1. Introduction to law

Learning objectives

• identifying the sources of the law

• understanding the different types of law

• identifying the features of the Australian legal system

• differentiating between criminal and civil law

• explaining the operation of the doctrine of precedent

• describing how to find and read a case citation

• understanding how to read an Act (also called a statute).

Introduction

Medical services are, to a significant extent, regulated and controlled by the law and the legal system. For example, a medical student is required by law to fulfil the educational and practical components of a medical degree before seeking registration to practice. Once registered as a medical practitioner it will be necessary to consider the relevant legal principles and issues prior to making clinical decisions about care and treatment of patients and clients. The provision of healthcare by medical practitioners, as with any other health professional, is therefore based on a framework of legal principles and legislative provisions which regulate and determine the standard of care to be delivered and the rights and obligations of both the providers and the recipients of the care. This area of law, which has come to be referred to as health law or medical law, operates to control not only what medical practitioners and healthcare institutions are expected to do, but also what they are to refrain from doing as part of their professional practice in the provision of their services.

An understanding of health law is fundamental to the provision of safe and competent medical care to a patient or client and, as such, exists as a resource for professional decision-making. Within the Australian context, health law refers to a wide variety of legal concepts. These include the common law, civil and criminal law, contract law, the regulation of industrial relations and agreements as well as the statutory arrangements between state and federal governments and Australia’s commitment to international treaties.

As health law is one subject area of the law that governs the conduct of medical practitioners, it is important to have an understanding of the Australian legal system and the language and terminology relevant to legal processes and structures. The purpose of this chapter is therefore to provide you with a broad outline of the structure and features of the Australian legal system, including the hierarchy of the courts, the impact of the doctrine of precedent and the sources of the law, so as to assist in an understanding of the content of the following chapters.

Where does the Law Come From?

The Australian legal system, as it currently exists, developed from both the historical links with Britain as a colonial power and the federation of the colonies. Each colony had developed independently and came together as the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901. Initially the British imposed their laws and system of government on the individual colonies. Despite the fact that each of the colonies had developed its own constitution by the end of the 1890s, it was considered desirable that they federate under one constitution. The Commonwealth Constitution Act 1900 (UK), passed by the British Parliament, effectively transformed each of the colonies into separate states federated under the name of the Commonwealth of Australia.

In Australia, there are two sources of the law:

1 The first is legislation passed by the parliaments at both the state and federal levels. Each of the state parliaments, through their individual constitutions, may pass laws for the ‘peace, welfare and good government’ of the state. 1 In addition, the federal parliament may pass legislation as specifically determined by the Commonwealth Constitution.

2 The second source is the law which has developed from decisions of judges handed down by the courts. This is also referred to as ‘common law’.

As the laws emanate from the state, territory and federal parliaments and the courts it is necessary that medical practitioners have an understanding of the laws that control and regulate the practice. Refer to Table 1.1.

| Judge-made or common law

• Judges decide on cases brought before the courts.

• Court proceedings are initiated by litigants (the parties to the proceedings) who have a dispute needing a legal remedy.

• Judges develop common law principle known as precedents.

• Cases are decided on the evidence presented and also within the parameters of established precedent or prior judgments.

• Judges apply legal remedies to actual disputes between people, or about points of law including equitable principles.

• The ratio decidendi is the reason for deciding or the principle of law upon which the case was decided.

• The judgment may contain comments that clarify a situation but do not make new law (obiter dictum). Comments made in obiter are not regarded as new law.

Legislation or statutory law (also referred to as an Act) • Legislation passed by parliament on a matter is known as a statute or Act (primary legislation).

• Statutory bodies and ministers have the power to make regulations and rules (delegated legislation).

• Legislation can apply to specific groups, individuals or context, or to the whole population.

• Judges may be asked to interpret the meaning of certain sections of legislation or regulations should a dispute arise in response to the application of the legislation.

|

Australia is often referred to as a common law country. This means that the system of government and courts are, in the main, similar to those of other common law countries, for example, the United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand. These countries also have both common law (from the courts) and statutory law (from the parliament) embodied in their legal systems.

Parliamentary law

One of the functions of a parliament is to enact legislation, also known as Acts or statutes, which are designed to regulate certain aspects of society. An Act of Parliament is considered to be the primary source of the law. This means that the law contained in the Act has priority over the common law (judicial decisions from the courts). Some states or territories have Codes. Where a Code exists, it is intended to be a complete statement of law in that particular area; for example, the Criminal Code (WA) which is intended to operate independently of the case law. While parliament enacts the legislation, the role of the court is to interpret those sections of the legislation that are relevant to the cases before it.

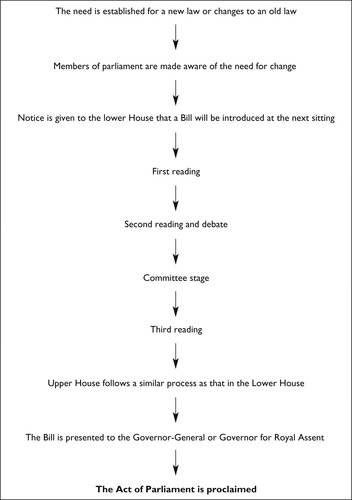

The state and federal parliaments consist of a lower house of representatives and an upper house of review. The exceptions are Queensland and the territories where there are no upper houses of parliament. There is an established procedure for the passage of legislation through both the state and federal parliaments. An item of legislation will be known as a ‘Bill’ prior to it being finally passed into law when it then becomes an Act. Refer to Figure 1.1.

|

| Figure 1.1 |

There are many Acts of Parliament at both the state and federal levels which regulate and control the practice of medical practitioners and the provision of medical services. To give some examples, at the state level, there are statutes that set the standard of practice against which the conduct of medical practitioners will be compared in making a decision as to whether there has been a breach of the duty of care, legislation identifying substitute decision-makers when a patient lacks capacity to make their own healthcare decisions, legislation controlling workplace health and safety and legislation providing avenues for complaints by healthcare consumers about the care they have received from a medical practitioner. At the federal level, the legislation may address issues such as funding and regulating Commonwealth healthcare agencies and services.

The law at the state and federal level is also impacted upon by Australia’s international obligations. International law is a body of rules that regulate and control the conduct of nations in their dealings with one another in an international context. These general principles of international conduct are variously called treaties, protocols or declarations and are negotiated by members of the United Nations. When the Commonwealth government is a signatory to an international treaty, it must pass domestic legislation that is consistent with the obligations of that particular treaty. Therefore, the influence of international treaties and conventions on Australian domestic law is becoming increasingly significant. For example, the language of the mental health legislation in each of the states and territories draws heavily on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the laws in relation to children reflect the obligations imposed under the Declaration of the Rights of the Child (Article 4) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 24). Australia is a signatory to these documents.

The process of enacting an Act (statute)

While a law is progressing through parliament, it is referred to as a Bill. Once passed by parliament and assented to by the Governor-General, it becomes an Act of Parliament. The process involved in the passing of an Act entails the following of certain procedures in a prescribed sequence as shown in Figure 1.1.

The first stage is when members of parliament are given notice that at the next sitting of parliament a Bill will be introduced. Explanatory documents and a brief outline of the reasons for the Bill usually, but not always, accompany this announcement. The Bill is then placed on the agenda for the next parliamentary sitting. Unless the Bill pertains to a matter of urgency, it is not dealt with in detail at that sitting other than by way of a reading of the long title. This is known as the first reading and generally the whole Bill is not read. Ministers are given the documents to take away and read in preparation for the next stage. If the matter is urgent then standing orders will be suspended and the Bill will be debated and passed that day. Such a situation occurred in New South Wales in 1984 when the Minister for Health was given power to close public hospitals without prior consultation with the public or officers of the Department of Health. As a result, and despite public outcry, Crown Street Women’s Hospital in Sydney was closed the following day.

Under ordinary circumstances, the Bill is debated at a later date. This is referred to as the second reading. At that time the matter is debated and the parties in opposition may propose amendments before the Bill is passed by the lower house.

At the committee stage, each of the provisions of the Bill will be debated with the full house of parliament sitting as a committee. This stage of the process is a procedural mechanism and does not require the members of the parliament to operate as an investigative committee. The purpose is to consider the details of a Bill after the second reading and examine any amendments proposed by the upper house if it is referred back. Basically this process is a way of determining whether any of the provisions in the Bill fail to meet the intention of the proposed law, or if there are any unintended consequences arising from any sections of the Bill. The Bill then moves on to a third reading and is passed by the lower house. In situations where the government has an overwhelming majority in the house, it is possible that the Bill can be forced through all of these processes and emerge without undergoing the scrutiny that would be insisted upon if the numbers of government and opposition were more balanced.

The Bill is then referred to the upper house where it is examined and debated in a manner and sequence similar to that of the lower house. Any amendments to the Bill recommended by the upper house are referred back to the lower house and if these are accepted, the Bill is presented to the Governor-General or Governor for Royal Assent. Once this occurs the Bill becomes an Act of Parliament. The Act may not become effective immediately as it must be proclaimed. Sometimes the proclamation date will be mentioned in the Act, but usually it will be at a date to be fixed. One reason for this delay is to enable the executive government or bureaucracy to establish the necessary mechanisms for implementing the Act. Rarely will an Act be set up to take effect retrospectively.

Regulations

One of the last sections in an Act confers on the Governor-General the power to make regulations that may be necessary for the administration of the Act. Regulations provide the essential details of administration that may change more frequently than the Act can be amended by parliament. Regulations are necessary to enable the daily implementation of the Act. The regulations are called delegated legislation. Regulations are usually drafted in the Attorney-General’s Department, advised by the department responsible for administering the Act. Though the regulations are tabled in parliament they do not progress through parliament in exactly the same manner as a Bill.

Statutory interpretation

Statutes and regulations determine much of the professional activity in the delivery of healthcare. For example, the respective civil liability legislation in each of the states and territories identifies the standard of care for health professionals; the legislation and regulations controlling drugs and poisons set out the requirements for the storage, possession and administration of drugs and poisons; and the guardianship legislation provides for a substitute decision-maker for those patients and clients who have no capacity to make healthcare decisions. Legislative provisions pertaining to the health industry are therefore regularly amended and updated.

When reading legislation and regulations the focus must be on the actual words used. Examples of words that compel include will, must or shall whereas words such as may are discretionary. The first step in interpreting the legislation is to read the statute as a whole so that the context of the words can be identified. Words that have a simple meaning can take on a technical or special meaning in legislation. Explanatory notes sometimes accompany the statute and associated regulations, to help resolve ambiguity or emphasise the intention of the law. The interpretation of statutes is now governed by various commonwealth, state and territory Interpretation Acts2 that enshrine the common law rules regarding interpretation of legislation.

Legislation may be accessed via hard copy or ‘online’ via the world wide web (www) or other dedicated databases generated and maintained by Commonwealth, state and territory governments. In addition to the individual government websites, 3 all Australian legislation can be found at www.austlii.edu.au. 4 The format of the legislation in hard copy will differ from that available online however, the following aims to provide a general overview to assist in reading an Act.

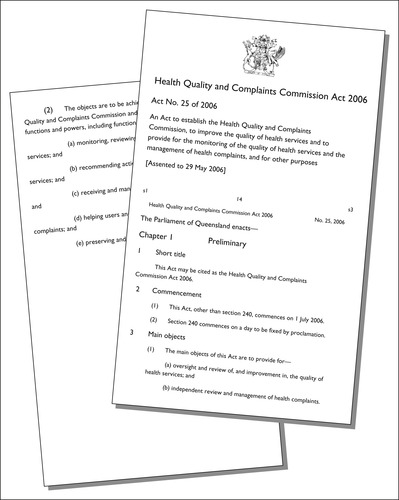

The coat of arms of the particular jurisdiction usually appears at the top of the front page of an Act. All Acts are given a number; for example, the Health Quality and Complaints Commission Act 2006 (Qld) is Act No 25 of 2006. Numbering is strictly in the order in which the Acts are assented to by the Governor-General. 5 If the date of assent is included it usually appears in brackets under the long title (see Figure 1.2 Reading an Act); this is the date on which a Bill formally completes its passage through the parliament and meets the constitutional requirements for becoming an Act. It is not necessarily the date on which the Act comes into effect (see Commencement in Figure 1.2).

|

| Figure 1.2 |

The layout of an Act depends on its subject matter. Many Acts are divided into chapters and/or parts, which are like chapters in a book. For example, the Health Quality and Complaints Commission Act 2006 (Qld) has 241 sections in 17 chapters. Within many of the chapters are parts, which are broken down further into divisions. For example, ‘Chapter 1— Preliminary’ is comprised of sections 1 to 10 and contains items such as the short title, the commencement, main objectives, who is bound by the Act, the dictionary and meanings of ‘health service’, ‘provider’, and ‘user’. Certain items and prescribed forms are more conveniently set out in a list appended to an Act. This is achieved in the form of a schedule. Sections in the Act will refer to a schedule and this has the effect of incorporating it into the law. The schedules in the Health Quality and Complaints Commission Act 2006 (Qld) identify facilities and institutions that are declared to be, or declared not to be, health services, relevant registration boards, amendments to other Acts consequential to the operation of this Act, and a dictionary of terms.

Delegated legislation

An Act as passed by parliament may provide that a particular person or body, for example a Minister of the Crown, the Governor-General or professional regulatory authority, is delegated the power to make rules, regulations, by-laws or ordinances in relation to specified matters. For example, section 101 of the Healthcare Complaints Act 1993 (NSW), empowers the Governor, under the Act to:

(1) …make regulations, not inconsistent with this Act, for or with respect to any matter that by this Act is required or permitted to be prescribed or that is necessary or convenient to be prescribed for carrying out or giving effect to this Act.

(2) The regulation may create an offence punishable by a penalty not exceeding 20 penalty units.

Although this delegated power is derived from the Act and does not exist in its own right, such rules, regulations, by-laws and ordinances are binding and are to be read as one with the Act. A regulation made under the delegated power is inherently more detailed and precise in its practical application than what is provided in the Act. It is of note that in relation to the management of drugs and poisons, it is often the regulations that state the individual practitioner’s obligations in prescribing and administering the substances.

Common law

The common law is the accumulated body of law made by judges as a result of decisions in cases that come before the courts. Since the Norman Conquest in the 11th century the decisions handed down by judges have been applied in similar cases that came before them. The recording of cases and the principles established in the decisions provided a level of certainty in the operation of the law (refer to the doctrine of precedent below). These decisions can be located in the law reports of the jurisdiction where the case was decided.

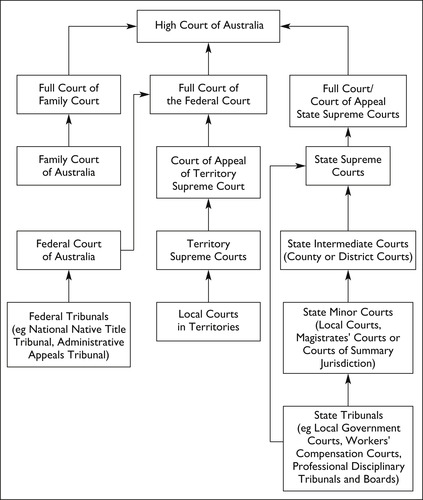

Australia inherited the common law at the time of British settlement. However, since that time, both prior to and following federation, the Australian legal system has continued to develop a large body of judge-made law. Generally, statute law overrides common law and common law prevails when no specific statute exists. Both common law and statute law are applied in the courts. In Australia, there is a hierarchy of courts (refer to Figure 1.3) within the state and territory jurisdictions and the federal jurisdiction.

|

| Figure 1.3 |

One feature of the common law is the development of equitable principles. These principles were developed by the English Court of Chancery. Equitable principles have evolved to address the issues of fairness and justice in those cases where common law remedies were considered to be inadequate. The rules of equity prevail over inconsistent common law rules. An example of an equitable maxim is ‘He who comes to equity must come with clean hands’. That is, where parties are seeking an equitable remedy, they themselves must have behaved in an honest, fair and lawful manner.

The Court Hierarchy

The Australian court system is structured hierarchically so as to delineate the extent of authority and the jurisdictional limits of each court (refer to Figure 1.3). The word jurisdiction refers to the authority, or power, vested in a court of law allowing it to adjudicate or decide on an action, suit, petition or application brought before it. Jurisdictional power varies according to the seriousness of the offence, the amount of compensation that can be awarded, the nationality or place of residence of the parties, whether the matters are criminal or civil in nature, or even when and where the offence or event occurred. For example, a charge of unsatisfactory professional conduct bought against a medical practitioner will be heard initially by a disciplinary tribunal such as the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal. This tribunal has, under the relevant legislation, the jurisdiction, or power, to make a finding of guilt or innocence and, if necessary, make an order if the medical practitioner is found guilty. There is no such jurisdiction or power under the legislation for the District or Supreme Court to hear the charge or make an order. Another example is a claim by a patient alleging negligence against a medical practitioner which would be heard in a civil court. If a medical practitioner were charged with murder, manslaughter or criminal negligence in relation to the death of their patient this trial would be conducted in a criminal court. Clearly courts such as the Family, Maritime or Environmental Courts would have no power (jurisdiction) to hear such matters, award damages or pass sentence should the plaintiff or prosecution succeed.

Original and appellate jurisdiction

When a matter first appears, the court in which it is heard has what is known as original jurisdiction. Before a decision may be appealed in another court, the dissatisfied party must be able to establish appropriate grounds. In this case, the subsequent court will be exercising its appellate jurisdiction. A decision may be the subject of an appeal in certain circumstances, including when a judge has misdirected a jury, made an error in relation to admitting or refusing to admit evidence, or there is an issue as to the severity or leniency of the sentence. For example, the Supreme Court may hear a matter and if its decision is appealed, then the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court will hear the following case using its appellate jurisdiction, where appropriate. Appellate jurisdiction is restricted to the superior courts including the District/County Court, Supreme Court, Federal Court, Family Court and High Court. In relation to the High Court, special leave (permission) must be sought before it will exercise its appellate jurisdiction. An overview of the court hierarchy follows, to illustrate the differences in both structure and jurisdiction of the courts in the hierarchy. Refer to Figure 1.3.

Overview of the courts/tribunals

Magistrates’ Courts or Local Courts are presided over by magistrates who are addressed during the proceedings as ‘Your Worship’, or in some jurisdictions as ‘Your Honour’. Magistrates sit alone as there are no juries at this level in the court structure. The jurisdiction of the Magistrates’ Courts is determined by the relevant legislation in each of the states and territories. These courts are the lowest courts in the hierarchy and determine the greatest volume of cases. As a general principle, Magistrates’ Courts deal with minor civil and criminal matters and with more serious criminal matters by way of committal proceedings. For example, a medical practitioner may appear before a magistrate in relation to practising without a licence or being in possession of property they have unlawfully removed from the premises of the employing institution. It is from this level of the hierarchy that magistrates are appointed as coroners or to preside over Children’s Courts and Licensing Courts. These courts developed in response to the need to reduce the load from the Magistrates’ Courts and in recognition of the requirement for specialist knowledge. Coroners’ Courts are of particular relevance to medical practitioners. It is in the Coroners’ Courts that an inquiry will be conducted to establish the identity, the time, circumstances and/or cause of a patient’s death. The jurisdiction of a coroner to conduct an inquiry into the death of a person is determined by the legislation in each of the individual states and territories.

Coroners’ Courts are presided over by a coroner who is, as indicated above, a magistrate. The significance of the coroner lies in their power, inherent in the relevant legislation, to hold public hearings on ‘reportable’ deaths’ (referred to as a Coroner’s Inquest) in which the public issues can be investigated and considered. In Australia a coroner will usually be assisted in the inquest by the expertise of specialist investigators such as police, scientists, forensic pathologists, aviation investigators, navigation investigators and medical specialists. The role and function of the Coroner’s Court, and the coroner, is established by the legislation in each state and territory. 7 The principal role of the coroner is to investigate deaths that are unexpected, unnatural, accidental or violent. These are called ‘reportable deaths’ and must be reported to the coroner. The legislation in each of the states and territories identifies the meaning of a ‘reportable death’ and the jurisdiction of the coroner. Generally, a ‘reportable death’ will include not only as stated above, one that is unexpected, unnatural and/or violent, but also a suspicious death, a death that occurs following an operation, an anaesthetic, a medical, surgical, dental, diagnostic or health related procedure, or when a person dies in custody or in care. As the requirements differ between the individual jurisdictions, a medical student or medical practitioner must familiarise themselves with the legal provisions applicable in the state or territory in which they are practising. In addition, the role of the coroner is to determine whether there are public health or safety issues arising from the death and whether there is any action that is required in order to prevent deaths occurring in similar circumstances. A feature of this court is that it is designed to be inquisitorial rather than adversarial. The coroner is not bound by the rules of evidence and may conduct an inquiry in any manner which facilitates the inquisitorial nature of the proceedings.

District or County Courts are presided over by judges who sit with or without a jury. Their jurisdiction is both original and appellate. District Courts hear and determine civil and criminal matters that are governed by the relevant legislation in each of the states and territories. As a general statement, all criminal matters other than murder, manslaughter, serious drug matters and serious sexual assault will be heard in the District or County Court. The judges who preside in these courts and more senior courts are referred to as ‘Your Honour’.

Supreme Courts are the most senior courts in the states and territories and are presided over by a judge, with or without a jury. Supreme Courts have an internal appeal mechanism referred to as the Full Court of the Supreme Court. When the court is sitting as the Full Court, there are three or more judges. While the jurisdictional limitations are determined by the relevant legislation in each of the states and territories, in civil matters the court may hear claims for unlimited damages and in the criminal jurisdiction for murder, manslaughter, serious drug matters and serious sexual assault. It is in the Supreme Court that most medical negligence cases involving medical practitioners will be conducted.

The High Court was established under the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia and is comprised of the Chief Justice and six other judges. The first High Court was appointed under the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). Historically, the Privy Council in England was the final Court of Appeal for State Supreme Courts and the High Court of Australia. The right to appeal to the Privy Council was abolished progressively between the 1960s and the 1980s. While the High Court is the most senior court in the Australian hierarchy, it is possible for a case to be heard by an international court or tribunal. This can occur if federal parliament has become a signatory under an international declaration or convention.

The original jurisdiction of the High Court concerns any matters that involve interpretation of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia, or disputes between residents of different states, or between states and the Commonwealth government.

Provided permission (referred to as ‘leave’) has been obtained, appeals to the High Court of Australia can come from the Federal Court, the Family Court and the Supreme Court of any state or territory involving civil or criminal matters. The full bench of the High Court, comprising all seven justices, hears cases in which the principles are of major public importance, involve interpretation of the Constitution or invite departure from a previous decision of the High Court. Appeals from state and territory Supreme Court decisions, and from decisions of the Family Court, will be dealt with by the full court of not less than two justices. A single justice may hear and determine specified matters. You will note in the following chapters that a number of the cases in relation to actions taken against medical practitioners have progressed on appeal from the state or territory courts to the High Court of Australia for determination.

The Federal Court of Australia was established under the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). This court was set up to further reduce the load on the High Court. Constitutional cases involving such matters as trade practices, bankruptcy and federal industrial disputes are heard. Appeals on decisions can be made to the High Court or the Full Court of the Federal Court.

The Federal Magistrates’ Court was established in 2000 to deal with less complex matters than would otherwise have been heard in the Federal or Family Courts. The range of cases coming before the Federal Magistrates’ Court include matters relating to bankruptcy, discrimination, privacy and family law. This court does not hear appeals.

Specialist tribunals may be established under Commonwealth or state laws to exercise specific jurisdiction and perform functions similar to that of the courts. The number and type of tribunals are increasing as government regulation of society becomes more complicated. Tribunals are established by statutes for different purposes and therefore their powers and composition vary greatly. Examples of tribunals include administrative appeals tribunals, tenancy tribunals, small claims tribunals and professional regulatory tribunals. These tribunals perform ‘quasi judicial’ functions in that they make decisions within the ambit of their limited or specific roles. Decisions are made in a variety of ways and may involve a judge or, alternatively, a board of specialists who may, or may not, be qualified in law. Unlike the courts, the tribunals do not make laws that are applied by the courts. In a number of Australian states and territories the individual specialist tribunals have been amalgamated into multi jurisdictional tribunals. The ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal (ACAT), Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal (QCAT), Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT), and the Western Australian State Administrative Tribunal (SAT) include an extensive range of jurisdictions. In New South Wales the Administrative Decisions Tribunal (ADT) deals with administrative appeals and particular civil matters while the Consumer, Trade and Tenancy Tribunal deals with commercial, consumer and tenancy disputes. Although tribunals lie outside the court hierarchy, appeals may be made from their decisions into the court system, if permitted under legislation. Often the role of tribunals is limited and narrowly defined.

The Doctrine of Precedent (Stare Decisis)

In the discussion of common law, mention was made of the role of judges in making law. The word ‘common’ is used to denote the fact that judges have developed a process whereby courts are, to a certain extent, bound to follow decisions they have made previously as well as being bound by decisions made by other judges at the same level of the hierarchy or in senior courts. Judge-made law, or common law, began as a custom that valued the accumulation of judicial wisdom passed on through the ages. In this way, a common thread of judicial certainty was maintained despite different judges presiding. Early in the 19th century, this custom became enshrined as a doctrine known as stare decisis or the doctrine of precedent. It allows for some predictability when dealing with legal matters involving courts because one is able to determine the outcomes of similar cases that have occurred before, and estimate the probability of similar judgments being passed.

The doctrine of precedent originated in England and over time developed into a sophisticated and historically consistent system of justice. The underlying principle is that if a case is decided in a certain way today then a similar case should be decided in the same way tomorrow. The reason or ground of a judicial decision is called the ratio decidendi. It is the ratio decidendi of a case which makes the decision a precedent in future cases. When the courts hand down their decisions, they are to be found in the many law reports that emanate from the state, federal and international jurisdictions. It is important to remember that many cases are not included in the published law reports; however, unreported decisions should be equally regarded as establishing precedent.

All judgments do not bind all courts. Nor are all judges compelled to follow all that has been set down in previous decisions. Precedent can only bind if it comes from a higher court within the same hierarchy. For example, a decision in the Supreme Court of NSW is binding upon the District Court in NSW and Local Courts in NSW but it is not binding on the equivalent courts in other states and territories of Australia because they are not in the same court hierarchy. Even so, a lower court in one state or territory would be unlikely to depart from a decision taken in a higher court of another Australian state or territory where the issues are similar.

Australian laws apply only to Australian courts. Australian courts are not bound to follow decisions made in foreign courts; however, they can influence decisions taken in Australia. This is sometimes referred to as persuasive precedent. For example, decisions made in other common law countries such as Canada or the United Kingdom may be considered by the Australian courts. Judgments made in English courts are no longer binding on any Australian court.

Case references

It is important for medical practitioners to understand decisions from the courts as contained in the various law reports. The following will provide an overview of the elements of a case reference to assist you in reading and understanding cases. For example, in the case of Harriton v Stephens (2006) 226 CLR 52 means:

• Harriton v Stephens refers to the parties involved in the case. If it is the first time the case has come to court the first party named is the plaintiff and the second party is the defendant. If the case is on appeal then the first party will be the appellant and the second party the respondent. It is usual form to italicise the names of both litigants.

• (2006) refers to the year the case was reported. When the year is in round brackets it indicates that the volume number, and not the year, is the essential identifying feature of the citation. When the year is in square brackets it indicates that the year is the important identifying feature of the report and that the volume number is not essential, and may not even be present. An example is [1975] VR 1. When more than one volume is published in a particular year the volumes in that year will be numbered.

• 226 refers to the volume number of the law report.

• CLR is the abbreviation for the Commonwealth Law Reports series containing the report on the case of Harriton v Stephens.

• 52 refers to the page reference for the beginning of the case report. Commonly used law reports are listed in the abbreviations section of the appendices.

Law reports

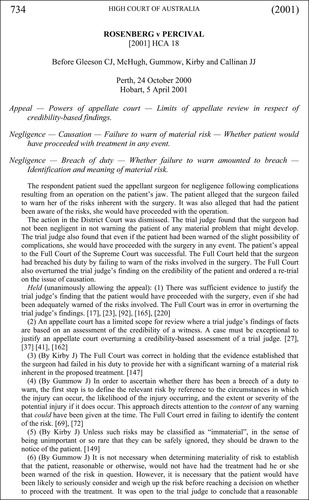

For medical practitioners to understand the common law principles that apply to their practice, it is necessary to have the skills to read a reported case. The following will provide an overview of the features of the case of Rosenberg v Percival (2001) 74 ALJR 734 (refer to Figure 1.4).

|

| Figure 1.4 |

As this is an appeal to the High Court, Rosenberg is the appellant and Percival is the respondent. The letter ‘v’ between the names of the parties is the abbreviation of the Latin word versus and signifies that the parties are against one another in the adversarial process of litigation. Directly beneath the names of the parties is the court in which the case was decided, in this instance the High Court of Australia. Below the court title are the names of the justices before whom the case was heard, being the Chief Justice, Mr Anthony Gleeson, and Justices McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Callinan.

As this is an appeal, the last court that decided the case is referred to next; in this case it was the Supreme Court of Western Australia. Directly below are words or phrases that are written in italics. These are the catchwords considered to be the important aspects of the case. Catchwords in this case include:

… Negligence — Breach of duty — Whether failure to warn amounted to breach — Identification and meaning of material risk.

The next section is referred to as the ‘headnote’ which is a summary of the case. These are the facts of the case which the reporter, responsible for providing the ‘headnote’ to the publisher, considered important to that decision. It is essential therefore to have a comprehensive understanding of the case by reading the entire judgment. The actual decision of the court, indicated by the word ‘Held’ contains the ratio decidendi. A summary of the findings of each of the judges who heard and determined the case is also provided. This may appear as separate reasons as delivered by each of the justices or, where there is agreement (where they concur), two or more justices may hand down a joint decision. At the end of the written determination the ‘orders’ (the judges’ final decision) handed down by the court will be reported.

Cases may also be found ‘online’ via the world wide web (www) or on CD-ROM or disc. 4 The increase in cases able to be accumulated through storage on the electronic databases has resulted in unreported cases (those not formally reported in the printed volumes of the law reports) now being available. As an example, though the unreported case of Edwards v Kennedy is not available in the reported cases it is able to be located via LexisNexis, AustLII or a number of other legal databases. It is to be noted that the format of case reports on web-based and online databases differs from that of the traditional paper-based law reports in that there are no volumes or page numbers in the report, and the paragraphs are individually numbered for reference. As an example, the unreported case Edwards v Kennedy, a case involving allegations of medical negligence, is reported on the LexisNexis data base as:

Edwards v Kennedy BC 200901404,

Supreme Court of Victoria – Common Law Division

Kaye J

5714 of 2007

26,27 February, 12 March 2009

Citation: Edwards v Kennedy [2009] VSC 74

There are various methods of classifying the different types of law, one method being to describe law as either substantive or procedural.

Substantive law is the law that regulates citizens in specific areas of their lives. This includes industrial law, contract law, criminal law, family law, tort law and even constitutional law. Procedural law governs the way in which laws are implemented and enforced. This would include rules of the courts, rules applied to civil and criminal procedures and rules of evidence. An understanding of the different types of law will assist with identification of the differences, similarities and effects of both the substantive and procedural law. Both common law (the decisions of judges in cases before the courts) and parliamentary law (Acts of state and Federal parliaments) combine to produce substantive law. The list below is not exhaustive but refers mainly to those areas of law that impact on the practice of medical practitioners.

Some examples of substantive law include the following.

• Industrial law where matters arising from the employer and employee relationship are identified and defined. Primarily industrial law involves agreements and awards that establish the obligations and rights of both parties in their working environment.

• Contract law which places agreements within a formal framework that enables promises made by the parties to be enforced. Medical practitioners come into contact with a range of contractual agreements, including contracts of employment, contracts between a specialist medical practitioner and their patients and contracts for the purchase and sale of goods and services.

• Criminal law identifies activities which the state considers unacceptable to a degree that warrants punishment. Criminal law may apply in the healthcare setting in relation to grossly unacceptable conduct or behaviour such as theft, criminal assault, manslaughter or murder.

• Tort law is concerned with civil wrongs. The word ‘tort’ essentially means ‘twisted’ and was interpreted as amounting to conduct which was ‘wrong’. The primary purpose of tort law is to redress the wrongs suffered by a plaintiff. This is accomplished by the provision of compensation which seek to put the injured party in the position they would have been in, had they not suffered the damage. There is rarely an element of punishment; however, one of the functions of tort law is to act as a deterrent by regulating behaviour to an acceptable standard. In the healthcare context, examples of tort law include negligence, negligent misrepresentation and trespass to the person.

• Constitutional law sets out the legal framework within which the country’s political and legal systems operate.

Procedural law involves the processes of litigation, controlling the actions of all parties involved prior to trial and then regulating the way the trial will proceed. This aspect of law is the machinery that allows substantive law to be processed and applied. For example, it will determine: the legal rules governing evidence that can be presented in court; how a case progresses through court; and the requirements of proof.

Another significant distinction of the law is that between civil and criminal law. Table 1.2 sets out the common distinguishing features that differentiate civil from criminal jurisdictions.

| Features | Civil | Criminal |

|---|---|---|

| Who brings the legal action. | The legal action involves one citizen, for example a patient, bringing an action against another citizen (who could also be a corporation such as a hospital or healthcare facility). | The legal action is initiated by the state (represented by the public prosecutor or the police) against an individual or institution (the defendant) who has allegedly committed the crime. |

| The standard required to prove. | On the balance of probabilities. | Beyond reasonable doubt. |

| The outcome sought in a civil action. | Financial compensation. | Punishment through imprisonment or fine. |

General Features of The Australian Legal System

Adversarial system

The function of the law is to resolve disputes when there are conflicts between individuals, companies or institutions. This takes place in a court when a case is brought before a magistrate, judge, or judge and jury, and the parties are adversaries to one another and only one of the parties will be declared the ‘winner’. This competition between the parties takes place within the courts and is referred to as the adversarial process. The role of the judge during court proceedings is to remain impartial and to ensure that the procedural rules are adhered to. The judge or jury will determine the outcome where only one of the parties to the proceedings will be successful.

This adversarial process is different from the inquisitorial approach where the court is effectively inquiring into a set of circumstances and may thereby become a participant in the actual process. That is, the court is not confined to the evidence put before it by the police and lawyers, but may seek out information in its own right as part of the process of reaching a decision. Within the healthcare context, the operation of the Coroner’s Court in investigating the cause, time, and location of a death as described earlier would be classified as inquisitorial. Cases involving negligent actions, for example a patient suing a medical practitioner in negligence, will progress in an adversarial manner.

Natural justice

In a general sense, the notion of natural justice ensures that the proceedings are conducted fairly, impartially and without prejudice. Natural justice is a fundamental principle that applies to all courts and tribunals. It means that the court or tribunal must give the person against whom the accusations are made a clear statement of the actual charge, adequate time to prepare an argument or submission, and the right to be heard on all allegations. It is described as making two demands:

before a person’s legal rights are adversely affected, or their ‘legitimate expectations’ disappointed: (1) an opportunity to show why adverse action should not be taken…; and (2) a decision-maker whose mind is open to persuasion, or free from bias. 8

Presumption of innocence

The law regards all accused people as being innocent until proven guilty. This is a core principle of the Australian legal system. As an example, in a criminal matter the presumption is that the accused is innocent until proven guilty. In civil proceedings, the presumption operates so as not to allocate liability until all of the elements of the action are proven.

Mediation

In all Australian jurisdictions, Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) is used in the civil jurisdiction as a mechanism to assist the parties, either before or after the commencement of legal proceedings, to negotiate and resolve their dispute. Mediation has become one of the more popular methods of ADR and is defined as ‘a process … under which the parties use a mediator to help them resolve their dispute by negotiated agreement without adjudication’. 9 Whether mediation is the appropriate mode for the attempted resolution of a dispute will be determined on a case-by-case basis, however, in many jurisdictions both the legislation or court may refer proceedings to mediation whether or not the parties object. 10 It has been suggested the objective of ADR in legal proceedings is ‘to assist the parties to reach a negotiated and satisfactory resolution of their dispute, improve access to justice and reduce the cost of delay’. 11

SCENARIO AND ACTIVITIES

A medical practitioner working in general practice fails to order appropriate tests for a patient they have been treating for the past year. The patient continues to attend the practice, complaining of the same signs and symptoms, however, the medical practitioner ignores the complaints and tells the patient to take Panadol and rest. The patient dies suddenly and it is discovered on autopsy that the patient had a large malignant tumour which caused a rupture of the aorta and sudden death. The patient’s family is now commencing legal proceedings against the medical practitioner, seeking damages for their father upon whom they were all financially dependent.

• What action do you think the family would initiate against the medical practitioner?

• In what court would such an action be conducted?

• What other courts or tribunals may be involved given the facts of this scenario?

To ensure you have identified and understood the key points of this chapter please answer the following questions.

1 What are the sources of law in the Australian legal system?

2 Identify some Acts of Parliament (state, territory and Commonwealth/federal) that will regulate and control your practice as a medical practitioner.

3 Describe how you would identify a professional obligation that was required on the basis of the delegation of power from an Act.

4 What is the significance of the doctrine of precedent to negligence cases involving a breach of the duty of care by a medical practitioner?

5 How does the legal concept of natural justice operate?

6 Describe the difference between an adversarial and an inquisitorial process. Identify the legal proceedings in which the parties are adversaries and a legal process in which an inquiry would be undertaken.

8 Identify the courts in the court hierarchy from the lower court to the most senior court. Where are tribunals located in relation to the court structures?

9 Please go onto the website www.austlii.edu.au or attend the law library in your university and locate one of the following health-related cases. Identify the court in which the proceedings are being conducted, the parties to the proceedings (the litigants), the health-related legal issues and the outcome.

(a) Harriton v Stephens (2006) 226 CLR 52.

(b) Hunter Area Health Service & Anor v Presland [2005] NSWCA 33.

(c) Gardner; re BWV [2003] VSC 173.

10 What are the features that distinguish a civil from a criminal action?

Further reading

In: (Editor: Butt, P.) Butterworths Concise Australian Legal Dictionary3rd ed (2004) Butterworths, Sydney.

Carvan, J., Understanding the Australian Legal System. 5th ed (2005) Law Book Co, Sydney.

Chisholm, R.; Nettheim, G., Understanding Law. 6th ed (2002) Butterworths, Sydney.

Cook, C., Laying Down the Law. 6th ed (2009) LexisNexis, Sydney.

Hall, K.; Macken, C., Legislation and Statutory Interpretation. 2nd ed (2009) LexisNexis Butterworths, Sydney.

Hanks, P., Australian Constitutional Law. 5th ed (1997) Butterworths, Sydney.

In: (Editor: Heilbronn, GN) Introducing the Law7th ed (2008) CCH Australia, Sydney.

Hinchy, R., The Australian Legal System: History. (2008) Institutions and Method, Pearson Education, Sydney.

Wallace, M., Healthcare and the Law. 3rd ed (2001) Law Book Co, Sydney.

Waller, L., Derham, Maher and Waller: An Introduction to Law. 8th ed (2000) LBC Information Services, Sydney.

Zines, L., The High Court and the Constitution. 4th ed (1996) Butterworths, Sydney.

Endnotes

1.

2.

3.

4.

5. Acts of Parliament: A reader’s guide. (1992) Parliament House, Canberra; (brochure).

6. Morris, G.; Cook, C.; Creyke, R.; Geddes, R., Laying Down the Law. 5th ed (2001) Butterworths, Sydney.

7.

8. Forbes, J.R.S., Justice in Tribunals. 2nd ed (2006) Federation Press, Sydney; at 100.

9.

10

11 Cairns, B.C., ‘A review of some innovations in Queensland Civil Procedure’. Aust Bar Rev. 26 (2005) ; 158–161.