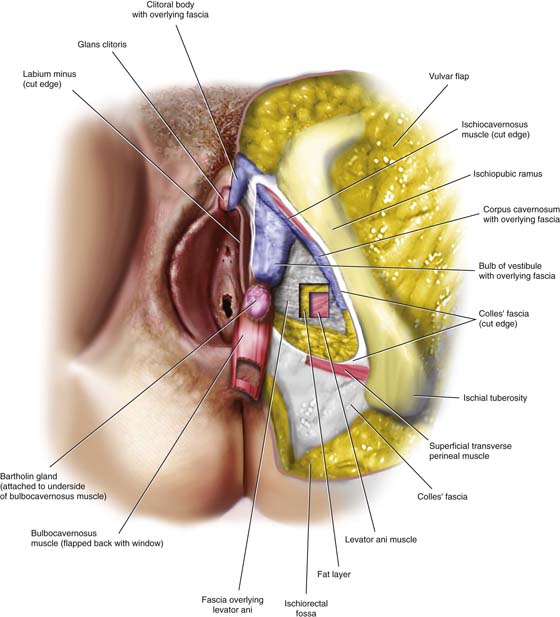

By careful dissection, the perineal muscles are separated from the underlying structures. The deep perineal cavernous apparatus is brought into view (Fig. 1–47). This consists of the bulb of the vestibule, corpora cavernosa clitoris, clitoris body, and glans clitoris. Lying on the underbelly of the bulbocavernosus muscle and attached to the vestibular bulb is the Bartholin gland. Deep to the space located between the perineal muscles is the levator ani muscle. It is curious that, in both fixed and fresh cadaver dissections, the “perineal body” cannot be found. The muscle directly beneath the perineal skin and fat is the external sphincter ani.

The femoral triangle, although part of the thigh, is closely linked to the anatomy of the vulva directly and to gynecologic reconstructive surgery indirectly. The muscles of the thigh were discussed and illustrated earlier (see Figs. 1–14 and 1–15). The great saphenous vein lies within the fat on the medial aspect of the thigh. Dissection of that large vein cranially will lead the anatomist to an oval depression filled with meshlike connective tissue (cribriform fascia) and the fossa ovalis (Fig. 1–48). The saphenous vein empties into the large femoral vein, which is itself encased in a very tough fascial compartment. Immediately lateral to the femoral vein, likewise within its own fascial compartment, is the femoral artery, and lateral to it, the femoral nerve. Three small vessels emanating from the femoral vein (or saphenous) and femoral artery may be identified by careful dissection. These are the superficial external pudendal, the superficial epigastric, and the superficial circumflex iliac vessels. Medial to the femoral vein is the femoral canal, whose medial boundary lies against the lacunar ligament.

The round ligament encased in transversalis fascia and accompanied by the genital branch of the genital femoral nerve, as well as the ilioinguinal nerve, spills over the pubic bone superficial to Colles’ fascia. It inserts deeply within the fat of the labium majus (see Fig. 1–48).

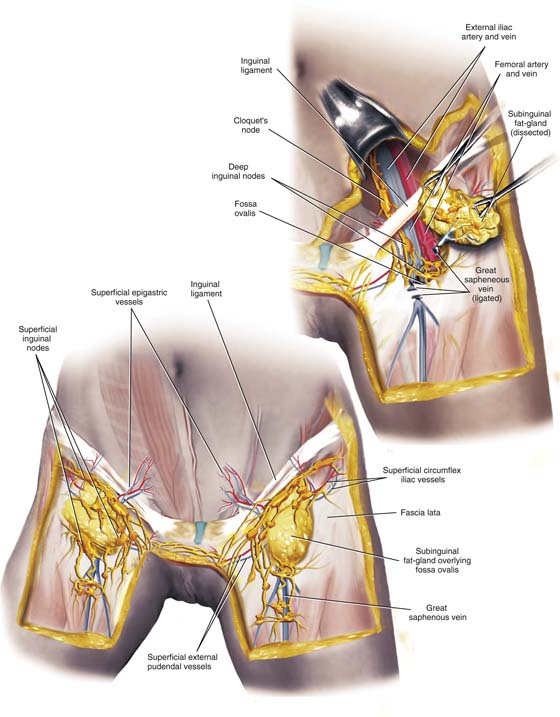

The lymphatics of the vulva drain to the thigh (groin) via lymph vessels first to the superficial inguinal and secondarily to the deep inguinal lymph nodes (femoral nodes). The former (superficial) are associated with the three superficial vessels described earlier, as well as the saphenous vein, and lie within the fat of the thigh (Fig. 1–49).

The deep inguinal (femoral) lymph nodes lie along the femoral vein and femoral canal. They drain into the external iliac nodes. The lowest of the external iliac nodes lies in the femoral canal and is known as Cloquet’s node.

The vulvar lymphatics cross over from right to left and vice versa within the fat of the mons veneris; therefore, contralateral as well as ipsilateral lesions may drain to the groin nodes on any given side.

The relationships of the major vessels, nerves, lacunar, inguinal ligament, iliopsoas, and pectineus muscles, as well as the pubic bone, are illustrated in Figure 1–50.

In summation, the surgeon must have a precise and thorough knowledge of pelvic anatomy and specifically of the relationship of one structure to neighboring structures at every location within the pelvis. This knowledge is particularly vital when distortion is encountered because of adhesion formation. The basic anatomy is preserved within the underlying retroperitoneum.

FIGURE 1–43 This sagittal view illustrates the drainage of the upper cervix (above the blue divisional line) into the hypogastric nodes, as well as the lower cervix draining into the lateral sacral nodes. (After Meig’s Surgical Treatment of Cancer of the Cervix, 1954, Grune and Stratton, p. 91, with permission.)

FIGURE 1–44 The greater vulva consists of the external genitalia, the mons, the crura, the perineum, and the perianal skin. Mucous glands derived from endoderm are located around the vaginal introitus and the external urethral meatus and consist of the Bartholin glands/ducts and the paraurethral glands/ducts. The area of the posterior fourchette and fossa navicularis is studded with minor vestibular (mucous) glands.

FIGURE 1–45 Pudendal nerves and internal pudendal vessels emerge from Alcock’s canal just medial to the ischial tuberosity. Branches pierce the fascia covering the muscles and can be found with the perineal fat. Colles’ fascia has largely been stripped away in this drawing.

FIGURE 1–46 The muscles forming the pelvic floor are shown here. The crural area is prominently seen and felt by the adductor longus muscle. The bulbocavernosus muscle is immediately lateral to the outer wall of the vagina. The ischiocavernosus lies along the margin of the pubic ramus. Between these muscles is a tough connective tissue structure called the perineal membrane. Blending into and deep to the bulbocavernosus muscle and external sphincter ani muscle is the levator ani muscle. Between the levator ani and the ramus of the ischium is the obturator internus muscle.

FIGURE 1–47 This picture shows the bulbocavernosus muscle turned down. Clinging to its inferior margin is the Bartholin gland. The bulb of the vestibule is exposed beneath the upper portion of the muscle. Beneath the ischiocavernosus muscle is the corpus cavernosa clitoris. The two corpora (right and left) unite at the lowest margin of the symphysis pubis to form the body of the clitoris. Essentially, these cavernous structures form a virtual blood lake.

FIGURE 1–48 The round ligament exits through the superficial inguinal ring accompanied by the ilioinguinal nerve and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve. These structures are buried in the fat of the mons and upper labium majus.

The fossa ovalis lies within the deeper layer of fat within the thigh. Three small blood vessels branch from the femoral artery and flow into the femoral vein. They include (1) the superficial external pudendal vessels, (2) the superficial epigastric vessels, and (3) the superficial circumflex iliac vessels. Lateral to the femoral artery is the femoral nerve. The large vein winding upward in the medial thigh fat is the saphenous vein.

FIGURE 1–49 The vulvar lymphatics drain first to the superficial groin (i.e., inguinal lymph nodes that are arranged in the cribriform fascia overlying the fossa ovalis and along the three superficial vessels noted in Fig. 1–48). Additional lymph nodes are located along the great saphenous vein, as are accessory saphenous tributaries.

The secondary inguinal lymph nodes consist of the femoral (deep inguinal) nodes, which are located mainly around the femoral vein and in the femoral canal. These in turn drain into the external iliac chain. The lowest of the external iliac (deep pelvic) lymph nodes lies at the top of the femoral canal and is known as Cloquet’s node.

The lymphatic channels of the vulva drain ipsilaterally and contralaterally with the crossover channels located in the fat of the mons venous.

FIGURE 1–50 This frontal view of the right hemipelvis shows, from medial to lateral, the femoral canal, Cloquet’s lymph node, the femoral vein, the femoral artery, the femoral nerve, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. These major structures lie on the pectineus and iliopsoas muscles.